So already we can see that ~$140,000 is not some mythical number that is unattainable by American families. For the type of family Mr. Green is interested in, half of the families are already at this income level. True, that does mean that half are also below it, but the $80,000 figure he keeps using as a baseline isn’t anywhere near the right number. When he says things like “If one parent stays home, the income drops to $40,000 or $50,000” (from the supposed $80,000 baseline), he is drastically understating the financial situation of a typical family.

Green also mistakenly ignored a crucial part of American families’ real and growing wealth—their homes—because they’d have to sell the asset to realize any substantial price appreciation. (“[I]f the home you live in goes from $200,000 to $1,000,000, you are not wealthy,” Green writes.) But, as Boehm notes, that’s a “crazy leap”: Beyond the fact that Americans frequently tap their home equity for myriad reasons, they can and often do simply sell and move to a lower-cost place or property, banking real money in return. You can’t just write that off.

Second, Green wildly overstated what the average American must spend to support a family and meet basic needs. He claimed the $140,000 that U.S. households need was “conservative, national-average data.” But after a little digging, Horpedahl found that Green came to this number using cost-of-living data from Essex County, New Jersey—one of America’s most expensive regions. After Green admitted the error, he suggested Lynchburg, Virginia, as more nationally representative, but this change alone dropped his personal threshold for American “poverty” to $93,755—46 percent lower than the original, viral claim.

As Horpedahl further explained, this error resulted in Green using certain cost figures that were downright absurd. Most notably, the centerpiece for his argument about struggling two-earner households was data from the MIT Living Wage Calculator (LWC) showing an annual two-child child care expense of $32,773. But that, again, was in Essex County. In Lynchburg and similar areas, by contrast, child care costs were just $12,544—meaning Green’s figure was a comical 161 percent too high. As Cowen and Boehm add, even a correct child care cost figure wouldn’t have saved Green’s estimates because he applied those costs to all years of parenthood, even though families pay them in just the first few. (As any parent can tell you, child care expenses shrink to nothing as kids get older.)

Green also made other cost errors (only, it seems, in the pessimistic direction). Winship explains, for example, that Green’s kooky methodology for calculating a minimum American food budget misread the poverty analysis on which it was based, and thus overstated the number significantly. The LWC, on which the local cost figures were derived, also has problems. And Green’s broader inflation adjustments were flawed (something that tends to happen a lot with these viral analyses), again resulting in significantly inflated family costs.

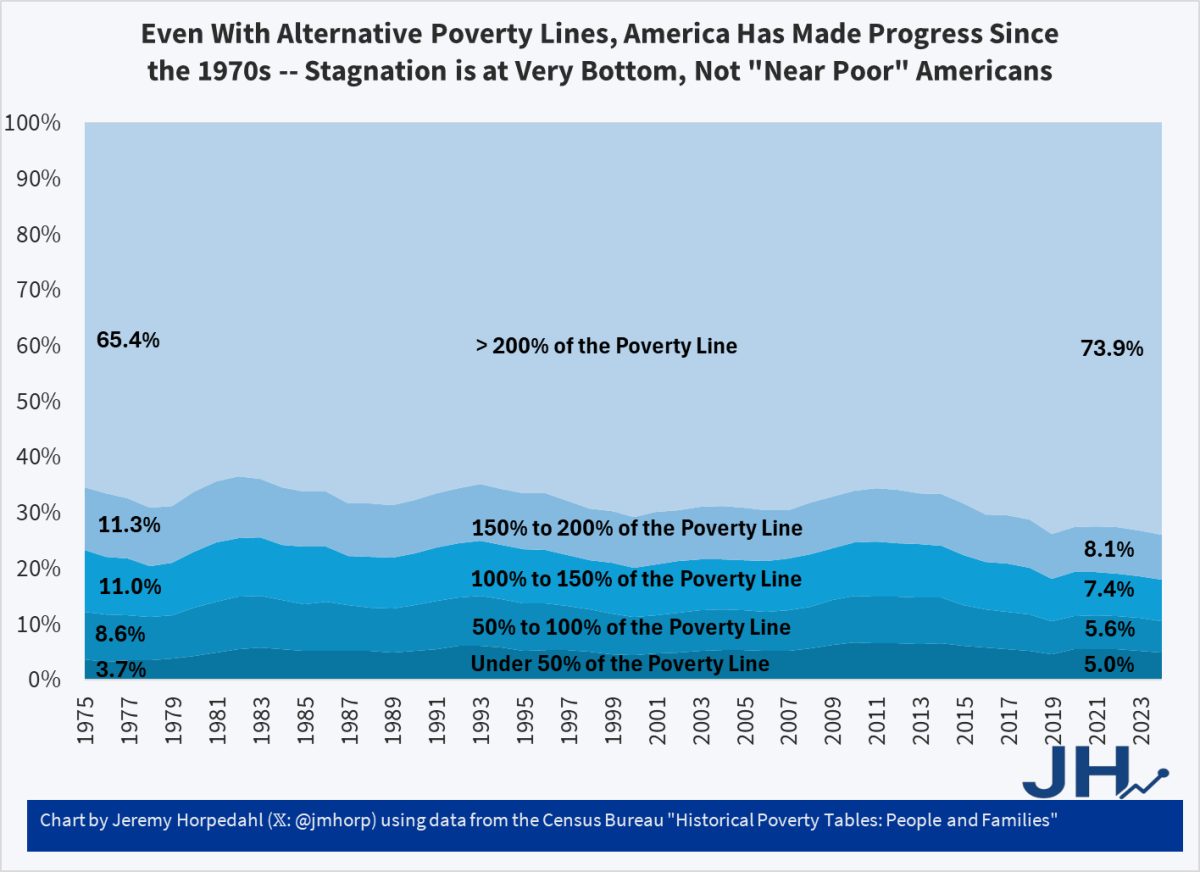

Third, while Green is correct that the official poverty measure is subjective and flawed, he ignored existing and superior poverty analyses. For example, Horpedahl notes, the Census Bureau’s supplemental poverty measure (SPM) already accounts for food, housing, clothing, and utilities, and it makes geographic adjustments for regional cost disparities. Yet its poverty thresholds range from just $35,000 in Little Rock to $60,000 in costly San Jose, and—just as importantly—it tells a pretty optimistic story: Using the SPM consistently over time, American poverty fell from 13 percent in 1980 to 6.1 percent in 2023. Horpedahl adds that the Census Bureau has other poverty metrics, and these too reveal slow progress—not doom and gloom:

Winship, meanwhile, shows similarly optimistic trends in serious, non-government efforts to better calculate American poverty:

The most comprehensive effort to address these issues is a recent paper by Richard Burkhauser, Kevin Corinth, James Elwell, and Jeff Larrimore (ungated version here). These authors use a complete after-tax income measure, set the poverty line so that 19.5 percent of the population is poor (as the [Official Poverty Measure] does), and update that threshold for inflation with a better price index than the OPM uses. They find that poverty fell to 1.6 percent by 2019—much lower than the decline to 10.5 percent found by the OPM. … The authors of the paper also show results setting the 2019 poverty rate to 10.5 percent and then looking back at what the 1963 rate was using this more generous threshold. The answer is that the poverty rate was 70 percent. Either way, poverty has fallen dramatically.

As Winship has documented elsewhere, other measures of cost-adjusted American incomes also show progress. Real earnings for the typical year-round male worker, for example, have increased 46 percent from 1973 to 2023 (accounting for inflation, taxes, and benefits), while the increase was an astonishing 121 percent for women. And contra the antiglobalization narrative, “earnings growth among young men has been stronger during the past 35 years than in the previous 15.”

Finally, and more fundamentally, Green erred badly when redefining “poverty” to mean something much different from what it’s always (and importantly) meant: a person’s inability to meet basic needs—food, shelter, clothing, and so on. Green instead defines “poverty” as difficulty affording what he calls “participation tickets” for modern middle-class life, including two cars, market-rate child care, and comfortable housing in desirable neighborhoods. As Boehm explains, however, defining “poverty” as being able to afford a median American lifestyle is ridiculous:

Like in fictional towns where all the children are above average, this simply doesn’t make sense. Not every family will be able to afford the median apartment; that’s what makes it the median apartment. And while it is certainly true that even relatively wealthy people can feel financially stretched at times, that’s hardly the same thing as being in poverty.

As he further details, defining poverty in this way can cause us to categorize Americans with $1 million homes or just one car as being poor, regardless of their actual wealth, living standards, and life choices. Real poverty conjures images of hunger, homelessness, and deprivation, but Green applies it to the mundane middle-class experience of having a monthly budget and facing everyday trade-offs between competing goods and services. A family earning $120,000 per year and having to choose between saving more for retirement and taking a nicer vacation is not experiencing “poverty.” They’re experiencing the universal human condition of finite resources meeting infinite wants. Yes, that condition can be annoying at times, but it ain’t poverty.

When we examine what actual poverty looks like, we see a relatively small share of Americans suffering today. Beyond the official figures that Winship and Horpedahl cite, for example, Noah Smith points out that just 10 percent of American families with children experience food insecurity at any point during a year, while only 14 percent of American children live in overcrowded housing (defined as more than one person per room). Just 8 percent of Americans lack health insurance, and more than 80 percent of four-person households own two or more cars. Americans have also experienced substantial improvements in both caloric consumption and living space, and we overwhelmingly possess all the genuine necessities. Could things be even better? Sure. But these figures are still a long, long way from Green’s estimate that most American households are living in “poverty.”

In the end, Green’s critics pushed him to retreat from his original allegation—the one that went viral—to a policy issue that’s real but also far more mundane: how federal “welfare cliffs” can punish American families for earning more because they’ll lose eligibility for various government benefits. As Horpedahl’s analysis shows, this can indeed be a problem: A hypothetical Lynchburg family, for example, would see almost no increase in net resources as its market income rises from $45,000 to $63,000, because federal benefits phase out in this range. But the issue is neither new nor as serious as Green claims. Organizations like AEI and Cato (and others) have long advocated for welfare reforms that would minimize or eliminate these cliffs, but they affect a relatively small share of the U.S. population. In short, reform is needed, but this a long way from Green’s initial assertion that vast swaths of the American middle class are today living in “poverty.”

Prosperity Remains a Tough Sell

That millions of people approvingly shared Green’s original analysis still raises the question of why Americans enjoying reasonably comfortable lives and historically high incomes still appear to feel so “poor.”

I think some of it is, as we’ve already discussed, psychological. Humans’ innate “hedonic treadmill” causes us to adapt quickly to real-but-subtle improvements in our living standards, so we can take for granted things that would’ve seemed miraculous to previous generations. A 2025 middle-class family enjoys better and cheaper essentials—housing, transportation, communications, medicine, consumer goods, technology, and more—than what families earning much higher incomes had in the 1960s. But these advances disappear into the background of our everyday lives while new wants—a bigger house, a nicer car, more exotic vacations—enter the foreground of our thoughts.

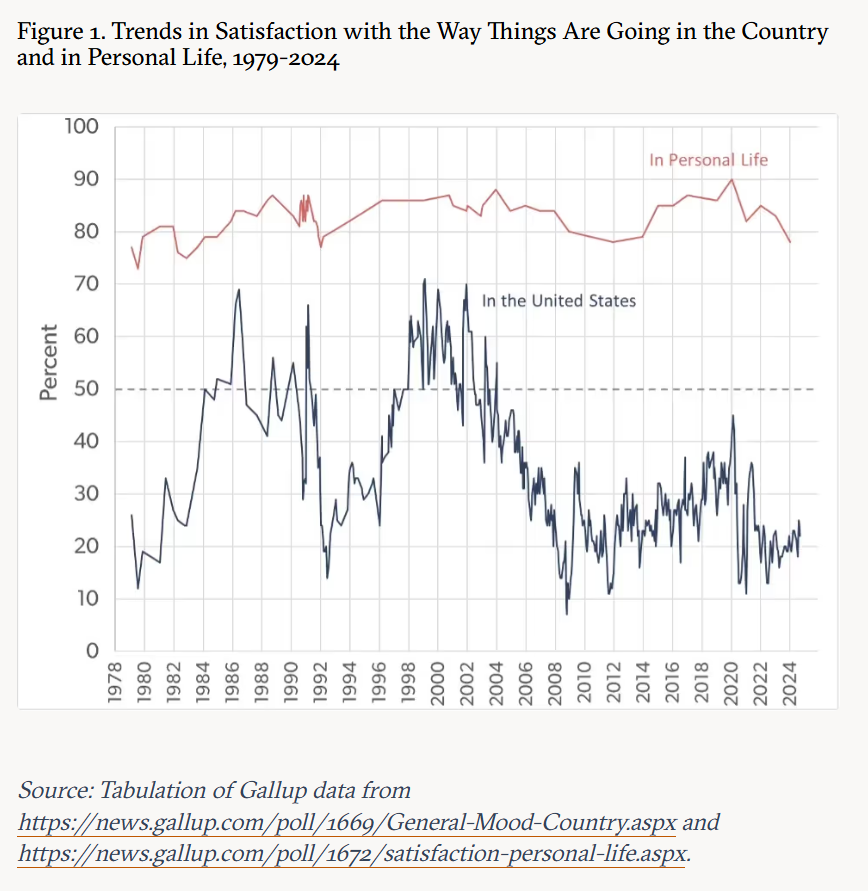

This isn’t ingratitude; it’s biology. And it’s amplified by nostalgia (especially as our society gets grayer), modern communications technology (the internet, cable news, etc.), and the many suppliers of economic doom who profit from our innate lack of contentment. Saying we live in an era of unprecedented material abundance also can come off as minimizing real struggles. It’s easier to embrace narratives of broad-based societal decline, even as we also consistently acknowledge that our own situation is pretty much fine:

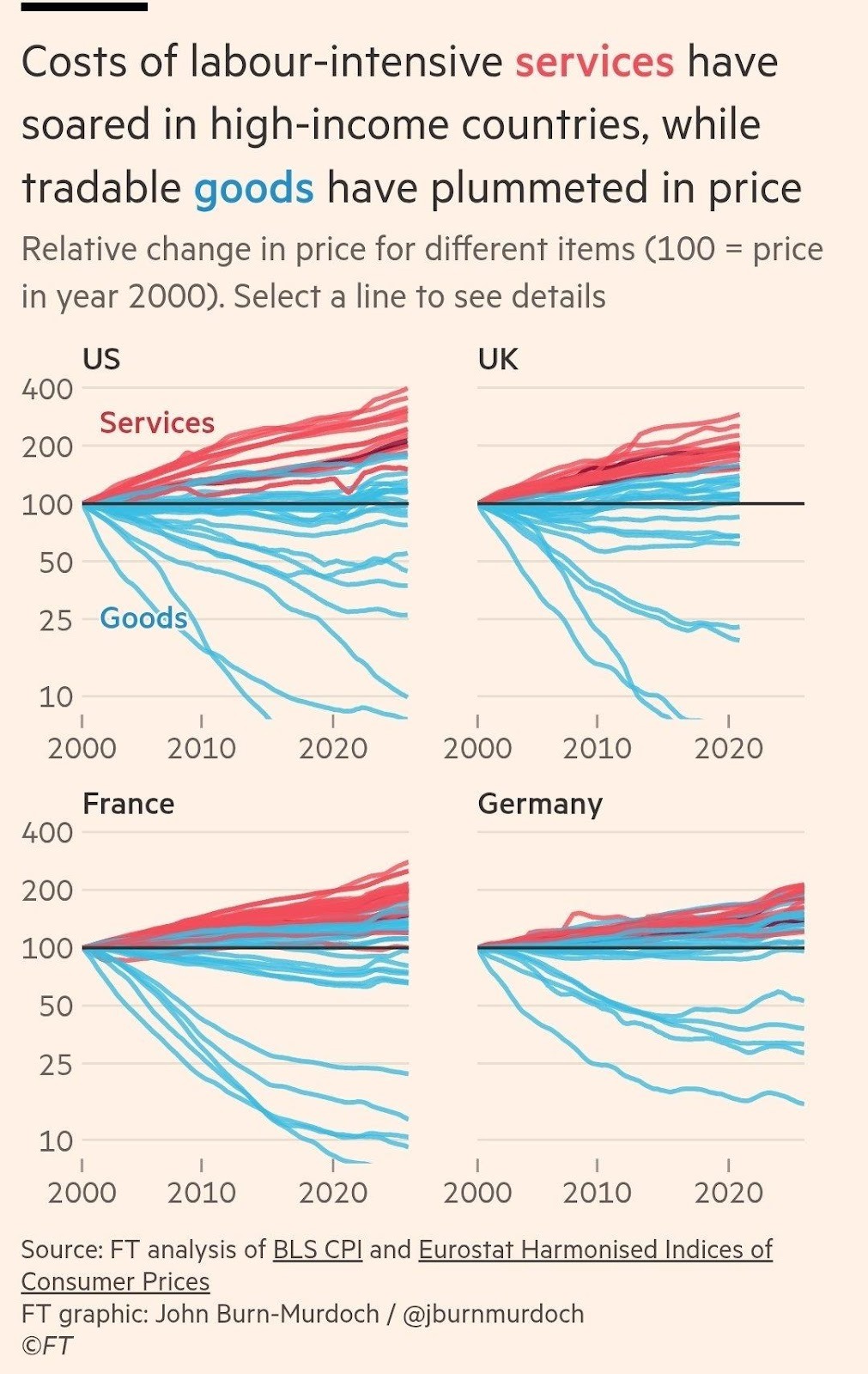

Psychology isn’t, however, the only thing at play here. Economics plays a role too— in particular, the phenomenon known as Baumol’s cost disease. As the Financial Times’ John-Burns Murdoch just detailed, Americans’ overall cost of living has improved over time, but certain highly visible and socially desirable services have become more expensive. That’s not a conspiracy against the middle class but instead just Baumol at work:

[A]s countries develop economically, the same productivity growth that drives down the cost of tradeable goods causes the cost of in-person services to balloon. Wages in sectors like healthcare and education that require intensive face-to-face labour, and have slow (if any) productivity growth, are forced upwards in order to attract workers who would otherwise opt for high-paying work in more productive sectors. The result is that even if people keep consuming the exact same basket of goods and services, as living standards in their country increase they will find more and more of their spending is going on essential services.

Sectors where productivity grows slowly and prices outpace inflation—health care, education, child care, personal services, housing (construction), etc.—happen to be the same ones that middle-class families notice most and that signal social status. As we’ve all gotten richer, moreover, these services have transitioned from luxuries to expectations. Throw in the hedonic treadmill and the fact that you can’t price-shop schools or hospitals the way you can TVs, and public alarm is all but inevitable. Surely, Baumol isn’t the only thing going on in these industries (more on that in a sec), but that it’s happening across the developed world is a strong sign it’s a powerful driver:

Finally, there’s just the good ol’ economic reality that trade-offs in life are unavoidable no matter how wealthy we become. As Reason’s Boehm noted, for example, having children is expensive and requires choices and sacrifices, but we do it because it’s rewarding in other ways. The trade-offs, in other words, are worth it. Others might prefer to make a different choice—to buy a nicer home or to maintain a more upscale lifestyle—but those choices come with trade-offs too. It’s inescapable. And it’s certainly not a sign of “poverty.”

Perhaps the most important trade-offs in this regard, Matthew Yglesias explains, relate to household structure and families’ choice between having two full-time earners or having one earner and one full-time homemaker. As he details, the “tradlife” model is still possible today but requires economic sacrifices—a smaller house, a different neighborhood, public schools, etc.—that many Americans don’t actually want to make when presented the two-earner alternative:

What’s gone up is not the cost of living relative to a single earner’s wages, but the opportunity cost of the second adult not working. Nothing is stopping a typical married American couple from accepting 1960s material conditions in exchange for one parent being a full-time homemaker. It’s just that most people don’t want that…. To actually not work and instead spend more time on non-market production, you’d need to accept a lower income. But two-adult, middle-class American households are incredibly affluent by global and historical standards, and most of them absolutely could do this if they wanted to.

Put another way, dual-income families are the norm in America not because one income became inadequate, but because female workforce participation—a gradual trend that started many decades ago and actually peaked in the 1990s—created opportunities most families have chosen to pursue. Yes, this choice came with trade-offs (new child care and transportation costs, less family time, etc.), but it also increased household incomes, expanded women’s economic opportunities (and, in most cases, their happiness, too), and boosted household wealth and living standards. Some Americans choose to forgo those things and embrace the one-earner tradlife, and that’s totally okay. But many, if not most, want the affluence that two earners provide, and that’s okay too.

A problem arises only when Americans expect to enjoy today’s standard, two-earner consumption bundle with yesterday’s standard, one-earner income. (See Winship’s latest on housing as a great example.) That’s comparing economic apples and oranges, and it likely fuels a lot of today’s online angst about American families struggling to get by.

Summing It All Up

The most frustrating part of the Great $140,000 Poverty Debate isn’t the wrongness or virality of Green’s analysis or even his conspiratorial online ad hominems. It’s that the hysteria obscures some of the very real affordability challenges families face today and the many legitimate policy reforms that could help to ease these burdens. Trade-offs are real and Baumol is too, but there are still lots of ways we could improve Americans’ access to housing, education, child care, health care, household necessities, and more. My book Empowering the New American Worker details dozens of such reforms, and many other proposals come from serious institutions across the political spectrum.

Our work gets harder, however, when the debate is hijacked by viral claims redefining prosperity as “poverty” and throwing most of the country into the latter camp. Government interventions for actual poverty can differ greatly from policies addressing middle-class cost pressures, and targeting the former—with broad-based cash transfers, for example—can actually make the latter wors, not better. Productive reform also becomes more difficult when voters and policymakers believe the entire system is irredeemably broken, requiring not targeted fixes but wholesale replacement. Overall, it’s a very bad way to do policy—even if it feels true.

Chart(s) of the Week