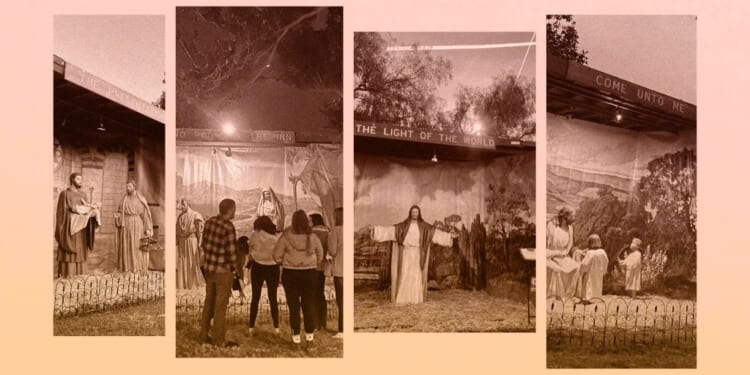

The sacred and the mundane meet in the middle of the main drag of my adopted hometown outside Los Angeles each Christmas season. From just before Thanksgiving to just after New Year’s, a dozen scenes depicting the Nativity and life of Christ hold their ground in the wide, parklike center median of Euclid Avenue running through downtown Ontario, California. Crafted by a Hollywood hand whose true calling was religious art, the tableaus seem to appear out of nowhere each year unless you happen across the set-up crews at work.

In truth, there’s a saga behind the scenes, and the crèches have endured the region’s ripping Santa Ana winds, several years of constitutional contention, at least one car crash, and countless pranks and heists. “Ontario Looking for Jesus,” read the local newspaper headline after the 2005 theft of a 6-foot-tall Christ statue.

The wise men outlasted the wise guys, though, and for nearly seven decades the scenes have been faithfully repaired, reassembled, and displayed for all to see every Advent. The survival and enduring appeal of these displays of faith offer hope for those of us who believe Christianity should have a place in the public square and not be confined to the most private realms. But it would be a mistake to interpret the Nativity scenes’ story as some sort of culture-war triumph. In our current societal context, the existence of these tableaus is more countercultural and out of the ordinary than an overbearing imposition from the dominant religion.

I’ve come to find these scenes a reassuring and steadying presence in my year-end life, pointers to deeper meaning in this season. The hard question in our cultural and political moment is whether the themes of humility, mystery, and God-with-us conveyed in these displays can get through when, far beyond this one boulevard, Christianity in America is at a confounding crossroads. On the one hand, the role of religion has been declining in many Americans’ lives. Concurrently, a significant segment of Christians are asserting a cultural-political vision of the faith that focuses on attaining earthly power. From a Christian vantage point, there is not much to be gained if Nativity scenes like this are simply quaint markers of a fading cultural heritage or empty symbols embraced by politics-first Christians who have lost the message the symbols are meant to convey.

We are at a strange place. Christians, at least of one stripe, have access to power under the Trump presidency perhaps like never before in modern times. Court cases weighing the Free Exercise and Establishment clauses of the Constitution have been shifting in a positive direction for religious expression for years now. Much has been made of the New Theism, with even atheists and agnostics acknowledging the positive contributions Christian ways of thinking have made in forming the cultural and moral underpinnings of the Western world.

But in another sense, the influence of many Christian ideals appears to be in a freefall. In current GOP politics, we hear so much talk about upholding Christianity, but the accompanying public discourse leaves little room forJesus’ teachings: turning the other cheek, going the extra mile, doing unto others as you would have them do unto you. Self-sacrificial love, at the center of Christ’s message, is tough to find in a political vision based on retribution and retaliation. It’s not only a MAGA mindset: Here in blue California, it was unsettling to hear supporters deploy the rhetoric of “fighting fire with fire” in pushing through a skewed redistricting plan in response to Texas’ skewed redistricting plan.

This takes us a long way from the tableaus lining Euclid Avenue. Can these scenes and their story point us to a different path? If you stay on the sidewalks that line either side of the avenue, with Corollas and Civics whizzing past angels and shepherds, it’s tough to absorb the story depicted on the other side of the pavement. But if you venture out into the grassy center, especially when the sun sets and the street lights glow overhead, the median feels set apart, a place to roam and ponder.

Over time, I’ve watched a diverse assortment of people, in groups, as families or on their own mini-pilgrimages, make their way from scene to scene as Christmas draws near. Kids sometimes run rings around the displays, or even rush up and touch the statues. Adults are typically reverent when they encounter the crèches. I see their seeking as a hopeful sign. We need a wider space for this type of open wandering and pondering.

Perhaps public expressions of faith were built into Christian practice from the early days as much for the benefit of the individual believer as for the larger audience: It’s hard for humans to hold onto an entirely personal, privatized faith. From this standpoint, the noncoercive presence of religious symbols like the crèches, even in a public roadway, can be seen as an intrinsic part of the free exercise of religion enshrined in the Constitution.

If you can get beyond the Christmas story’s familiarity, the displays present a picture of vulnerability and dislocation: no room at the inn, an infant in a manger, the hurried escape to Egypt. “Flight into Egypt,” a simple scene depicting Joseph, Mary, and an infant Jesus stopping to rest against a desert backdrop, is the scene I like to visit after dark in the stillness under the canopy of magnolia and California pepper trees. Beneath the branches, an old stone church with arched doorways and windows looms in the background. In the silence at night, when traffic is scant, there is always some light coming through the church windows. The Gospel passages embodied in the scenes like “Flight into Egypt” offer a different portrait of God’s son, as Garry Wills writes in his book What Jesus Meant, being “a fugitive, driven farther away from the familiar, the comfortable, into an exile that recalls the wandering of the whole Jewish people.” Will this picture sink in for myself and others?

The tableaus arrived on the scene at a time of dislocation: Ontario’s population more than doubled in the 1950s alone, and migrants from the Great Plains, Midwest, and other regions had been descending on the region for decades. During this period of rapid growth and change, a yuletide controversy erupted that’s a little hard to fathom in hindsight. For Christmas 1958, downtown merchants put together a carnival, complete with Ferris wheel and kiddie rides, to drum up business. The backlash was strong, with many seeing the carnival as too crass for Christmas.

Preachers, civic leaders, and service groups set out to do something more reverent to draw visitors for the years ahead, enlisting artist Rudolph Vargas, a talented sculptor and devout Catholic, to create a life-like series of Nativity scenes. An immigrant from Mexico, Vargas embodied the can-do ethos behind the project, often working for Hollywood (including helping to create statues for Disney amusement park attractions) by day to pay the bills, and pursuing his religious art when he could. The first pair of Ontario tableaus, a traditional manger scene and another depicting an angel appearing to shepherds, with statues formed from plaster and papier-mâché, was unveiled for Christmas 1959. Community and civic groups rallied the citizenry to fund more scenes, and Vargas kept them coming over the next decade until the full set of 12 was completed.

Trouble arrived in 1971 via a burnt-orange Buick Opel, whose driver initiated one of the earlier known attempts to swipe the statues (a recurrent issue), in this case ditching them after someone intervened, according to the police report. During this same time, a larger existential issue loomed in the background in the form of Supreme Court cases such as Lemon v. Kurtzman, which brought new tests and scrutiny for religion in the public square.

The controversies didn’t hit Ontario head-on until decades later in 1998, when cab driver Patrick Greene saw city workers helping set up the displays. His initial (and reasonable, in my view) objection to the involvement of government employees led the city to step back, handing off the work to the chamber of commerce and a cadre of community volunteers, who put in the work to keep the tradition alive. Still, a couple years of ever-more-complicated conflicts over the crèches followed. One dramatic moment arrived with a debate in a packed church between a local pastor and atheist Greene, who, sadly, was booed and heckled by some, as reported in the local paper. At another grim point, the state’s transportation agency decided that only four of the dozen scenes could stay before backing down under legal threat. Greene, in time, moved out of state. The crèches stayed.

Today, a nonprofit entity owns and cares for the historic scenes, and a Hollywood set decorator/prop stylist oversees restoration and maintenance of the statues.

Now the Nativity scenes seem firmly affixed on Euclid Avenue. But even as the national pendulum swings back to greater latitude for public religious expression, Americans’ faith practices are waning, with Gallup finding that “the U.S. increasingly stands as an outlier: less religious than much of the world, but still more devout than most of its economic peers.”

In the outlier realm, we could see an increasingly politics-and-power-oriented Christian subculture and the rest of the country increasingly put off by or disinterested in it. In a national sense, we could save the crèches and lose what matters. There’s danger in both apathetic acquiescence to secularism and miss-the-point power-seeking. But none of this is inevitable, as we learn in the surprising arc of the story of the Euclid Nativity scenes. Christianity has receded and revived in America before, and our current spiritual predicament needn’t be permanent. The faith’s future course in America may depend in part on whether Christians can find a fitting role in the public realm, to make an open invitation, without the goal of control.

With Christmas less than two weeks away, the tableaus are back up in downtown Ontario. All the Josephs and Marys and Jesuses are in their places, and plenty of people are walking along the median from display to display with kids in tow. Many more will visit the displays, not at flock-to-the-malls levels by any means, but enough to signal that the quest for deeper Christian ideals and Jesus’ story remains a presence in our public world. Despite the mishaps and at times messy human conflicts that have accompanied the tableau tradition, the fact that people value the Nativity scenes is one heartening signpost on what can be a busy, blurry path. In the view from Euclid Avenue, it’s hard not to keep some hope that American Christians may still make it past the extremes of both cultural passivity and power-seeking, trying to find that narrow road.