Both candidates who reached the second round promised to crack down on crime and immigration. Jara vowed to hire more police, build more prisons, secure borders with advanced technology, and deport foreigners convicted of drug trafficking. This message ultimately proved less persuasive coming from the left than the right—but Kast’s 16-point electoral margin yesterday overstates his personal popularity.

“You probably have 30 or 40 percent of the electorate center that is uncomfortable with either Kast or Jara,” Kenneth Roberts, a Cornell University government professor specializing in research on polarization and democracy in Latin America, told TMD. “It’s a pretty stark choice between a far-right candidate and a left-wing candidate, and so people who are in and around the center don’t really have anywhere to go, naturally. A lot of them are uncomfortable with either of those or ideological alternatives.”

Boric won his election four years ago after years of angry—and occasionally violent—protests in Santiago, Chile’s capital, over the cost of living and the quality of government services. Many voters were enraged by the country’s high student fees, private pension system, and struggling health care system, and Boric promised to be their champion—not just by enacting his agenda via legislation but by introducing an entirely new constitution to cement his policies.

This was not as radical as it might sound. Very few Chileans are pleased with the country’s current constitution, which was adopted in 1980—under the rule of dictator Augusto Pinochet, who controlled the country from 1973 to 1990—and has been amended about 60 times since. But Boric’s 54,000-word proposed replacement was a left-wing wish list that would have guaranteed Chileans the right to work, prohibited all forms of job insecurity, formed a new national health care system, banned for-profit schools, and legalized both abortion and assisted-suicide procedures. The “right to sports” was also inscribed, and the document recognized the rights of “nature” and animal sentience. It went to a referendum in September 2022—only six months into Boric’s term—and Chilean voters overwhelmingly rejected it.

Boric was still able to enact some of his agenda during his term—including raising the minimum wage and reducing the maximum number of weekly working hours from 45 to 40—but Chile’s congress blocked more ambitious measures, including a tax reform proposal in March 2023. In 2024, Boric told El País that he should not have “bet so much on the outcome of the first constitutional process—and having postponed important reforms based on it.” In October, a poll found that 61 percent of respondents disapproved “of how Boric conducts his government,” with only 34 percent approving.

Though Kast is significantly to the right of Boric, that doesn’t necessarily mean Chileans writ large have followed him there. “You have a lot of social and political mobilization on the left, but it is not well organized and articulated politically,” Roberts, the Cornell professor, explained. And, “in the mind of the average voter, Jara represents continuity with the Boric administration.”

There are also structural factors at play. “Over the last 10 years, what you see in Latin America is systematic anti-incumbent voting,” Shifter noted. “I think we shouldn’t necessarily see this as a durable shift.”

Ultimately, though, voters’ priorities had changed from four years earlier. When Chileans chose Boric in 2021, affordability and quality of life were top of mind. Those issues haven’t gone away—Roberts noted that “there’s been very little economic growth” across Latin American nations in recent years—but as Loreto Cox, an assistant professor in politics at Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, told TMD, “Today, by far, the first priority for voters is crime.”

Roberts agreed. “The political ground has shifted to compete over issues of crime and security and immigration,” he said. “And those are the issues where Kast and the right wing is better positioned to compete than the left.”

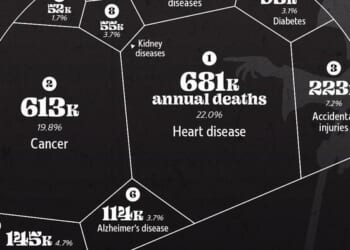

According to data from the World Bank, Chile’s intentional homicide rate has more than doubled from 2015 to 2023, up to 6.3 murders per 100,000 people. Data from Chile’s National Indicators of Organized Crime showed that there were 868 reported kidnappings in the country in 2024, the highest number in a decade, with 40 percent of cases linked to organized crime rings. This crime wave can be largely attributed to foreign—specifically Venezuelan—gangs, including Tren de Aragua, and Chile, a country once broadly considered safe, now has local news stories about dismemberments, trafficking rings, and gang executions.

Ahead of the 2024 Venezuelan presidential elections, for example, members of Tren de Aragua broke into an apartment in Santiago and kidnapped Ronald Ojeda, a notable opponent of Venezuelan dictator Nicolás Maduro, who had fled to Chile for his safety. His body was later found in a suitcase, buried under concrete in a nearby shantytown.

“This change has produced a lot of fear in the population,” Cox said, adding that the crime spike has fueled anti-immigrant sentiment in the country. Beyond the human cost, a June study from Chile’s Universidad Católica estimated that crime costs the country $8.2 billion, or about 2.6 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP), annually.

Chile remains one of Latin America’s safest countries, but fear of gang violence is a new and unwelcome addition. Chilean police have conducted raids on Tren de Aragua spots throughout Santiago this year, but voters clearly want more.

In his security agenda, for example, Kast wrote, “Today, while criminals and drug traffickers walk freely through the streets, committing crimes and intimidating people, honest Chileans are locked in their homes, paralyzed by fear.” He promised to change that, introducing tougher mandatory minimum sentences, creating a new police force modeled on the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, and constructing new, maximum-security prisons, which would completely isolate gang leaders from any outside contact. Kast even toured the infamous CECOT prisons in El Salvador, which were developed by the country’s right-wing President Nayib Bukele after he took power in 2019.

That much of this gang activity can be traced to foreign groups has buoyed Kast’s immigration crackdown agenda. He’s called for installing a de facto “border shield” to counter illegal immigration, which includes digging ditches, propping up walls, and setting up surveillance cameras on Chile’s northern border. Moreover, he’s pledged to round up “all” illegal immigrants and place them in detention centers before ultimately deporting them. “No one who enters Chile through backchannels will ever be able to legalize their situation,” Kast said in September.

Following President Donald Trump’s inauguration in January, Kast was on the radio. “Our ideas already won—they won in the United States, they won in Italy, and they won in Argentina,” he said. “We are going to win, too.”

On Sunday evening, during his victory speech, Kast told his supporters that “Chile cannot get used to fear, and Chile cannot get used to fire. Chile will be free from crime again.”