At the time of his death in the summer of 1987, James Burnham was falling into obscurity. Today, though, his work has surged rapidly in prominence on the right, especially among some of Donald Trump’s most ardent supporters. The reasons for this merit close attention.

At one time, Burnham was widely known as one of America’s sharpest Marxist intellectuals. His most recent biographer, intellectual historian David T. Byrne, ably captures the young Burnham’s contradictions in James Burnham: An Intellectual Biography: a professor of philosophy at New York University, unapologetically bourgeois and completely in his element at black-tie dinner parties, he could respectfully engage Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas. Yet he was also a militant Marxist and a trusted protégé of Leon Trotsky, whom he met and befriended in the 1930s. Distraught over the mass unemployment that was then sweeping across the United States, he admired the ferocious determination of the Marxist revolutionaries who promised an overthrow of America’s supposedly irredeemable capitalist system. Byrne writes that he “loved the idea of violent revolution.”

Yet Burnham was too intelligent and humane to remain impressed with the Soviets for very long. In 1940, his life took a decisive turn when he broke with Marxist-Leninism. Trotsky and his acolytes denounced him as a nefarious traitor. But Burnham would go on to compose what Byrne correctly identifies as “two of the most successful political works of the 1940s”: The Managerial Revolution (1941) and The Machiavellians (1943). He became a public intellectual, appearing regularly in journals of the Left-liberal New York intelligentsia such as the Partisan Review. He was even recommended by George Kennan to help with anti-Communist efforts at the Office of Strategic Services, the forerunner of the CIA.

That was a harbinger of more changes to come. Having once defected from the Marxist vanguard, he eventually became persona non grata among New York’s liberals, too. They could not abide his adamant opposition to Communism or his refusal to see McCarthyism as an unequivocal evil. So he found himself politically homeless yet again, until he helped William F. Buckley, Jr. found National Review in the fall of 1955. He would write hundreds of columns and articles for the magazine and its offshoot, the National Review Bulletin, until his short-term memory was impaired by a stroke in 1978.

Though he was forced to wander from tribe to tribe, his own point of view remained fairly consistent. He thought of himself, not as a partisan of any particular ideology, but as an uncompromising realist committed to hard-nosed assessment of life as it was, not as it should be. His writing was marked by what longtime National Review senior editor Jeffrey Hart described as “stoic detachment.” His constant concern while at the magazine was to avoid undue polemics and make an even-keeled argument that conservatives could be capable of governing in a responsible manner.

His conservatism was layered, and it came on him gradually. But it was indisputably principled and sincere. Byrne writes that “the young Burnham was a Marxist who believed revolution could regenerate the world. The middle-age Burnham was a Machiavellian who believed that the ruling classes must be resisted for tyranny to be thwarted. The most mature Burnham embraced Burke.” His most satisfying and compelling book, 1964’s Suicide of the West, is also his most conservative. Hart once speculated that if it had been published in 1987, when the full ravages of untrammeled liberalism had become more apparent, it might have been a bestseller along the lines of Allan Bloom’s The Closing of the American Mind.

Suicide of the West was republished in 2014 in a handsome edition by Encounter Books, with thoughtful introductory reflections by John O’Sullivan and an overview by Roger Kimball. The Managerial Revolution and The Machiavellians are also freshly available in inexpensive paperback editions. And Byrne’s biography was preceded in 2002 by Daniel Kelly’s lengthier and even more sympathetic James Burnham and the Struggle for the World. Today, conservatives of diverse varieties invoke Burnham to critique the “soft managerialism” that has grown ever more heavy-handed and unaccountable in its domination of public and private life.

Of Managers and Machiavels

The Managerial Revolution, Burnham’s first book after his break with revolutionary socialism, is destined to remain a significant if imperfect piece of work. Its provocative thesis stirred controversy immediately upon publication. The socialists were right that capitalism would soon be obsolete, Burnham argued, but wrong that socialism would take its place. Instead, “managerialism,” the rule of managers and experts who did not need to own property, would define the regimes of the future.

In a 1943 essay “On Historical Pessimism,” the French political thinker Raymond Aron criticized The Managerial Revolution for its dark fatalism and its spurious prediction that Nazi imperium, however modified, would survive the war. Aron, who later became close to Burnham, believed he had been far too quick to proclaim that the bourgeois liberal order was doomed. As Byrne points out, writers such as Friedrich Hayek in The Road to Serfdom (1944), Peter Drucker in The Future of Industrial Man (1942), and Ludwig von Mises in Bureaucracy (1944) were able to accept much of Burnham’s empirical analysis while still mounting powerful defenses of liberal values and the market economy.

Others noted that Burnham was still too indebted to the Marxism he was leaving behind: in characterizing Soviet rule as a particularly despotic form of managerialism (rather than full-blown ideological totalitarianism), Burnham was ultimately echoing Leon Trotsky. Still, George Orwell praised Burnham for his “intellectual courage” and for writing “about real issues.” The “forbidden book” in Orwell’s 1984, Emmanuel Goldstein’s The Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism, is self-consciously modeled on The Managerial Revolution. The staying power of the work shows itself in its continued presence as a point of reference in the literature on bureaucracy and the administrative state.

Burnham’s next book continued his progress away from Marxism. The Machiavellians was the centerpiece of what Burnham, in a 1963 preface, called “the long re-education I had to undertake after seven Trotskyist years.” He remarked that he could not be satisfied with the “pigmy ideologies of Liberalism, social democracy, refurbished laissez-faire or the inverted, cut-rate Bolshevism called ‘fascism’” after having been enthralled by the “gigantic ideology” that was Bolshevism. In his judgment, “only by renouncing all ideology” could one “begin to see the world and man” for what they are. At this point, he found that radically anti-ideological approach modeled in what he called the Machiavellian tradition.

Burnham’s starting point in The Machiavellians is a somewhat vulgarized interpretation of a famous passage from The Prince, in which Machiavelli dismisses “imagined republics and principalities that have never been seen or known to exist in truth.” The conclusion Burnham draws from this passage, that “moral imperatives” invariably create “utopias beckoning from the marshes of…never-never-land,” makes for a poorly argued beginning to an otherwise well-reasoned book. Burnham suggests that Machiavelli locates both politics and ethics “firmly in the real world of space and time and history, which is the only world about which we can know anything.” But by radically “terrestrializing” politics and ethics, Burnham abandoned Marxist atheism in favor of the equally dubious atheism he attributed to the great Florentine. It is worth recalling that this, too, was a stage and not a destination on the journey: shortly before his death, Burnham returned to the Catholic faith in which he was raised.

The rest of the book is more sophisticated. Burnham persuasively argues that Machiavelli was more suspicious of the few, who are endlessly compelled to dominate others, than of the masses, who want to be left alone. This is the same cast of mind that he finds in the 20th-century Machiavellians whose work he goes on to examine. The sociologist Robert Michels, for instance, discerned in Machiavelli’s writing a permanent distinction between “the ruler type and the ruled type,” which made true popular government impossible. Michels called this dynamic “the iron law of oligarchy.” Awareness of this law, Burnham argues, makes the Machiavellians ever-suspicious of the unscrupulous and naturally tyrannical few.

Burnham was most sympathetic to the most liberal-minded of the Italian neo-Machiavellians, Gaetano Mosca. Mosca’s 1896 book, The Ruling Class, conceded the “existence of a minority ruling class” as a “universal feature of all organized societies of which we have any record.” Despite this, Mosca felt it was possible to cultivate and encourage “liberal” as opposed to narrowly “autocratic” elites. In his view, the natural and inevitable “struggle for pre-eminence” must be guided and informed by “laws, habits, [and] norms” that allow for decent and moderate political life. Like Mosca, Burnham came to believe that refusing to “expect utopia or absolute justice” did not have to mean careening into relativism or abandoning civilized moral norms.

Real Realism

As Burnham emphasizes, the 20th-century Machiavellians never endorsed totalitarian politics or moral nihilism per se. But neither did they ask where their own residually humane and liberal sympathies came from, and how they could be adequately articulated or reinforced against those determined to bury them. The modern Machiavellians’ “science of power” tended to treat moral precepts as mythical “residues” or “values” that were useful for sustaining social order but not ultimately based in any absolute reality. This fatally weakened their defense of human liberty against the rise of totalitarianism. Their much vaunted “realism” left out crucial dimensions of reality.

Raymond Aron understood this. Like Burnham, he had turned to the neo-Machiavellians to counterbalance the excesses of doctrinaire egalitarianism. He would publish five of Burnham’s books in his distinguished book series, “Liberté de l’esprit” at Éditions Calmann-Lévy in Paris. He admired The Machiavellians for its distrust of unscrupulous elites in an age enamored with expertise. But Aron also appreciated the moral and philosophical limits of Machiavellianism tout court. He was more intuitively sensitive than Burnham to the dangers and limits of what he called “false realism.” In his 1965 book, Democracy and Totalitarianism, Aron argued that “the great illusion of cynical thought” was its obsession with “the struggle for power.” There was “another aspect of reality; the search for legitimate power, for recognized authority, for the best regime.” In sum, “anyone who does not see that there is a ‘struggle for power’ element is naïve; anyone who sees nothing but this aspect is a false realist.”

Burnham himself was fast growing out of this false realism. Between 1943 and 1955, he worked for the Office of Strategic Services and then the CIA itself. That was how he met the young William F. Buckley, Jr. Burnham was in the process of his ouster from the Partisan Review, the catalyst of which was his refusal to condemn wholesale Senator Joseph McCarthy’s campaign against domestic Communism. Though he was ambivalent about McCarthy’s methods, Burnham defined himself as “anti-anti-McCarthyite.” He lamented that liberal intellectuals, no less than Communists, counted McCarthy more dangerous than the high-level Soviet espionage he sought to expose. Byrne describes the self-assurance with which Philip Rahv, editor of the Partisan Review, proclaimed that “Burnham had committed professional ‘suicide’” by refusing to condemn McCarthyism outright. Rahv simply couldn’t imagine an intellectual world outside of the Left-liberal establishment. But Burnham had already begun to write for conservative intellectual journals such as the Freeman. Then he found a home in Buckley’s lively new movement as co-founder of National Review.

He was now unquestionably a man of the Right, though not a particularly doctrinaire one. He thought the New Deal could be modified but not undone. He supported Nelson Rockefeller in the 1964 Republican primaries (and Barry Goldwater in the general election). In 1983, still alert despite his declining health, he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by Ronald Reagan at the White House. Shortly after his death, his old NYU colleague Sidney Hook wrote that “regardless of the validity of his specific theories, [Burnham] was among the most notable figures in the West who recognized the formidable nature of the threat of Communism to the open society.” He described that threat in his anti-Communist trilogy: The Struggle for the World (1947), The Coming Defeat of Communism (1950), and Containment or Liberation? (1953). These works display all Burnham’s celebrated realism about geopolitics in Eurasia, but none of the fatalism, defeatism, or moral relativism that dogged his early career.

He produced two other great books in his late conservative period. The first was Congress and the American Tradition (1959), which began as a series of lectures at Princeton University. It opens with an expression of admiration for the American Founders, who took their bearings from “experience” and realism about human nature rather than succumbing to the allure of utopian speculation. Today, Burnham argues, conservatives “have more realistic attitudes toward human nature” than Left-liberals, “because they recognize that people are not always governed by reason.” They traditionally have favored balance in government and society—between the few and the many, between aristocracy and democracy. Because they support “the diffusion of power,” they “usually favor Congress over the president.”

By contrast, Left-liberals were coming to favor managerial government by expert-led independent agencies—in other words, an administrative state. Burnham was among the first and most potent critics of this tendency in progressive thought. “Like the Carolingian Mayors of the palace in eighth century France,” he told his Princeton audience, the bureaucracy “not merely wields its own share of the sovereign power but begins to challenge the older branches for supremacy.” Ambition was no longer sufficiently checking ambition.

In a 1959 piece for Human Events titled “The Bureaucracy: The Fourth Branch of Government,” Burnham condemned the tendency of bureaucracies to usurp the roles assigned in the constitution to America’s three federal branches. “In a process well known to modern Washington, the official, who may be the Secretary or Assistant Secretary of one of the major departments becomes the dupe or tool or front of the permanent civil servants whom he is assigned to direct.” At this mature stage of his intellectual development, Burnham’s “science of power” had become constitutionalized. It led him to favor the preservation of liberty in the American political context as the founders had prescribed. That was why, as early as 1959, Burnham was able to diagnose the problem of what is now called “the deep state.”

Suicidal Ideation

Burnham’s last major book, published in 1964, was Suicide of the West: An Essay on the Meaning and Destiny of Liberalism. Roger Kimball has aptly described it as being at once a period piece and a work of enduring political reflection. Its setting and examples date from the long Cold War. But, for the most part, the book remains as relevant as ever. Burnham’s perspective can still be characterized as hard-boiled and realist, even if the tone is decidedly less detached than in his previous writings. In his overview, John O’Sullivan describes Burnham’s attitude as that of “an engaged and passionate writer responding fiercely to events in the world that strike him as something between a tragedy and an outrage.”

In Suicide of the West, Byrne finds “the final thinker that nourished Burnham: Edmund Burke.” It’s a defensible claim, even if Burnham only mentions Burke once in a 364-page book. Burnham devotes favorable attention to the great conservative political philosopher Michael Oakeshott’s Rationalism in Politics (1962), whose elegant critique of abstract rationalism applied to politics has some affinities with Burke’s thought. Moreover, Burkean themes are richly present throughout Suicide of the West. The book is shot through with a deep-seated suspicion of revolutionary innovation. It contains a rousing defense of conservation and reformation as inseparable goods. And it scathingly indicts the inebriated faith in historical “Progress” that besotted so many of Burnham’s former allies on the Left.

Most liberals in Burnham’s time would not have expressed their faith in progress and “human perfectibility” in the exuberant terms of a French philosophe such as the Marquis de Condorcet. But, Burnham insists, few if any intellectuals of a liberal bent would dare admit that any “pending political, economic or social problem” is “just plain insoluble.” For rationalists and so-called “progressives,” there are no political problems “of which there is no ‘rational’ solution at all.” They have succumbed to what the French political philosopher Bertrand de Jouvenel called “the myth of the solution” and look with contempt on provisional “settlements” rooted in compromise, good sense, and thoughtful adjustment to changing circumstances.

Nonetheless, Burnham dedicates his book to “all liberals of good will.” He is not contemptuous of liberals per se and clearly wishes to free them from their self-destructive progressivist complacency. But after describing the “contraction” of the Western world—its decline in power, territory, prestige, and above all, self-confidence—he speaks bluntly, even brutally, about the “suicide” of the West. He initially professes to use the term not as a value judgment but merely as “an appropriate and convenient shorthand symbol for dealing with the set of facts” he has previously outlined. But any careful reader soon recognizes that the West’s suicide appalls Burnham. This is not a “value-free” exercise in political analysis.

What is a liberal, and who is the quin-tessential liberal, according to Burnham? Rather than providing an abstract or theoretical definition, he appeals to “the plain common-sense fact…that everybody knows Eleanor Roosevelt was a liberal, just as everybody knows that Fido, who runs around the yard next door, is a dog…. Whatever liberalism is, she was it. That’s something we can start with.” This is more effective as a definition of the Left-liberalism Burnham wants to rein in than of liberalism full stop. Mrs. Roosevelt may have had laudatory sympathy for the underdog and a keen distaste for racial injustice. But she mistook Communism for “the New Deal in a hurry,” to use the revealing words of Harry Hopkins, one of the New Deal’s chief managers and top FDR advisor. Mrs. Roosevelt placed undue faith in the United Nations and international law, and she was excessively fond of meddlesome government “do-goodery.” Her “liberalism” was more progressive, more statist, and more rationalist than the older and more sober classical liberalism that sometimes overlaps with common-sense conservatism.

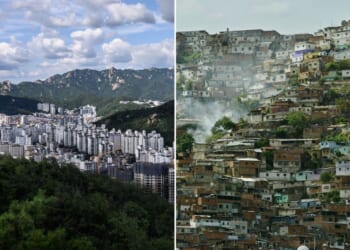

Left-liberalism of the sort embodied by Eleanor Roosevelt was a global phenomenon. One could see it on display in France’s paper of record, Le Monde, no less than in The New York Times and The London Sunday Observer (now folded into The Guardian). Left-liberals blamed segregation solely on white racism and had confidence that racial segregation could be effortlessly abolished in one fell swoop. They had naïve confidence in the virtue of tolerance (except for conservatives), the efficacy of minimum wage laws, and the necessity of negotiations with the Kremlin. They directed selective indignation at the authoritarian regimes of the Right, while indulging the revolutionary dictatorships of the Left such as the “exotic” Chinese Communism of the mass murderer Mao Zedong.

Burnham, on the other hand, counseled Burkean moderation. He believed the tendency to “segregate” in one way or another was inherent in human nature, which made him a gradualist when it came to addressing racial discrimination. He saw that coercive efforts to “integrate” every school, institution, and neighborhood would do more damage than good. But he loathed crude discrimination and mercilessly scorned the conceits of radical segregationists who disparaged the innate capacities of all black people. Today, some populist paleoconservatives, following Samuel T. Francis, have taken advantage of Burnham’s nuanced views on segregation to press him into support for a “genteel” form of white nationalism. But in Suicide of the West, Burnham could not be more clear in his disdain for those who assert “the innate inferiority of the Negro race.”

In essence, he was defending a “tragic” view of life, especially as embodied in “pre-Renaissance thought and literature, Christian and non-Christian alike.” Near the end of Suicide of the West, Burnham praises Christianity for its ability to assuage human guilt through repentance and the sacrifice of the Incarnate God on the cross. In contrast, Left-liberalism, by holding out the fanciful hope that the ills of humanity and the world can all be solved, gives rise to all-consuming guilt. Left-liberal pieties cause their adherents “to feel obligated to try to do something about any and every social problem, to cure every social evil.” This leads directly to a foreign policy guided less by prudence and strategy than by abjection and sentimentality.

Modern Enthusiasts

Since Burnham wrote Suicide of the West, Left-liberal guilt has morphed into open and implacable self-loathing. What the philosopher Roger Scruton called the “culture of repudiation” has filled many young people with hatred toward the sovereign nation-state, the bourgeois family, the Christian religion, and the very idea of the West as a cherished inheritance. The suicidal tendencies Burnham identified have only grown more aggressive as millions of Americans have been deformed by the profusion of anti-American propaganda and gender ideology in elementary, secondary, and undergraduate education.

Still, Burnham thought it just possible that ordinary Americans would continue to resist decayed liberalism and its ideological modes of thinking. If Orwell could maintain his faith in the “proles,” conservatives should be allowed to place some non-utopian hopes in the residual good sense of “the people.” In the quarter-century between The Managerial Revolution and The Suicide of the West, Burnham had left his fatalism behind. He no longer believed the future was set in stone.

Much of the renewed contemporary interest in Burnham’s thought arises from his critique of managerialism, his theory of elites, and his warnings about the threat that the bureaucratic state poses to political freedom. (See, for example, “James Burnham’s Managerial Elite,” by Julius Krein in the Spring 2017 issue of American Affairs, and Samuel T. Francis’s magnum opus Leviathan & Its Enemies, posthumously published in 2016.) There is value in this approach, but it also risks obscuring some of the later developments in Burnham’s thought. Francis, for instance, tends to focus almost exclusively on The Managerial Revolution and The Machiavellians. This produces a preoccupation with, as Byrne puts it, “the struggle for power between two classes: the elites and the nonelite masses, or between the dominant ‘exploiters’ and ‘Middle Americans.’” Like Burnham in his early career, some of his modern enthusiasts tend to make power the alpha and omega, the end and means of the human world, at the expense of the larger principles and purposes that should inform the exercise of freedom. Francis’s keen insights into the divisions that animate American social and political life are marred by a crude “racial realism” (or white identity politics) and by the pseudo-realism that Raymond Aron warned against.

There are also those who have seen inchoate themes of Burnham at work in what Byrne calls Donald Trump’s “domestic worldview,” especially his emphasis on “elites and the ways that they undermine democracy.” There is some truth to this claim, even if it can be safely said that Trump, unlike Reagan, has never read or been inspired by James Burnham. The posthumous revival of this powerful thinker may produce fruit. But it also takes careful scrutiny to sort the wheat from the chaff, in terms both of Burnham’s own thought and of his modern readers’ fidelity to it. James Burnham was a worthy political thinker who liberated himself from revolutionary activism gradually, over the course of decades. If we attend to them carefully, his writings still reward our sustained critical engagement—both for their wisdom, and for the places where they go astray.