Unlike most assets, gold is both relatively rare and doesn’t easily deteriorate. Almost all of the gold ever mined—nearly 7 billion ounces, or enough to fill four-and-a-half Olympic swimming pools—is still around, whether it be in the form of gold bars and coins, fine jewelry, or advanced electronics.

Adrian Ash, director of research at BullionVault, an online precious metal marketplace, says that permanence is part of gold’s appeal. “It’s nobody’s debt. It’s nobody’s to control,” he said. “It’s nobody’s to default on, and it’s no one’s to say, ‘No, you can’t have the value of this,’ particularly if you’re holding it within your own borders.”

That durability has turned gold into a robust strategic asset—both for individuals and institutions, including states.

In 1999, a New York Times op-ed famously asked, “Who Needs Gold When We Have [Alan] Greenspan?” European central banks were selling off their gold reserves, confident that a dominant greenback and victorious Western-led order was making the metal obsolete.

But that confidence appears to be eroding.

“A big surprise for the gold market over the last three years is that central banks have suddenly started buying large amounts of gold again,” O’Connor said. “That really held gold prices up when they probably would have gone down normally.”

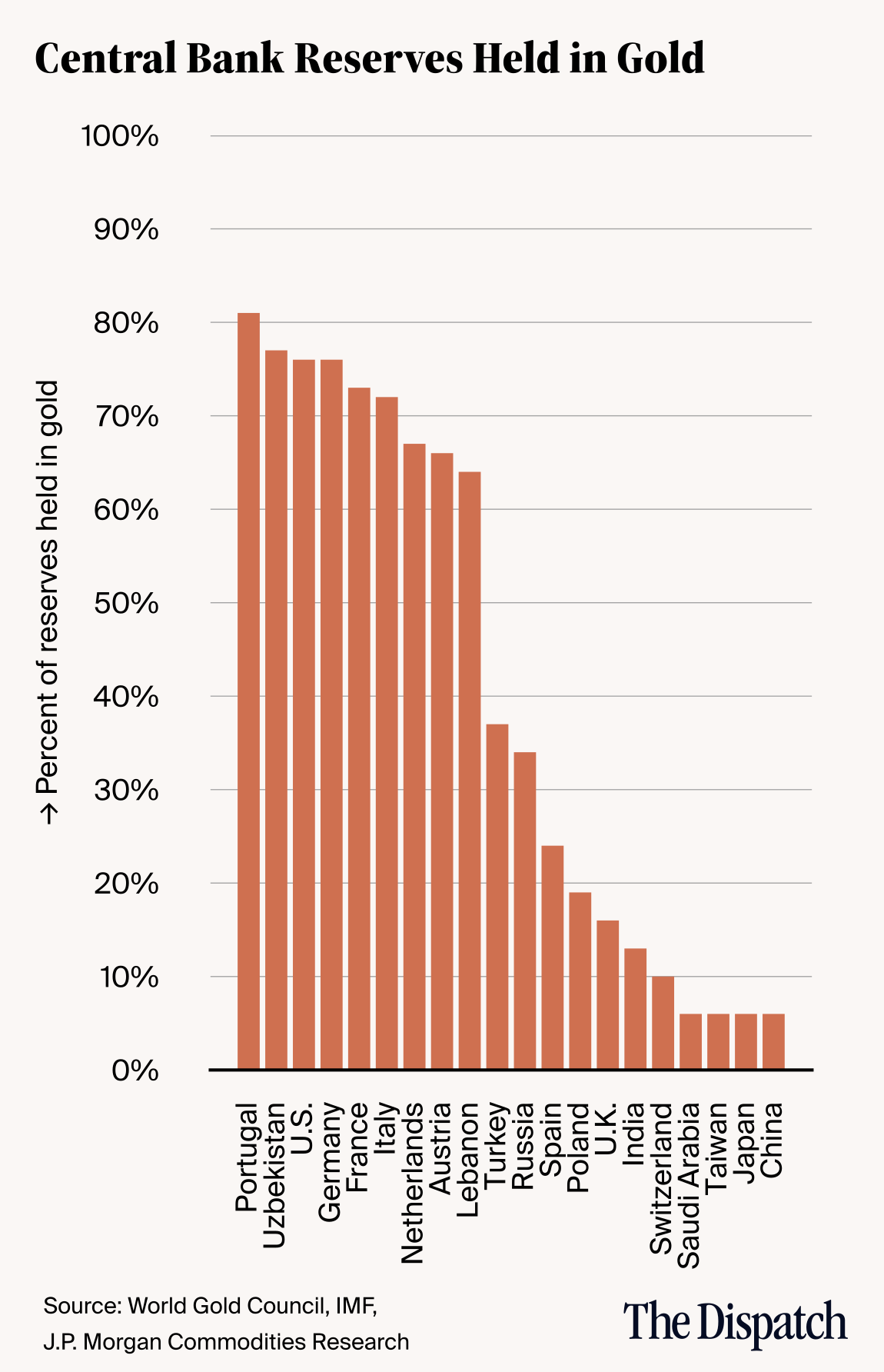

Central banks have long held gold in their reserves—the U.S., Germany, and France currently hold more than 70 percent of their reserves in the metal. But over the past few years, China, India, Poland, Turkey, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Brazil have also started quickly increasing their gold reserves. And between 2022 and 2024, global central banks collectively purchased around 1,000 tons of gold a year. While the U.S. dollar remains the dominant global reserve currency, this year’s purchases have made gold the world’s No. 2 central bank asset, ahead of the euro—reflecting a broader push to hedge against Western currencies and the U.S.-led global order.

Central bank purchases have provided a steady floor for the market, but they’re not responsible for the year’s rise. “The reason that prices have gone nuts this year is that, in 2025, you have seen a real return of private gold investment flows,” Ash said.

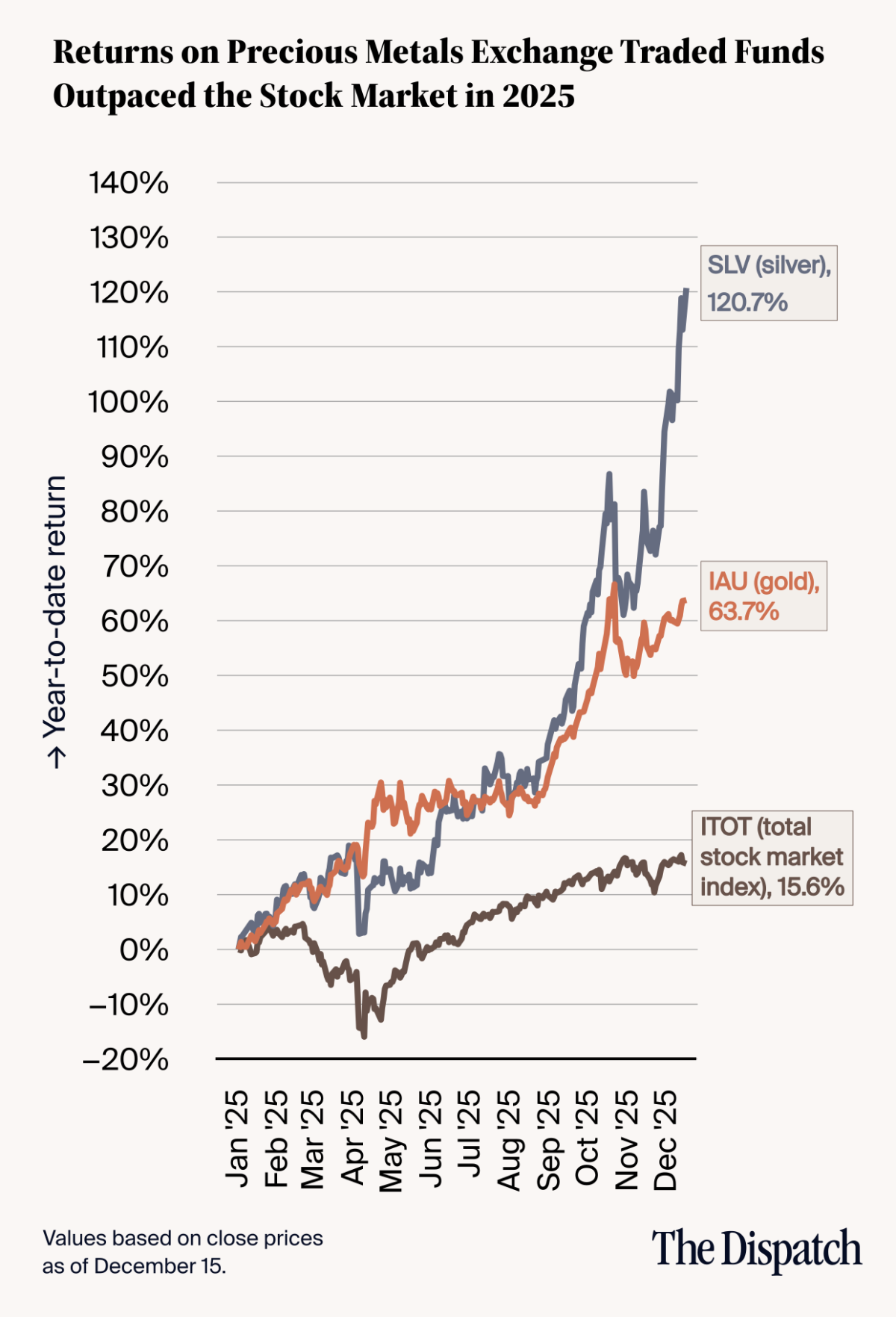

In the U.S., that demand has come overwhelmingly from investments in exchange-traded funds (ETFs) like BlackRock’s iShares Gold Trust and State Street’s SPDR Gold MiniShares Trust. These funds—which trade on public markets and allow retail investors to buy into gold without having to purchase and store physical gold bullion or jewelry—have attracted more than $40 billion in investment this year. Silver ETFs have seen similar inflows, though silver’s more volatile nature makes them higher-risk investments, and it doesn’t have the same cultural appeal as owning gold.

“The reason [gold has] gone up so quickly this year seems to be [ETF] investors,” O’Connor said. “It’s been a big and long run of positive inflows this year.” Retail investors aren’t the only ones purchasing ETFs either—institutional investors like pension funds are also leveraging the low cost of ETFs to expose themselves to precious metals. Countries like China are also seeing quick growth in demand for gold-backed ETFs. Chinese gold ETFs have reportedly pulled in more than $13 billion in 2025, making China the second-largest purchaser of gold ETFs this year and the fifth-largest total market behind the U.S., U.K., Switzerland, and Germany.

China, which has deep cultural ties to gold, is also driving significant demand for tangible metals. “Demand for physical gold, particularly jewelry, bars, and coins, is dominated by demand in India and Asia, and particularly in China,” Tom Brady, a professor of economics at the Colorado School of Mines and former executive in the mining industry, told TMD. As countries with cultural demand for gold have grown richer, their demand for the metal has also grown. Indian households alone hold around 34,600 tons, or more than $4 trillion, of gold, much of it in the form of jewelry—so much that the Indian government is looking for ways to bring that hidden wealth into the economy.

Gold’s rapid rise, however, is being overshadowed by its volatile little sister, silver. While the two often move in parallel, silver is more speculative and tends to rise and fall much faster. “When gold goes up, silver tends to go up 80 percent faster. When gold goes down, silver goes down faster as well,” Ash said. “I’ve likened it in the past to gold on crack. Whatever gold is doing, silver will do with bells on.”

For many investors, silver’s much larger supply and cheaper price-to-weight ratio make it an attractive alternative to gold. “It’s a way of buying gold that feels cheaper, because the individual units are smaller,” O’Connor said. It also makes silver attractive when investors want to bet big that gold prices will increase. “You can also think of it as being like a leveraged play, where if you think gold is going to go up, that usually means silver is going to go up even more.”

Gold has few industrial uses, but silver is an essential component in many modern technologies, such as solar panels, electric vehicles, and medical devices. Industrial uses account for around half of all silver demand, making the metal prone to shortages and volatile price movements. The lease rate for silver—the price at which the metal is borrowed in the wholesale market, often for industrial use—has spiked several times this year, suggesting that demand is outpacing supply.

“Those lease rates went ridiculously high over this year because there just isn’t enough silver,” O’Connor said. “It’s very easy to get a squeeze on the silver price.”

Gold and silver’s rally reflects an investor base—of states, companies, and individuals—trying to hedge against declining Western paper dominance, and a bubbly stock market, held up by less than a dozen companies, all heavily involved with AI. Those gains could fade out—as they did in the 1980s—but banks aren’t predicting a change any time soon. In its most recent 2026 outlook, J.P. Morgan set a fourth-quarter price target of $5,000 per ounce for gold, up around 15 percent from its current price, and Goldman Sachs estimates gold will hit $4,900 by the end of 2026.

And if markets stabilize and faith in fiat returns, there are always White House decorators to sell to.