Americans of all stripes are growing more radical. A universal cynicism about the status quo has led those on the right to flirt with nativist nationalism; on the left there is a growing attraction to more radical forms of socialism. In America, political violence is on the rise, and the right and left increasingly see themselves as bitter enemies in an existential conflict. Internationally, the liberal world order seems to be cracking. Everything feels anxious and uncertain. I am, of course, talking about the 1930s.

The 1930s (indeed, up until our entry into the Second World War) were an era in which Americans on all sides were questioning long-held assumptions about our system of government. The original America Firsters thought we had been far too open with immigration and that our military involvement in World War II was a waste of resources that should be used to serve Americans. They sympathized with European fascist critiques of the liberal west. On the left, there was a growing attraction to communism. William Z. Foster published Toward Soviet America, making the case for a communist revolution here. The free market, the new socialists thought, was a failed experiment. It was also an era in which all sides, increasingly, seemed to blame the Jews for whatever was going wrong.

In many ways, this period was more intense than our current one. The Great Depression makes any economic complaints we have look paltry. The rising fascists and communists in Europe in the ’30s make our radicals look relatively tame. But the widespread sense of anxiety might be familiar to us. So too might be the sense that an old consensus is falling apart.

But America remained a free republic. How? To fully answer that question would probably require volumes of writing. But one interesting experiment in the 1930s may have helped.

John Studebaker, the superintendent of public schools in Des Moines, Iowa, who in 1934 became Franklin D. Roosevelt’s commissioner of education, was worried about the rise of radicalism and what he saw as a decline of civility, and he wondered what he could do to get Americans to talk and reason with one another. What would it take to cultivate a public capable of maintaining our republican form of government?

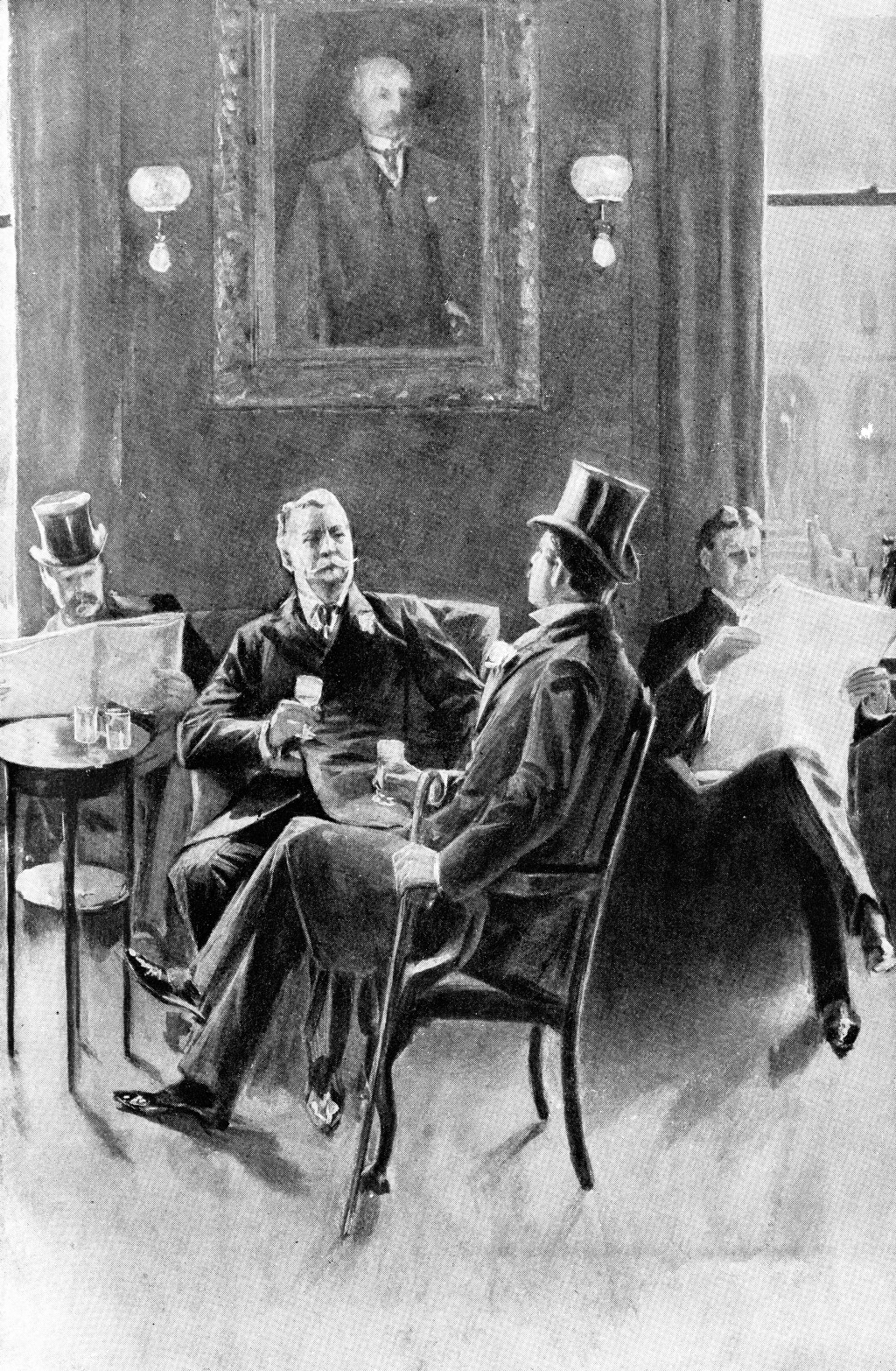

His answer was what became known as the Public Forum Movement. Democracy, he thought, depended on free and open discussion. Beginning in Des Moines in 1932, Studebaker would organize public conversations between scholars and local leaders. Topics included fascism and liberalism, the impact of the New Deal on black Americans, and whether the tariff power should belong more to Congress or to the president. Studebaker thought that, by cultivating a nonpartisan space for open disagreement, people would come to respect one another better, and would be less likely to express themselves via violence and disorder.

And it seems that Studebaker’s vision actually worked. Within the first few years, Studebaker reported 60,000 participants, and forums began to spread from Seattle to Minneapolis to New York City. Millions of Americans attended public forums with their neighbors and had reasoned discussion about the big questions of the day. Here was the take of the editor of the Des Moines Register, observing the effect of the forums on the local community:

Free speech, thanks to the forums, is taken a little more for granted; is made a little less terrifying; our conservative shiverers shiver less, and our half baked agitators have been a little deflated. There appears to have been a slight degree of immunizing against quack social programs. … The plain implication, to us, is that free discussion has promoted orderliness here, and that the practice of suppressive tactics by the authorities in some other cities has been provocative of disorder and disturbance.

In our own day of political anxiety and anger, such an approach ought to appeal to many Americans, 80 percent of whom say they are worried about the rise of incivility and the threat of political violence. Attendees of the Public Forum felt that these events really were making their cities healthier and more civil communities. Perhaps events like this could do the same for us today.

How are societies radicalized? How does authoritarianism come to replace freedom? How does truth give way to ideology? One of the thinkers who thought most deeply about these questions was Hannah Arendt, the German-Jewish philosopher, who lived through the radicalization of German society under the National Socialists.

For her, among the key factors that laid the groundwork for the rise of totalitarianism were mass loneliness; a loss of a shared, public world; a universal cynicism; and ideological thinking. In 2023, the scholar Michael Weinman explained these factors well:

The core insight to which commentators on Arendt have returned in recent years is her sense of the loss of the common world. That world could exist, she believed, only if “differences of position and the resulting variety of perspectives notwithstanding, everybody is always concerned with the same object.” As our lives are increasingly shaped by the hyperpolarization of political communication and the online silos in and through which we interact with others, any activities that might otherwise have prompted us to enter and participate fully and freely in a shared civic realm have all but vanished. Integral to Arendt’s picture of a healthy or at least decent polity is her conviction that such a “space of public appearance”—a public forum in which all citizens can exercise their distinctive human qualities—is possible only when there is a common world, shared by everyone on the basis of a common sense and the common object of perception that serves as its ground.

Would-be authoritarians need to work to atomize the public. When we separate from one another, we become weak and helpless before the state. And without a community of people who can help us to make sense of the world, we begin to lose touch with reality and to experience a sense of anxiety, confusion, and vulnerability about a complex and changing world.

The one who will succeed in garnering power is the one who can use mass media to give vulnerable people a sense of community, clarity, and direction. The Nazis were effective in large part because they so skillfully used the radio, the cinema, and printed propaganda. When the isolated citizen listens to a charismatic voice that tells him the answers and solutions to all his worries, he is much more apt to be swayed than when he is connected to his neighbors.

Robert Putnam, the author of the acclaimed 2000 book Bowling Alone, began his scholarly life by studying the health of democracy in Italy. In the 1970s and ’80s, Italy experienced its own period of turmoil, with various socialist fronts and fascist holdovers engaging in street violence and assassinations. Italy had recently moved to a regional governance structure, devolving more power to more local forms of government. What Putnam found, later published in the book Why Democracy Works, was that the common thread between regions where local, democratic governments were effective and responsive to community needs was the existing health of the region’s community life. Indicators of healthy democracy were to be found in the degree to which a region’s citizens went to Church, belonged to clubs, and felt they had strong social bonds.

This comports with Arendt’s idea that a strong community life is a prophylactic against radicalism. It is in the local community, she thought, that we establish together a shared sense of reality. Through the push and pull of different ideas we come to a baseline sense of the world around us. In doing this, we become less susceptible to the one-sided pictures of reality offered to us by media personalities or politicians. If, today, we worry about the radicalization of isolated individuals who sit and consume ideological content online, the response ought to be cultivating healthier local spaces where people can explore ideas. This strong, local conversation can also cultivate a sense of belonging and agency, which can counter the frustration and loneliness which is radicalism’s soil.

Alexis de Tocqueville, the famous French observer of American politics, worried about the life of the American mind way back in the 1830s. Because Americans were so equal and so free, he observed, they tended to be individualistic. The risk for America was that citizens would withdraw from the life of their communities. If Americans atomized like this, they would be helpless before the ever-growing might of the state.

Despite these worries, de Tocqueville thought that our republic also had the resources to remain free. Yes, our equality and liberty tended to make us more individual, but our culture and our religion made us communal. Americans used to love forming and joining clubs. By participating in community life, Americans learned how to participate wisely in a republic, they developed bonds of social solidarity, and they created centers of influence outside the government, which kept the power of the state within proper limits. So long as we held on to our community life, our sense of virtue, and our religious life, we could be safe from tyranny.

Putnam, famously, has tracked the decline of this kind of associational life since the 1960s. Across almost every measure, we are less involved with each other with each passing decade. But Putnam has also demonstrated that we have experienced periods of weak community life before, and we found a way out. During the Gilded Age, community life fractured due to massive urbanization, increased mobility, and poor housing conditions in the newly crowded cities, but the resilience of American community life showed itself through the founding of organizations that remain(albeit in much-diminished form) today: the Rotary Club, the Lions Club, the Knights of Columbus, and more. These clubs and organizations were not just forms of community: They were communities of moral calling, focused on countering individualism for the sake of the public good.

Today, in an era whose technologies threaten to isolate us in ways that Studebaker and Tocqueville could never have imagined, we need to shore up our avenues of public inclusion and discussion. Americans already spend an average of seven hours a day staring at screens outside of work. How will this number increase in the era of AI, when machines present themselves to us as all-knowing, ever-sympathetic friends? How will we remain connected to our real communities when the wealthiest companies in our country thrive on our isolation?

Americans need to make a conscious, intentional decision to buck the forces that are breaking us apart. For the past four years, this is what we have been trying to do at the Lyceum Movement.

We take our name from the original Lyceum Movement, a cultural force in 19th-century America that hosted free and open public dialogue on philosophy, theology, and government. The Lyceum was founded in 1826 in Connecticut by a farmer named Josiah Holbrook. His aim was “the general diffusion of knowledge and the raising of moral and intellectual tastes” of the public. Frederick Douglass, Mark Twain, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and Henry David Thoreau made their names on the Lyceum stages scattered throughout the country. This movement was a sort of precursor to later efforts like the Chautauqua Institute and the Public Forum Movement. An early participant described the Lyceum Movement’s effects this way:

We come from all the divisions and classes of society … to teach and to be taught in our turn. While we mingle together in these pursuits, we shall know each other more intimately; we shall remove many of the prejudices which ignorance or partial acquaintance with each other had fostered … in the parties and sects into which we are divided, we sometimes learn to love our brother at the expense of him whom we do not in so many respects regard as a brother … we return to our homes and firesides from the Lyceum with kindlier feelings toward one another, because we have learned to know one another better.

In my work with the Lyceum, I have sat with a high-powered attorney and a car mechanic as they considered the true nature of a good human life. I have sat with conservative Christians and progressive liberals as they tried to think through together what AI will do to our society and how we should respond. At the Lyceum, we are not united by ideology, but by the fact that we are neighbors and we share this place together.

We need to talk. When we stop talking, we are tempted to come to blows. When we stop talking, our ability to think critically atrophies, our sense of charity decays, and, in the end, we are left lonely. Now, I don’t suppose that “just talking” will work as a panacea for all of our problems. But the shared search for truth and the shared cultivation of the virtues necessary for shared life are not meaningless, either.