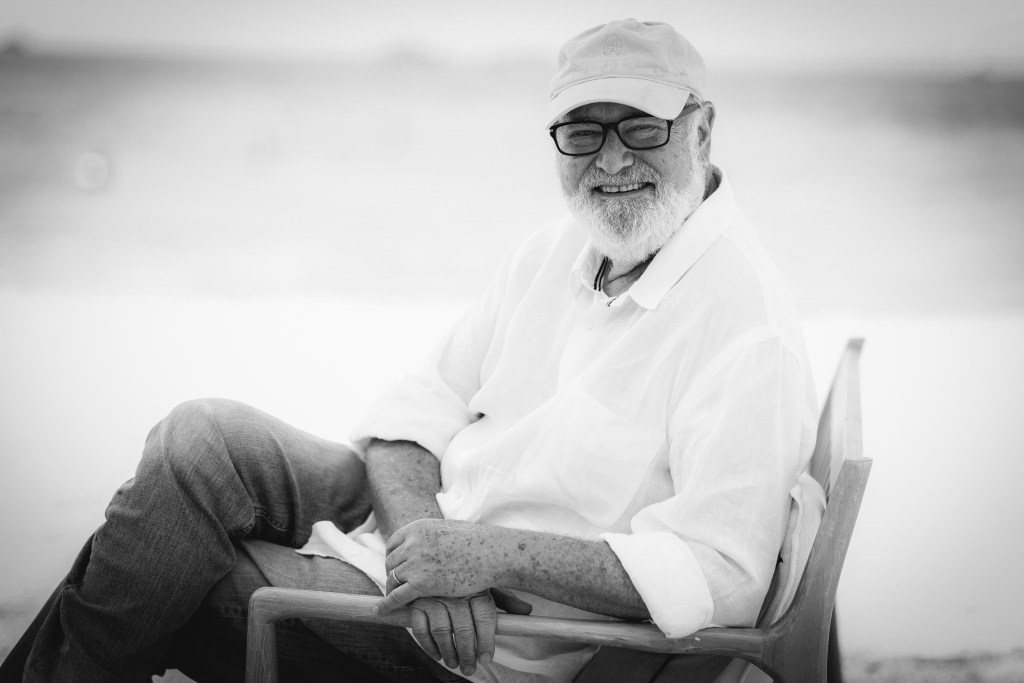

In recent years, there has been much discussion on the topic of nepo babies—the children of famous and powerful people finding their way into important roles in Hollywood or business. Perhaps, had the term been around in 1971, when Rob Reiner was cast as Michael “Meathead” Stivic on All in the Family, that accusation could have been directed at him. His father, Carl Reiner, was the creator of the Dick Van Dyke Show and a member of what has to be one of the greatest writer’s rooms of all time, on Sid Caesar’s Your Show of Shows, which included Mel Brooks, Neil Simon, Joseph Stein (who would go on to write Fiddler on the Roof, among other things), and a half a dozen other comedy, Broadway, and film legends.

But Reiner achieved something that the young and privileged often struggle to achieve: He found his own voice. In 1984, he directed the greatest mockumentary ever made, This Is Spinal Tap, and he followed it up with one of the greatest streaks of successful films in Hollywood history: The Sure Thing, Stand by Me, The Princess Bride, When Harry Met Sally, Misery, and A Few Good Men.

Following his Emmy-winning turn as Archie Bunker’s son-in-law, by the time This is Spinal Tap was released, no one was questioning Reiner’s credentials. When A Few Good Men was released, he became a legend. There was no tone he couldn’t capture—nostalgia, comedy, fairy tale, romance, horror, drama—it was all there in his body of work. He was as deft at making Jack Nicholson erupt in fury as he was in making Meg Ryan and Billy Crystal sparkle with charm or Robin Wright manifest like a beautiful dream.

Reiner and his wife Michele Singer Reiner were murdered last weekend. And from the moment word of their death hit the media, reactions poured in from his collaborators, from actors, film producers, and others who had crossed paths with him.

I met Rob Reiner in January 2024, upon the release of a documentary about Christian nationalism titled God and Country. The film had an obvious political valence—we were coming up on the 2024 election—and Reiner had a long history of political activism on behalf of progressive causes. Reiner produced the film, along with Michele, and I met both of them and interviewed Reiner along with Dan Partland, the film’s director.

It’s rare a person like me (a lowly podcaster and writer from Louisville, Kentucky) finds himself breathing the same air of a Hollywood legend. In a different phase of my life, I played guitar at some events for the Kentucky Derby, and met a string of A-, B-, and C-list notables at those gigs, but they were always brief encounters, and rare was the real, natural, engaged conversation.

My sit-down with Reiner was different. It was immediately apparent that this was a person who just loves the company of other people, who loves to tell stories, who wants to make people feel at home, who wants to get the laugh. Michele was clearly his anchor, a more stoic presence, but clearly and constantly amused by Rob himself.

It is perhaps my favorite interview I’ve ever conducted. Not because I loved Reiner’s film—I had real problems with it, including the ending, which I thought overshot the goal of the storytelling by quite a bit. But Reiner was so present and engaged. He joked and laughed, admitted what he didn’t understand, and showed tremendous generosity of spirit—which I interpreted as a clear revelation of the temperament of a person who could tell the kind of compelling stories he was devoted to for his entire life.

Perhaps the most significant moment of the conversation was when I challenged him over his own political rhetoric, saying that perhaps, now that we have actual Christian nationalists lobbying for roles in the government, and when a person like Donald Trump was (at the time) promising actual “retribution” and militarization, perhaps his own overheated rhetoric about George W. Bush, John McCain, and Mitt Romney (all of whom Reiner criticized mercilessly during their campaigns) was a bit much. And to his credit, Reiner conceded the point.

What no one can deny, regardless of their political beliefs, was that Reiner was a man of enormous heart. His films radiate love, friendship, loyalty, and of course, the heart’s great pain, grief. One also can’t deny he loved his country. While you might have a very different vision of what makes this place special, or what can solve its problems (I certainly did), his investment in American political life came from a place of deep sincerity. A statement of grief published after his death, signed by a number of his colleagues including Martin Short, Billy Crystal, and Larry David, described him as “a passionate, brave citizen, who not only cared for this country he loved, he did everything he could to make it better and with his loving wife Michele, he had the perfect partner.” In our own brief encounter, that kind of patriotic concern was undeniable.

When we finished our interview, he gravitated to his wife Michele, almost instinctively, even as publicists and others chattered about the next interview he needed to get on to. She was clearly his ballast, and it was clear they delighted in one another. As we wrapped, I got teary-eyed and said to Michele, “He reminds me of my dad.” I had lost him just a few years earlier, but there was something to the generosity of spirit, the humor, the hospitality that felt so familiar. Michele hooked an arm around my shoulder and said to her husband, “He gets you, you should do more of these.”

My hunch, and my hope, is that in 50 years, no one remembers the contemptible words that President Trump posted, nearly dancing on his grave. There will be little emphasis on Reiner’s various political donations, or the handful of campaign commercials he produced. Instead, they will remember Billy Crystal’s lovelorn speech at the end of When Harry Met Sally, an ending that Reiner asked Nora Ephron to rewrite mid-shoot because he’d met Michele, and in the new version, he wanted the couple to come together. They will remember Wesley looking into Buttercup’s eyes and saying, “As you wish.” They will remember the bonds of friendship in Stand By Me, and the monster he helped Kathy Bates create in Misery. They will remember Jack Nicholson exploding on the witness stand in A Few Good Men.

They will remember these things because they are images, stories, fairy tales, that remind us what it means to be human, to be afraid, to be courageous, to be brokenhearted. The correct response is not to pontificate on the politics, which are fleeting, but to weep, to laugh, to fall in love, to be terrified, to be brave. And Reiner’s legacy will be the remarkable way he showed us how to embrace it all—the whole of the human experience—in the stories he told.