You’re reading Dispatch Faith, our weekly newsletter exploring the biggest stories in religion and faith. Looking for more ways to support our work? Become a Dispatch member today.

For those of us in the Northern Hemisphere, today is the shortest of the year. For Christians, the fact that the year’s longest night occurs during Advent—as we await the joy of Christmas—is no mere irony. That thought is part of Contributing Writer Hannah Anderson’s meditation on Advent, darkness, and waiting for light in today’s newsletter.

Also on our website today and excerpted below: Thomas D. Howes considers the visible rise of antisemitism among fellow Catholics and explores how the church has met such challenges before. And Baptist missionary and teacher Mark A. Swedberg responds to a recent Dispatch Faith essay on dispensationalism.

I’ll be taking next week off for Christmas, but we’ll be back in your inbox after the New Year. In the meantime, may your holidays be joyous. And thank you so much for reading.

Hannah Anderson: A Dark Season at Advent

The darkness has been gathering for a while now. It wasn’t particularly obvious at first—a lengthening shadow here, a loss of an hour there. But as the weeks progressed and the hands of time were set forward, an undeniable gloom has settled in and with it, a chill. Things that once flourished in light now lie dormant. We go to sleep in darkness and wake in the same.

To be fair, the night has been coming due for a while now. Those high days of summer when we were carefree and daylight seemed to stretch on forever were always going to exact a price. But the loss of light was so gradual that we didn’t really notice it until we were sitting in darkness. And now, those of us in the Northern Hemisphere find ourselves facing the longest night of the year.

Stories We Think You’ll Like

Meteorologically speaking, the winter solstice is easily explained: It is the moment when the Earth’s poles are tilted to their most extreme positions in relationship to the sun, resulting in an exaggerated gap in sunlight between the Northern and Southern Hemispheres. While the global South basks in the light of summer, the tilt of our planet’s axis places the North in darkness. The further north you go, the greater the disparity so that Oslo, Norway, will experience only six hours of daylight while Fairbanks, Alaska, will have less than four. Closer to the Arctic Circle, there will be no discernible sunlight at all—full days of darkness for places like Murmansk, Russia, and Utqiagvik, Alaska.

Those are the facts anyway. But the existential reality of the winter solstice is less reasonable and at least for me, deeply portentous. There’s a heaviness to it, and for some, a visceral despair as the loss of sunlight prompts physiological imbalances in the form of Seasonal Affective Disorder As a child, I remember my father speaking of the encroaching night with a sense of reverence and even humility. My father spent most of his day working outside, so for him the loss of daylight meant the loss of working hours and, to some degree, productivity, which in modern life also implies meaning.“The shortest day of the year is coming,” he’d warn as if he were a prophet and it was his solemn duty to prepare us for what was coming.

So like the Earth preparing for winter, I find myself shutting down as darkness descends. It is harder to wake in the morning, and I’m less eager to venture out in the evenings. My mind tells me that I should be active and engaged, fighting against the chill, pushing back the boundaries of the night. Conditioned for productivity and abundance, I flood the house with lights, crank up the heat, and push through. And yet, I also find my body telling me to wait. To accept that there are dark forces beyond myself and that all my energy and efforts cannot stop them from cycling through.

In such moments, I take comfort in the particularly propitious alignment of the winter solstice with the liturgical season of Advent. At least in the Northern Hemisphere, these weeks gradually bring us to the year’s darkest darkness even as they also deliver us to Christmas. Modern observances often treat Advent as an extension of Christmas, with celebrations and feasting beginning immediately after Thanksgiving, but Christians as far back as the fourth century have prepared for the coming Christ child by sitting in the darkness. Much like the season of Lent, these weeks are for fasting, prayer, and repentance. Strangely enough, we’re supposed to feel unsettled and lost.

In her booklength treatment of Advent, Episcopal priest Fleming Rutledge puts it more directly:

Advent is the season that, when properly understood, does not flinch from the darkness that stalks us all in the world. Advent begins in the dark and moves toward the light—but the season should not move too quickly or glibly, lest we fail to acknowledge the depth of the darkness. As our Lord Jesus tells us, unless we see the light of God clearly, what we call light is actually darkness … Advent bids us take a fearless inventory of the darkness without and the darkness within.”

In this way, the Earth may be better attuned to the purposes of darkness than we are. While we insist on revelry and abundance, nature is content to receive such seasons and sit in night. What for us can be the busiest time of the year becomes for her a time of patience and quiet—a time dedicated to the hidden work of decay, the breaking down and dissolution of the past year’s excesses in preparation for future life.

But as much as Advent is a season of darkness, it is also a season of expectation and it is vital that we remember that the night delivers us to the morning. “Advent” derives from the Latin word, adventus which means “coming” or “arrival.” Something—Someone—is coming and we are waiting for that coming. Christians are waiting for the One whose justice and kindness far outpaces our own. So that even as the shadows lengthen and night descends, even as the things that operate in darkness feel like they grow stronger each moment, hope is not lost. For just as you cannot see the glory of the stars at noonday, it takes the chill of a winter’s night to clarify what is Light and what is Dark. And it is by these same pinpoints of light that we will be guided.

In the final book of the Lord of the Rings trilogy, J.R.R. Tolkien describes such a reality. As the heroes Sam and Frodo are engulfed by the ever-deepening shadows of Mordor,

there, peeping among the cloud-wrack above a dark tor high up in the mountains, Sam saw a white star twinkle for a while. The beauty of it smote his heart, as he looked up out of the forsaken land, and hope returned to him. For like a shaft, clear and cold, the thought pierced him that in the end the Shadow was only a small and passing thing: there was light and high beauty forever beyond its reach.

Today, we may sit in darkness, but we wait in hope. Whether you’re feeling the weight of strained relationships, economic pressures, or civil unrest, the invitation of Advent is to know that you are not alone in the darkness. There is a Light beyond us, and that Light is coming to us. So we entrust ourselves, our neighbors, and our world to the God who is Emmanuel–who has and is and will come. And soon we will celebrate.

For tomorrow, the turn toward Light begins.

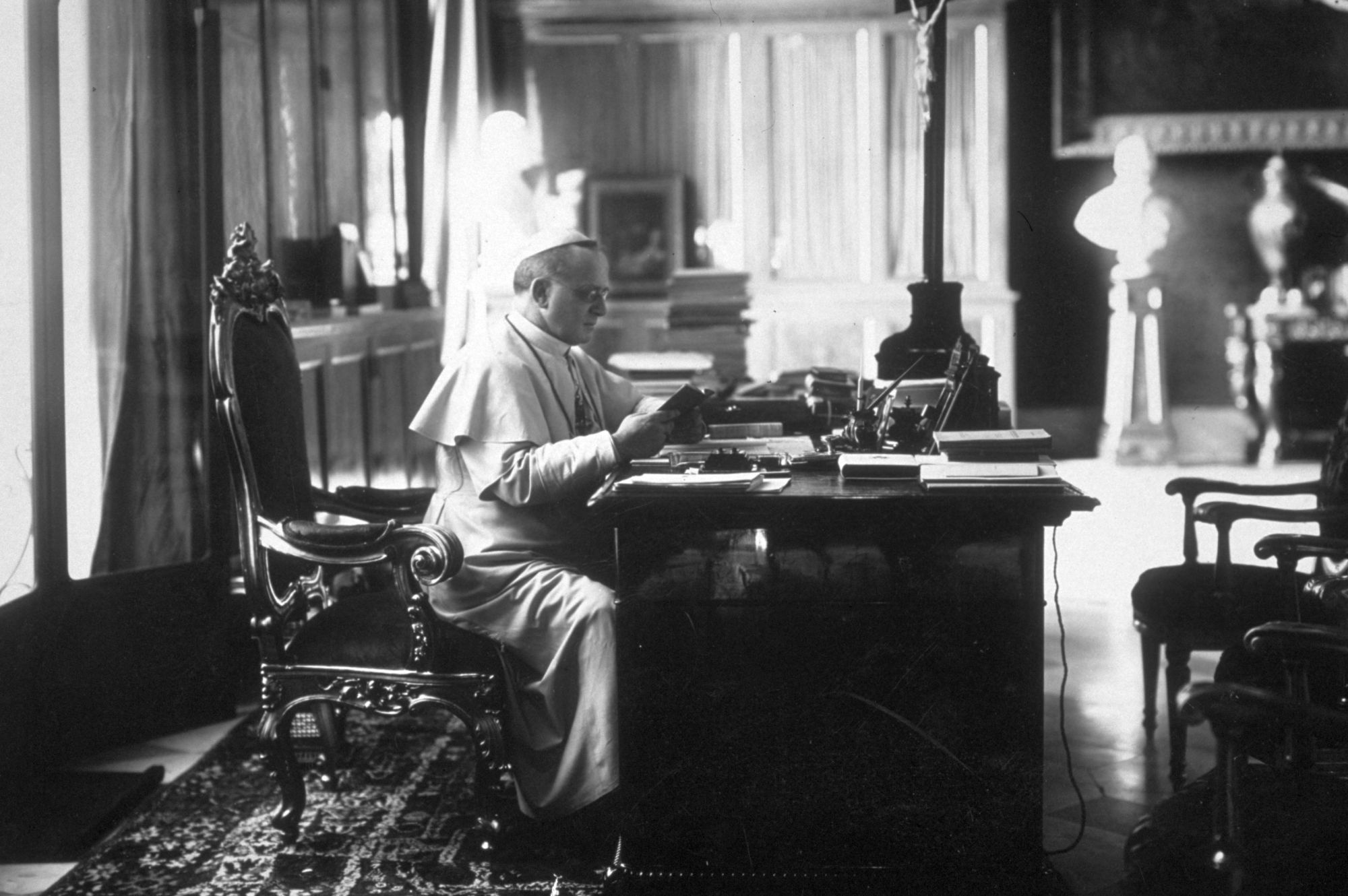

Thomas D. Howes: The Catholic Church Has Faced Antisemitism Before

Both outright violence against Jews and less tangible hatred toward them should be a growing concern. That’s especially true for the Catholic Church, argues Thomas D. Howes in a piece on our website today. In many ways, the moment we’re living in now isn’t new, and Howes explores how fellow Catholics have given in to antisemitism before. But he takes hope for his church in stands taken during the Second Vatican Council, more than six decades ago.

That is why certain moves of the Second Vatican Council in the 1960s were so important. In the Council’s declaration Nostra Aetate, for instance, the world’s bishops united with the pope in changing the conversation about the church’s relationship with Jews, positively affirming the “spiritual patrimony common to Christians and Jews,” and seeking “to foster and recommend … mutual understanding and respect.” It also clarified that Jews hold no collective responsibility for the death of Jesus Christ, countering an old antisemitic accusation that was based on bad theology. The Council also “decries hatred, persecutions, displays of anti-Semitism … directed against Jews at any time and by anyone.” Post-conciliar popes like John Paul II upheld this attitude, referring to the Jews as “elder brothers” in the faith.

The Council likewise addresses the problem of the kinds of political arrangements that foster antisemitism in its Declaration Dignitatis Humanae, which affirms some of the central assumptions of liberal democracy, namely, the civil protection of fundamental rights, particularly religious freedom. This builds on Pope John XXIII’s encyclical Pacem in Terris, which affirms liberal democracy’s emphasis on special civic protection of human rights. What was particularly novel in Dignitatis Humanae was the affirmation of a civil right to religious liberty—a move made possible by the work of people like Jacques Maritain and Charles Journet, two respected Thomists who had also supported the French Resistance against Vichy during World War II.

Mark A. Swedberg: A Defense of Dispensationalism

A few weeks ago, we ran an essay on Christian Zionism that was critical of dispensationalist theology. A few readers took issue with some of the characterizations therein, including missionary and teacher Mark A. Swedberg. Today on our website is his rebuttal and explanation of dispensationalism.

Dispensationalism begins with the idea that God says what He means and means what He says. To put it another way, whatever is written in Scripture should be understood according to the author’s intent and interpreted the way the original readers would have understood it. We are originalists in that way.

My fingers kept wanting to type that dispensationalism begins with the assumption that God says what He means and means what He says. But that isn’t quite right. We believe that God tells us plainly how we are to interpret Scripture—especially in prophetic or predictive Scripture, which is where most of the debate lies. Isaiah writes that the ability to predict the future is what separates the true God from all of the false ones (see Isaiah 41:21-23 and 46:9-11).

Additionally, Moses tells the nation of Israel (Deuteronomy 18:15-22) that what distinguishes a true prophet from a false one is that everything the true prophet predicts has to happen. If he predicts something and it doesn’t happen, he is to be rejected and even stoned. But if it does come to pass, they must listen to him on pain of death. In fact, this was one of Jesus’ arguments to the nation of Israel (John 5:31-37). This presupposes that the prophecy is clear and specific enough to be understood and verified—not the vague words of some Nostradamus-like oracle.

Yes, we do get called “woodenly literalistic.” However, we do understand that Scripture uses figures of speech and different genres of literature, all of which need to be factored in when arriving at the proper interpretation of any text.

More Sunday Reads

- For the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, Jackie Hajdenberg reports on a neighborhood in Harlem adding a menorah to their park’s Christmas display—and what it meant to their Jewish neighbors. “‘We’ve lived in the neighborhood for a long time, and we walk by that park every single day,’ said Erica Frankel, who with her husband Rabbi Dimitry Ekshtut is the co-founder of neighborhood Jewish community group Tzibur Harlem, which co-sponsored the lighting. ‘And we’ve been dreaming that one year there would also be a big public display for Hanukkah in the park alongside the tree.’ The event arose following an inquiry by the couple to the Montefiore Park Civic Association, asking if they could install a large menorah in the park. Instead of a simple ‘yes,’ a broad coalition of civic, Jewish, Black, Dominican and interfaith organizations came together to create the first ‘Harlem Festival of Lights,’ a cross-denominational celebration of both Christmas and Hanukkah. … In a year marked by antisemitism, both close to home and afar — most recently on Bondi Beach in Sydney, where 15 people were killed at a public Hanukkah menorah lighting event — the cross-cultural display of holiday cheer felt especially meaningful to many of the participants. As a sign of the times, however, there was a pronounced police presence in the area. ‘What we are doing tonight, in lighting a menorah publicly in the city of New York, in Harlem, with our friends, with our community members, with our elected politicians, with our police officers here, with all of you here, is nothing short than a reclamation of identity, a reclamation of ancestry and a public announcement that we are here,’ Ekshtut said during his remarks.”

- Earlier this week on his Substack, historian Daniel K. Williams contemplated how the rise of the idea of Santa Claus in the U.S. coincided with the ascendance of a more liberal theological interpretation of Christianity. “By that point, a shift in American religion made it possible for the Santa Claus myth to spread. Most American Protestants were no longer Calvinists, and they now had a much higher view of innate human goodness than an earlier generation of American Protestants had,” Williams writes. “And among some educated Protestants in the North, there was a new belief (influenced by German historical criticism of the Bible) that the essential religious truths of Christianity did not depend on the literal historicity of the biblical gospels. Much of the Bible could be mythical and yet still remain ‘true’ in some metaphysical sense. In the most extreme version of this idea, some liberal Protestants (such as Yale Divinity School professor Douglas Clyde Macintosh) said that Christianity would still be true even if one could prove that Jesus Christ never existed. The idea that myths could be true in a metaphysical or spiritual sense while not being historically true probably would not have made much sense to most Americans in the early nineteenth century. But with the emergence of liberal Protestant theology in the late nineteenth century, this idea did become much more common, even though it remained controversial.”

Religion in an Image