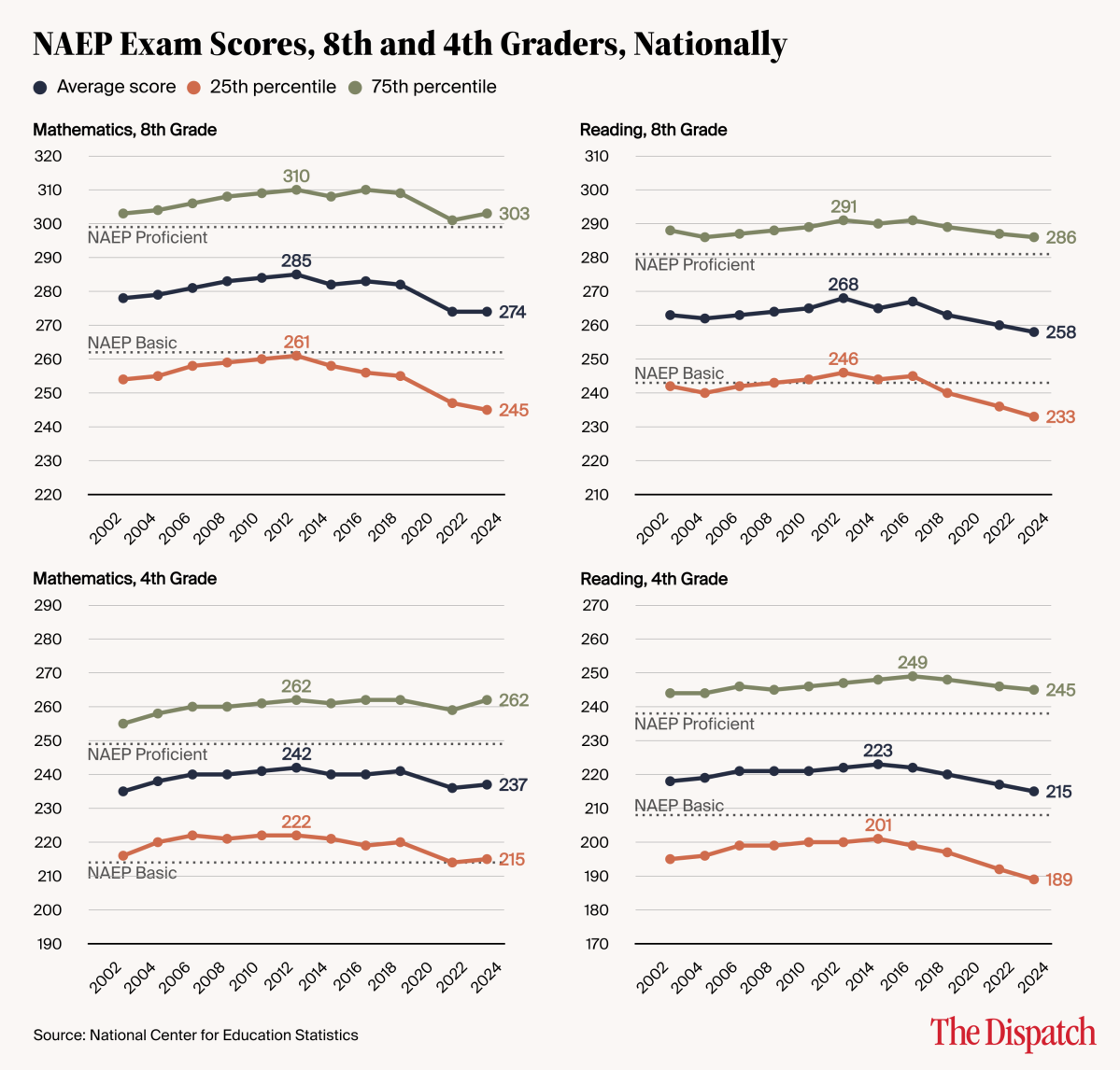

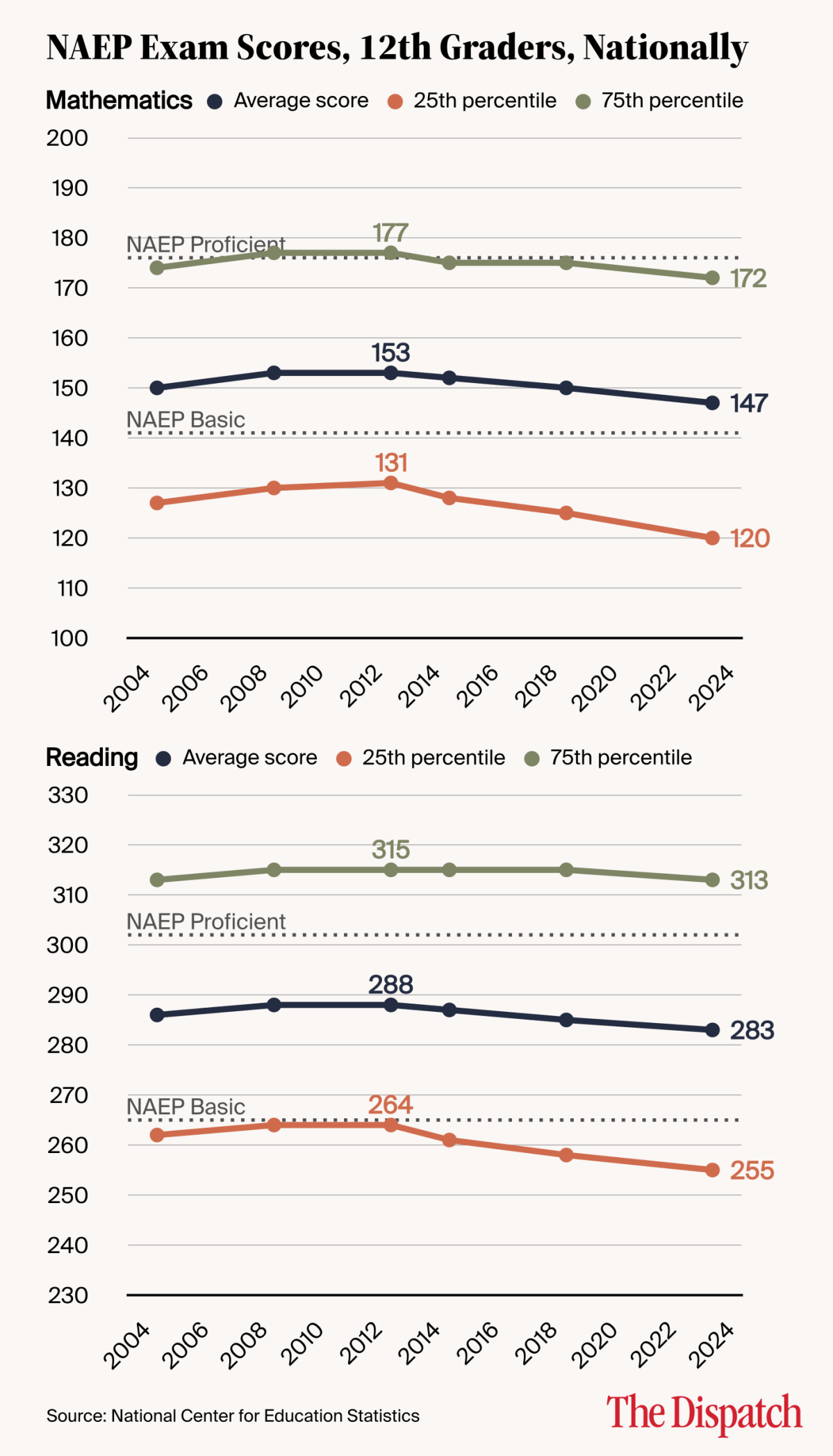

The school closures and other disruptions associated with the COVID pandemic accelerated those declines, of course, but they did not create the slump themselves. “The decline in performance began well before COVID,” Dan Goldhaber, the director of the Center for Education Data & Research at the University of Washington’s School of Social Work, told TMD.

While these declines are occurring nationwide, they are not evenly distributed across the academic spectrum. James Wyckoff, a professor who directs the education policy doctoral program at the University of Virginia, explained that in 2013, eighth-grade students in the 10th percentile of academic achievement were learning about a year more of eighth-grade math than students in the 10th percentile about a decade later. “That’s huge,” he told TMD, adding that the smaller declines of students in the middle distribution still represented several months of learning loss. Students at the top end of the spectrum, however, have mostly managed to tread water, particularly in math.

Why did achievement scores begin to decline in 2013? Rather than point to a single explanation, researchers generally note that a number of different trends coalesced that year to finally reverse factors that had been pushing students’ scores up for decades. And this is no navel-gazing exercise: Grappling with the slide and its many contributors is arguably the most important ongoing debate in education policy.

In the early 2010s, for example, Goldhaber noted that a “bipartisan consensus around school and teacher accountability” broke down due largely to political exhaustion with former President George W. Bush’s No Child Left Behind policies and then-President Barack Obama’s early embrace of educational reform. Nat Malkus, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and its deputy director for education policy studies, noted the unique nature of the decade prior. “It was a season in American life when it was okay on the left and the right for everybody to just sort of raise expectations,” he told TMD.

By the time the 2013 NAEP was administered, however, that bipartisan push had come to an end. While the precise effects of policies like No Child Left Behind are fiercely debated, the turn away from that program’s quantifiable and standardized education measures has manifested itself in a number of ways. Many selective universities phased out or de-emphasized, for example, the use of standardized tests like the SAT and ACT. Public high schools that used tests to determine admission, like Stuyvesant in New York City and Lowell in San Francisco, became the site of fierce political battles.

Certain pedagogical practices have also been highlighted as a key driver of learning loss. Beginning in the 1990s, for example, many school districts across the country moved away from traditional phonics-based reading instruction, which focused on sounding out words and letters, and toward newer approaches based on vocabulary and context. But a growing body of research suggests that this shift was a mistake, and the pendulum is beginning to swing back. The much-touted “Mississippi miracle” of the past decade, for example, saw the state improve student scores from among the nation’s worst in 2013 to solidly above average by 2024 (this improvement did, however, take place amid an overall decline in student scores). The upswing came after state officials mandated phonics-based instruction, hired reading coaches, and held back third graders if they did not pass a statewide literacy test.

Not every state has made a similar commitment to “getting kids back on track,” as Goldhaber put it, with some still skeptical of standardized testing. In 2022, for example, Washington state superintendent Chris Reykdal said that education observers should “never use a standardized exam to determine whether or not we’re better or worse” in academics, arguing that such tests fail to capture the full picture of student learning.

In many cases, schools are also simply asking less of students. Natalie Wexler, the author of Beyond the Science of Reading, has chronicled how teachers have consistently assigned shorter and shorter reading lists for high school students. Last week, a New York Times survey of 2,000 parents, students, and teachers recorded how teachers increasingly use excerpts, videos, and audiobooks, instead of assigning whole novels. The decline has likely been driven both by standardized tests’ emphasis on analyzing excerpts or short essays and by the belief among some teachers that students simply would not read entire books, Wexler explained. “That comes with a cost. Written language is almost always more complex than spoken language,” she told TMD. Reading whole novels also offers unique benefits. “Sustaining reading over an entire book requires a different kind of cognitive effort,” she said, explaining that it forces readers to follow arguments and juggle characters over many pages.

Finally, broader cultural trends that have little to do with education itself are also likely significant factors. An educational decline beginning sometime in the early 2010s would align well with the widespread adoption of smartphones (the first iPhone was introduced in 2007) and the introduction of electronic devices like Chromebooks into the classroom. Malkus pointed out that evidence of lower standardized test performance among adults, not just children, could indicate that screens and social media reduce cognitive ability and attention spans.

“We always think … it’s got to be the schools, right?” he said. “But then why is it happening to the population of adults?” After all, high schoolers aren’t the only ones trading books for smartphones. Only about 16 percent of Americans read for pleasure on an average day, according to a 2023 study, down from 28 percent in 2004. And overall time spent on screens—be they phones, TVs, or computers—has steadily increased.

Economics may also be a factor. Sean Reardon, a professor at Stanford University’s Graduate School of Education, noted that one reason for the far steeper decline among lower-performing students may be related to the United States’ relatively unequal distribution of school funding among districts. “We’ve always done a good job at providing good educational opportunities to kids in most places,” he said. “We’re just getting worse at providing good opportunities to kids who are not in the most resourced places.”

Lower scores in reading and math, then, have a long list of possible culprits, despite the impulse of politicians to highlight a particular policy or group as at fault. “There’s this inclination to want to be able to point the finger at the smoking gun,” Wyckoff said. “There’s no one solution for this complicated, nuanced problem.”