In the more than five years since Donald Trump and his supporters claimed the 2020 presidential election was stolen, no credible instances of widespread fraud have surfaced. No state or federal court cases have affirmed material fraud or error. And of the many thousands of election administrators who worked the 2020 election, only one has been convicted of a crime: Tina Peters, who is serving a nine-year sentence for unlawfully granting Trump supporters access to voting equipment in Mesa County, Colorado.

Nothing has changed. And yet, in some quarters, the stolen election theory lives on.

This past weekend treated us to another spark of social media excitement as stolen election enthusiasts including Elon Musk (“Massive voting fraud uncovered”), Donald Trump Jr. (“another conspiracy theory proven right!”), and Rudy Giuliani (“Told ya so”) gleefully glommed onto the latest theory of how the 2020 election was stolen (I use the passive voice because the alleged criminals responsible for said theft are rarely named. Doing so results in costly defamation lawsuits, as Giuliani learned to the tune of $148 million).

This round stems from a complaint made to the Georgia State Election Board by Georgia resident David Cross, whose stated passion in life is “exposing and getting rid of Dominion voting machines.” Trump lost Georgia to Joe Biden by fewer than 12,000 votes, and the then-president aimed many of his voting fraud allegations at the state’s election operations.

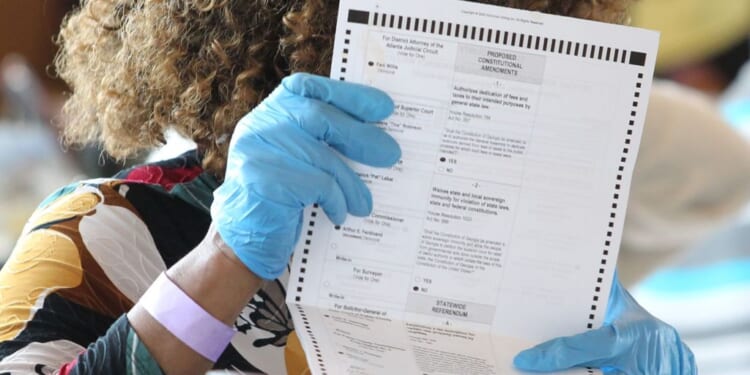

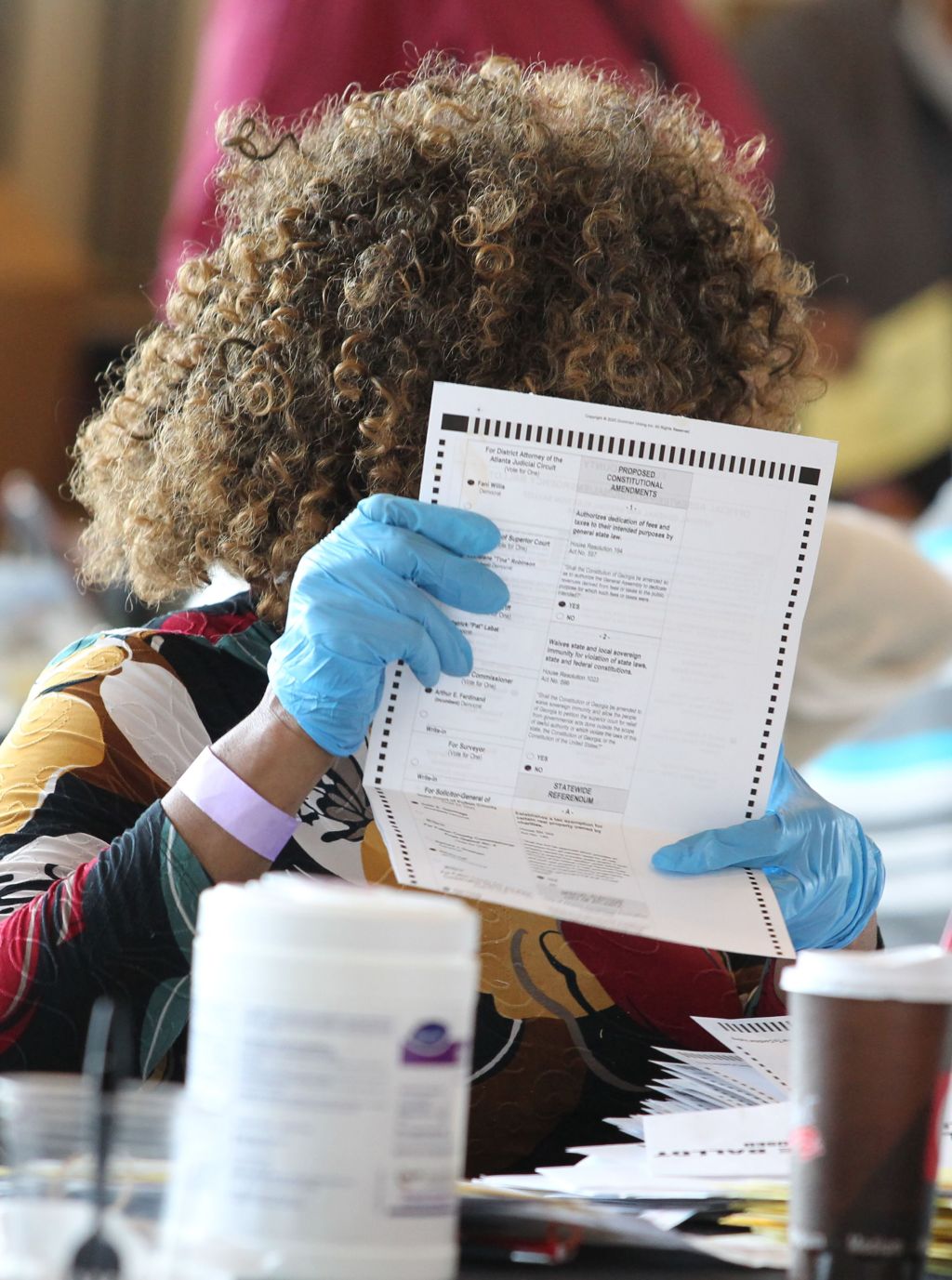

Cross claims that Fulton County officials violated a regulatory rule in its administration of the in-person “advance voting,” or early voting, component of the 2020 presidential election because election workers for the county did not sign a receipt from the setup of each tabulator machine, known as a “zero tape.”

In a hearing on December 9, Fulton County acknowledged the mistake. A subsequent report in The Federalist inaccurately interpreted the county’s admission as meaning “there is no way of telling whether ballots from a previous election (or ballots from a test run) were left on the [scanner’s] memory card … ” Writer Brianna Lyman doesn’t go so far as to allege fraud, but her article —and its headline referencing “315,000 votes”—served as the basis for the resulting social media furor.

Now, this is all a bit wonky and complicated—so much so that both Cross and the State Election Board cited the wrong regulatory rule in Georgia election law. And both reputable media outlets (e.g., Newsweek) and bad-faith actors (e.g., former Department of Justice official Jeffrey Clark, who has been recommended for disbarment for his role in stolen election claims) have mistakenly written that the missing signatures concern the verification of specific voters and ballots.

They do not. Instead, the “zero tape” pertains to the number of ballots tabulated by each scanner.

Let’s step back a bit. To vote in Georgia, voters must first register according to the laws and processes for which the state has been celebrated by the R Street Institute (“Georgia is widely recognized as a leader in election administration”). When at a voting location, the voter must check in on an electronic poll pad. This step is important.

The voter confirms his information and shows identification to an election worker. Only then can the voter make ballot selections on a touchscreen ballot-marking device. When done, the ballot-marking device prints a paper ballot containing the voter’s selections. The voter reviews the paper ballot, makes sure it’s correct, and then the voter feeds that paper ballot into a scanning machine.

That scanner aggregates two counts. First, it reads the results of the voter’s ballot and it adds the voter’s selections to its internal memory card. Second, the scanner adds one ballot to its running total of ballots scanned. That number is visible on the LED screen on the exterior of the scanner.

This second number, the number of ballots scanned, is the number at issue here. During early voting, each time election workers start scanning ballots, and each time election workers end scanning, they add a line to the scanner’s early voting log sheet that contains the total number of ballots scanned. Each time scanning begins anew, the number of ballots scanned should equal the number of ballots when scanning last occurred.

This means that if, during early voting, election workers finished scanning on Thursday night with 10,763 ballots scanned, they should begin tabulating on Friday morning with 10,763 ballots tabulated. The reason for this is obvious: This ensures that nobody has—intentionally or accidentally—tabulated unauthorized ballots or double-tabulated authorized ballots.

The rule governing Georgia’s “advance voting”—183-1-14-.02(7)—doesn’t require that these daily log checks be signed by election workers. It just requires that the “zero tape,” a receipt printed by the scanner at the beginning of the election to confirm that it has so far scanned zero ballots, be signed. This helps to confirm that all results from test ballots or previous elections have been erased.

Fulton County election workers did not sign many of these “zero tapes.” This is what caused The Federalist to claim that “there is no way of telling whether ballots from a previous election (or ballots from a test run) were left on the memory card. … ” But there are multiple other ways of verifying that Fulton County scanners started at zero.

First, as mentioned, to get a ballot, voters must show identification and check in at the voting location. Each voting location keeps a paper tally of the total number of check-ins. If the total number of check-ins is less than the number of ballots scanned at a voting location, then there’s a problem. If the scanners’ memory cards had ballots left over from a test or a previous election, then on the first day of early voting, the scanner would have shown considerably more ballots scanned than voters who checked in that day.

Next, each scanner itself has an internal digital log that shows when any action takes place, including the scanning of ballots. Any allegation that a scanner didn’t start at zero, or scanned ballots at an unauthorized time, could be revealed by the digital log.

Additionally, Georgia releases a daily list of the names of voters who have cast an early ballot. This allows voters to confirm their ballots were counted and candidates and political parties to know who has already voted. If the number of people who had voted at an early voting location did not match the number of ballots scanned at a location, this would reveal something amiss.

Due to the narrow margin in the presidential election, the Georgia secretary of state did both a hand count audit of the vote and, at the request of the Trump campaign, a full recount of the vote in November 2020. If Fulton County had scanned test ballots, ballots from a previous election, or if the county had double-counted certain ballots, the recount would have revealed those discrepancies. But no such discrepancy surfaced.

So did Fulton County election workers fail to sign some early voting “zero sheets”? Yes. Did that failure cause a problem so major that any court in the United States would throw out the votes of 315,000 Georgians because of it, as David Cross requested? No.

Both state and federal election law holds that courts should avoid punishing voters for the mistakes of election workers (see, for example, the Georgia Supreme Court’s 2013 ruling in Meade v. Williamson). Election professionals, the Associated Press, and others explained all of the above in 2023 in response to a different complaint. But hope springs eternal for the fraud-seekers.

Following the hearing on Cross’ complaint, the Georgia State Election Board has referred the matter to the state attorney general. I suspect the AG’s investigators will find that some election workers simply forgot their training. This was, after all, an election held in the midst of the COVID pandemic, which made recruiting election workers harder and training times shorter. And this was Georgia’s first election cycle using paper ballots (it used direct-recording electronic voting machines in 2016 and 2018).

If Attorney General Chris Carr, a Republican, finds Fulton County broke election rules, the county could be assessed a fine. And the matter already has resulted in changes to Fulton County’s practices. Fulton County’s attorney stated at the December 9 hearing that “since

2020, we have new leadership … new standard operating procedures; the training has been

enhanced; the poll workers are trained [on this] specifically.”

The situation revealed fallibility in the human beings administering elections in 2020 in Fulton County. Such fallibility was likely present in other counties in Georgia, and other jurisdictions in the United States. State Election Board member Janelle King made this point in her remarks at the December 9 hearing, and this reveals one of the ironies of Cross’ complaint, and of other similar complaints. Yes, Cross found an instance in which humans made a mistake. His solution? “Hand-counted paper ballots, counted by human beings, not computers,” he said at the hearing.

Somehow, I don’t think the answer to human error is to task humans in future elections with counting hundreds of millions of ovals marked on ballots.