When the Berlin Wall crumbled in 1989 and the Soviet Union dissolved two years later, a great many in the West declared the long struggle settled. The free market had prevailed, liberal democracy stood unchallenged, and the century-long duel between Marx’s prophecy and humanity’s stubborn pluralism seemed finally resolved.

Yet, China’s extraordinary rise in the 21st century revived a confidence many assumed had died with the USSR. The Marxist system—a model of society so discredited that only museum shelves and the occasional graduate seminar would remember it—seemed to wear the face of a global power again, and the world slipped back into a bipolar posture. But the front lines of this new cold war run not just between nations, but through the interior of Western societies themselves. Cultural rifts at home now refract foreign policy abroad, turning geopolitics into another theater of the culture wars.

How else to understand the spectacle of MAGA firebrand Tucker Carlson, who recently commended Nicolás Maduro—a socialist strongman who presides over economic ruin and state repression—solely because he banned pornography, abortion, gay marriage, and gender transitions? In Carlson’s framing, Venezuela became “one of the most conservative countries in North or South or Central America,” and the U.S.-aligned opposition was cast as “pretty eager to get gay marriage” into Caracas, as though the crisis of Venezuelan democracy were simply another skirmish in America’s own cultural trench warfare.

The pattern repeats on the other pole of the ideological spectrum. Progressive commentator Hasan Piker toured China and lauded the achievements of the Chinese Communist Party while gliding past the imprisonment of dissidents, the suffocation of civil society, and the machinery of surveillance that touches every corner of Chinese life.

For the right, economic repression becomes tolerable so long as a foreign regime strikes the proper blows against any marker of modern liberalism they despise. For those on the left, they can wave away social coercion because they admire the scale of the welfare state or the mirage of “efficient” central planning. Each camp selects the pieces that flatter its priors and discards the rest. What emerges is not analysis but projection—foreign governments turned into cardboard stand-ins for domestic grievances, avatars drafted into America’s never-ending feud with itself.

Growing up where communist rule wasn’t an intellectual exercise but a scar still raw in national memory, I learned early that the ideology so many Westerners romanticize bears no resemblance to the clean abstractions they parse in classrooms or on Twitter threads. Communism is not socially conservative in the way American traditionalists imagine, nor is it economically liberatory in the way Western progressives sometimes pretend. Those who invoke it as a convenient prop in America’s culture wars reveal, most of all, the distance between their rhetoric and the realities they presume to interpret.

Consider a recent example. On the Triggernometry podcast, Piker remarked, “While I don’t call myself a communist, I don’t have an issue with the end goal of communism. … I just think that it’s probably not likely to happen. A stateless, moneyless, borderless society … I think that communism would be most likely an international thing. It’d be like the Star Trek universe. And it feels especially at this point far too utopian to achieve.”

To him, the problem with communism isn’t its premises but its feasibility, because it imagines a postscarcity federation of enlightened citizens—a vision so frictionless it belongs more to science fiction than to political reality.

When host Konstantin Kisin noted he had been born in the USSR and did not share that optimism about communism, Piker replied that the Soviet Union had merely attempted communism without achieving the genuine article: “They never actually were able to successfully implement communism. It wasn’t a borderless, moneyless, classless society.”

The trouble with this formulation is that it treats the gap between theory and practice as a bureaucratic inconvenience rather than the central tragedy of the ideology itself. If perfection is always just out of reach, then every failure can be excused, every cruelty reframed as an unfortunate detour on the road to the earthly paradise.

But there is a place in recent history that came closer to fulfilling the ideological parameters Piker outlined than the USSR ever did—my birthplace, Cambodia. Or rather, Democratic Kampuchea, the regime that ruled from 1975 to 1979 under Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge.

“What came out of that experiment was not human flourishing, but the annihilation of every fragile, humane instinct that keeps a society recognizable to itself.”

If one seeks a society with no money, no private property, no markets, no borders as an expressive category, and no class distinctions beyond the party’s revolutionary vanguard, Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge is the bleak prototype. Khieu Samphan, who served as head of state of Democratic Kampuchea, once summarized the ideology:

The moment you allow private property, one person will have a little more, another a little less, and then they are no longer equal. But if you have nothing—zero for him and zero for you—that is true equality.

While the second article of the Constitution of Democratic Kampuchea used more moderate language—“property for everyday use remains in private hands”—the Khmer Rouge took the elimination of private ownership to its logical extreme, forcing citizens to surrender everything but a few personal scraps. The real governing ethos appeared not in the constitutional text but in the slogans that had already circulated through the “liberated zones” of the countryside in the years before 1975. As provincial towns fell and cooperative life was imposed, a new orthodoxy took hold: “All that every Cambodian has the right to own is a small bundle he can carry on his back,” and the even more chilling dictum, “Absolutely everything belongs to the Angkar [the secretive ruling body of the Khmer Rouge].”

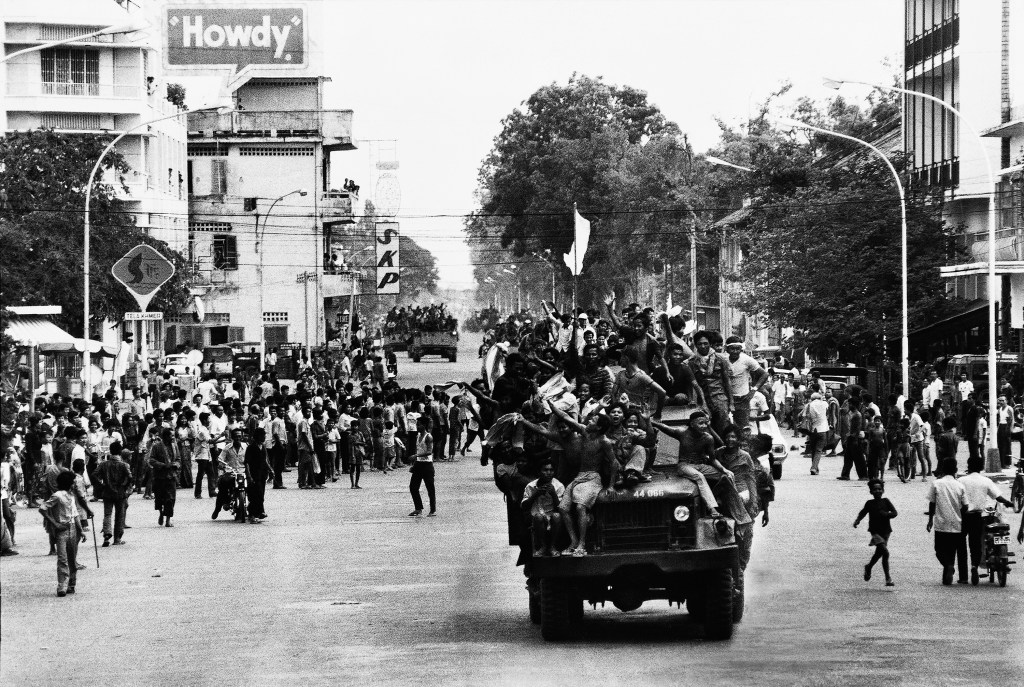

On April 17, 1975—the day Phnom Penh fell to the Khmer Rouge—this philosophy was enforced on the last major urban population, extending a project that had until then remained regional to the entire country. Within hours, the capital was emptied, its inhabitants forced into the countryside at gunpoint. Urban life, in the party’s cosmology, was a bourgeois infection, a softening agent that threatened the revolutionary core. To cleanse it, the Khmer Rouge did not merely reorganize society; they uprooted it. Hospitals, schools, and monasteries were evacuated on the spot. Newborns were carried into the heat, the wounded wheeled away on hospital beds, the elderly compelled to march until they collapsed. A nation was made nomadic overnight.

Currency vanished next. With a single decree, every banknote—from the riel to the emergency coupons circulating in the capital—was declared void. Families who had spent years saving for medicine, education, or simple security found their wealth reduced to colored paper. Exchanges of any kind were forbidden; markets were stamped out; even bartering became suspect. A society built on rice harvests, trade routes, and regional commerce was overnight driven into subsistence units under absolute state authority.

The idea behind this abolition was neither accidental nor uniquely Cambodian. It drew on a purist reading of Marxist theory, one that sought to bypass the capitalist stage altogether and leap directly into a classless agrarian millennium. Where others hesitated, Pol Pot and his circle pressed forward. The Bolsheviks tried, briefly and unsuccessfully, to build a nonmonetary economy. China’s radical wing voiced similar ambitions during the Great Leap Forward, and Cuba toyed with the idea before retreating to more conventional socialist management. But only in Cambodia did a ruling party attempt to erase money itself.

Andrew C. Mertha, a leading scholar of Chinese and Cambodian politics, called this a “literalist interpretation of communism,” and the description is apt. The leadership of the Khmer Rouge did not see Marx as a springboard but as a blueprint. If Marx wrote of a society without currency, then the revolution must sweep away currency. If Marx imagined a world without class distinctions, then class must be extinguished through forced reeducation, surveillance, and, when necessary, liquidation. If Marx spoke of internationalism, then borders themselves had to become secondary to the ideological orthodoxy of the revolution.

In a speech titled “Long Live the 17th Anniversary of the Communist Party of Kampuchea,” delivered on September 29, 1977, Pol Pot celebrated the abolition of currency as proof of ideological triumph:

We continue to operate without the use of money, with no daily salary. Our entire people, our Revolutionary Army, all our cadres and all our fighters live in a collective system through a communal support system, which is being improved with every passing day. This is a successful step toward the solution of the contradictions between the cities and the countryside, between the workers and the peasants, between manual workers and intellectuals, between the cadres and the masses, between the economic infrastructure and the superstructure.

Here was communism articulated not as a distant aspiration but as a lived reality, proclaimed by its architects at the height of their power. The regime’s leaders believed, sincerely and disastrously, that they had done what others could not: eradicated class contradiction by extirpating the social categories that produced them. In their doctrine, the absence of money was not an administrative detail—it was the revolutionary solvent through which all lingering inequalities would dissipate.

Pol Pot described the communal system as if the nation had seamlessly ascended into a harmonious equality. But beneath that triumphal rhetoric lay a more brutal truth: Those “contradictions” were resolved not through consensus or abundance but through forced labor, mass displacement, and the grinding deprivation of a people denied every economic mechanism that sustains life.

What came out of that experiment was not human flourishing, but the annihilation of every fragile, humane instinct that keeps a society recognizable to itself. To speak of communism as a noble destination sabotaged by flawed travelers is to ignore this, because the Marxist ideal—whether labeled socialism or communism—hinges on redistribution. And redistribution, however elegantly phrased in theory, always demands a steward, an allocator. It calls forth a managerial class even in a system that vows to extinguish class itself.

Once a society pulls economic power away from its citizens and concentrates it in the hands of those stewards, the result follows a grim pattern. Power corrupts; the authority to distribute life’s necessities corrupts even faster. Absolute control over redistribution becomes its own ideology, one that tolerates no rivals and requires ever-tighter enforcement to sustain itself. Good intentions cannot restrain such a system. Individual virtue cannot redeem it. A society should never have to gamble on the hope that the people at the top will resist the temptations that come with unbounded discretion.

That is the core flaw embedded in the dream Piker describes—a stateless, postscarcity brotherhood where human nature has been perfected into something predictable and benign. Year Zero Cambodia revealed the opposite truth. When the Khmer Rouge abolished money, markets, borders, and private property, they did not eliminate the struggle for advantage; they consolidated it. The Angkar became the fountainhead of all permissions. Food, medicine, movement, marriage, labor—every decision was routed through the revolutionary center. And when one group holds exclusive dominion over the distribution of survival itself, the word “equality” becomes a rhetorical ornament.

The tragedy is that this dynamic is not unique to Cambodia. Variations of it recur wherever redistribution becomes the organizing principle of a society. A system that imagines itself morally immaculate tends to rationalize the harshest measures in the name of maintaining that immaculate state. And the further it drifts from lived reality, the more ruthlessly it must discipline its citizens to preserve the illusion.

Some Western commentators approach these ideologies as though they are blank canvases waiting for the right visionary to complete them. They imagine that with better leadership, more humane incentives, or a purer interpretation of Marx, the next attempt might redeem the project. But the Khmer Rouge were not incompetent amateurs bungling a utopian script. They pursued the script with greater fidelity than any regime before them. Their failure was instructive. They exposed the hazard of letting a theory that romanticizes total equality become a guide for governing real human beings with real needs, fears, imperfections, and loyalties.

But the Khmer Rouge’s experiment wasn’t confined to the economic realm. The same ideology that sought to erase markets also attempted to purify the human spirit, and in doing so constructed one of the most aggressively puritanical social orders of the modern era. In much Western popular commentary, communism is treated as socially emancipatory—a kind of collectivist progressivism scaled up to the level of the state. But for all their Marxist rhetoric, the revolutionaries who claimed to be building a classless tomorrow for Cambodia governed their subjects with the moral rigidity of an ancient priesthood.

Consider how the Khmer Rouge treated marriage and family formation. If the family existed to serve the revolution, then the revolution was entitled to define what a family was. Marriage ceased to be a covenant between households; it became a cog in the machinery of national purification. As the party’s youth magazine Revolutionary Youth put it,

Therefore, in order that our families may know true happiness, peace, and prosperity, our entire nation and people must first be liberated and freed from every type of exploitation by the reactionary imperialists-feudalists-capitalists. So, building our revolutionary families is not just for our personal interests or happiness, or to have children and grandchildren to continue the family line. Importantly, it is so that the revolution may achieve its highest mission, to liberate the nation, the people, and the poor class and then advance toward socialism and communism.

Traditionally, Khmer society entrusted marriages to elders. Mothers, aunts, and village matrons negotiated unions. An achar—a Buddhist priest—would be consulted to judge compatibility and choose an auspicious date. These were not merely transactions but fusions of kinship networks, ritual, and the tacit wisdom of people who understood village life down to its emotional grain. The Khmer Rouge looked at these customs and saw only corruption. If elders guided matches, class interest guided elders. And if love was involved at all, it was suspect—an indulgence that might distract from the revolution’s higher purpose. The solution was the same one applied to every other facet of life under Democratic Kampuchea: replace the organic with the engineered.

Thus, the party assumed the role traditionally held by families, monks, and matchmakers. “When marrying,” Revolutionary Youth instructed, “it is imperative to honestly make proposals to the Angkar, to the collective, to have them help sort things out.” In theory, young men and women could choose their partners. In practice, no union existed until it had been sanctified through bureaucratic approval.

What followed was a system in which couples were paired in mass ceremonies, matched not for compatibility but for political reliability. Husbands and wives learned each other’s names on their wedding day. They stood before officials, not elders. They pledged themselves to the revolution first, each other second, if at all. Many were coerced into consummating marriages they never chose—acts carried out under duress and stripped of agency. Gay men and lesbian women were not spared in these rituals. The Angkar made no allowance for orientation; it did not even acknowledge that such a category existed. Those whom their villages quietly understood to prefer the same sex were compelled into heterosexual unions with strangers, and refusal was treated as sabotage.

“If the family existed to serve the revolution, then the revolution was entitled to define what a family was. Marriage ceased to be a covenant between households; it became a cog in the machinery of national purification.”

In the sprawling imagination of the Khmer Rouge, cities themselves were sites of moral decay—places where softness, individuality, and cosmopolitan habits had infected the national spirit. Phnom Penh was a moral failing. By emptying it, the regime believed it was returning a corrupted people to a purer origin, a rural Eden that had supposedly existed before markets, music, literature, and the clutter of human difference. Their utopia was not futuristic at all. It was a reactionary dream of enforced simplicity—a society stripped to pre-modern austerity, policed by revolutionary monks.

In recalling the seizure of Phnom Penh, Pol Pot stated:

The brother and sister combatants of the revolutionary army … sons and daughters of our workers and peasants … were taken aback by the overwhelming, unspeakable sight of long-haired men and youngsters wearing bizarre clothing making themselves indistinguishable from the fair sex. … Our traditional mentality, mores, traditions and literature and arts, and culture and tradition were totally destroyed by U.S. imperialism and its stooges. … Our people’s traditionally clean, sound characteristics and essence were completely absent and abandoned, replaced by imperialistic, pornographic, shameless, perverted, and fanatic traits.

One need not stretch far to recognize the danger in the way some Western voices look at foreign authoritarianism through a keyhole, focusing only on the parts that flatter their resentments at home. When Tucker Carlson applauds Nicolás Maduro for banning pornography, abortion, and same-sex marriage, he reveals a temptation older than the Cold War: the wish to outsource one’s moral agenda to any strongman who promises to deliver it. The fact that Maduro presides over shortages, corruption, and repression becomes irrelevant so long as he wages the right kind of kulturkampf.

If such observers were to evaluate the Khmer Rouge through the same narrow lens, what would they see? A regime that outlawed divorce, enforced sexual chastity, punished extramarital relationships with execution, segregated men and women into rigid labor divisions, and imagined itself as the guardian of an embattled national virtue. A movement that distrusted art, discouraged pleasure, and treated individuality as a subversive impulse. A government that replaced the family with the state and demanded obedience not only of behavior but of thought.

Would some of today’s culture warriors mistake that severity for strength? Would they praise the discipline while overlooking the cruelty, just as their counterparts on the left admire social equality while averting their gaze from the camps? It is not a hypothetical meant to draw glib equivalence. It is a reminder that authoritarianism often wears the costume of moral clarity. And when people become so consumed by their domestic feuds that they begin to valorize foreign tyrannies for banning the sins they dislike, they reveal something troubling about their own political appetite.

The tragedy of Cambodia is that its revolution fused the worst impulses of both ideological poles: the economic absolutism of the radical left with the moral absolutism of the radical right. It built a world with no money and no markets, but also no music, no private affection, no family autonomy, and no room for the ungoverned rhythms of human life. It was the nightmare that emerges when purity—of class or of culture—is pursued with equal fanaticism.

And if the West persists in grafting its fantasies onto distant regimes, mistaking repression for order or coercion for virtue, it risks learning the lesson only after stepping too close to the edge: that utopias, whether painted red or draped in traditionalist rhetoric, demand the same sacrifice at the altar of perfection—the human being, made small enough to govern.