Immediately after the January 3 military raid on Venezuela that extracted that South American country’s president, Nicolás Maduro, and spirited him to New York to stand trial for drug charges, the media sought historical parallels. The obvious one was the similar “arrest”—assisted by 27,000 American troops—of Panama’s leader, Manuel Noriega, a remarkable 36 years earlier to the day. U.S. prosecutors had also indicted Noriega on drug charges, and he spent the rest of his life in U.S., French, and Panamanian prisons, dying in 2017.

But Panama offers a misleading parallel. The tiny republic was flanked by U.S. troops in the Panama Canal Zone, which made it easy to overwhelm and occupy. It had a long history of democracy, which almost everyone but Noriega was eager to return to. And Noriega had declared war on the United States.

Instead of 36 years back, therefore, let us consider the parallels—and pitfalls—of military intervention in Latin America that become clearer if we go back a full century. In 1926, the United States government was decades deep into unfurling a more offensive, preventive version of the Monroe Doctrine.

A century before that, in 1823, the fifth president had declared that the United States would oppose any further colonization of the Western Hemisphere’s republics by extra-hemispheric powers. The warning was aimed squarely at Europeans who might be tempted to move on Latin American countries newly freed from Spain’s clutches. Europeans said nothing, independence proceeded largely unimpeded, and most forgot about Monroe’s message.

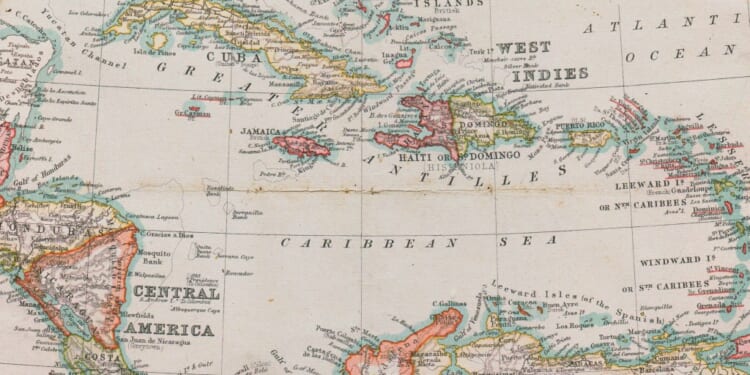

In 1904, President Theodore Roosevelt announced what would become his namesake “corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine: that the United States would no longer react to any European re-colonization but would instead now prevent any hint of such by exercising an “international police power” in Central America and the Caribbean. Roosevelt and his “big stick” embodied the new imperial image of a cop on the beat, keeping the “neighborhood” safe from outside agitators.

The Roosevelt Corollary meant a permanent U.S. military presence in the Caribbean Basin: naval bases, frequent landings of Marine gunboats, and the defense of the Panama Canal, the construction of which began that same year and which would open 10 years later, just as the Great War ratcheted up fears of German meddling in the area. The corollary also meant greater U.S. financial imperialism, usually in the form of Wall Street loans to pay off delinquent European ones taken out by often-unscrupulous dictators. The State Department then ordered the Marines to oversee receiverships over small, poor governments to make sure Wall Street was paid back. In that context, from 1901 to 1934, American presidents ended up running—or advising with a heavy hand—many countries of the region, and often through formal “agreements” designed and imposed at the point of bayonets, the same way the Trump administration has said it plans to “run” Venezuela by threatening further military action.

By 1926, therefore, Washington wielded imperialistic power over a dozen nations in its neighborhood. In Cuba, for instance, it used the Platt Amendment to control the island’s treaties, bases, and more. (In 1926, Washington had already ended three military interventions since just 1898.) In Panama, the United States enjoyed a treaty from 1903 that “protected” the new nation in return for a U.S. right of intervention—last invoked in 1925. In early 1926, the Marines in Nicaragua were transitioning from a 100-man occupation force to one that would grow to thousands as it met resistance from guerrilla leader Augusto Sandino. In the Dominican Republic, the Marines had left in 1924 after an eight-year military government helmed by U.S. rear admirals, but that occupation had created a national police force that its commander, Rafael Trujillo, would soon use to install himself as an iron-fisted dictator and hold power until 1961. In Haiti, finally, 1926 was around the middle of a brutal 19-year military occupation; the Marines would remain until 1934, leaving only under pressure from the White House.

A hundred years ago, then, the U.S. government had not yet learned that military occupations in Latin America are hugely unpopular with locals and especially non-occupied Latin Americans and tend to fail in their intentions.

One pattern that occupation officials failed to discern early enough is that, while locals sometimes accepted and even welcomed the fact of occupation by a foreign power, those same locals would almost invariably resent the manner of occupation once it settled in. A book I published a dozen years ago is newly relevant for imparting this lesson. Whether in Port-au-Prince, Santo Domingo, Havana, or Managua, there were always some Latin Americans who saw the landing of a U.S. force as cleansing. These are the soldiers of a democracy. Surely they will rid us of our corrupt leaders and usher us into a similar democracy. “We do not want American intervention,” said one Dominican as he witnessed Marines disembarking on his shores in 1916, “but with each of our revolutions, we do nothing but invite it.”

Over the following months and years, Dominicans and others lost their illusions that Americans would usher in rapid political and economic change. They realized that they really did not want American intervention. For one, Americans immediately came for their guns—and Latin Americans, humiliated, engaged in firefights to keep them, notably in a series of battles in 1916 in Santo Domingo. What occupied peoples complained about most, however, was the brutality that almost always accompanies a foreign occupying force. “Where troops have been quartered,” warned Chinese philosopher Laozi thousands of years ago, “brambles and thorns spring up.”

Those thorns came in the form of newspaper censorship, soldiers who fought with and raped locals, and harsh sentences handed down for minor offenses. Some Marines, allowed to police small, unarmed towns with impunity, unleashed abuses that locals recalled well into the 1970s. “Who was going to talk back to those despots if they ruled?” complained one Nicaraguan of the American “liberators.” “They killed whomever, and they killed for pleasure.”

U.S. occupiers also took private property, whether commandeering a horse, slaughtering a pig, displacing whole villages to make way for sugar factories in the Dominican Republic, or rewriting the Haitian constitution to allow foreigners to purchase land. In short, their actions served as a poor advertisement for the “land of the free.”

The behavior of occupiers, therefore, often dashed the hopes of those who expected material progress, if not democracy. Add to this disillusion the unintended consequences of occupation: While the U.S. built roads, railroads, and telegraph networks with the aim of helping local inhabitants bring their agricultural goods to market, this infrastructure enabled would-be despots to crush any internal opposition.

A second pattern of occupations that might not be intuitive—but makes sense—is that they do not bring out the best in the people under occupation, either. Why should they? Why should we expect people to be heroic or self-sacrificing when repressed and frustrated?

When occupying forces landed in Latin America, they threatened not just dictators. They also angered educated Latin Americans who had jobs in government when legislatures were dissolved, as in Haiti in 1917, or suspended, as in the Dominican Republic in 1916. Those suddenly on the outs turned to the resistance tactics of the weak—disobedience and sabotage. Some organized public protests, then more protests when the Marines jailed them for protesting. Some journalists, frustrated by censorship, made up scandals to pressure the Marines to leave. Some headed to the mountains to form anti-occupation guerrillas.

The irony? Occupations with such goals as ending cycles of revolution and teaching responsible self-government—especially given Woodrow Wilson’s ambition to make the world “safe for democracy”—ended up infantilizing the natives and keeping them from solving their own problems. In 1930, one prominent Haitian complained to visiting Americans, “We have now less knowledge of self-government than we had in 1915 [when occupation began] because we have lost the practice of making our own decisions.” To the same Americans, a group of Haitians added, adopting Wilson’s English term: “There is only one school of self-government, it is the practice of self-government.”

The takeaway of occupations in Latin America was that the people living under them learned to doubt the promises of Americans. Instead, they banded together to denounce abuses and unintended consequences. They found allies in larger Latin American capitals, Europe, and the Congress (which in 1932 cut off funding to the Marines occupying Nicaragua) to put an end to an imperial era that had achieved little of what it had sought. In the 1930s, Franklin Roosevelt’s administration finally agreed on the principle of non-intervention, and so began the more peaceful Good Neighbor era.

The Trump administration’s might-makes-right imperialism now on display in Venezuela—and perhaps soon elsewhere—is a historically myopic and potentially cataclysmic error. If left unchecked, it will set back the progress made against imperialism by a full century.