The American writer Stewart Brand occupies a spot at the intersection of hippie and futurist. He created the Whole Earth Catalog, a countercultural magazine that Steve Jobs later compared to “a sort of Google in paperback form, before Google came along.” He helped launch the All Species Foundation, which sought to catalog every type of living thing on earth. He’s the subject of a documentary called We Are As Gods, which focuses on his fight to bring back extinct species.

He is also the founder of the Long Now Foundation, which aims to build a clock that will keep time for 10 millennia with minimal human help. But his newest book, Maintenance of Everything, Part One, lies at the other end of the spectrum of how we interface with our machines. Brand wants to minimize maintenance needs for the Clock of the Long Now, so it has a chance of lasting long into the future, even if humans don’t. But, at the scale of a human life, he doesn’t see maintenance as something to delegate away. Maintenance, to Brand, is a way of keeping faith with the world and with each other. Everything we build is slowly deteriorating from the moment it leaves our hands. Maintenance is the patient art of opposing entropy.

It’s easy to experience maintenance as drudgery. Every day, my husband and I maintain our toddler by offering him cereal, 70 percent of which winds up on the floor. I then maintain our house by sweeping up and maintain my character (I hope) by patiently and warmly offering the cereal again the next day. Brand has a warm appreciation for this kind of faithful service: Although this work may feel invisible and undervalued, Brand makes it clear that when the stakes are highest, smart leaders put maintenance first.

Many of Brand’s examples are drawn from military applications, where one errant detail can spell disaster. In 1973, Egypt lost its October War with Israel despite early victories, in part because its army had no habit of tank maintenance and repair. Of the 840 Israeli tanks that were disabled in the fighting, half returned to service before the conflict was over. On the Egyptian side, 80 percent of the tanks broke down in the first 10 days, and many were abandoned on the battlefield because Egypt did not recover and repair them. Instead, Israeli forces captured, repaired, and redeployed about 300 Egyptian tanks against their former operators.

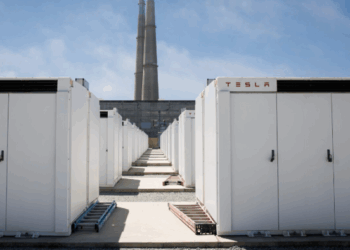

As Brand argues, maintenance isn’t just a matter of taking care of the object before you. It begins with the design of the object, so that it is oriented toward sustainable maintenance for its entire useful life. That might mean mounting the tool you need to unjam a rifle on the rifle so it’s near when a soldier needs it. (As Brand explains, the AK-47s used by the Viet Cong had this feature, but the “advanced” M16 used by Americans had a collapsible tool that couldn’t be reassembled easily in the middle of battle.) It can mean deskilling maintenance, so it doesn’t take a craftsman to install a spare part.

In France in 1785, Honoré Blanc performed a feat of anticipatory maintenance that looked like a magic trick. At that time, rifle parts were filed to fit together individually. When a piece broke, the whole rifle needed to be taken to a gunsmith, behind the front lines, so he could make a new part specific to the individual rifle. Blanc developed a system for making easily changeable parts, with technicians using jigs to exactly reproduce a master form. Gunsmiths didn’t like being reduced to mere copyists, rather than artisans, but the results were inarguable.

In front of a group of dignitaries (including Thomas Jefferson), Blanc disassembled 25 guns made according to his design. He placed each part in a box (25 triggers, 25 hammers, etc) and shook the boxes till the pieces were jumbled together. Then, without hesitation or friction, he reassembled 25 guns from the pieces before him. Each was ready to fire.

The effect of this demonstration reminds me of the bloodless and total military victory won in the year 301 by the minor-Chinese-official-turned-warlord Yu Gun. When bandits menaced his region, he formed his men up in orderly ranks, at a time when fighting in formation was rare. The sight of his men, unified and obedient to order, was enough to make the bandits scatter and flee.

Maintenance often begins with standardization, regularity, simplification, and interchangeability. What would it take to be able to pop off the broken part of a machine and replace it quickly? How many pieces and processes are really necessary to achieve the result you’re aiming for? Brand contrasts the bespoke perfection of early (and expensive) Rolls-Royces, which could run for ages without any part failing, with the scrappy DIY spirit of the Ford Model T, which was cheaper and had a higher failure rate but could be repaired (and customized) by almost anyone.

One of the fun parts about Maintenance of Everything, Part One is that Brand seems to be using the book’s form as a way to explore his own ideas: Despite the rise of e-readers and chatbots, no one has yet improved on the book as a form of communication. In Maintenance Of Everything, Part One, Brand doesn’t succeed either, but he has a lot of fun trying. (And the reader will, too.) Brand has been slowly workshopping his book in public through a special site designed by Works in Progress. Chapters go up sporadically, and readers can suggest corroborating sources or spark a disagreement in the margins. In the first printed volume of Maintenance of Everything—which is what I’m reviewing here—these conversations are included. The book (a beautiful object, like everything from Stripe Press) comes pre-scribbled with marginalia—hat tips to commenters, suggestions for future readings, the story of securing rights to an alternate photo when one source declined. And there’s plenty of whitespace for readers to add their own notes.

Given this genesis, it’s not a surprise that the book has both the flaws and delights of a late-night conversation with a passionate friend. A look at the table of contents is warning enough. The book comprises two chapters: a tightly written first chapter on the 1968 Sunday Times Golden Globe Race (that sent sailboats to circumnavigate the world), and a sprawling second chapter “Vehicles (And Weapons),” that includes five enumerated digressions and two postscripts. It is weaker than the first chapter, but my copy still wound up studded with dog ears, and I put Brand’s book down for two weeks while reading the first of several library holds I placed based on his citations and readers’ marginalia.

As Brand and Stripe collaborate on future volumes, I hope they also print the first chapter as a sort of nonfiction novella. In the Golden Globe race, one sailor wanted to build the perfect sailboat, with customized, fiddly electronics. Another competitor spent at least three hours a day on repairs. Another tried to plan for sustainable maintenance by simplifying everything on the ship, so that repairs would be minimal. In no particular order, one man claimed the prize, one man killed himself, and one elected to leave the competition rather than return to shore.

How we approach maintenance determines what and who we feel able to commit to caring for. The careful examples of Maintenance of Everything offer a guide to how to live life sustainably and generously, by planning from the start how to keep faith till the end.

Stewart Brand is 87 years old. He has uploaded a third chapter of Maintenance of Everything to his collaborative site, but I do not know if I should expect a full Part Two (or how many digressions it would include). But it would make sense, given his life’s work, to entrust a structure (physical or philosophical) to the next set of inhabitants, to keep it alive by letting it grow and evolve. I’ll try to do my bit.