You’re reading Dispatch Culture, our new weekly newsletter exploring the world beyond politics. To unlock all of our stories, podcasts, community benefits, and our newest feature, Dispatch Voiced, which allows you to listen to our written stories in your own podcast feed, join The Dispatch as a paying member.

This weekend, we’re focusing on books. Dispatch Contributing Writer Leah Libresco Sargeant—who also recently published a book—has reviewed a unique little tome called Maintenance of Everything, Part 1, written by hippie futurist Steward Brand. “The book comprises two chapters: a tightly written first chapter on the 1968 Sunday Times Golden Globe Race (that sent sailboats to circumnavigate the world), and a sprawling second chapter ‘Vehicles (And Weapons),’ that includes five enumerated digressions and two postscripts,” Libresco Sargeant writes. “It is weaker than the first chapter, but my copy still wound up studded with dog ears, and I put Brand’s book down for two weeks while reading the first of several library holds I placed based on his citations and readers’ marginalia.”

Meanwhile, the radio show host and writer Leigh Snead has shared with us an adapted excerpt of her forthcoming book Infertile but Fruitful: Finding Fulfillment When You Can’t Conceive, which will be published by Sophia Institute Press on January 20. In the book, Snead writes about her and her husband’s decision to grow their family via adoption. “I’ve known many couples who have struggled with infertility to hesitate before jumping into adoption,” Snead writes. “I am sure that, for a lot of them, simply investigating the adoption option feels like a kind of letting go of the biological children they had dreamed of welcoming into their family. … In short, they may feel like they’ve given up, like they’ve quit, like they’ve admitted defeat.”

Earlier in the week, Dispatch Editor-in-Chief Jonah Goldberg wrote on the warlike tone of the Trump administration’s communications—and the overall twisting of patriotic sentiment into “fascistic propaganda—and congressional reporter Charles Hilu covered a bill that would significantly limit who is allowed to pursue surrogacy in the United States. And, an audio bonus: Steve Hayes and I chatted on The Dispatch Podcast about the impetus behind this newsletter and our plans for it going forward. That’s all!

Have you tried Dispatch Voiced?

Our newest members-only feature makes it easy to listen to our journalism on the go. Listen to high-quality audio versions of our biggest stories in your podcast player of choice, and catch up while grocery shopping, commuting to the office, running at the gym, or walking the dog.

American Artifacts

A Force of Nature—and His Tour de Force

Pop music dominated the charts in 1983, and the top pop artists dominated pop culture. It was the year of Michael Jackson, Prince, Cyndi Lauper, Lionel Richie, and Culture Club. In late July, The Police’s juggernaut “Synchronicity” was the No. 1 album, and its ubiquitous ballad “Every Breath You Take” was the No. 1 single. The same week, Madonna released her first album.

There was absolutely no reason to expect that, in that very same week, the greatest American blues guitarist of all time would record a live concert in a small club in Toronto that would go down as the greatest album of America’s foundational form of music.

Stevie Ray Vaughan, who passed away in 1990, was a force of nature. His Live at the El Mocambo is a tour de force.

Vaughan, known as “SRV,” has mythic status in blues circles. His singing voice was strong, gritty, and had an unusually wide range for the genre. His songwriting was very good, his tiny band excellent. But his guitar chops were unfathomable. He is carved—alongside Eddie Van Halen, Jimi Hendrix, and Duane Allman—into the Mount Rushmore of American guitarists. England’s Eric Clapton said no one commanded his respect more than SRV. More recently, contemporary guitar wizard John Mayer inducted SRV into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, saying, “Stevie Ray Vaughan is the ultimate guitar hero.”

SRV’s fretboard speed was staggering. But he didn’t fly soullessly through scales and arpeggios like a 1980s hair metalist. Instead, he knew all the licks of his predecessors, internalized the sound of the blues, and never got seduced by fancier forms like jazz or classical. The result was an improvisational style that was often inventive but always authentic.

The entirety of Live at the El Mocambo is just 63 minutes. It’s the length of a punk show. Similarly minimalist is the stage. The band is merely SRV and his drummer and bassist. No keyboard, no horns, no second guitar. There are some amps, a microphone, and a few drinks. He uses no showy guitar effects, just a little wah-wah. He has no dancers, no pyro, no orchestra. The setlist is just 12 songs.

As a rule, musicians’ style is faddish. If you saw Madonna’s mesh top and bracelets, Cyndi Lauper’s pastels and asymmetric coif, or Boy George’s hats and jackets, you’d know it was 1983 even before you heard their synths. But SRV’s look and music were indifferent to the times. He wore a patterned, open-neck, silk-ish shirt; a variety of tribal necklaces; a bandana around his neck; and a black plateau hat. His drummer’s sleeveless shirt and floppy mullet and his bassist’s white boots and beret were part of the conspiracy to defy the zeitgeist.

The concert’s first two songs are semi-standard blues warm-ups. Song three is an astonishing cover of Hendrix’s “Voodoo Child.” The original is considered a rock classic, the kind of song aspiring guitarists spend hundreds of hours in their bedrooms trying to master. SRV’s version is superior to the original. Better sung, more energetic, more precise, a greater guitar vocabulary. Let me be clear: better than Hendrix.

Songs four (“Pride and Joy”) and eight (“Love Struck Baby”) are excellent SRV originals that will be familiar to anyone who listened to terrestrial rock radio during the 1980s, 1990s, or 2000s. The first song of the encore (“Lenny”) is as close as the show comes to a ballad. It’s lovely and deceptively sophisticated without ever giving up its blues roots. It’s the connective tissue between Dickey Betts’ major blues, Pearl Jam’s “Yellow Ledbetter,” and Mayer’s “Gravity.”

There is no doubt, however, that the concert’s high point is “Texas Flood.” I’m not sure if a more jaw-dropping blues guitar display has been captured on video. His dexterity. Those bends. Don’t take my word for it. There are YouTube compilations of people listening to the song for the first time. (This moment is my favorite.)

America created the blues. And the blues is the foundation of so much American music that followed: jazz, rock, folk, bluegrass, country, R&B, soul. But the blues itself never seems to get America’s center stage. The most important blues progenitors, like Robert Johnson, Charley Patton, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Willie Dixon, and T-Bone Walker, are still far from household names. Few of them had even modest commercial success domestically. Early rock ’n’ roll artists like Chuck Berry, Little Richard, and Elvis Presley were rooted in the blues, but that genre soon splintered into decidedly less-bluesy sub-genres: hard rock, arena rock, yacht rock, punk rock, art rock. In fact, the 1960s “Blues Revival” was led by non-Americans. Guitarists like Clapton, Jimmy Page, Jeff Beck, and Keith Richards discovered American blues in postwar England thanks largely to imported records, the 1958 U.K. tour of Muddy Waters, and the American Folk Blues Festivals starting in 1962. Amazingly, these young Brits ended up familiarizing American teens with their own musical patrimony.

So many of the incongruities of Live at the El Mocambo are commonplace for the blues; you might say, then, that SRV was just the latest artist to try to remind America of the genre. And the genius of Live at the El Mocambo wasn’t actually recognized until years later: The concert video was finally released in 1991, a year after SRV died in a helicopter crash at 35. Blues greats typically have to wait ages to be appreciated. When the Rolling Stones came to conquer America, they found their blues idol Muddy Waters painting the ceiling of a recording studio.

SRV’s early days didn’t exactly herald future greatness. As a child, his family bounced around the South, ultimately settling in Texas. His father was an abusive alcoholic. SRV dropped out of high school. But America’s greats are regularly unexpected. Who would’ve guessed our greatest poet would be a New England shut-in who refused to publish her catalog? Or that our greatest orator would be a former slave who taught himself to read? Or that our greatest leader would start as an unschooled kid nearly crushed by frontier poverty?

Maybe it’s America’s astonishing capacity to produce greatness that explains our unfamiliarity with so much of our own remarkable history. A fresh new marvel pops up constantly, demanding our attention. The silver lining is the ongoing opportunity to discover marvels from our past.

An Outside Read

Margaret C. Anderson was the editor of Chicago’s The Little Review and, perhaps most famously, was arrested for obscenity after serializing James Joyce’s Ulysses in 1920. I had no idea who Anderson was before I read a (well-written) review of a recent biography in The Atlantic, by Sophie Stewart. But while the review discusses the juicy details of Anderson’s life, it also questions what makes a good biography. “Every work of biography, no matter its scope, attempts the impossible: to impose order and meaning on a person’s existence,” Stewart writes. “And every attempt tends to emphasize the inherent chasm between a life and books about a life. The case of Margaret Anderson, who shook the literary landscape and then all but renounced it, brings this tension to the fore. She seems almost to dare her biographers to wrangle her, to make her life make sense. The editor in her might have liked to see them try.”

Stuff We Like

By James Sutton, TMD reporter

This isn’t a specific “thing” so much as an interesting project to watch: Tyler Cowen, the polymathic economist, and Patrick Collison, Stripe CEO and mainstay of the “progress studies” movement, have put out a (funded) call for a new artistic movement. “We’re more than a quarter way through the new century and we can now ask: what is the aesthetic of the twenty-first century?” Cowen and Collison write. “Which are the important secessionist movements of today? Which will be the most important great works? Today, futuristic aesthetics often mean retrofuturistic aesthetics. So, what should the future actually look like?” Importantly, they’re putting their money where their mouths are—at a website enticingly called NewAesthetics.art—and promising to fund artists who seek to answer those questions.

I share a lot of the conservative criticisms of modern art and architecture. But the best that those critics can seem to come up with in a response is a sort of neo-traditionalism that tends to be tacky and mawkish (see, for example, Trump’s redesign of the East Wing of the White House). So I’m excited to see what comes of this project, and I’m also interested to see if Cowen and Collison, both of whom move in libertarian and classical liberal circles, can avoid elevating social critique and commentary over “pure” artistic consideration, an issue that plagues the modern art world.

Work of the Week

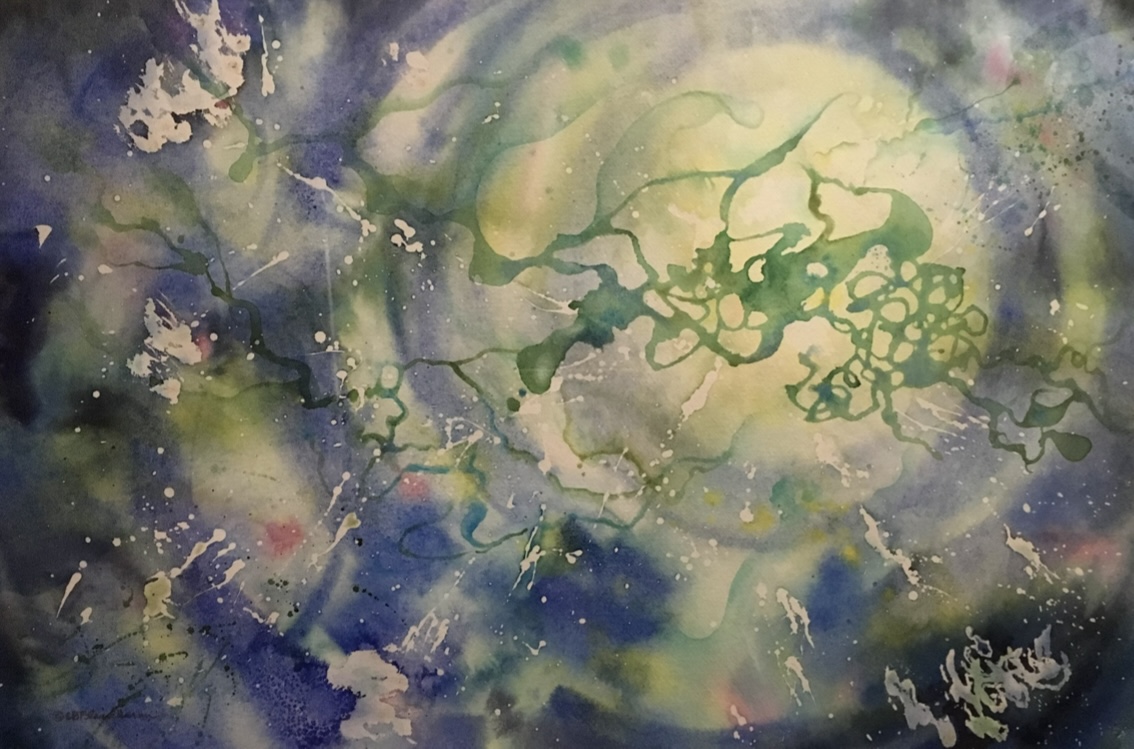

Work: Journeys Through Time, by Emily B. Fleischman

Why I’m a Dispatch member: I’ve been a member of The Dispatch since 2023 because I trust you. I trust you to know things that I should learn. I trust you to publish only well-researched news stories. And I trust you to report all sides of an issue or event.

Why I chose this work: My mother, Emily Fleischman, was a beautiful artist who practiced and taught art through her whole life, but it wasn’t until her daughters were adults that she fully gave herself to her creative spirit. This piece speaks to me of perspective, time, and creation, and its palette exerts an underlying peaceful energy that we would do well to appreciate in these fraught times. Journeys Through Time hangs in a private collection in Batavia, Illinois.

Interested in being featured in this section? Submit a work of art—by well-known or more obscure artists—here.

Interested in being featured in this section? Become a Dispatch member here.