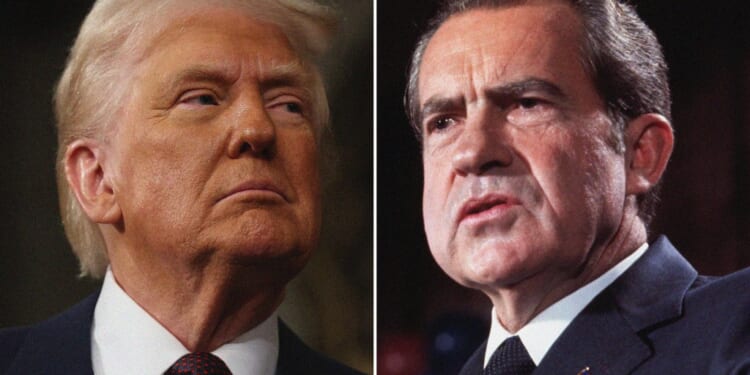

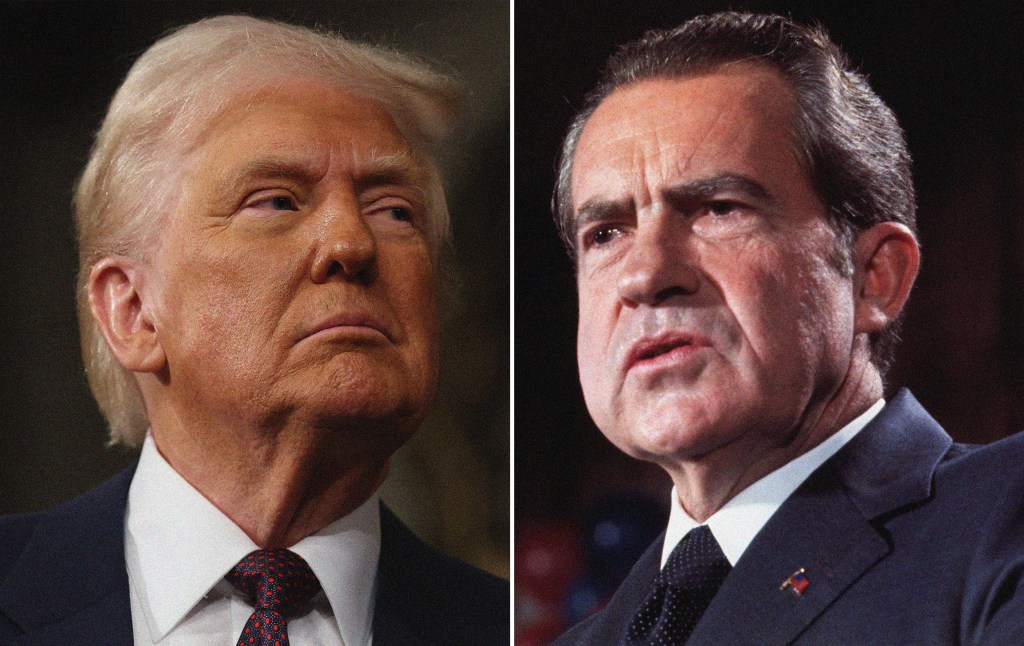

President Donald Trump has startled enemies and allies alike with his voracious appetite for overseas conquests in recent weeks, from Venezuela to Greenland. But once upon a time, the United States had a president who disavowed such American expansionism.

His name was Richard Nixon.

The occasion was the certification of the 26th Amendment 55 years ago, which extended voting to citizens aged 18 to 20. Nixon isn’t particularly known for his military restraint, but the comments he made on July 5, 1971, to a youth singing group heading overseas, stand in stark contrast to Trump’s philosophy.

“I have been thinking about what kind of a message you would be taking to Europe, what you would be saying,” Nixon told the youngsters, who ranged in age from 15 to 20. “You are going to be saying it, of course, in song, but you also will be saying it by your presence, by how you represent America.”

What they can be most proud of, he said, “is that you can tell anybody in Europe, in Asia, Latin America, anyplace in the world, that America in this century has never used its strength to break the peace, only to keep it. We have never used our strength to take away anybody’s freedom, only to defend freedom.” Nixon added that they could assure their hosts that America will use its strength to bring peace in the world.

“This is a very important thing,” he said, “because many other powers, when they reach the pinnacle where we are, the pinnacle of free world leadership, still had designs on conquests. The United States of America doesn’t want an acre of territory. We do not want to dominate anybody else. We want other people simply to have the freedom that we enjoy. That is what we believe in, and that is what you can say as you go abroad.”

Trump hasn’t made any secret of his own “designs on conquests,” threatening countries including Colombia, Iran, and Mexico, while reiterating his desire to take over Greenland. And that’s on top of his stated position that the United States is “going to run everything” in Venezuela.

It might be hard to take Nixon’s words about America’s peaceful intentions at face value. Less than two years earlier, he’d come up with the “Madman theory,” which sought to deter adversaries by suggesting he might just be crazy enough to drop a nuclear bomb. And the U.S. was in the midst of a divisive war in Vietnam that he had just broadened the previous year by invading Cambodia—which in 1973 led to the passage of the War Powers Act, the law that some in Congress are using in an attempt to rein in Trump today.

But Timothy Naftali, the founding director of the federal Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum—and no Nixon cheerleader—argued that what Nixon said about the U.S. not craving any territory was true during the Cold War.

“That’s what makes the current period so interesting, because what’s motivating the president, clearly by his own statements, are motives that American leaders have not had for well over 100 years,” he said in an interview.

Naftali said that while the invasion of Cambodia was a mistake, Nixon wasn’t trying to acquire the country.

“There was a strategic rationale,” he said. “The North Vietnamese had violated Cambodian neutrality at will. They’d never really recognized Cambodian sovereignty, and they were using it as part of the Ho Chi Minh Trail, and they had some bases there.”

Even in America’s notorious efforts at regime change during the Cold War, the U.S. was not motivated by land conquest, according to Naftali. While the American CIA helped orchestrate the coup that overthrew Iran’s elected prime minister in 1953, Naftali said, that was carried out to help Great Britain maintain its access to Iranian oil. American military intervention in Latin America, including in Guatemala and Cuba, was aimed at combating communism, not adding territory, Naftali said.

“I think that Nixon’s statement is interesting because it’s a reminder that presidents did not think they were seeking to dominate in the Cold War, whereas this president is making clear that that’s what we’re seeking,” he said. “He’s proud of the fact that he’s going to dominate the Venezuelan economy for as long as he wants to. And he wants to dominate the Arctic, and he wants to dominate North America, and he has made it clear that if he doesn’t like the leaders in South America, he’s going to overthrow them.”

Naftali noted that the Nixon administration declared 1973 “The Year of Europe” in an attempt to reinvigorate the partnership between the United States and its European allies (something that would be unimaginable from the Trump administration). “That was basically a way to say to Europe, ‘You probably think we forgot you, but no,’” he said.

“In terms of worldview, Nixon was an internationalist, and he was not a mercantilist,” he added.

There was another interesting comment by Nixon that afternoon in July 1971, one that contrasts with Trump’s America First philosophy.

“You can point out that as far as our wealth is concerned, that it isn’t something that is an end in itself,” Nixon told the teens and young adults. “We are not proud of it because we are rich. We are proud because what we have in the way of wealth enables us to do good things. … Whenever people in other lands have problems, we are able to help them.”

Wealth, he added, “it isn’t an end in itself; it should never be. If it does become an end in itself, then we are simply a rich country or a rich person living selfishly, thinking only of what is good for us.”