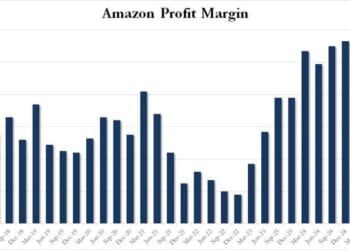

American democracy is in ill health. A growing share of voters (some 60 percent) are dissatisfied with the way our democracy is working and feel alienated from both major political parties. One factor is polarization: the growing emotional and policy distance and declining trust between supporters of the two parties. Another is the parties’ perceived failure to address the country’s economic and social problems. Related to this is a sense that both parties have become too captive to their most militant elements. A recent poll by Voto Latino found that majorities of voters felt that both parties have become too extreme: 56 percent said the Democratic Party is “too liberal or progressive,” while 60 percent said the Republican Party has become “too conservative or right wing.” In a September 2025 Pew poll, almost identical percentages of Americans identified each of the two parties as “too extreme in their positions,” and 56 percent agreed that the Republican Party under Trump does not “respect the country’s democratic institutions and traditions.”

Since 2006, Gallup has found that majorities or near majorities of Americans have consistently agreed that the two major parties do “such a poor job” of “representing the American people” that a third major party is needed. The most recent Gallup survey, in September of last year, found that 62 percent of Americans wanted a third major party, including not only most independents (74 percent) but 58 percent of Democrats and 43 percent of Republicans. In the abstract, most of these voters express an inclination to vote for such a party, but they concede what experts know: When such a choice is offered, voters peel away from it as the general election approaches because they perceive (correctly) that a third party has no chance of winning and they do not want to waste their vote on a “spoiler.”

Ranked-choice voting (RCV) for president in November (state by state) could ease this problem by enabling voters to cast a sincere vote for their first preference, knowing that if their candidate didn’t make it and no one won an initial majority, their vote would be transferred to their second preference. But RCV for the general election is probably a long way off.

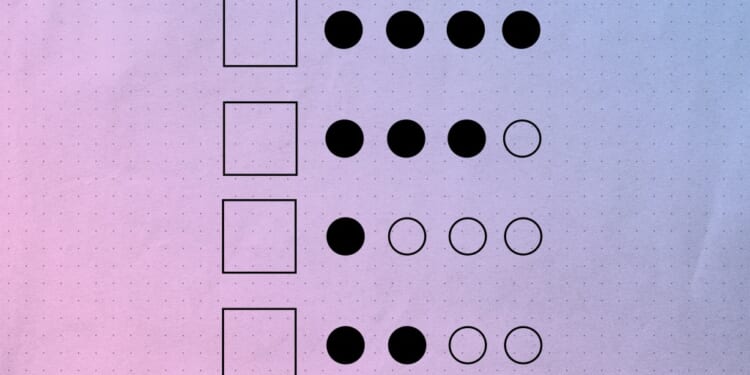

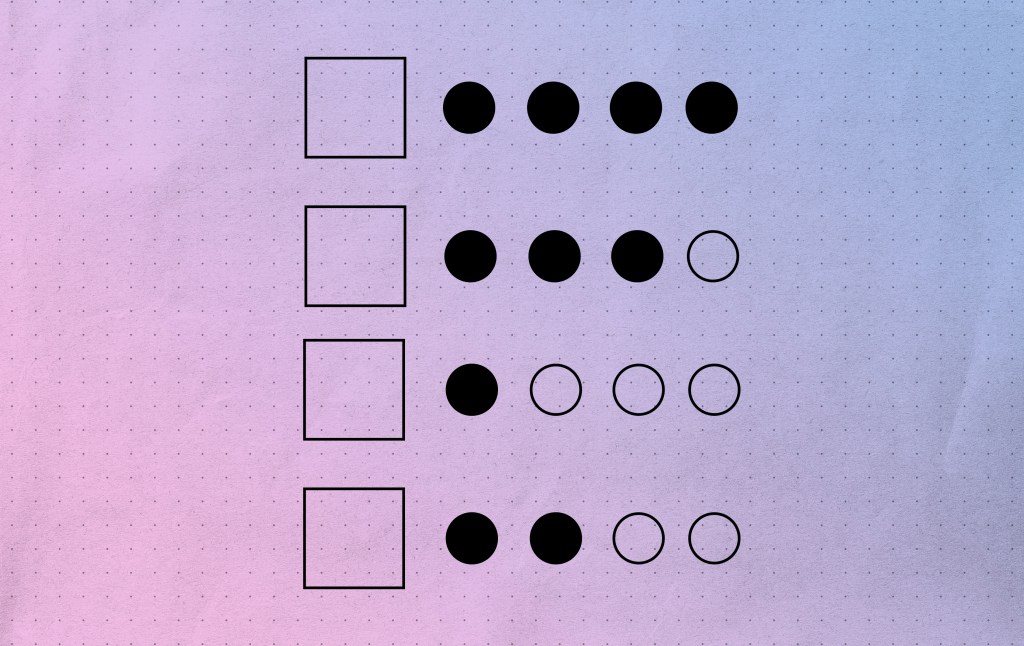

However, RCV could also make the nomination process of the two parties more interesting and inclusive, while producing more broadly appealing nominees. Under the system, voters do not vote for a single candidate but rank their top choices in order of preference. If no candidate wins a majority of first-preference votes, the one with the fewest such votes is eliminated and the second preferences of those voters are reallocated among the remaining candidates in an “instant run-off.” The process continues in additional rounds of instant run-off until a majority winner emerges.

RCV is typically used to select a single winner, but it could be adapted for our modern presidential state primaries, where the purpose is to award delegates rather than nominate a candidate in a single vote. All Democratic primaries (and some Republican ones) use a modified proportional rule to allocate delegates to the candidates. For the Democrats, any candidate who gets 15 percent or more of the vote gets a share of delegates proportional to their share of the vote. Currently, the votes for all the other candidates are “wasted” (not considered). RCV could make them count by reallocating those votes to the second or if necessary third preferences of the voters supporting the candidates who did not clear the threshold. What the parties should avoid is having a candidate declared a winner—and reap the lion’s share of delegates—with only a modest plurality of the vote.

“A more extended, inclusive, and deliberative process would not only be more democratic; it would also produce candidates who had honed the ability to forge compromises and craft broader appeals and coalitions.”

Larry Diamond

“Ranked-choice voting is a Rube Goldberg machine—a contraption of levers and pulleys designed to do a simple job in the most convoluted way imaginable, while promising that the complexity itself is a virtue.”

Matthew Gagnon

One problem with presidential primaries is that, in the absence of an incumbent, they often attract a plethora of candidates. In these fragmented primaries, candidates may “win” with as little as 25 or 30 percent of the vote. In New Hampshire, Pat Buchanan won the 1996 Republican primary with 27 percent, Donald Trump the 2016 Republican primary with 35 percent, and Bernie Sanders the 2020 Democratic primary with 26 percent.

One could argue that historically, the process has worked out well enough. Out of fragmented fields, candidates like Jimmy Carter, Walter Mondale, Bill Clinton, Barack Obama, Ronald Reagan, George W. Bush, John McCain, and Mitt Romney won their party’s nomination. Whether they won or lost in November, they enjoyed the broad support of their party and respected the rules of the democratic game. These outcomes did not destabilize American democracy, nor did they preclude significant turns in policy direction that American voters favored, for example, with Reagan in 1980 and Obama in 2008.

What is different about the current era is that American politics are much more polarized and the norms that sustain the health of our democracy—civility, mutual tolerance, and mutual restraint in the exercise of power—have badly eroded. In 2024, 40 percent of voters worried that the coming presidential election results might be violently or illegally overthrown. Eight in 10 voters now believe that democracy is threatened in the U.S. (and 7 in 10 strongly believe so). Majorities report feeling “exhausted” and “angry” about our politics, in large part because they are so “divisive,” “combative,” and “toxic.” Animosity toward members of the other party is at an all-time high. Now, Gallup finds, 45 percent of Americans (and majorities of voters under the age of 45) identify as independents, also an all-time high, with barely a quarter (27 percent each) identifying with the Republican or Democratic Party. Consistently since 2010, Gallup has found that around half of Americans prefer political leaders to compromise to get things done, while only a quarter want leaders “to stick to their beliefs even if little gets done.”

How might ranked-choice voting in presidential primaries address these currents of disaffection? First, it could make primary elections more interesting and inclusive by sustaining more of the candidacies deeper into the race. Second, sustaining more candidacies longer might also increase voter participation in primaries. Third, RCV would increase the prospect that the party would ultimately nominate a candidate with wider appeal in the electorate. This would not necessarily mean a candidate in the (potentially boring) center of the party, but rather one whose candidacy would represent a broader coalition of voters, assembled through the process of seeking and attracting second-preference votes. And fourth, RCV would lower the prospect of the party going off a cliff by nominating a candidate who would be viewed as extreme by the larger electorate (e.g., Barry Goldwater in 1964 or George McGovern in 1972), or who would govern in a polarizing and potentially undemocratic manner if elected.

As currently structured in most states, the presidential primaries have two other flaws. In contrast to the Democratic presidential primaries, which award delegates on a semiproportional basis, the Republican presidential primaries offer a variety of methods that include winner-take-all (either with any winning percentage, or if they cross a threshold of 50 percent of the vote). This system heightens the possibility that a more extreme candidate with an intensely loyal following could keep piling up delegates and marching to the nomination in a crowded field, sometimes with mere pluralities of the vote. This is not a healthy outcome for democracy, especially in an era of intense polarization and weakening normative restraints.

Also undermining the fairness of the process is the growing trend toward compression of the primary calendar, with big states scheduling their primaries early. Hence, as in the recent past (and perhaps even more so), the 2028 presidential primaries will be heavily front-loaded. Many states have already set early primary dates, including a March 7 “Super Tuesday” that will include primaries in California, Texas, Virginia, North Carolina, and Tennessee. By March 21, when Arizona, Florida, Illinois, and Ohio vote, the race may already be essentially over in one or both parties. Party leaders think this will position them to compete better in November, but it figures to short-circuit competition and privilege candidacies with intense followings or huge campaign treasuries that can buy up mass media in the early vote-rich primaries.

A better and fairer process would give voters more time to weigh the different candidates, and it would, through ranked-choice voting, make every vote count. In fact, the more compressed the electoral calendar, the more important it is for democracy that voters be able to rank their preferences.

What if a party wanted to ensure that every presidential primary vote counted, while also giving its primary contests a succession of weeks to winnow the field? First, it could use a purer form of proportionality to allocate delegates by requiring, as Richard Pildes and Frances Lee propose, that delegate allocation be entirely proportional to the popular vote statewide rather than allocating most of the delegates by congressional district. If the Democratic Party retained its rule (which Republicans would be wise to adopt) of awarding candidates a proportional share of the delegates only if they clear a 15 percent minimum threshold of the vote, RCV would then ensure that every vote counted. Voters who cast first-preference votes for candidates who did not pass the minimum threshold would have their votes transferred to their first (or, if necessary, second or even third) preferences in instant run-offs. The process would begin by transferring votes from the weakest candidates and continue until every candidate had either cleared the threshold or been eliminated. (The threshold might even be increased to 20 or 25 percent in later primaries.) With RCV, some trailing candidates with a resonant message or significant constituency might remain relevant in the race because the second preferences of their voters would be needed by the leading candidates. The leading candidates would then need to reach across divides to build more diverse and expansive coalitions of primary voters.

Such a primary electoral system would undermine the growing desire of the leaderships of both parties to anoint a presidential nominee as soon as possible. But a more extended, inclusive, and deliberative process would not only be more democratic; it would also produce candidates who had honed the ability to forge compromises and craft broader appeals and coalitions. That might help to pull our democracy back from its current downward spiral of polarization, extremism, and despair.