Second, the Greenland threat confirms what many policy experts (ahem) have been saying for years now: Trump’s “emergency” and “national security” justifications for U.S. tariffs are an empty, if not outright ridiculous, abuse of existing law. Regardless of Greenland’s strategic importance, there’s simply no plausible case for the situation in the Arctic to constitute a “national emergency,” or for Danish sovereignty over Greenland to constitute an “unusual and extraordinary threat” to national security, foreign policy, or the economy—both of which IEEPA requires. As George Mason University’s Ilya Somin notes, Denmark has controlled Greenland for centuries, and the idea that Russia or China might soon seize it is laughable. Regardless, NATO already defends it; existing agreements allow the U.S. to station troops there (which we have); and if there were a genuine, immediate threat in Greenland (there isn’t), our current alliances already provide the necessary defense mechanisms.

Trump officials’ unsurprising defenses of the president’s Greenland broadside acknowledge this reality—and the weakness of existing law. Over the weekend, for example, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent explained that, even though there’s no imminent risk of a Chinese or Russian invasion of Greenland, “emergency” tariffs on imports of NATO allies were lawful and appropriate because—and I kid you not—“[t]he national emergency is avoiding a national emergency.” Even leaving aside the president’s explicit, bizarre linkage of Greenland with his Nobel Prize snub, it’s just abundantly clear to everyone that the Greenland tariffs had nothing to do with protecting Americans from an actual, imminent threat and everything to do with coercing an ally into surrendering its own territory.

Third, the Greenland tariff threat demonstrates once again that Trump’s vague, unilateral, and non-binding trade deals are effectively meaningless—and that foreign government efforts to placate Trump can easily backfire. The EU justified its lopsided agreement with Trump last July on the grounds that it would at least lock in lower tariff rates for some European goods and calm transatlantic jitters. Just six months later, however, Trump’s Greenland threat has punctured the fantasy, confirming instead that U.S. agreements lacking congressional ratification are at the mercy of whoever occupies the Oval Office, and that efforts to appease Trump often simply encourage him to take even more.

As we’ve discussed, governments often retaliate against tariffs for strategic reasons, namely to show the instigator they’re willing to absorb some economic pain to punish bad behavior and to discourage escalation. To avoid an all-out trade war and other, non-economic harms (e.g., in Ukraine), European leaders and officials in several other governments have thus far preferred appeasement and engagement over direct retaliation. Their restraint clearly hasn’t worked and, far from stopping Trump, likely did the opposite.

With that bubble popped, the next question becomes whether the EU and others revert to a more traditional approach to retaliation. Strategic considerations aside, domestic politics might demand it, as European leaders increasingly face pressure from their own voters to stand up to Trump. As the Financial Times’ Alan Beattie reported Monday, the latest tariff broadside shocked Brussels into reconsidering its approach to Trump, and the EU officially paused ratification of the EU-U.S. trade deal on Wednesday. Now that Trump has backed down, the Europeans probably won’t move to apply targeted tariffs on around $110 billion in U.S. exports (previously approved but currently suspended), and the EU’s biggest gun—an “anti-coercion instrument” that could block U.S. services and investment or impose export controls—is surely off the table. That Europe was even contemplating it against the United States, however, is a depressing testament to how thoroughly Trump has poisoned the well. We should expect more tensions in the months ahead.

Finally, the Greenland chaos will give governments and supply chains even more motivation to move on without the United States. Mere days before Trump announced the tariffs, in fact, the EU and the Mercosur trade bloc (Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay) signed a free trade agreement that would eliminate most tariffs and create the world’s largest free trade zone. The EU is also close to signing a big trade deal with India, which is working on several of its own, non-U.S. deals. Around the same time, Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney announced a “new strategic partnership” with China, which included modest tariff reductions and was part of Canada’s broader efforts to diversify away from the United States. (Carney’s comments in Davos this week were even more explicit.)

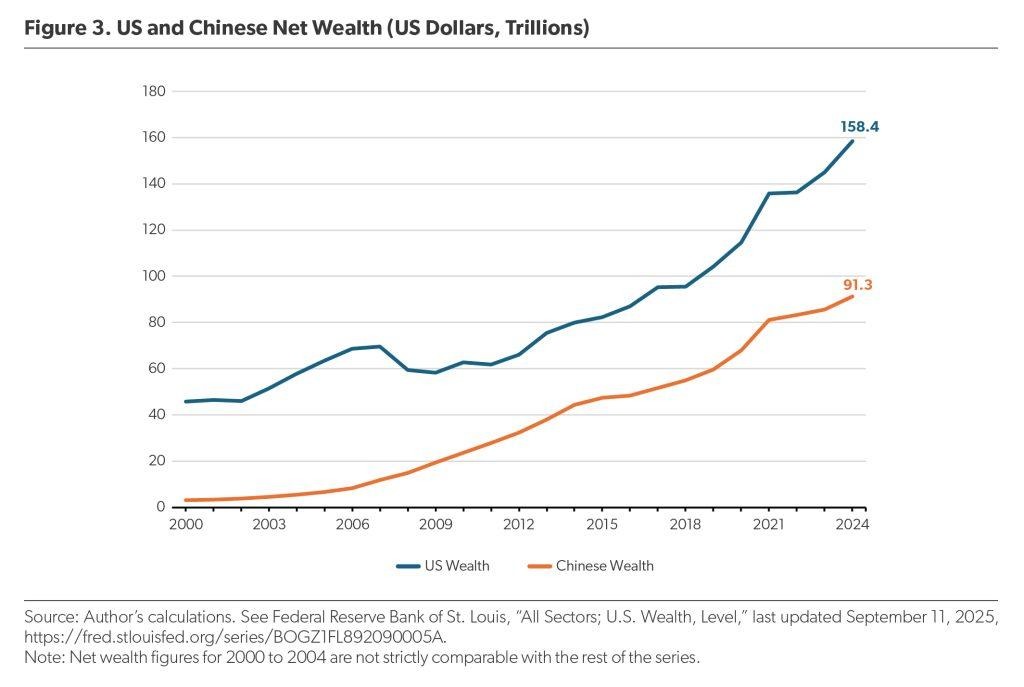

These moves aren’t silver bullets but also aren’t outliers. As Bloomberg’s Mihir Sharma documented earlier this month (and as we’ve discussed repeatedly), rising global trade flows outside the U.S. and the proliferation of non-U.S. trade agreements and supply chains show that few are following Trump into the isolationist abyss. Instead, people are finding ways to trade more with each other while limiting exposure to American costs and chaos (though they’re certainly not abandoning the giant U.S. market altogether). Trump’s Greenland tantrum will only accelerate the process, leaving us weaker and less relevant in the long term (and China stronger).

The Real Crisis: Emergency Powers

As annoying and depressing as the trade policy implications are here, the Greenland tariff threat reveals a bigger and more fundamental problem in the United States today: the total breakdown of limits on the president’s “emergency” powers.

The National Emergencies Act of 1976 was enacted to reform a system that let U.S. presidents declare multiple concurrent emergencies and keep them running indefinitely. The act establishes rules and procedures that were supposed to limit presidential emergency powers in various ways. As the Cato Institute’s Gene Healy testified before Congress in 2024, however, “the NEA had the unintended effect of normalizing emergency rule.” He notes, for example, that the 1976 Senate special committee charged with emergency powers reform “found it appalling that four national emergencies were then in effect.” Yet today we live under 50 active national emergencies, several of which date back decades and all of which unlock broad executive powers—under IEEPA mainly but also several other U.S. laws—that are typically reserved to Congress or delegated to the president in a much narrower fashion.

As the table above shows, emergency rule is an endemic, bipartisan affliction, with Trump responsible for just 16 of the 50 national emergencies now in force. Yet Trump is a clear abuser of the law, and his IEEPA tariffs—and now the Greenland threat—reveal three big problems with the current “emergency” system.

First, the vague and open-ended definition of “national emergency” has, along with extreme and undeserved court deference, allowed the president to declare almost anything an “emergency” and then unlock vast powers that can be completely unrelated to the emergency at hand. As GMU’s Somin explained for The Dispatch last July, this is particularly evident from Trump’s “reciprocal” tariffs, which were invoked under IEEPA to address “emergency” trade deficits that have been around for 30-plus years and that, most economists will tell you, are typically benign and can’t be “fixed” by tariffs at all. “If trade deficits are enough to trigger invocation of IEEPA,” he warned, “then the president will have virtually unlimited power to impose tariffs.” Just a few months later, Trump’s Greenland tariffs—threatened to somehow remedy a dubious “emergency” that hasn’t even happened yet—make Somin’s point clear. As Sen. Rand Paul stated over the weekend, “There’s no emergency with Greenland. That’s ridiculous… Now we’re declaring emergencies to prevent emergencies? That would lead to endless emergencies.”

Second, once they are declared, emergencies are almost impossible for Congress to end. As Healy explained, the Supreme Court’s 1983 decision in INS v. Chadha “effectively neutered the NEA’s mechanism for terminating emergency declarations” by nixing the legislative veto and requiring instead that termination “run the gauntlet of the ordinary legislative process.” In practice, this means that Congress must pass a joint resolution terminating a national emergency by a two-thirds supermajority to override an inevitable presidential veto. In today’s partisan environment, that’s a virtually insurmountable hurdle, as we saw with Trump’s 2019 veto of a resolution to terminate his border emergency declaration and more recently with House Republicans’ successful efforts last year to block even a vote on his “emergency” tariffs.

Unless the Supreme Court invalidates the IEEPA tariffs, they’ll likely be with us for years.

Third, partisanship also kneecaps the chances that NEA reform—or a broader curtailment of executive emergency powers—will ever happen. That’s because each party pushes for limits on presidential power when it doesn’t occupy the White House but loses interest when it does. In 2024, for example, several NEA reform bills advanced in Congress with significant Republican support, and for a brief moment it looked like something might actually get done in the fall. But then Trump won the election, and the effort died in December as GOP enthusiasm predictably faded. Today, Republicans who control Congress—and even once sponsored bills curtailing executive power—have suddenly discovered its virtues when talking about the Trump presidency and Trump’s tariffs.

To be clear, Democrats haven’t been much better. When Joe Biden was president, Democratic leaders lost interest in U.S. tariff reform and mostly shrugged at their guy’s various power grabs—including a student loan “emergency” that the left-leaning Brennan Center called “a dubious use of emergency authority … that could invite more troubling misuses in the future.” And, while many congressional Democrats are talking a big reform game at the moment, some of their presidential hopefuls are already plotting otherwise:

Democrats consider Trump’s actions an affront to democracy and the Constitution, but many of them don’t want to rule out exerting those same powers to undo Trump’s agenda. NOTUS spoke to members of Congress — some of whom are viewed as 2028 presidential contenders — along with strategists and scholars about how the next Democratic president could and should wield the power of the executive. Most expressed a willingness to use the new tools Trump has carved out, saying that if Republicans can do it, Democrats can, too.

I sincerely hope these Dems will get overruled by their reform-minded colleagues, but recent history doesn’t exactly inspire confidence.

Summing It All Up

If the Supreme Court invalidates Trump’s IEEPA tariffs, it’d be a win for all the reasons we’ve discussed. But the ruling would likely represent just one step forward on a longer path toward restoring real and sensible limits on executive power and some semblance of the checks and balances our constitution prescribes. Even if the president loses IEEPA tariff powers entirely (fingers crossed), for example, Healy’s testimony notes how the law leaves us many reasons for concern: “More troubling still, although IEEPA has so far been used mostly against foreign targets, nothing in the statute bars it from being turned directly against American citizens.” Other laws provide even more powers, and the NEA lies at the root of it all.

As much as I agree with Somin that the courts should be more active in reining in executive branch “emergency” declarations, judges don’t seem all that interested in taking this on. Indeed, it was telling that arguments in the Supreme Court tariff case barely touched on Trump’s “emergency” declarations and instead focused on the narrower issue of whether IEEPA allows for tariffs at all. It’s thus more likely that major reform will have to come from Congress, and if Trump’s bizarre Greenland push isn’t sufficient motivation, then I fear nothing will be.

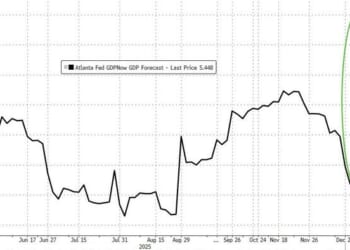

Chart(s) of the Week