Country music fans of a certain age will be familiar with “Bocephus,” Hank Williams Jr.’s nickname and swaggering bluesman alter ego. “My Name Is Bocephus” is a pretty good song, but the story of the name is tragic and practically Oedipal. Williams never really knew his famous father, who before sending himself to death via alcohol and morphine at the age of 29 had nicknamed his little boy “Bocephus” after a ventriloquist’s dummy that featured prominently in a Grand Ole Opry act. Hank Jr. began his career performing his father’s songs and songs in his father’s style—he was something very close to what we would today call a “tribute” act, his life dominated by the memory of a man he barely knew and could never live up to. (The family traditions must have aged him: He released “All My Rowdy Friends Have Settled Down,” lamenting middle-aged decline, at 32.) And even after Hank Jr. went off to explore new musical directions, he continued to be “Bocephus,” the little wooden man mouthing someone else’s words and dominated by forces beyond his control.

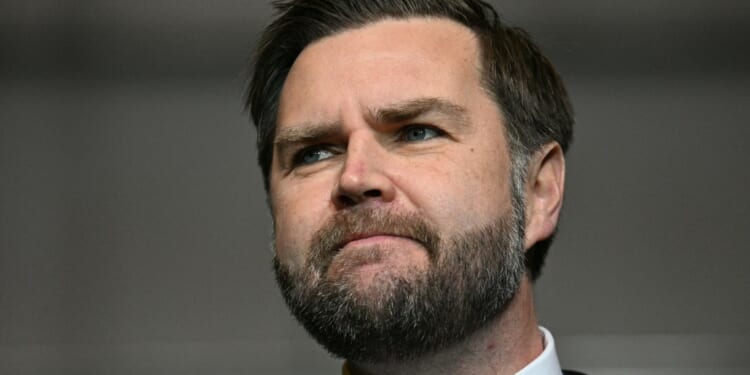

The outline of the story is familiar enough, and one might wonder whether J.D. Vance, another obviously troubled son of an absent father, is entirely comfortable with Donald Trump’s hand up his backside working his mouth. It is fortunate for Vance that Trump has such famously diminutive fists.

Trump, for all his condescending to the heartland, is not a character from country music. He is a character from Englishman George Crabbe’s poetry—specifically, he is Peter Grimes:

No success could please his cruel soul,

He wish’d for one to trouble and control;

He wanted some obedient boy to stand

And bear the blow of his outrageous hand;

And hoped to find in some propitious hour

A feeling creature subject to his power.

Who could doubt that the author of Hillbilly Elegy is a feeling creature as well as an obedient boy? Depraved and debased, of course, and entirely dominated by the lowest kind of ambition, but certainly a feeling creature and an obedient boy. Vance is someone who fills me with a kind of personal dread and terror because I see something too near to myself in him. Men who start off toward the bottom and want to work their way up have only a few different ways to go about it, and Vance has chosen the familiar path of seeking patronage, which is not necessarily dishonorable. When you are someone like young J.D. Vance, there is always someone standing between you and the thing you want, and the power to give you the thing you want or deny it to you is in that person’s hands. Some men—and Vance is the textbook example—get very, very good at telling people who can give them what they want whatever it is they want to hear: Hillbilly Elegy is, among other things, Vance’s cover letter to a certain class of Economist-reading policy intellectuals and pundits, a big heart-shaped Valentine’s candy box full of moral flattery that they (er, we) were gratified to receive.

When Vance wanted to enter politics, the man standing between him and what he wanted was Donald Trump, the dimwitted bigot and retired game show host whom Vance had once described—in perhaps his last unequivocally truthful statement of any relevance in public life—as “unfit for our nation’s highest office.” Then the would-be Ohio senator, whose patronage-seeking by that point was the defining feature of his character, adroitly turned on his heel and told Trump what Trump wanted to hear, i.e., that he would serve as Trump’s personal political catamite in exchange for an endorsement. Trump’s endorsement was enough to carry Vance to the Senate, but the election highlighted the limits of Vance’s personal appeal: He won his race by 6 points in a year when Mike DeWine, the Ohio governor running for reelection on the same ballot, won by 25 points—and Republican candidates for treasurer and attorney general won by 17 points and 21 points, respectively. One in 10 Ohio voters chose DeWine and then crossed the party line to withhold their votes from Vance.

Trump’s contempt for Vance is visceral: Vance’s short career at a Silicon Valley investment firm is not the sort of business story that impresses Trump, who toward the end of his career in real estate was such a proven financial deadbeat that he could not secure an ordinary bank loan, and Vance was foisted on the 2024 Trump campaign by three of the few people for whom Trump has an even more evident contempt than he holds for Vance: his idiot sons and Tucker Carlson. Trump is said to have preferred Doug Burgum, the billionaire software entrepreneur turned real-estate developer, whose business career and clean-cut businessman’s personal presentation appealed more to Trump’s sensibility than did the prospect of spending his second term in office with a bearded and once pudgy former National Review contributor. (One sympathizes.) But Uday and Qusay and the Swanson boy prevailed on him, convincing Trump that Vance was the key to the podcast-bro vote, and possibly a direct line to the pockets of billionaires such as Peter Thiel, Vance’s principal business patron, and Elon Musk.

Trump, a veteran of professional wrestling as well as reality television, is an instinctive maker of lowbrow storylines, and, just like any given season of Real Housewives, the Trump administration has only one plot: rivalry that escalates from cattiness to an open brawl. Vance has been set against Marco Rubio, secretary of state and … pretty much everything else, to seek the prize of Trump’s support for the Republican nomination in 2028. (This assumes Trump both survives his presidency and then leaves office on schedule rather than offering up another plot twist.) Vance, who is not stupid, must know that he is getting the short end of it: Every time someone suggests that Vance is a man on the rise in Trump’s presence, the president goes out of his way to build up Rubio, who has been given about seven-tenths of the important portfolios in the administration while Vance is left to act as a social media troll running defense for the likes of neo-Nazi turdling Nick Fuentes—which is to say, Rubio gets the glamorous jobs while Vance gets to be a toxicity sponge soaking up all the disreputability that the administration brings upon itself while working to keep Kanye West, Candace Owens, Andrew Tate, and the kid from that last scene in Cabaret on the team.

William Makepeace Thackeray knew what life was like in Vanity Fair, which was a novel before it was a celebrity magazine and a Christian metaphor before it was a novel: “Everybody is striving for what is not worth the having!” J.D. Vance is a striver, but he does not understand the nature of the ventriloquist’s act—the dummy is an instrument, not the star of the show. The star stays the star, and the instrument—in this case, an instrument of chaos, stupidity, and immorality—well, dummies stay dummies, don’t they?