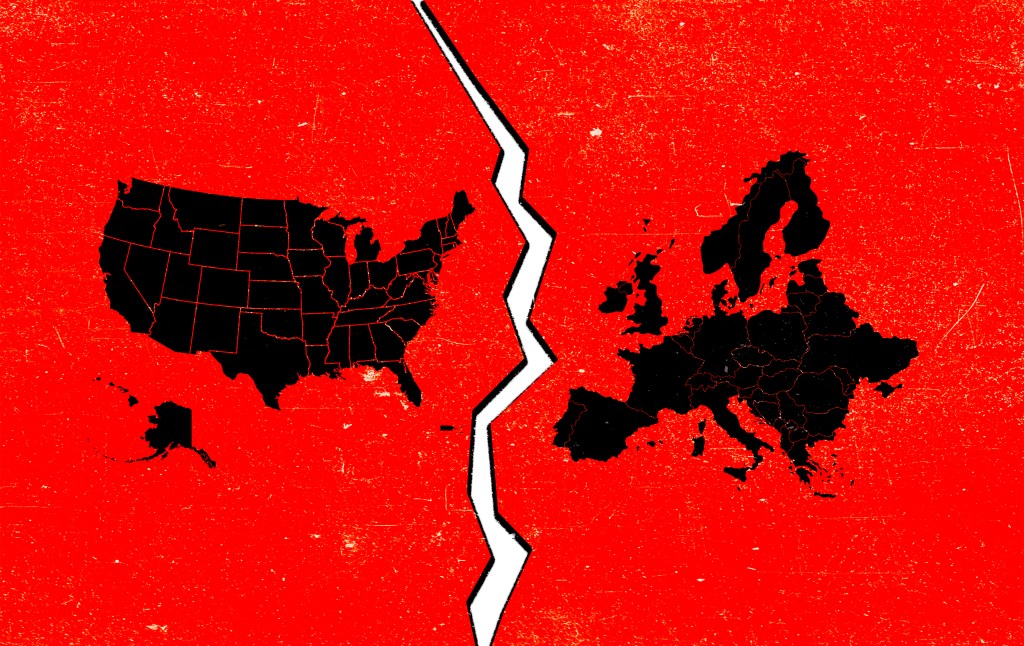

For all but the chronically disengaged, it is difficult to reflect on the past year of Donald Trump’s presidency without concluding that the world order is undergoing a brutal demolition. For those of us appalled by it, it is tempting to fall back on the notion that it reflects the pathologies of one personality, and that the damage might be halted by distracting him or, time and Trump permitting, the results of an election or two.

But this would be to ignore the fact that at least a sizeable minority of the American electorate either supports the president’s actions or has no beef with them—including his deposal of Venezuela’s Nicolás Maduro; his threats against Cuba, Colombia, Panama, Mexico, Canada, and Greenland; his scorning of NATO; his sellout of Ukraine; and his dismissal of international law more broadly. A Wall Street Journal poll finds that a rock-solid 92 percent of Trump voters approve of his performance, and 70 percent “strongly approve.” If they turn against him, it will be over rising electric bills, and not his contempt for liberal order.

That order was the product of elite thinking in Washington and New York some 80 years ago, when the United States was at the apex of its military, economic, and diplomatic dominance. During and immediately following World War II, the Roosevelt and Truman administrations spearheaded the creation of an enormous latticework of international rules and norms relating to everything from trade and currency to labor and human rights to diplomacy and war. This universalist thinking was reflected in the architecture of the United Nations (1945), the International Monetary Fund (1945), the World Bank (1945), and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (1947), although even the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (1949) and the European Coal and Steel Community (1951)—offshoots of the early-Cold War Marshall Plan (1948)—aimed at furthering universalism by placing the defense and expansion of democracy at its heart.

As extensive as this legal latticework was, it could neither cover all exigencies nor resolve contradictions. In practice, it relied on the United States to initiate action as a kind of Aristotelian uncaused cause, godlike from outside the system, while generally forgoing the type of nakedly self-interested behavior that would openly deny the order’s authority.

By historical standards, the project was astoundingly successful—not in that all nations conformed, since the United States itself at times strayed willfully and radically, but in that virtually all nations felt compelled to align themselves with it, to argue for alternative understandings of it, or to justify their deviations from it. As Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney said Tuesday at Davos, “Countries like Canada prospered under what we called the rules-based international order. We joined its institutions, we praised its principles, we benefited from its predictability. And because of that, we could pursue values-based foreign policies under its protection.”

Still, he continued, “We knew the story of the international rules-based order was partially false, that the strongest would exempt themselves when convenient, that trade rules were enforced asymmetrically, and we knew that international law applied with varied rigor, depending on the identity of the accused or the victim.” On balance, though, “this fiction was useful, and American hegemony in particular helped provide public goods, open sea lanes, a stable financial system, collective security and support for frameworks for resolving disputes.”

And so, Carney concluded, “We participated in the rituals, and we largely avoided calling out the gaps between rhetoric and reality.” But “this bargain no longer works.”

The rules-based order rested on a fundamental paradox. Liberal universalism held that decisions had to be taken through the liberal doctrines of deliberation, compromise, and proceduralism—none of which could ever ensure timely and effective action. Such an order cannot acknowledge the limits of liberalism without undermining its own moral premise—that no decider can stand beyond the system, imposing its will as a supposed means of maintaining it.

This paradox was unproblematic so long as the U.S. behaved so as not to make it manifest. But the slow-motion death of the World Trade Organization shows how it can prove fatal.

Launched in 1995, the WTO operates a Dispute Settlement Mechanism and Appellate Body that arbitrates trade disputes. For many years, it functioned well, peacefully settling conflicts over rules and practices. The DSM can reasonably lay claim to being the crown jewel of post-Cold War supranationalism.

U.S. frustration with the system, however, began growing rapidly after China’s WTO accession in 2001. Key features of China’s state-capitalist system—such as subsidized capital, coerced technology transfer, and systematic overcapacity generated by industrial policy—were beyond the organization’s ability to discipline. Yet it also denied Washington a free hand to counter China’s abuses with protective trade barriers.

In 2011, the Obama administration, objecting to the Appellate Body’s scrutiny of American antidumping and countervailing duty determinations, refused to allow the reappointment of an American judge, Jennifer Hillman. Since 2017, early in President Trump’s first term, the U.S. has blocked all appointments to the body, rendering it inquorate and unable to function. From that time, the U.S. has also repeatedly justified new trade barriers on the grounds of “national security”—which it insists are not subject to review. Consequently, many other countries have followed suit, leading to a global proliferation of new trade barriers, all justified by “national security” concerns.

The moral of the tale is that the WTO’s liberal rules and proceduralism worked well only so long as nations followed the lead of the United States and restrained their use of export subsidies, import barriers, and measures contradicting accepted principles of free and fair trade. But once trust and good faith were undermined by the deadly dialectic of Chinese abuses and U.S. reaction, argument and deliberation within the body became performative, no longer aimed at actual resolution. Absolutist serial moral pronouncements and specious “national security” invocations replaced reasoned dialogue. Enforcement became impracticable. And so the WTO became a zombie body, shorn of its animating purpose. This same process is now playing out within NATO, where long-standing U.S. frustrations over its disproportionate funding burden have, with the return of Donald Trump to the White House, boiled over into an open assault on its raison d’être as defender of a European liberal order.

At the broadest level, the breakneck rise of China as an illiberal superpower has fatally undermined the role of the United States as the hegemon ex machina, holding together a liberal order from beyond it, and making plain the paradox that had always underlain it. That order could not survive the proliferation of rules without enforcement, legalism without legitimacy, and procedural fixation amid conflict over fundamental values. This last problem—the absence of underlying common values within a liberal order—has been a central source of concern among political philosophers and juridical scholars from Leo Strauss on the reasoned right to Carl Schmitt on its far anti-liberal extreme.

The logical limitations of liberal order are perhaps nowhere better captured than in the writings of psychiatrist Iain McGilchrist—although he has, to my knowledge, never actually written on the question. McGilchrist contrasts rationality, a left-hemisphere brain preference, with reason, a right-hemisphere preference. Rationality is rules-based and detached from lived reality. Reason is context-sensitive, grounded in experience. The tension between the desires for rationality and reason is mirrored in the functioning of the liberal order.

The United States has long evinced a “split brain” outlook on the system—believing, on the one hemisphere, that the rules-based liberal order was rational, all-encompassing, and self-regulating, and, on the other, that Washington required discretionary reasoning in the conduct of its own affairs. This can be interpreted, as Schmitt surely would have interpreted it, as hegemonic hypocrisy. But it also reflects a certain animating naïveté in the Washington of 1945—a belief that the United States, the sovereign incarnation of liberal principles, could never be unduly constrained by the universal application of those principles.

Nowhere is the flaw in this belief clearer than in the evolving U.S. approach to the International Court of Justice—created, like much else in the universalist firmament, in 1945. The U.S. has long supported the ICJ as the principal judicial organ of the United Nations. Yet it has, over time, placed increasingly strict limits on the ICJ’s authority over U.S. action, withdrawing entirely its acceptance of compulsory jurisdiction under Article 36(2) of the ICJ Statute in 1986, when Nicaragua charged it with violating international law on the use of force. It turns out that when the rationality of the rules-based system the U.S. created clashed with the reason it applied in determining its vital interests, its reason won out. Still, it has remained vocal in supporting ICJ decisions against adversaries—such as Russia, over its invasion of Ukraine. Herein lies the contradiction highlighted by Carney.

It is hard to imagine the willful destruction of the liberal order being undertaken by any plausible alternative president—or at least not with the brutality of Donald Trump. Still, the signs of its crumbling have been evident for years. It tracked the relative decline of the United States, economically and militarily, vis-à-vis China, which eroded American willingness to sacrifice short-term advantage to long-term stability.

Even as Trump pulls back from his threat to invade Greenland, the broader trajectory is unmistakable. We are drifting—not by accident, but by structural necessity—toward a world that looks far less like the liberal universalism of 1945 and far more like the balance-of-power order of the late 19th century: spheres of influence, managed rivalry, and transactional diplomacy. The United States will dominate the Western Hemisphere; China will dominate the Asia-Pacific; Russia will contest Europe’s eastern frontier. International law will persist, but as rhetoric rather than restraint.

There are no obvious winners in this world. Economic growth will fall as trade walls rise. Border-blind threats—to health, to the environment, to financial stability—will rise as cooperation falls. Wars will be quicker to start and harder to end. This world was always latent in liberal universalism itself. Trump did not invent its contradictions; he merely stripped them of their euphemisms.