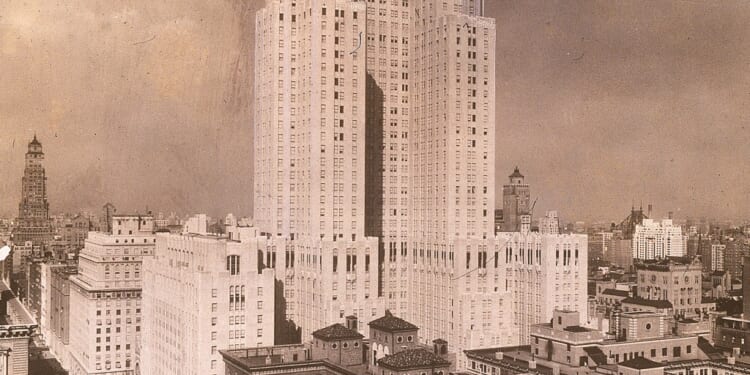

Three storied hotels have undergone extensive renovations in the last decade: the St. Regis (opened in 1904) and the second Waldorf-Astoria (1931) in New York, and the Ritz (1898) in Paris. And despite some muddled rhetoric about places that are both “timeless” and “new,” all three manage to selectively tap the past.

At the Waldorf, in the interest of enhanced service, the number of guest rooms has been halved and made at least twice as large. Suites are given the names of bygone guests, Cole Porter’s piano has a proud place in the lobby, and even the structure itself has been changed to create effects that the builders of the original 1931 edifice had planned to execute but did not have the skills to do. The Peacock Alley, where the fashionable strolled and strutted, happy to be seen, has been brought back to its old elegance.

The St. Regis pays homage to the post-Gilded Age of Caroline Astor and her son John Jacob Astor IV, who opened the hotel in 1904 as a place where his family and friends, the “Society” of Four Hundred New Yorkers led by the Mrs. Astor (aka “Queen Caroline”), would feel at home. That home is remembered on the ground floor with chairs embellished with embroidery and fringe details of the kind that Caroline Astor displayed on her gowns, an accent on plush purples and emerald greens, and a “drawing room” where an original collection of books from the old Scribner’s that Astor ordered for the hotel can now be seen for the first time. Other echoes of the past show up in the butler service and a revived Astor breakfast room.

At the Ritz Hotel in Paris, an extensive four-year renovation was completed in 2016. The hotel’s 18th-century decor was maintained, though refurbished, and the hotel’s heating and cooling systems were replaced. The number of rooms was reduced from 159 to 142, of which 71 are suites. Many of the themed suites pay homage to illustrious guests from the past: Marcel Proust, Maria Callas, and Coco Chanel, who lived in the hotel from 1937 to 1971.

The architect and designer behind the renovation of the Paris Ritz summed it up well: “My vision,” said Thierry W. Despont, “was to keep the Ritz exactly as it was, but better.”

It is not, of course, unusual to market the past. It is, however, of considerable interest which past is chosen.

These hotels take us back to an opulent time. They first opened when the wide gap between Old World and New had narrowed: Just when class distinctions in European hotels started to break down, they took on more importance in American ones. When César Ritz was luring private royals into his public hotel, America’s self-appointed royals, who lived in opulent mansions that rivaled any French chateau, often stayed out of the public eye. If they did patronize hotels, they did it discreetly.

The first Waldorf-Astoria (1897) tried to have it both ways. “I’d rather see Mrs. Stuyvesant Fish enjoying a cup of tea in an all but empty Palm Room than a dozen lesser-known guests there feasting,” said manager George Boldt. He saw that the presence of a Mrs. Fish—indeed of a ballroom full of them—was what would count most. To help make the hotel a citadel of Society, he even turned the hotel’s opening night into a celebration of its pet charity. But at the same time, Boldt said that he sold “exclusiveness to the masses.” What this meant in practice was that “Society” (which didn’t mean much more than rich people) patronized the Waldorf and the less well-to-do showed up in Peacock Alley to gape and bask in their presence.

There are some ironies in a celebration of the Gilded Age that are hard to ignore. To go to Colonial Williamsburg and visit our colonial (if prettified) past is instructive. But how should we understand the late 19th-century period when America fully entered the world stage? Politicians and robber barons worked hand in hand, and along with great fortunes came skyrocketing inequality—conditions not unlike our own time. If, as some argue, we now have a second Gilded Age, then looking more closely at the original age’s fascination with wealth—and its formation of a new American elite—is instructive.

A glance at our American hotel history should remind those who have forgotten what a new world struggled to create. To follow all the twists and turns in our hotel history is a crash course in American manners and mores, a lens on an insecure, often defensive class system. At the start, a new republic had to wrestle with how the people of a new land would behave. How should George Washington be addressed? Should one bow to the president? Should a domestic be seated separately from the family?

Most historians identify the Tremont House (1829) in Boston as the prototype for the modern hotel. Four stories high, it offered its guests a level of comfort and service that far exceeded our earlier taverns and inns. There was a splendid rotunda, which served as a true reception area (no barroom entrance here), 150 bedrooms equipped with a lock and key (no shared rooms), a library stocked with newspapers and magazines, parlors for ladies and gentlemen, a large dining room, and eight “water closets” on the ground floor. Soon after, the Astor House (1836) on lower Broadway in New York outshone the Tremont House, and the competitive race began. Built by John Jacob Astor, it was six stories high, had 300 elegantly furnished rooms, a ground floor of shops, an immense dining room, and this time, water closets above the first floor (and 17 “bathing rooms” plus two showers in the basement).

English visitors soon admired the plumbing and the other technological marvels which the American hotel pioneered. They had a somewhat mixed response about the increase in splendor and opulence. At New York’s St. Nicholas Hotel (1853), there was so much gold that an English comedian joked that he was reluctant to put his shoes outside his door for fear that someone would gild them. But most of all, they disparaged our manners (those spittoons!) and our gregarious sociability. Visitors remarked at how filled the hotel’s public spaces were and how very few Americans wanted to retire to their private rooms. It was, moreover, difficult to obtain room service (but available, in fact, in both the Tremont and Astor hotels). Even more peculiar, Americans lived in these hotels full-time. As Anthony Trollope wrote in his book on North America in the early 1860s, couples often found it more convenient and enjoyable to live in a hotel than to set up a house. “The mode of life,” he wrote, “is to their taste.” (Trollope did concede that there were other practical reasons for many “permanents”: Housing was hard to find and a mobile “on the go” people might want to move on in a year or two.)

Equally incomprehensible to the English was the way that some hotel managers saw their roles. Charles A. Stetson, the second manager of the Astor House, said that “a hotel keeper is a gentleman who stands on a level with his guests.” There is a sleight of hand here, an effort to both pull rank and deny its existence: Stetson elevates himself to the rank of gentleman and pulls everyone up with him. As the proud product of an equalitarian age, he knew that it was politically incorrect to place oneself above or below anyone else. A “sovereign” people was the cant of the age, and there was no talk of “servants” and “masters.”

This democratic posture would have been unthinkable in England, where the distance between guests and the people who served them was scrupulously maintained. Ex-servants James Brown, a valet, and James Claridge, a butler, managed to run hotels for the well-born because years of service had taught them what was required and they knew their “place.” Guests did not promiscuously mingle: At Brown’s Hotel (1832) it took decades before a public restaurant room (as opposed to meal time in one’s room) was available. In France, as well, a distinction between guest and host remained. Even César Ritz, who was known as the “host of kings, king of hosts” knew his place, since he had spent many humbling years observing and catering to Europe’s aristocrats.

In America, then and now, it is more difficult to classify people or to define anyone’s place. While the first six presidents could be described as “gentlemen,” when Andrew Jackson entered the White House in 1829 it looked like his supporters (who turned the presidential reception into a free-for-all) would not tolerate social hierarchy of any kind. Yet it seems we are still ambivalent about traditional notions of deference and position.

The well-to-do who assembled in the dining room of the Astor House were perfectly aware of these democratic sentiments. Whatever men might privately think, it was not the time to flaunt one’s advantages or claim special privileges. And almost any feature of hotel life could be suspect, such as whether soft sofas might undermine republican mores and whether it was monarchial, hence un-American, to dine in private?

If (as was so obviously the case) those who could afford the Astor House were an elite of sorts, there would have to be a new social code to govern their conduct. There were in fact few guidelines and there were literally scores of books—Frances Milton Trollope’s Domestic Manners of the Americans (1832), her son Anthony Trollope’s North America (1862), Frederick Marryat’s Diary in America (1839), and Charles Dickens’ American Notes (1842) to name a few—that disparaged republican manners, from the yellow spittle that stained our floors to the deplorable way some Americans behaved at table. These criticisms could not be wholly ignored: The visitors who looked at our hotels used them as a benchmark for our civilization, a shorthand proxy of who we were as a people. Indeed, the hotel was a laboratory, the place where the new species could be tested and examined.

In the end, it was the hotel itself that worked out an acceptable social code. It decided who was a “gentleman”—a key word in hotel life for a very long time and still used, although by now it has an almost quaint sound. At the Fifth Avenue Hotel (1859), it was said a man “had to be a gentleman and to be in first rate condition” to get into the Fifth Avenue bar. In the Midwest, at an inn on the frontier, when a lady objected to the used sheets on her bed, she was told: “There ha’nt ben nobody slept in these beds but some very nice gentlemen.”

Ladies and gentlemen! The touchy issue pushed buttons as late as 1919 in a small Texas town, when Conrad Hilton changed the signage on the toilets at one of his hotels to “men” and “women,” from “gentlemen” and “ladies”—thereby causing an uproar from guests. To complicate matters, hotel staff also weighed in. Some staff were remarkably democratic. As Oscar, the Swiss-born maître d’hôtel at the first Waldorf said, American boys did not make good waiters because “they considered themselves as good as the guests.” Other staff were not democrats at all, as cataloged by Frederick Van Wyck’s 1932 book Recollections of an Old New Yorker. When he was offered a $20 gold piece from the Prince of Wales, who had been a guest at the Fifth Avenue Hotel, an attendant politely refused. “I am,” he said, “the Head Porter of the Fifth Avenue Hotel.” Apparently, if he accepted a tip his own prestige would be compromised.

In effect, there were at least two quite different standards, a social elite that was largely based on wealth, and one that had been formed over time, based upon family pedigree, a respect for tradition, an educated taste, and a certain discretion. For the first, the hotel often functioned as a stage set, and guests were eager to see and be seen. For the second, if the hotel was patronized at all, it would be as private, understated, and reclusive as possible.

For the most part, the first standard prevailed. Still, the old guard had some lasting influence: John Jacob Astor, a butcher’s son, was said to eat his peas with a knife, but his heirs soon learned how to behave. Money sowed the seeds of a new American gentleman. Good manners and the passage of time did the rest.

Looking at the past reminds us that we remain on a seesaw when it comes to class in America. By the late 19th century, a “Society” based on money—and not very old money at that—was enough to transform republican life into a class system. But in the modern era we have gone far beyond the either/or class system described earlier: Neither mere wealth nor family pedigree has the prestige both once enjoyed. It is unclear whether hotel choice is now tied to concern about status. The global world we now inhabit somehow blurs all categories.

We can, in effect, be in Paris or New York (or indeed anywhere on earth, from the Taj Mahal Palace in Mumbai, The Strand in Rangoon, or Raffles in Singapore) and we do not find much difference. We can get a whiff of past glories, and the locations may prove different. But true cultural difference, a way to distinguish one place from another, a true local accent, all of these are often absent. As for any idea of “Society,” it seems almost as passé as any sort of dress code or indeed, manners. But that is another story.