Authored by Jeffrey Tucker via The Epoch Times,

The postwar trading order is taking on an entirely new shape.

We can put brackets around the old one, like a tombstone: 1944–2025.

Having known some of the economists and statesmen who put together the old order, I’m in a position to explain what they had in mind and also what went wrong with it. What will replace it is still very much in flux but the outlines are being drawn daily.

Let’s go back in time to Oct. 29, 1929 when the stock market crashed. There was panic in the air and great confusion about what to do and what not to do. However, absent any serious action by government, the financial markets began to recover over six months, even as downward price pressure on commodities began to show.

Congress responded with a very large increase in tariffs. The reason was partially a holdover from what had happened two decades earlier. The income tax had replaced reliance on tariff revenue, and many members of Congress had their doubts about this change. Indeed, resentment against the income tax was growing. Reverting to tariffs and away from a drive to free trade seemed like a possibility.

Many economists at the time warned about this tariff act. The concern was that this would shatter relationships with foreign markets when they were most fragile. The entire financial and industrial world at the time, including many small farmers, were concerned that this action was ill-advised. There was no love for the income tax but bringing back the tariff was deeply unpopular within professional circles.

The day that President Herbert Hoover signed the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act was June 17, 1930. That very day, the stock market stopped its trajectory toward recovery and reversed. Over the course of the several weeks surrounding this act, financial markets fell fully 20 percent. Lacking another explanation, all eyes turned toward the tariff bill as the cause. A few years later, those tariffs started to fall.

This prompted two huge commitments on the part of the upper echelon of opinion makers, economists, and statesmen. They blamed the decline on the tariff, deploying the crude analytical tool “After this, therefore, because of this.” Therefore, first, they committed themselves to a long-term plan to restore the downward trajectory of tariffs. Second, they decided to remove discretion over tariffs from Congress and put it entirely in the hands of the executive.

That’s where matters stood as the Depression went on and on and economic conditions continued to decay. The New Deal did not work to end the economic crisis, despite what they say. Even as the nation marched forward to yet another war, the economic problems persisted.

After the war, the forces for freer trade and against tariffs got their chance. The Bretton Woods agreement of 1944 was all-encompassing: finance, monetary rules, and trade. The trade piece of this was to be the International Trade Organization but it was never ratified. Instead, we got the much milder General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade. As a separate agreement, a new version of the gold standard was revived. In the new iterations, nations would stop promising domestic convertibility of money. Rather, accounts between nations would be settled by physical shipments of gold.

This was called the gold-exchange standard. It established dollar supremacy for the main parts of the world economy. There was always a problem with the plan, one known from the start. Nations using the same monetary standard also need to coordinate fiscal and monetary policies, a scheme that was impossible to deploy among all sovereign nations. A second problem is that without such settlements, wages and business costs across nations could remain permanently divergent, giving exporting nations an advantage over importing ones. With the dollar as the world standard, the United States stood to lose all manufacturing advantages should the agreement ever break down.

By the late 1960s, with huge pressures from war and welfare piling up in all nations, the Bretton Woods agreement did indeed break down. The United States became a net importer of goods, meaning that its outward gold shipments would only increase, depleting stockpiles that secured the soundness of the currency. Financial managers, bankers, and economic planners were powerless to stop this simply because the international agreement required that international accounts be settled in gold.

President Richard Nixon (2nd-L) poses at the White House in Washington, with four government officials he named as his economic “Quadriad” on Jan. 23, 1969. (L-R) Chairman William M. Chesney Martin Jr., of the Federal Reserve Board; Nixon; Secretary of the Treasury David M. Kennedy; Budget Director Robert Mayor and Chairman Paul McCracken of the Council of Economic Advisers. AP Photo/ Harvey Georges

Richard Nixon was the president who had to deal with the crisis once the gold outflows became near terminal. On Aug. 15, 1971, Nixon broke the whole international monetary order by suspending gold convertibility. The United States would no longer ship its gold in exchange for goods. This move shocked the world. Improvising, a new agreement was reached 18 months later. With the Smithsonian Agreement, a new global system of fiat money was born. There would be a market for currencies to trade against each other but with absolutely no tether to gold.

The dollar retained its global supremacy. Any economist schooled in both trade theory and monetary theory (fewer and fewer are) could have predicted what would happen. The U.S. industrial base would be gradually dismantled as nations discovered how their lesser-valued currencies gave them an advantage as exporters. The United States would retain its exporter status on natural resources but manufacturing was surely doomed.

It was also easily predictable that the United States would begin running trade deficits with essentially everyone because the market for dollars was international and settlement was no longer a necessary feature of the system. Japan and then China figured out the new metrics of international trade, and policymakers sat by and watched with astonishment how one American industry after another evaporated: pianos, watches, household electronics, apparel, textiles, steel, cars, tools, ships, and on it goes.

The math of the situation made this inevitable. International trade in the days of the gold standard tended to yield what David Ricardo called the Law of One Price. Gold settlement equilibrated prices and wages internationally in the same way they did domestically. With the Smithsonian Agreement, the disequilibration would be permanent and further worsening to the disadvantage of the country hosting the world’s most valuable and most-used currency.

It should have been obvious that such a situation was not sustainable. It was Donald Trump who called it out alongside his suggested remedy of old-world tariffs. The theory was that by adding an import tax, the manufacturing disadvantage of the dominant nation would be remedied—a prescription that had never been deployed before simply because these conditions have never before prevailed.

The architects of the Bretton Woods system are today likely rolling in their graves to see the global system of trading revert to walled gardens of tariffs, zones, and regional supply lines, alongside the inevitable tensions that such a system produces. But keep in mind: the system they set up could result in no other. By attempting to gamify a gold standard without the discipline that comes from domestic convertibility, they made the present world inevitable. That it took 70 years to get here makes it no less part of the logical and political trajectory any intelligent observer could have foreseen.

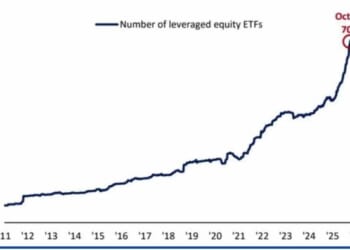

The fiat money system was the shepherd of the breakdown of world trade, in addition to fueling astonishing levels of leverage, debt, inflation, and financial irresponsibility all around. This sad story points to an eternal truth. You cannot ever trust governments with the production and management of money. When they are not abusing the system to serve themselves, they are mismanaging it to make it untrustworthy for everyone else to use.

Loading recommendations…