We’re bringing together the brightest minds in energy policy for Dispatch Energy: The Current State, a symposium where we’ll discuss the future of energy innovation.

Join Steve Hayes, Jonah Goldberg, and more of your favorite Dispatch authors on Wednesday, March 11, in Dallas, Texas. We’ll be announcing more guests in the coming weeks, so stay tuned. Tickets are limited—and we’re giving premium and lifetime members early access. Get your tickets today.

Welcome to Dispatch Energy! Electricity regulation is not where transformative change usually arrives in dramatic fashion. It proceeds through hearings, rate cases, and line items on monthly bills. A routine regulatory proceeding can thus become a quiet referendum on AI, data centers, and the future of the power grid. Following that shift reveals how rapid, uncertain electricity demand collides with institutions built for slow, predictable change, and why seemingly technical disputes over regulated rate structures and cost recovery mask deeper governance problems. When technological progress demands large, irreversible infrastructure investments, the central question is not whether the grid can expand, but who pays for it and who bears the risk when expectations about the future prove wrong.

Who Pays for the AI-Driven Grid?

The hearing in the summer of 2024 was supposed to be routine. A state public utility commission had convened to review a standard rate case: covering rising fuel costs, smart grid investments, storm hardening, labor expenses, and perhaps a modest adjustment to the utility’s allowed return on equity. The script was familiar. Utilities emphasized the need for reliability. Consumer advocates pushed for affordability. Commissioners asked whether the proposed rate increases were prudent and justified.

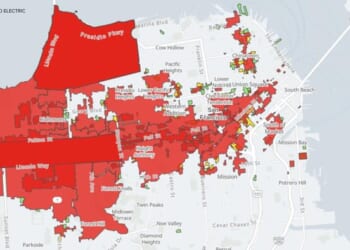

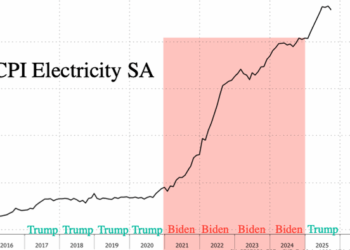

Then the public comments drifted off script. Customers complained that their electricity bills had risen even though their usage had not. Commissioners asked why infrastructure spending seemed concentrated in a handful of counties, and why cost trackers embedded as line items on bills had surged. Utility officials began talking about new generation, transmission upgrades, data center tariffs, minimum bills, and long-term contracts for “large load customers.”

What was supposed to be a backward-looking accounting exercise, rooted in a century of regulatory practice, quietly turned into a debate about AI, data centers, and who should pay for a rapidly expanding grid.

This scenario was not a hypothetical or isolated episode. Beginning in 2023, the electric utility company AEP Ohio imposed substantial barriers to new data center interconnections in the Columbus region after forecasting an unprecedented surge in electricity demand that it argued would overwhelm existing infrastructure. The utility paused new service requests in March 2023, freezing more than 50 proposed projects representing over 30 gigawatts of demand, and later replaced that pause with a data center tariff approved in mid-2025.

That tariff requires large data centers (with loads of 25 megawatts or more) to sign 12-year take-or-pay contracts (meaning they pay for a set amount even if they use less) covering at least 85 percent of the system capacity reserved for the data center, along with exit penalties and mandatory load studies. AEP justified these provisions as necessary to protect existing customers from the costs of long-lead investments in generation and transmission. Subsequent revisions to its own demand forecast—from roughly 30 gigawatts to about 13—fueled criticism that the original projections overstated the magnitude of demand growth and locked in restrictive terms under deep uncertainty. The result has been a chilling effect on data center investment and a regulatory framework tilted toward protecting existing ratepayers.

This is how AI enters the electricity system in practice: not through a single, deliberate policy choice, but sideways—through rate cases, interconnection disputes, and tariff design decisions built for a very different economic environment.

In my previous newsletter, I focused on the collision between surging AI-driven electricity demand and a grid designed for slower, steadier growth. Data center construction occurs on roughly an 18-month horizon; power plants, transmission lines, and substations take years to plan, permit, and construct. This timing mismatch creates real risks for reliability and resource adequacy and cannot be solved by efficiency gains alone.

The hearing room reveals the next layer of the problem. Even when infrastructure can be built in principle, it will not be built smoothly or at scale unless regulators decide who pays for it, and who bears the risk when expectations turn out to be wrong.

Risk and cost allocation.

Electricity infrastructure is capital-intensive, long-lived, and largely irreversible. Once generation, transmission, or distribution assets are placed into service, their costs are recovered over decades. Building infrastructure is therefore both a technical judgment about capacity needs and a commitment to a particular future under uncertainty.

The regulatory framework governing U.S. electric utilities exists to manage that commitment. Utilities operate under rate-of-return regulation, rooted in natural monopoly theory. Electricity networks involve high fixed costs and declining average costs, making it inefficient to build duplicate infrastructure networks (or so the theory goes). States therefore grant utilities monopoly service territories and impose obligations to serve, subjecting them to price and investment regulation in exchange.

Rate-of-return regulation codifies this bargain. Utilities recover prudently incurred operating costs and earn a regulated return on invested capital, known as the rate base, intended to reflect their opportunity cost of capital. Customer rates are set in a way that allows utilities to raise enough revenue to cover both types of costs gradually over time.

Under conditions of incremental, predictable demand growth, this system works tolerably well. Forecast errors are modest. Investments benefit broad classes of customers. Costs diffuse across millions of power bills. The political economy remains quiet, relatively.

The hearing that unexpectedly became about AI followed this logic exactly. The utility was not asking to raise prices at will. It was proposing investments and seeking assurance that, if deemed prudent, those costs and returns would be recoverable. The commission was not setting market prices; it was deciding how the costs of preparing for future demand should be allocated.

AI-driven data center growth disrupts the assumptions that made this system stable. Demand arrives faster than planning cycles can absorb. Load is geographically concentrated. Commitments are made before the durability of demand is known. Individual investments—substations, transmission upgrades, new generation—are large enough to be visible on monthly bills. Utilities are therefore asked to invest before uncertainty resolves, even though the regulatory model presumes demand will materialize broadly and persistently.

When that presumption holds, building ahead of need is prudent. When it does not, it creates stranded-cost risk.

What makes this moment qualitatively different is that utilities and regulators are not merely facing risk; they are confronting Knightian uncertainty. Risk describes situations where outcomes are uncertain but probabilities can be estimated—fuel price volatility, weather variation, incremental load growth, etc. Knightian uncertainty, on the other hand, arises when future states of the world themselves are not well defined and probabilities cannot be assigned with confidence. The scale, location, and persistence of AI-driven data center demand fall squarely into this category. Utilities must decide whether to build long-lived infrastructure today without knowing whether specific facilities will operate for decades, self-supply, relocate, or disappear. Yet once those investments are made, they cannot be undone.

Rate-of-return regulation was designed to manage risk under relatively stable growth, not to allocate the costs of irreversible investments made under deep uncertainty. As a result, questions of who pays become unavoidable.

Once an asset enters the rate base, its costs remain embedded in customer bills for decades. The mismatch between fast-moving demand and slow-moving cost recovery turns timing mismatch into a problem of risk allocation. Someone must front the capital. Someone must bear the risk of building too much or the wrong thing. Someone must pay if demand shifts or bypasses the grid. In regulated power systems, those choices are made through regulatory structure, not markets.

Scarcity has not disappeared; it now manifests differently due to the distinctive features of data center demand. Efficiency gains in AI computation do not eliminate the need for long-lived infrastructure. Transmission corridors cannot be conjured instantly. Substations cannot be scaled elastically. Distribution networks were not designed for sudden, concentrated load growth. Data centers are therefore a stress test, revealing where scarcity actually exists and forcing a choice about insurance. Someone must underwrite the future.

At this point, abstraction gives way to regulatory mechanisms. Cost-causation principles ask whether customers who drive new costs should bear them. Beneficiary-pays principles ask whether costs align with benefits that accrue over decades. Rate design, interconnection charges, minimum bills, and exit fees determine whether capital is recovered upfront or socialized over time. These tools are the mechanisms through which regulators decide who insures whom against uncertainty.

Capital bias and institutional limits.

Rate-of-return regulation also shapes incentives. Because utilities earn returns on capital investments but not on operating expenditures, the system encourages capital deployment such as building network infrastructure. This capital bias supported the universal electrification and grid expansion of the 20th century, but is now in tension with a digital grid in which, for example, digital technologies can squeeze better capacity utilization out of the existing network at a lower cost than building more wires.

Under rapid, uneven demand growth, the same incentive structure becomes fragile. Utilities face pressure to build to meet their regulatory requirements to serve all customers in their geographic service territory, knowing that prudent capital is likely to be recovered. Regulators face pressure to approve investments to avoid reliability failures. Less capital-intensive alternatives—contractual flexibility, supply arrangements with non-utility parties, demand flexibility—receive less attention because they do not expand the rate base.

The asymmetry between utilities and data centers sharpens this fragility. Data centers are mobile and capital-flexible. Utilities manage immobile assets with recovery horizons measured in decades. When large customers retain the option to exit while infrastructure costs remain embedded in the system, risk shifts toward captive customers, fueling political backlash.

Governing technological change.

Rising residential bills, special data center tariffs, moratoria, and contentious rate cases are signals that institutions built for slow, predictable change are being forced to absorb rapid, uncertain transformation.

AI’s electricity footprint forces a deeper confrontation with how we invest in long-lived assets under deep uncertainty. Power systems can evolve, but can the institutions that govern them adapt fast enough to allocate risk transparently and legitimately?

Who pays for the grid is how societies decide who bears the costs of progress. The rate case hearing that turned into a deliberation on the rise of AI was not an aberration. It was the future arriving through familiar institutions to ask unfamiliar questions.

Lawsuit: Ban on oil drilling is unconstitutional

For generations, the Morgan family has owned mineral rights on oil-rich land in Santa Barbara County. But in 2024, California banned oil and gas drilling within 3,200 feet of “sensitive receptors,” which includes most places where the public works, lives, and plays. The Morgans can no longer develop their oil reserves. This week the Morgans filed a federal lawsuit, arguing California’s drilling ban violates the Fifth Amendment.

Policy Watch

- Last month, the Midcontinent Independent System Operator (MISO) approved a major expansion of the Midwest and Southern electricity grid. MISO is the regional organization that manages the high-voltage transmission lines connecting generators to customers across 15 states from the Dakotas to Louisiana. The plan authorizes 432 projects costing more than $12 billion, a significant jump from routine maintenance to deliberate grid expansion. These projects will build new long-distance power lines, substations, and upgrades to handle three growing challenges: surging electricity demand, large numbers of new power plants awaiting connection, and older plants shutting down. A notable feature is a set of “expedited” projects designed to move faster than usual. These respond to what planners call “emerging load,” large electricity users like data centers and factories that are arriving much faster than the slow, steady demand growth utilities have historically planned for. The plan also locks in how costs will be shared: Utilities and their customers across different regions will split the bill based on the idea that everyone benefits from a more reliable grid. Once construction starts, this cost-sharing arrangement is hard to change. This decision matters beyond infrastructure spending. It determines which power plants can connect to the grid, how well the system will handle extreme weather, and how electricity markets develop over the next decade. In effect, MISO’s transmission plan shapes the future structure of the regional power system.

Innovation Spotlight

- Verrus Data is a U.S. data center developer that’s rethinking how these facilities use power. Instead of treating electricity as a simple input, Verrus integrates energy systems directly into its data centers. The company’s facilities combine advanced power management, large-scale batteries, and a campus-wide electrical network to create what it calls “grid-aware, carbon-aware, compute-aware” buildings that maintain high reliability while actively helping the electric grid. Verrus builds modular data centers designed for AI and cloud computing with 99.999 percent uptime. But unlike traditional data centers that draw power constantly, these facilities can also support the grid during stress periods when demand is high, according to the company. When utilities send a signal, Verrus says its centers can reduce their power draw by up to 100 percent within a minute, switching seamlessly to battery power without disrupting their computers. This approach differs from conventional data center design. By making its facilities flexible rather than rigid electricity consumers, Verrus aims to reduce strain on the grid, help new projects connect faster (by easing interconnection bottlenecks), and tap into existing grid capacity that would otherwise go unused—all while meeting sustainability targets and customer expectations.

- MIT researchers describe artificial intelligence as a powerful tool for managing the power grid, especially as operators struggle to balance supply and demand with more wind and solar energy in the mix. AI can analyze historical patterns and real-time data to produce much more accurate short-term forecasts of how much power these variable sources will generate. This could help grid operators make better decisions about which power plants to run—decisions that can be both economically smart and environmentally beneficial, at lower cost than current methods. AI could potentially also solve the difficult optimization problems grid operators face daily: which generators to turn on, how much power each should produce, when to charge or discharge batteries, and how to adjust flexible demand. AI can handle these calculations faster and more effectively than traditional approaches, potentially in real time. Beyond day-to-day operations, researchers are exploring AI for long-term planning—speeding up simulations of large grid networks to design future infrastructure—and for predictive maintenance, where AI can identify unusual patterns that signal equipment problems before they cause outages. This research highlights AI’s practical benefits for grid control and forecasting, while emphasizing that models must account for the grid’s physical constraints to ensure the system remains reliable and resilient.

Further Reading

- For two years, I directed the Energy Technology, Regulation, and Market Design Working Group at the American Enterprise Institute, and in 2025, we published our final report: Innovating Future Power Systems: From Vision to Action. The report’s central argument is that America’s century-old centralized utility model—built around regulated monopolies delivering power from large plants through exclusive franchises—has become outdated. Digital technologies and distributed energy resources now enable a more dynamic system where consumers can participate actively rather than remain passive recipients. The report recommends regulatory reforms that encourage competition, embrace dynamic pricing, support microgrids and virtual power plants, and remove barriers to technologies like vehicle-to-grid charging. The underlying philosophy: trusting markets and innovation to solve energy challenges rather than relying exclusively on centralized planning. The goal is an abundant, clean energy future where technology enables both environmental progress and consumer empowerment.

Pacific Legal Foundation has been fighting for freedom since 1973. We sue the government on behalf of farmers, fishermen, teachers, nurses, and entrepreneurs—Americans from every corner of the country and from every walk of life—and we win.