Life, Liberty, Property #132: A Potentially Historic Central Bank Reform

Forward this issue to your friends and urge them to subscribe.

Read all Life, Liberty, Property articles here, and full issues here and here.

- A Potentially Historic Central Bank Reform

- Video of the Week: Why Davos Is Wrong About the Future: James Taylor Responds

- Congress Considers Bill to Limit Freedom to Bring Lawsuits

A Potentially Historic Central Bank Reform

“Economists, investors, and executives” are applauding President Donald Trump’s choice of Kevin Warsh to be the next chairman of the Federal Reserve. So said The Wall Street Journal on Friday. The markets immediately confirmed that assessment, in interesting ways.

Warsh, a former member of the Federal Reserve Board, is seen as a safe choice for Fed chair because he is more hawkish on the U.S. dollar than any of his recent predecessors. The Wall Street Journal summarized those sentiments on Friday:

Some market participants see Warsh as a relatively safe option, given his Fed experience and his track record as an inflation hawk, or supporter of tight monetary policy. That could make him more resistant to calls from the administration to slash interest rates, a prospect that helped the dollar and hammered precious metals Friday.

Trump, who settled on Warsh after a monthslong search, said he had “no doubt that he will go down as one of the GREAT Fed Chairmen, maybe the best.”

Economists, investors and executives generally welcomed the pick. Mark Carney, the Canadian prime minister and former central banker, called him a “fantastic choice.”

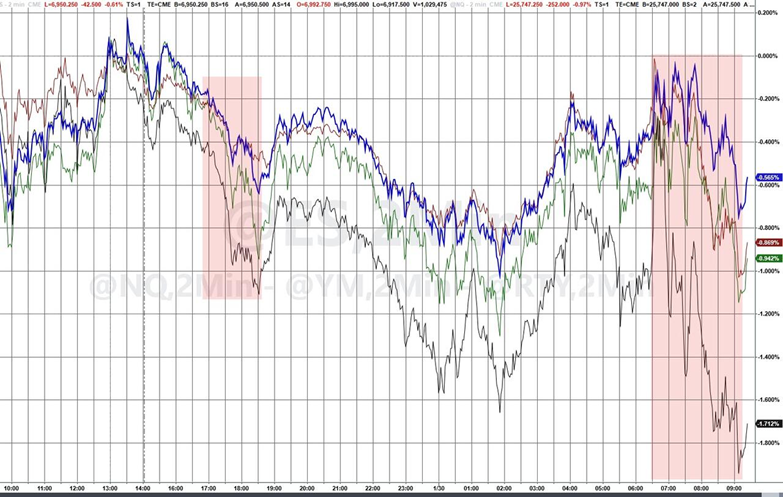

Multiple asset classes decreased in value after the announcement on Friday, with gold and silver receding by 12 percent and 25 percent from their peaks by midday. That means, of course, that investors have more faith in the U.S. dollar than they did before the announcement.

Two charts from ZeroHedge illustrate it well:

Source: ZeroHedge

This was the biggest rush out of those two precious metals in nearly a half-century, and a one-day record drop in the dollar price of gold futures, The Wall Street Journal noted:

A violent selloff Friday sent silver prices crashing and gold futures to their biggest one-day dollar decline on record, the latest twist of wild trading that has left precious metals swinging like meme stocks.

For months, a gravity-defying rally had pushed gold and silver prices to all-time highs, enticing speculators and sparking fears that investors the world over were losing faith in traditional currencies like the dollar. Starting Thursday night, the air finally came out.

The declines began around the time reports suggested that President Trump would nominate former Federal Reserve governor Kevin Warsh to succeed Jerome Powell as chair of the central bank. Warsh historically has been more concerned with higher inflation than slower growth, soothing Wall Street fears that the Fed would succumb to Trump’s push to lower interest rates.

Investors worried about the future of the dollar in an era of higher inflation had piled into precious metals in recent months, powering what has become known on Wall Street as the debasement trade.

Translation: once they realized that Warsh would probably be the next Fed chair, people traded gold and silver for dollars, after having done the opposite for months on end.

Meanwhile, U.S. equities fell in value:

Source: ZeroHedge

Stock prices moved lower because investors perceived that the Federal Reserve under Warsh will resist a return to expansive monetary policy, which juices equity prices well beyond the fundamental value indicated by their expected real, inflation-adjusted returns.

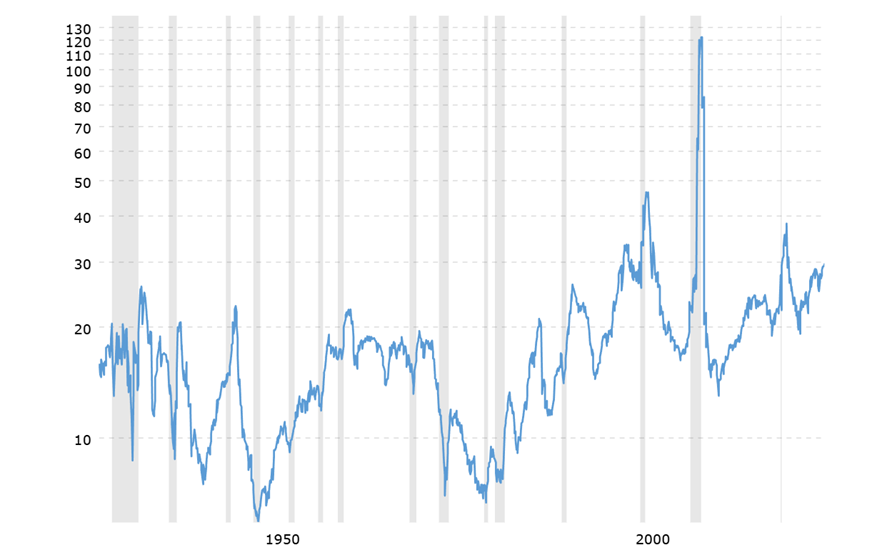

Stock prices still have a very long way to go to get down to somewhat plausible price-earnings ratios:

S&P 500 PE Ratio – 90 Year Historical Chart

Trailing twelve-month S&P 500 price-to-earnings ratio, 1926-present

Source: Macrotrends

President Trump will probably be quite upset if stock values fall toward their real values, as his political opponents will be able to characterize it as a bad sign. In fact, however, it would be the opposite in the present case, as the recent high stock prices reflect excessive Fed-created money going to the best place it can find, not the stocks’ underlying real values in terms of expected dividends and the like.

While pushing stock prices slightly toward their real values, the expectation of better monetary discipline raised demand for the U.S. dollar:

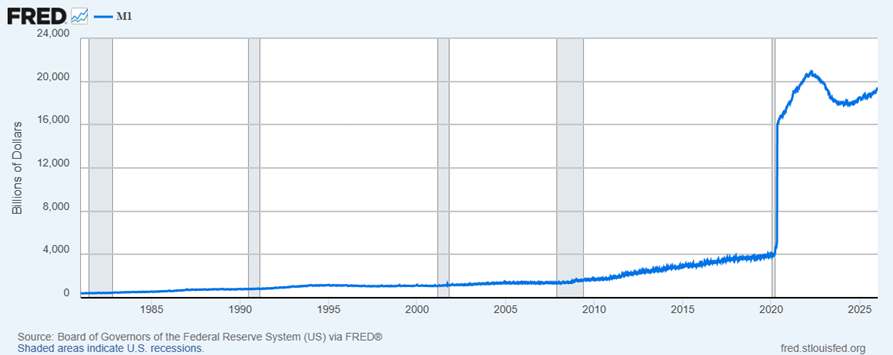

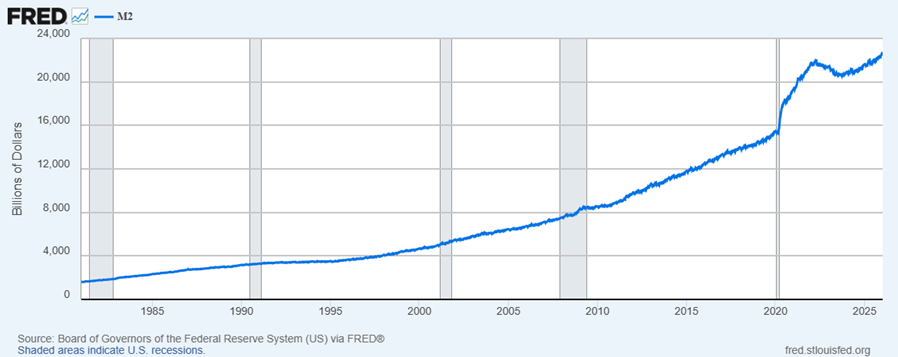

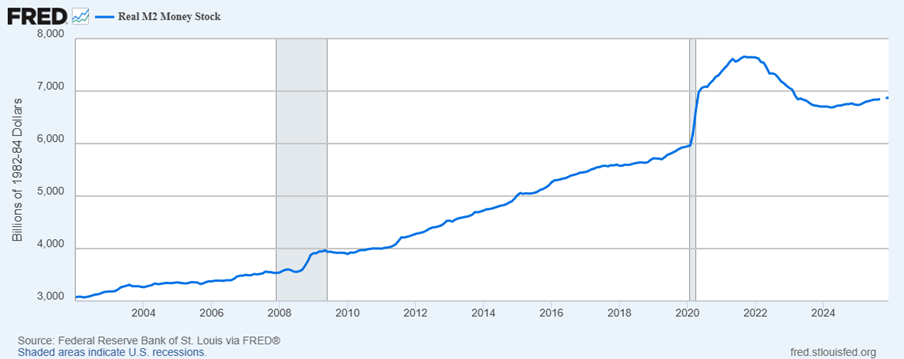

A reliable dollar is a strong dollar and is a very good thing. The first reactions to the Warsh nomination indicate that those in the know believe he will slow the money supply expansion of 2010-2018 and the pandemic-era money explosion of mid-2020 through mid-2022:

Although these changes are, at this point, just one-day corrections of positions taken in light of prior (awful) Fed policies, they indicate a good understanding of how much damage the Federal Reserve can do and has done in recent years. Market participants are confirming that the country urgently needs a serious change in thinking at the Fed.

Warsh will be taking over the Fed for a president who is very concerned about interest rates and the money supply and regularly calls for looser monetary policy. Warsh is not a loose-money addict. He is, however, a strong proponent of free markets and lower regulation, in full accord with Trump’s opinions on the economy and government action. Notably, Warsh strongly disagrees with the Fed’s obsession with the Phillips Curve, in obedience to which the central bank invariably tanks the economy whenever wages start to rise and then unleashes inflation when workers’ salaries stagnate, as Warsh wrote in The Wall Street Journal last fall:

[I]nflation is a choice, and the Fed’s track record under Chairman Jerome Powell is one of unwise choices. The Fed should re-examine its great mistakes that led to the great inflation. It should abandon the dogma that inflation is caused when the economy grows too much and workers get paid too much. Inflation is caused when government spends too much and prints too much. Money on Wall Street is too easy, and credit on Main Street is too tight. The Fed’s bloated balance sheet, designed to support the biggest firms in a bygone crisis era, can be reduced significantly. That largesse can be redeployed in the form of lower interest rates to support households and small and medium-size businesses.

Note that Warsh does not suggest that high interest rates are the road to economic Heaven, writing instead that “credit on Main Street is too tight.”

Warsh has that exactly right, as regular readers of this newsletter have heard many times. Lower interest rates (which tend to expand the money supply) countered by reduction of the Fed’s balance sheet (which is indeed bloated and inflationary) are exactly the policy mix that I have been calling for. Instead of punishing the American worker whenever good economic times arrive, the central bank should stick to its job of fostering sound money and let businesses, their customers, and their workers decide how much the latter should be paid.

For Warsh, the fundamental things apply, as the song goes:

America’s real comparative advantage is its workers of all stripes—everywhere from factory floors to drilling rigs, corporate cubicles to garage startups—who devise new ways of doing business. The result: a revitalized nation of doers, risk-takers, and, in entrepreneur Marc Andreessen’s simple framing, builders.

Perhaps the most underappreciated characteristic of the Trump administration is its admiration for individual achievement. Treating people based on their merits rather than their status or sensibilities is the renewed American credo. The affinity group that matters most is that of our fellow Americans.

Wall Street and Silicon Valley are booming, and U.S. workers are finally getting a step-up in their real take-home pay. Even so, the benefits of the American juggernaut are yet to be realized fully. Among the chief obstacles is the Fed. The world is moving faster, yet the Fed’s leaders are moving slower. They appear stuck in what Milton Friedman called “the tyranny of the status quo.”

Warsh has the right perspective on the important issues for the central bank. If the Senate confirms his appointment (as is quite likely) and he sticks to his principles, Warsh will surely hear some tart comments from Trump at times. In addition, those who are now saying good things about him were largely in favor of the Fed’s awful monetary manipulation of the past three decades in particular and will complain of impending disasters if Warsh implements the policies he favors.

I believe that both those complaints will turn out to be wrong. And that will turn out to be very, very right for the U.S. economy and the American people.

Sources:The Wall Street Journal; ZeroHedge; The Wall Street Journal

Video of the Week

In this keynote address from Day 2 of the World Prosperity Forum in Zurich, James Taylor, president of The Heartland Institute, explains why a counter-forum to Davos was urgently needed—and how it came together in a matter of weeks. Held concurrently with the World Economic Forum (WEF), the World Prosperity Forum was created to confront the WEF’s centralized, collectivist, and alarmist worldview.

Congress Considers Bill to Limit Freedom to Bring Lawsuits

A purported lawsuit abuse prevention bill now before Congress “sounds reasonable” but “doesn’t do what its advocates claim,” writes my Heartland Institute colleague Cameron Sholty at Real Clear Policy.

Although presented as fostering consumer protection and legal transparency, the Protect Third Party Litigation Funding from Abuse Act would further strengthen powerful companies by removing an important means of holding them responsible for their actions, Sholty writes:

Instead of preventing lawsuit abuse, it quietly takes away one of the only tools underfunded plaintiffs have to challenge powerful institutions. And in doing so, it ends up protecting the very corporate behavior conservatives say they’re fed up with.

The bill, sponsored by Rep. Darryl Issa (R-CA), would require the exposure by name of anyone who would share in the proceeds of a successful lawsuit:

… a party or any counsel of record for a party shall disclose in writing to the court and all other named parties to the civil action the identity of any person (other than counsel of record) that has a legal right to receive any payment or thing of value that is contingent in any respect on the outcome or proceeds of the civil action or a group of civil actions of which the civil action is a part … .

The only exceptions allowed are loan repayments, attorneys’ fees (of course!), and grant reimbursements.

In third party litigation funding, an individual, company, or other organization gives a plaintiff or a law firm money to cover the costs of a proposed lawsuit. For providing the advance funding of the lawsuit, the third-party funder receives a share of any judgment or settlement the court may award. If the plaintiff loses the case, the funder gets nothing.

Lawsuits can be very expensive undertakings, and the expense gives big corporations and wealthy individuals an obvious advantage by regulating access to the courts. Third party funding gives non-wealthy people a chance at pursuing redress of wrongs through civil action in the courts.

The “abuse” that Issa’s bill proposes to end is the practice of using these arrangements as investments, in which hedge funds or speculators support lawsuits in hopes of a positive return on that investment.

Far from being a scheme for lawsuit abuse, third-party litigation funding democratizes access to the courts, Sholty argues:

Third-party litigation funding gets painted as some kind of predatory hedge fund scheme, fueled by foreign money and greedy speculators. It’s a tidy story, but it’s not the truth. In the real world, litigation funding often allows individuals, small businesses, and nonprofits to bring legitimate claims against corporations with unlimited time and money—and that can win simply through attrition.

That imbalance is real and it matters.

When one side has a billion-dollar balance sheet and an army of lawyers on retainer, Lady Justice becomes a platitude rather than a bulwark against special interests captured by ideology. Third-party funding doesn’t rig the game. It makes it possible to play at all.

By creating a threat against people who want to bring lawsuits, Issa’s bill would transfer even more power to big corporations and the ultra-wealthy. Sholty writes,

[L]itigation is expensive, often brutally so,” Sholty writes. “Without outside funding, many people simply can’t afford to challenge discrimination, retaliation, or coordinated corporate behavior, no matter how strong their case is.”

Big corporations will still fund their defenses without blinking. They’ll still bury opponents in procedure and delay. What disappears is the credible threat that a smaller player might actually make it to the finish line.

The notion that this practice is a dangerous “abuse” is a canard. A 2022 report by the U.S. Government Accountability Office confirms that the funders of these lawsuits are careful about which suits to support, and that they make sure not to interfere in the conduct of the cases:

All the commercial funders we spoke with said that before deciding whether to fund a client, they undertook a due diligence process that evaluated several factors. Funders most commonly said they considered the merits of a potential case (six of seven funders), the potential client’s legal team (five of seven funders), and the ability of the defending party to pay (five of seven funders). Most funders said they only fund a small percentage of the total requests for funding they receive after conducting due diligence. For example, data from two funders show that about 5 percent of formal requests for funding ultimately resulted in a funding agreement. Similarly, Burford Capital reported that in 2020 only 4 percent of requests for funding resulted in financing agreements. Funders select the most meritorious cases to fund because they only receive returns when claims are successful.

All of the commercial litigation funders we interviewed said they did not make any decisions about litigation strategy for the cases they fund through TPLF arrangements.

Those considerations place a natural, economic limit on this type of funding and the actions of potential donors. The GAO study indicates that although third-party litigation funding is growing in popularity, “no comprehensive estimate of total market size exists because publicly available data on the market are limited.” It is, however, certainly a very, very small percentage of the total number of lawsuits.

The option of third-party funding is an obvious benefit to people who cannot afford to go to court to get redress for injuries. Issa’s bill would limit regular people’s access to the courts by intimidating people who want to help others bring lawsuits and share in the outcome, Sholty notes:

Litigation funding only works if it’s confidential. If funders know their involvement will automatically be handed to opposing counsel, they’ll walk away. Not because the cases are weak, but because the risk calculus changes. The end result isn’t better justice, but fewer cases.

The threat in Issa’s bill, which is surely intentional, is that exposure of the names of people funding lawsuits would make them vulnerable to harassment, retaliation, boycotts, character assassination, public bullying, social-media mob antagonism, debanking, demonetizing, physical attacks, and other abuse from people who oppose the lawsuit.

Forcing exposure of lawsuit funders is an obvious blackmail tactic: support an unpopular lawsuit, even if it is thoroughly justified, and you can be subjected to a public hate campaign.

There is no other reason for a law to require public disclosure of these funders’ names. The goal is to reduce or eliminate this type of funding.

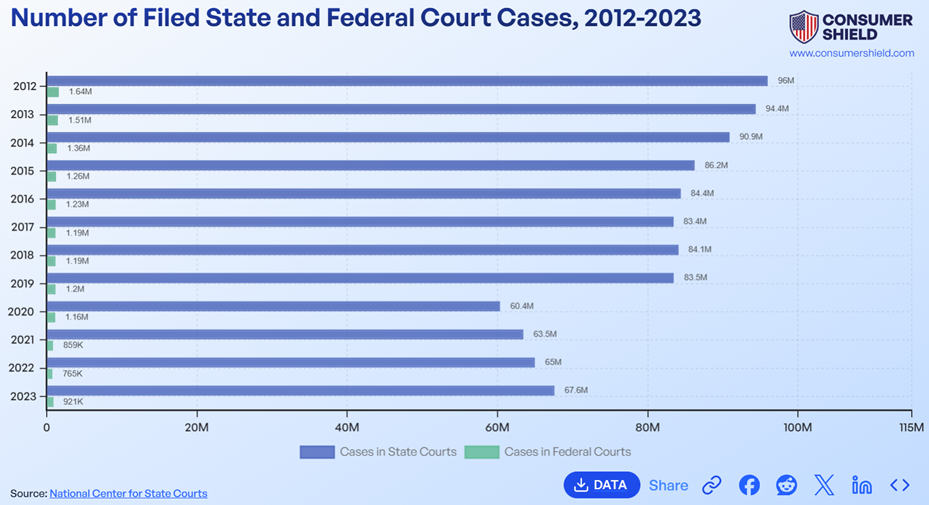

These cases are not overloading the courts by any means. The civil courts’ caseload, though certainly unnecessarily high, has eased in recent years, with the third-party litigation funding option in place, so that is not a valid reason for the proposed legislation. The number of lawsuits per year in the United States on the state and federal levels has declined by about one-third since 2012:

Source: Consumer Shield

Few of these lawsuits go to trial, instead being settled beforehand or being dismissed for other reasons, a trend that was in place long before 2012, as Yale University law professor John H. Langbein noted in The Yale Law Journal in that year: “Since the 1930s, the proportion of civil cases concluded at trial has declined from about 20% to below 2% in the federal courts and below 1% in state courts.” Those numbers are still true today. Third-party litigation funding is not burdening the courts, even as it increases people’s access to the civil justice system.

In addition to Issa’s legislation being unnecessary in practical terms, states already have the authority to implement rules on the practice (and federal lawsuits are a very small amount of total civil litigation in the country, as noted above): “As of July 2025, seven states—Indiana, Kansas, Louisiana, Montana, Oklahoma, West Virginia, and Wisconsin—have regulations governing litigation funding,” the Washington Legal Foundation notes.

The fact that so few states have bothered with the issue shows that the vast majority of legislators around the country do not consider third-party litigation funding to be a problem, as does the limited nature of these state laws in comparison with what Issa’s legislation would do.

Third-party litigation funding by investors is not an abuse. The real abuse would be in preventing people from donating money that ensures “the courthouse doors aren’t only open to the wealthy,” as Sholty puts it:

Supporters say the bill prevents abuse. But abuse of whom? There’s little evidence that litigation funding drives frivolous lawsuits. Funders aren’t charities. They don’t throw money at bad cases. They conduct deep due diligence and only back claims they believe can win.

The high cost of legal representation limits access to the courts. Civil lawsuits, moreover, are a vital element of a free society. Access to the courts gives people a chance to hold the powerful responsible for harms they might do. Restricting that access transfers more power to the powerful. That is an abuse we definitely do not need.

Sources: Real Clear Policy; HR 7105—119th Congress; Government Accountability Office; Washington Legal Foundation

Important Heartland Policy Study

‘The CSDDD is the greatest threat to America’s sovereignty since the fall of the Soviet Union.’

Contact Us

The Heartland Institute

1933 North Meacham Road, Suite 559

Schaumburg, IL 60173

p: 312/377-4000

f: 312/277-4122

e: [email protected]

Website: Heartland.org