Donald Trump, Progressive Democrat?

The president’s embrace of economic leftism has been brewing for a while, but one frantic week last month showed clearly that we’re not dealing with “first term Trump” anymore. In the span of just a few days in January, he announced three policies straight out of progressive Democrats’ playbook:

- On January 8, Trump promised to “immediately” take steps to ban large institutional investors from buying single-family homes and followed up with an executive order targeting these firms a few days later. As CNN reported at the time, “Several Republican lawmakers cheered the proposal and said they would introduce legislation” to enact it, but it’s been Democrats who have pushed similar legislation for years. In December 2023, for example, Sen. Jeff Merkley and Rep. Adam Smith introduced the “End Hedge Fund Control of American Homes Act” forcing these firms to sell off their residential holdings, and earlier that year Sens. Sherrod Brown, Elizabeth Warren, Sanders, and others proposed to eliminate tax deductions for investors owning 50 or more homes. This year, progressive Rep. Ro Khanna reintroduced the Stop Wall Street Landlords Act, which would similarly disfavor institutional investors.

- The very next day, Trump reiterated his campaign pledge to cap credit card interest rates at 10 percent and urged Congress to enact a law doing so. Once again, such proposals have long been championed by Democrats, such as Sanders and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, both of whom offered bills last year enacting a 10 percent cap for five years. Shortly after Trump renewed his call for a cap, Warren confirmed that he had called her to discuss the idea, and that she had urged him to “fight for it in Congress.

- The day after that, Trump directed government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to purchase $200 billion in mortgage bonds, which he claimed “will drive Mortgage Rates DOWN.” Bill Pulte, director of the Federal Housing Finance Agency and chairman of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, later confirmed that the GSEs “will do the purchases.” Unlike the above policies, it doesn’t appear that progressives have proposed this exact move, but they have long advocated using the GSEs to actively manipulate mortgage and refinancing markets to subsidize homebuying. In 2020, for example, Sens. Brown, Warren, Brian Schatz, and other Democrats urged the FHFA to use Fannie and Freddie to make moves to reduce low-income borrowers’ mortgage payments. Bills encouraging more GSE intervention in the housing finance market have also been offered by Brown, Rep. Maxine Waters, and other Democrats.

So, that makes three “affordability” policies in three days, all of which come from the progressive left—and, in fact, are arguably more interventionist than what the “radical” Democrats have proposed.

The policies aren’t, however, a radical shift for Trump.

Indeed, several previous Trump “affordability” efforts have had a similar leftist bent. Last November, for example, Trump directed Justice Department to investigate large U.S. meatpackers for “Illicit Collusion, Price Fixing, and Price Manipulation”—a move eerily similar to former President Joe Biden’s accusations of meatpacker “profiteering” in his 2022 State of the Union and Warren’s broader attempts to blame corporate “greedflation” for high food prices. In May, meanwhile, Trump signed an executive order directing the Department of Health and Human Services to regulate U.S. drug prices by benchmarking them against other countries in the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development—a plan that mirrors progressive proposals to peg U.S. drug prices to the median in Canada, the U.K., France, Germany, and Japan.

Other recent Trump proposals that aren’t linked directly to “affordability” issues are also decidedly leftist. Democrats have, for example, long sought to regulate CEO pay and restrict corporate stock buybacks (on the erroneous theory that buybacks depress investment/wages), and Trump’s January 7 executive order does that for major defense contractors. His accompanying Truth Social post that “no Executive should be allowed to make in excess of $5 Million Dollars” could’ve been written by Bernie himself. Trump’s tariff rebate checks, meanwhile, are just the kind of tax-and-spend redistributionism that Democrats have long championed—and that Joe Biden delivered in the American Rescue Plan. And, as we’ve discussed, Trump demanded that the One Big Beautiful Bill Act include several complex carve-outs—for tips, seniors, etc.—that contradict longstanding conservative tax principles and are usually favored by Dems instead.

Clear, Simple, and Wrong

Trump was never a doctrinaire Reaganite supply-sider, of course, but his embrace of domestic economic policies championed by U.S. progressives is the clearest evidence yet that the “horseshoe” theory of politics—i.e., that the extreme left and extreme right have more in common with each other than with the moderate center—is alive and well in the United States. The similarities have been clearest on trade, where both the far left and far right uniformly disdain “globalization” and the “elites” who supposedly use it to profit at The People’s expense. But we now see the same parallels in domestic economic policy, too—both in the details and the script that each policy follows: target common enemies and offer easy solutions to complex problems—solutions that don’t actually work and, in fact, can often make things worse for the very people that they claim to be helping.

Trump’s “affordability” proposals follow the “horseshoe economics” script to the letter. Smacking institutional investors (aka “Wall Street”) might make for a great populist soundbite, but as housing expert Jay Parsons explained at considerable length (and as we’ve discussed here at Capitolism), there’s simply no good case for the ban, which would likely harm rental markets yet have a minimal effect on the supply of single family homes—even in investor-rich markets. (My Cato Institute colleague Norbert Michel has more on this myth in The Dispatch this week.)

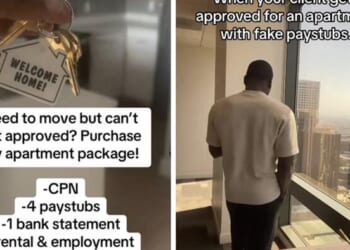

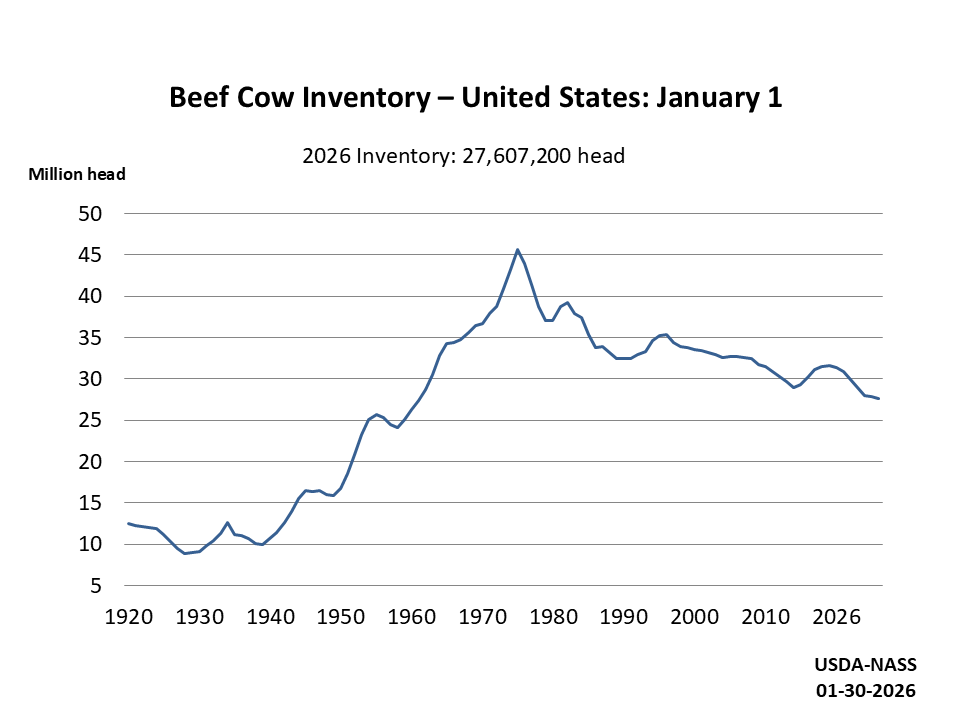

Trump’s populist attack on Big Meat would be similarly ineffective: As Reason’s Jack Nicastro explains, there’s no evidence that meatpackers are, as Trump alleges, “criminally profiting at the expense of the American People,” because the real culprit for high beef prices is the greatly reduced supply of cattle in the United States and from Mexico, which is struggling to stave off the New World screwworm. (More bad news on that front today, unfortunately. Sorry, fellow carnivores.)

Other proposals, meanwhile, would be downright bad for most Americans:

- As Cato’s Nick Anthony explains, interest rate caps would do to consumer credit what price controls always do: create shortages and/or reduce quality. Put simply, rates reflect an issuer’s fixed costs and a borrower’s credit risk, so people deemed “too risky” by credit card companies would simply lose their cards and thus be forced to turn to other, costlier funding sources (or to skip rent or other payments altogether). As Anthony details in The War on Prices, research on payday lending shows how this populist policy works in practice: States that capped loan rates (Illinois, South Dakota, Georgia, Arkansas, North Carolina, etc.) saw declines in both the availability of small-dollar loans and consumers’ overall financial well-being. Other research shows similar effects—including at the federal level (the Military Lending Act of 2007) and internationally—and the industry estimates that around 47 million Americans would suffer if a Trump/Warren rate cap ever took effect.

- Trump’s drug price controls, Cato’s Ryan Bourne documents, could harm patients by curbing firms’ incentives for drug innovation (and thus future output). “Economists Darius Lakdawalla and Dana Goldman,” he notes, “estimate that a 10 per cent drop in [pharmaceutical company] revenues would lead to 2.5 per cent to 15 per cent fewer new drug approvals.” Previous research shows similar effects, which in turn impose major long-term economic costs (via reduced life expectancy and economic growth).

- Leveraging Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, meanwhile, might modestly lower mortgage rates below where they’d be otherwise, but any such reduction would increase housing demand and, without other changes (e.g., on the supply side), thus cause home prices to rise as more homebuyer dollars chase the same number of listings. The plan would also raise serious institutional issues and expose taxpayers to additional risks and costs.

In each of these cases and plenty of others, the reality is that—to the extent there even is a problem that policy can solve—actual solutions are difficult both politically and practically. As we’ve discussed, for example, the bulk of serious housing policy reforms target state and local laws surrounding land use regulations and permitting, with federal policy playing a secondary role. To the extent Uncle Sam can help with home prices, moreover, the policies are often politically unpalatable (e.g., selling off federal lands, eliminating demand-side subsidies, or killing off the GSEs) or require congressional action. And, as Michel notes, politicians’ desire to make homes more affordable often runs headfirst into their desire to portray homes as a surefire way to build wealth.

It’s a tough nut to crack—something Trump himself is now realizing. His January 20 executive order on institutional investors, as Fortune notes, “is relatively toothless: It leaves it to Treasury to determine what counts as a large investor while urging Congress to pass legislation banning such sales.” And just last week he bizarrely promised Americans that he wouldn’t “destroy the value of their homes so somebody who didn’t work very hard can buy a home”—a promise that contradicts his recent efforts to make homes more affordable (i.e., cheaper).

There are similar real-world hurdles for the non-housing proposals. Trump’s interest rate caps, for example, were widely panned and already look dead in the House, where Speaker Mike Johnson dismissed them “as an ‘out of the box’ idea that shouldn’t be taken seriously.” (LOL.) And Bloomberg reported shortly after the Big Meat investigation opened that Trump’s own DOJ had mere weeks earlier “closed a years-long antitrust probe into the meatpacking industry during the Covid-19 pandemic.” Meatpacking companies accused of profiteering, meanwhile, “have been reporting losses as ranchers have kept herds at the smallest in more than half a century as they grapple with high interest rates, expensive feed and droughts.” Greedflation, this is not.

Finally, all these issues—housing, drugs, food, etc.—conflict with Trump’s love of tariffs and protectionism more broadly. The president could, for example, unilaterally lower tariffs on construction materials to make homebuilding a little cheaper, but instead he’s increasing them. He wisely walked back new tariffs on beef and other food imports late last year, but there’s little chance he’ll champion legislation that removes all the other import barriers still in place and/or reforms all the U.S. trade laws clearly biased against imports (including food). Trump could reduce drug prices a bit, Cato’s Michael Cannon explains, but that would require nixing the current prohibition on the reimportation of drugs and medical devices from all developed countries—aka “the trade barrier that enables the very price discrimination that vexes Trump.”

Good luck, as they say, with all that.

As I’ve written repeatedly (and as the Cato Institute will document in a big project this spring), while not every economic problem is fixable by federal policy, there are levers that Washington policymakers could pull to make food, housing, and other necessities a little more affordable today. But these policies are often complicated (read: boring), their effects are often slow and invisible, and—by killing off longstanding political rents and reducing government power—they usually offend a prized political constituency, if not several. In short, there’s nothing “horseshoe” about ’em.

Summing It All Up

None of this is to say that Trump, Bernie, and AOC will lock arms next Labor Day to belt out a few verses of “The Internationale,” and it’s clear that on some economic issues—environmental regulation, AI, wealth and corporate taxes, etc.—the president and lefty politicians remain far apart. Given the limited take-up of the progressive stuff Trump has recently proposed, moreover, it’s not like his big left turn has put the U.S. economy at serious and immediate risk of widespread price controls, crippling taxes, anticorporate crusades, and other populist boondoggles. And, as always, we must remember that the President just … says stuff sometimes (aka all the time).

Nevertheless, the stuff Trump says is important—and depressingly so. As we’ve discussed repeatedly, for example, political capital and policymaking time are finite, so minutes spent debating or trying to implement nonsense proposals to regulate Big Meat (or whatever) are minutes that the government likely can’t spend on more serious policy and advocacy. Furthermore, the president is still the president and remains extremely influential on the right, so his toe-dips into progressive policy are sure to breed copycats among ambitious Republicans looking to distinguish themselves on Capitol Hill or in crowded GOP primaries. His proposals also create a permission structure for more Republican deviations from longstanding party principles. Republicans have unsurprisingly cheered Trump’s groundless populist plans, and others are sure to do the same for anything else he proposes, regardless of whether Bernie or AOC first conceived it.

Trump’s forays into economic leftism also threaten to remove a longstanding political check on leftist policy ambitions. If a progressive becomes president in 2028, for example, Republican attacks on her proposals to regulate interest rates, subsidize homeowners, or attack “corporate greed” will be less effective now that Trump already endorsed some variation thereof. And if a Trumpy president returns to office after that, the interventionist policies might remain in place or even be expanded—just to benefit the Red Team’s favorites instead of those from Team Blue.We’ve already seen this “ratchet effect” in trade policy, with each party’s populists building off the others’ efforts to inject the government ever-deeper into international transactions. The next step will be the national ones.

Chart(s) of the Week