It’s hard to draw a line showing where our new era of political violence began. Was it last summer when President Donald Trump survived a sniper’s bullet by a hair’s breadth only to narrowly avoid a second assassin weeks later? Perhaps the fall 2022 attack on the husband of the then-speaker of the House, or the attempted assassination of a Supreme Court justice just months earlier? The January 6, 2021, assault on the Capitol surely seemed like a sea change.

Well before Wednesday’s shocking assassination of conservative activist Charlie Kirk at a Utah university, there were inflection points. A mass shooting at a congressional baseball practice in 2017 severely injured Republican Rep. Steve Scalise. Then-Democratic Rep. Gabby Giffords of Arizona was shot in the head by a gunman in 2011. Fourteen years later, you can make a grim tally of the violence since using Giffords’ comments. “The murder of Charlie Kirk breaks my heart,” she said in a statement Thursday.

But after the specter of presidential assassination reemerged in Pennsylvania and Florida last summer, the trajectory of political violence has only worsened. The country seems set on a reversion approaching the chaos and disorder that defined decades of the last century. It’s worth reexamining the political attacks of the last year if only to resist the creeping indifference driven by the growing regularity of the violence.

Nearly each of the last 12 months have witnessed politically tinged violence and killings. The attacks vary in severity but reflect a broad array of targets ranging from politicians to business leaders to protesters.

Last September and October, a man repeatedly attacked an office shared by the Democratic National Committee and the Kamala Harris campaign in Tempe, Arizona, firing shots at the office on three separate occasions before authorities apprehended him.

December and the early months of the new year saw an expansion of targets beyond political offices. UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson was murdered in December on a sidewalk in Midtown Manhattan by a gunman who shot him in the back. From January through March, a series of attacks took place on Tesla facilities and vehicles—some Tesla owners reported purchasing anti-Elon Musk bumper stickers as a hedge against vandalism. But party facilities weren’t entirely spared this spring: Arsonists set fire to the New Mexico GOP’s headquarters in Albuquerque.

In April, a man targeted Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shapiro and his family while they were at the governor’s mansion on the first night of Passover. The attacker set fire to the residence and later told authorities he would have attacked Shapiro with a hammer if he had reached him.

In May, a man bombed a fertility clinic in Palm Springs, California, killing himself and injuring four others. Just days later, a shooter murdered a young Jewish couple in Washington, D.C., as they left the Capital Jewish Museum; the pair had worked as aides at the Israeli embassy.

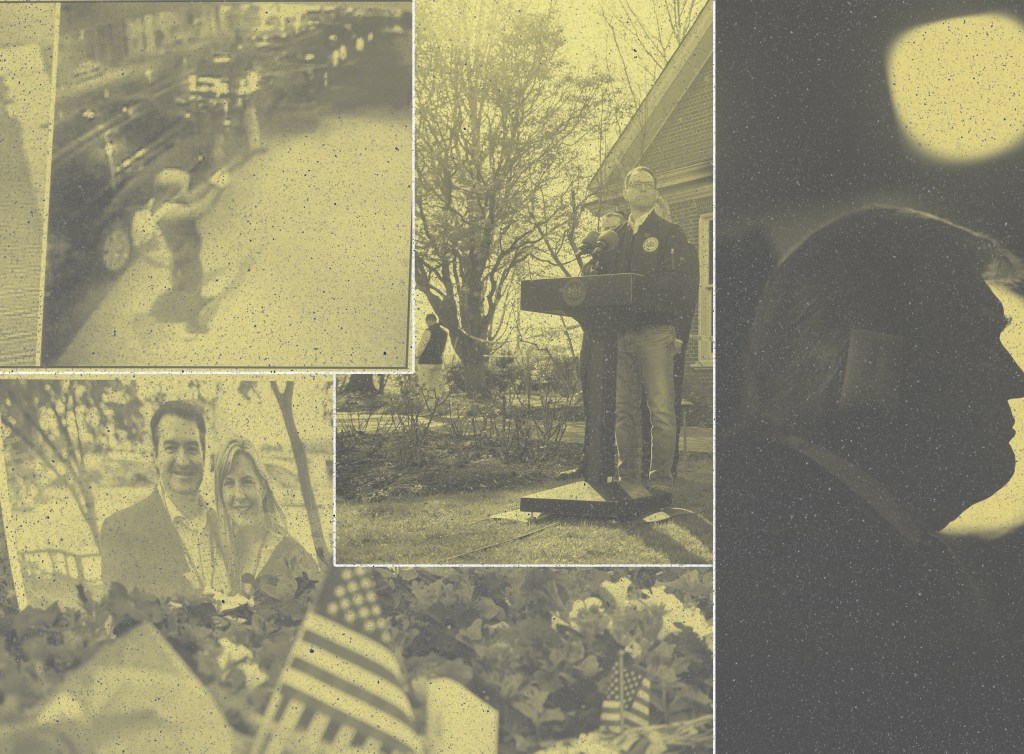

In June, a man firebombed demonstrators marching in Boulder, Colorado, to support Israeli hostages. The attacker threw Molotov cocktails at the crowd, injuring more than a dozen people and killing an 82-year-old woman who died afterward from wounds sustained during the attack. Later in the month, a gunman shot and severely wounded Democratic state Sen. John Hoffman and his wife at their home in the Minneapolis area. He later drove to the nearby home of Democratic state Rep. Melissa Hortman, where he murdered the lawmaker and her husband. The assassin had also tried to target two other state lawmakers’ homes in the same night. The next day, a man attempted to kidnap the Democratic mayor of Memphis, Tennessee, Paul Young, while he was at home with his wife and children.

On July 4, a group of armed assailants attacked an Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detention facility in Alvarado, Texas, in what authorities described as an ambush designed to draw out and kill ICE employees. A police officer responding to the attack was shot in the neck. Three days later, a gunman assaulted a Border Patrol facility in McAllen, Texas, shooting at Border Patrol staff and agents and injuring a responding police officer; the agents eventually killed the shooter. At the end of the month, four people were killed in Midtown Manhattan by a gunman apparently trying to target the National Football League offices; the shooter committed suicide at the scene.

In August, a 30-year-old man attacked the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) headquarters in Atlanta. The shooter fired nearly 500 rounds and killed a police officer before turning his weapon on himself.

The professed motives of the attackers are clearer in some instances than in others, with many citing a mix of personal grievances, political conspiracies, and ideological leanings. All were clearly troubled individuals, with some showing signs of mental instability. In nearly all of these incidents, partisans rush to draw a line of causality from an attack or killing to the rhetoric of a particular political tribe before there are confirmed details about perpetrators’ motives and even after, when the facts confound attempts at political sorting. Some Republican lawmakers quickly blamed the Butler assasination attempt on Democratic rhetoric, but FBI investigators didn’t find any clear partisan motive for the shooter—his internet history in the month before the attempt revealed searches for campaign events for both Trump and then-President Joe Biden.

The impulse to cast blame on a broadly defined political enemy and use the latest atrocity as further evidence of an ongoing civil war only helps reinforce the spiral of radicalization, hatred, and violence.

As others have observed, the growth of political violence is a lot like climate change. Trying to prove climate causality for any single weather event is often a fool’s errand. But climate does have an effect on trendlines. While the public square turns more toxic and digital factories incubate and multiply demonization, the political atmosphere deteriorates.

And the evidence of civic breakdown is mounting. Researchers have documented hundreds of cases of political violence in recent years, a rate nearing the mayhem of the 1960s and ’70s. In 2024, the U.S. Capitol Police investigated nearly 9,500 threats and concerning statements against members of Congress and their staff and families, up from 4,000 in 2017. The U.S. Marshals Service recorded more than 500 threats to federal judges in the 2025 fiscal year.

While observers disagree on whether the current increase in violence is similar to the upheavals of the last century, what’s new is how reactions to political attacks play out online. Virulent celebrations of killers and dehumanization of their victims have filled the corners of social media platforms following each incident. While many public figures have unequivocally condemned the violence, choruses of online celebrations and justifications continue unabated. These twisted reactions reflect only a small portion of active social media users, but the broader consumption of such content further coarsens the public conscience.

One poll last year found that 20 percent of U.S. adults agreed with the statement that Americans have to resort to violence to get the country back on track. The Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, in collaboration with College Pulse, released a national survey of college students this week, finding that 34 percent of students say it’s acceptable to use violence to stop a campus speech, up from 24 percent in 2021.

Kirk’s murder marks a dark turn in the violence. It’s no longer the representatives of political parties or government officials who face elevated risks; it’s public advocates. What began with lawmakers could now include opinion makers. January 6 showcased how violence can reshape politicians’ behavior. As former Sen. Mitt Romney revealed, some of his Republican colleagues apparently decided against voting to impeach or convict Trump after the insurrection for fear of violence against them or their families; threats to personal safety are one factor contributing to the wave of recent congressional retirements. How will the latest violence shape the world of political commentary and advocacy?

The shock of an attempted presidential assassination might have marked a turning point for the better, but the downward spiral has continued. The last year bears out that an increasingly bitter, divided, and angry public goes hand in hand with violence from extremists at the margins of civil society. And if uninterrupted, violence against public figures doesn’t end there.

Take the case of 22-year-old Joshua Kemppainen. After the Butler assassination attempt, the northern Michigan resident vandalized a vehicle and signs bearing pro-Trump messages before using an ATV to run down an 81-year-old man trying to replace some of the damaged signs. The next day, after calling the police to confess to his actions, Kemppainen killed himself with a rifle. The young man’s family members said he suffered from mental illness.

It’s impossible to know what Kemppainen would or wouldn’t have done absent the events at Butler, but it’s also difficult to say his subsequent actions had no catalyst in a political environment featuring growing violence.