What Jim Brown asks of Malcolm X in that scene is a lot like something I sometimes wonder about when it comes to the sort of people who lately have been talking about (if you will indulge the imbecilic neologism) “heritage Americans.” There have always been attempts to sneak ethno-nationalism into those corners of the American way that are creedal and universal. It certainly is not the case that race and ancestry have been anything other than major factors in American life, often destructive factors, and it is impossible to understand the American founding without understanding that it was a project of a philosophy and ideology rooted in the Anglo-Protestant liberal tradition, part of the particular culture of a particular people. There is a reason that until about five minutes ago the broad American elite almost exclusively comprised those described by the acronym WASP—white, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant.

The weird thing about these so-called heritage Americans and the partisans of heritage-Americanism: There are damned few WASPs among them.

I have often teased my old friend Mark Krikorian, arguably our country’s most important advocate of immigration restriction, for his beautifully unassimilated Armenian surname—in fact, he grew up speaking Armenian at home and spent part of his young adulthood studying in what was then Soviet Armenia. Nick Fuentes, the comically effeminate would-be Fuhrer of American neo-Nazism, does not seem to understand that the people whose top issue is “Build the Wall!” are also by and large people who would prefer to see everybody called Fuentes on the south side of said wall. Stephen Miller does not hail from one of those famous Jewish families that sailed over on the Mayflower—his grandfather was born in a shtetl in what is now Belarus. Donald Trump’s grandfather was a draft-dodging German expatriate who set up shop as a part-time flesh merchant—prostitutes and horse meat—in the Yukon before settling in the United States. J.D. Vance thinks that having an ancestor who fought in the Civil War confers some privilege of super-citizenship—just don’t ask these guys which side their people fought on, because Vance apparently does not think that matters. My old National Review colleague Michael Brendan Dougherty no doubt has ancestors who shed blood in the cause of independence … for Ireland, one of several nationalisms dear to his heart. Yoram Hazony is an Israel-born Israeli citizen whose introduction to the rough-and-tumble of this American life was Princeton. I would like to send Nick Fuentes, Yoram Hazony, Pat Buchanan, and Jack Posobiec back in time to explain to George Wallace voters that their spiritual descendants in 2026 are working overtime to make sure that Latinos, Jews, Irish Catholics, and Polish Americans—insert Archie Bunker’s colorful epithets here—can get a fair break.

Not a lot of Dodo Hamilton or Thacher Longstreth types in the ranks of these “heritage Americans.” And that phrase, “heritage Americans”—ye gods: It sounds like they’re talking about tomatoes.

I don’t know that I have a dog in this fight (I literally don’t know: I have no idea what my ethnic background is—the majority view seems to be white, but there are dissenters, and I don’t much care one way or the other) but it does seem kind of weird to me that so many of the “heritage American” dopes and the related anti-immigration crowd are the children of recently immigrated families or from backgrounds that used to be described as “white ethnic,” meaning mostly (but not exclusively) those coming from Catholic and southern or eastern European backgrounds.

In case you are tempted to scold me for lumping serious and decent men such as Hazony and Krikorian in with nut cutlets such as Posobiec—it wasn’t me who lumped them together. It was Hazony et al. Lie down with dogs, get up with fleas.

But, you know: heritage fleas.

Not all of these guys are white supremacists. Some of them are. And they’re out there bumping around listening to Kanye West singing “Heil Hitler.” White supremacy is a primitive philosophy for primitive people but, if only for the sake of tradition, can’t they Make White Supremacy White Again?

Call it a modest proposal.

Economics for English Majors

I recommend reading the remarks of Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney at the World Economic Forum at Davos. Carney is a member of the center-left Liberal Party, but what is probably more relevant to his geopolitical worldview is that he was a banker—CEO (“governor”) of the Bank of England and of the Bank of Canada before that. Because Carney has the temperament of a bank executive rather than the soul of a Winston Churchill or the wit of a Ronald Reagan, this probably is not one of those speeches whose lines are going to be quoted decades hence—there is no Carthago delenda est! in the whole thing. It is not a speech about a day of infamy but years of it. It is worth reading.

For decades, countries like Canada prospered under what we called the rules-based international order. We joined its institutions, we praised its principles, we benefited from its predictability. And because of that, we could pursue values-based foreign policies under its protection.

We knew the story of the international rules-based order was partially false, that the strongest would exempt themselves when convenient, that trade rules were enforced asymmetrically. And we knew that international law applied with varying rigour depending on the identity of the accused or the victim.

This fiction was useful, and American hegemony, in particular, helped provide public goods, open sea lanes, a stable financial system, collective security and support for frameworks for resolving disputes.

… [W]e participated in the rituals, and we largely avoided calling out the gaps between rhetoric and reality.

This bargain no longer works. Let me be direct. We are in the midst of a rupture, not a transition.

Over the past two decades, a series of crises in finance, health, energy and geopolitics have laid bare the risks of extreme global integration. But more recently, great powers have begun using economic integration as weapons, tariffs as leverage, financial infrastructure as coercion, supply chains as vulnerabilities to be exploited.

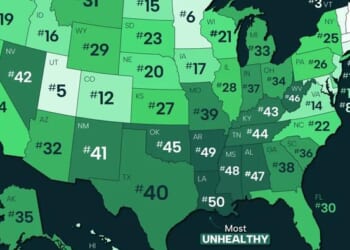

You cannot live within the lie of mutual benefit through integration, when integration becomes the source of your subordination.

The problem for smaller countries and middle powers such as Canada is that they are smaller countries and middle powers: U.S. GDP is about 15 times Canadian GDP, and U.S. GDP per capita, a more meaningful measure of real wealth, is about 60 percent higher than Canada’s. Another way of saying that is that if Canada were a U.S. state, it would not be our poorest state, but it would be near the bottom, in the neighborhood of New Mexico, a lot closer to West Virginia than to Virginia. Americans do not appreciate how radically wealthy our country is. Canada would not be the poorest state, but do you know who would be? Spain. South Korea. Saudi Arabia. Japan.

One could just about imagine an economic bloc based on the mutual interests of the liberal countries that now find themselves the target of American abuse and humiliation. Combine the European Union (GDP roughly $20 trillion), non-EU European economic powers such as the United Kingdom, Norway, and Switzerland (about $4 trillion, $0.6 trillion, and $1 trillion, respectively), Canada ($2.3 trillion) Japan ($4.3 trillion), Australia and New Zealand (about $2 trillion between them), South Korea ($2 trillion), and what do you have? A combined GDP that is only a few trillion more than that of the United States spread over three continents and a very diverse group of countries with economic and geopolitical interests that often are rivalrous and sometimes incompatible. We have seen the limits of international coordination even under such an invasive quasi-state institution as the European Union. EU + Japan + Canada + U.K. + South Korea et al.? One can imagine a coordinating force that could herd those cats in a generally anti-American direction for the sake of counteracting U.S. coercion, and that coordinating force currently is under the management of a man who looks a lot like Winnie the Pooh. It is not for nothing that the unsentimental banker who currently presides over the Canadian government made Xi Jinping his first social call when it became clear that the United States under Donald Trump had become, in effect, a hostile party and a would-be predator willing to consider military force against NATO allies in order to satisfy the neuroses of the doddering game show host Americans have twice dispatched to the White House.

The liberal democracies probably do not have the joint ability to counter American predation in a practical sense, though they have the ability in a hypothetical sense. The power of an ad hoc alliance between the liberal democracies and China against the increasingly hostile and erratic U.S. hegemon is a far less theoretical proposition. Donald Trump is helping to build that alliance every day he serves—as he does, incredibly—as president of these United States.

There are many lessons in there, including lessons for right-wing populists in the United States who thrill to Trump’s abuses and his variegated stupidity. The United States pulled away from the rest of the developed world beginning in the 1990s—and recovered much more quickly from the 2007-08 financial crisis—owing to a relatively small number of technology firms, mainly firms that were started in the 1990s and thereafter (Microsoft, founded in 1975, and Apple, founded in 1976, are the great exceptions), which have provided an enormously disproportionate share of U.S. economic growth, innovation, and dynamism. The Germans would love to have a U.S.-style tech sector, and so would the Swiss and the British and the French and everybody else. What the Europeans lack is not venture capital—it is venture culture. There are plenty of countries with tons of investable capital sitting around on the sidelines, but there aren’t any exciting new technology companies coming out of Saudi Arabia, as much as the Saudi monarchy would love to control and profit from something such as TikTok, a product of Chinese state capitalism.

What our right-wing populists do not seem to quite appreciate is that U.S. economic out-performance is based mainly on technology and technological innovation, even in such old-line industries as oil and gas production. That technological ecosystem is, in turn, based on two things Trump-style populists absolutely loathe—immigration and elite institutions of higher education—and one thing they are starting to learn to hate: finance, especially venture capital but also other forms of private equity investment. The tech economies of Silicon Valley and its outposts in Austin and Boston simply would not exist but for the presence of big, expensive institutions of higher education, both private (Stanford, MIT) and state-run (the University of Texas) and the students they train in engineering, computer science, etc., who are disproportionately immigrants and the children of immigrants. Bringing highly profitable and world-shaping firms such as Google and Netflix out of those academic environments takes a lot of ready money, most of it coming out of the bluest corners of blue states and managed by graduates of Stanford and the Ivy League.

Germans are really good at building cars; rich American immigrants with expensive educations (such as that great Ivy League populist Elon Musk) are good at inventing new kinds of cars and new kinds of car companies. And that is why U.S. GDP per capita is half-again as much as Germany’s. If it is possible to cultivate American-style dynamism in the rich countries of Europe (and Canada and Australia), the needed reforms probably will take a generation or more to take effect.

In the short term, why not ally, if only in a limited way, with China? China desires to oppress Taiwan and its near neighbors, and probably will turn its attention, in the Russian style, to countries with large ethnic Chinese minorities or to Singapore, which has an ethnic Chinese majority. It is likely that Beijing does not see the European Union as a global rival on the level of the United States (because it isn’t) but mainly as a market and a sometimes inconvenient competitor.

The world would be better served by a U.S.-led alliance of liberal democracies against China, but Donald Trump has for now—and maybe forever—taken that possibility off the table. I, for one, am not going to be much inclined to forgive the Americans who voted for that or the supposedly conservative institutions that acted as enablers and apologists.

Words About Words

An ultramontane Catholic is not an ultraconservative, ultra-orthodox, or reactionary Catholic. An ultramontane Catholic is one who emphasizes the pope, the papacy, and papal authority: a Catholic in medieval France or Germany who looks over the mountains—ultra montanus—to Rome for answers, guidance, and authority. The opposite of an ultramontane Catholic is not a liberal Catholic or a moderate Catholic but a cisalpine Catholic, or, in the French case, a Gallican Catholic, one who emphasizes ties to the church in his own community and the authority of his local and national bishops. In our time, an ultramontane Catholic is one who believes whatever it is that Pope Leo XIV believes. The current pope sometimes is described as being conservative as to doctrine but progressive or liberal as to social and political issues. I am not sure that that is exactly how I see him. In a world whose premier institutions are in the main now run by belligerent ass-clowns, a man who is not a belligerent ass-clown looks like Mr. Rogers. That does not make him soft, though some conservative Catholics worry that the pope is less inclined to draw hard lines than they would prefer.

There was a time when ultramontane Catholics were also very conservative Catholics, but, for the past few decades, conservative or reactionary Catholics have been anything but ultramontane, suspicious of the liberalism of Pope Francis and at least a little suspicious that Pope Leo XIV is a squish. There were those who during Francis’ papacy were being anything but rhetorical or facetious when they asked, “Is the pope Catholic?” It was, in some Catholic circles, considered an open question. The Catholic Church is large and diverse and, in spite of the princely character of the papacy, it is not a dictatorship. Just as the president is not the United States, the pope is not the Catholic Church. There are many Catholics of many different persuasions who are happy about what is going on in Rome but despairing of certain practices in their home parishes, and there are some who are perfectly contented with local practice but depressed by the direction of the Vatican. And there are some who are happy with both and some—human beings being beings that are human—unhappy with both, and generally inconsolable.

Because the word orthodox describes both a branch of Christianity and a school of Judaism, describing someone as an orthodox Catholic or an orthodox Presbyterian can be confusing, and there are not very many people outside of Catholic or Presbyterian circles, or Unitarian or Mormon circles, who know what Catholic or Presbyterian orthodoxy is, or what Unitarian or Mormon orthodoxy is.

Orthodox, in the literal sense of the underlying Greek, means straight or correct opinion. The Greek word doxa (δόξα) has more than one sense, one of which is view or opinion, as in orthodoxy or heterodoxy, and another is glory or praise, as in doxology. The Christian doxology (e.g., “Praise God from whom all blessings flow,” etc.) is a liturgical feature borrowed from Jewish practice, with variations on the Kaddish, a hymn of praise, punctuating sections of the liturgy.

The Internet-era verb to dox or to doxx is an abbreviation of dropping documents.

Doxa is related to the Greek word dokein (δοκεῖν) which was George Lynch’s hair-rock band in the 1980s. And in our own time, too I guess—and Lynch still has pretty good hair.

Elsewhere

You can hear me talking politics and despair with Andrew Sullivan here or here, or subscribe and get the whole thing here.

You can buy my most recent book, Big White Ghetto, here.

You can buy my other books here.

You can check out “How the World Works,” a series of interviews on work I’m doing for the Competitive Enterprise Institute, here.

In Closing