Religious violence in Nigeria is not new. It worsened significantly in 2009, when Boko Haram, an Islamist group whose name means “Western education is forbidden,” started its insurgency against the Nigerian government. Since then, both Christians and Muslims who reject the group’s radical view that Western influence amounts to apostasy have faced intense persecution. This has been especially true in the country’s predominantly Muslim north, where Boko Haram is strongest and Christians are a minority. The group gained global notoriety in 2014 after kidnapping 276 schoolgirls—most of them Christian—82 of whom remain missing.

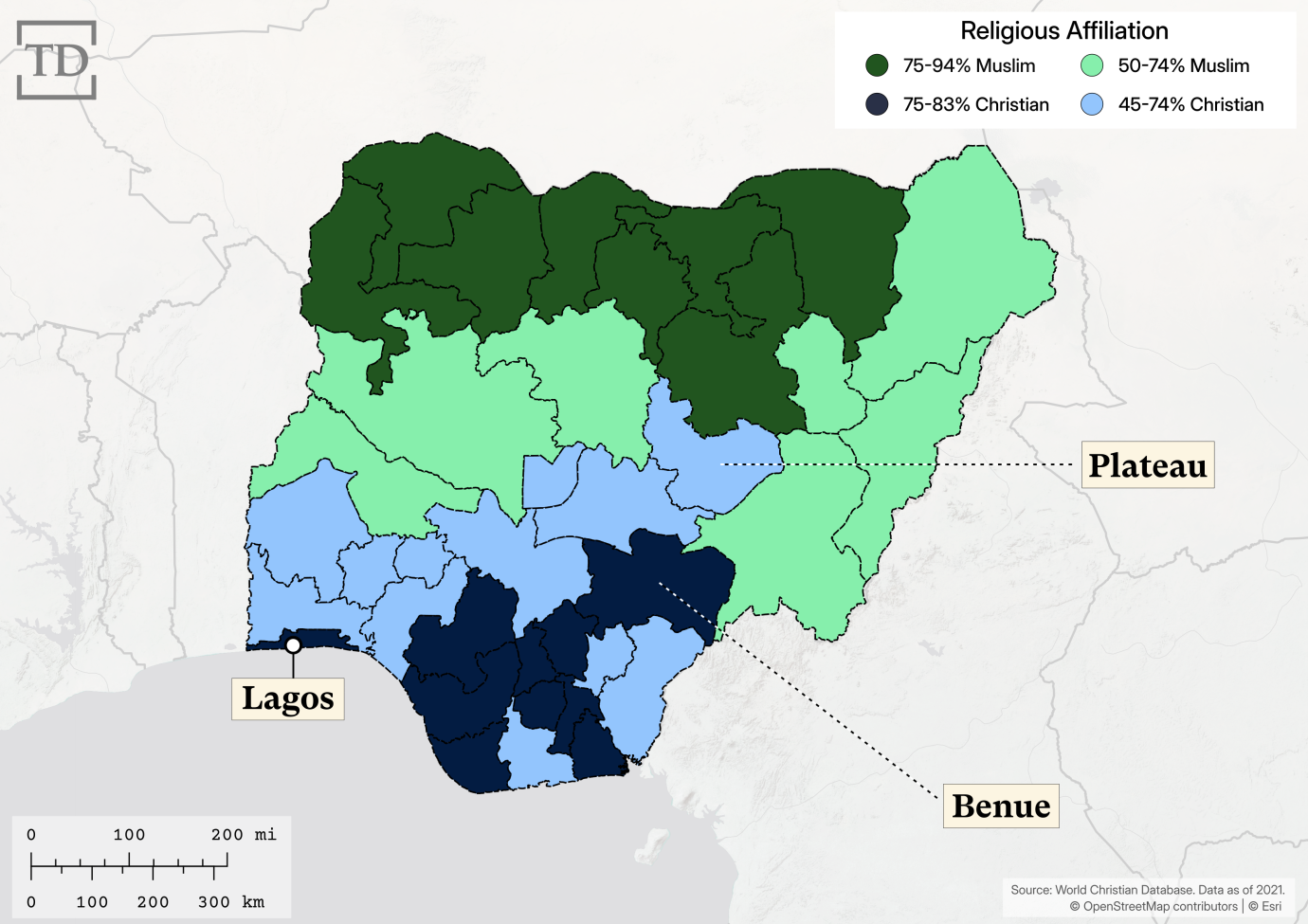

According to Open Doors International, a nondenominational group that supports persecuted Christians, more Christians were murdered for their faith in Nigeria in 2024 than in any other country. While Boko Haram continues its terror campaign in the northeast, it is the surge of religious violence in Nigeria’s predominantly Christian Middle Belt—where the June and Palm Sunday massacres occurred—that has been the source of recent concern for humanitarians, who note that there is increasingly little refuge from Islamist violence in the country.

“It’s the most violent place to live for Christians, hands down,” Brian Orme, CEO of Christian Global Relief, told TMD.

As Boko Haram has recently stepped up its attacks on villages and abducted people for ransom, pressure on Christians is also coming from a separate terror group: radicalized members of the predominantly Muslim Fulani. While Boko Haram’s main goal is to rid the Muslim world of Western influence, the Fulani jihadists are focused mainly on state building, according to Orme. The two terror groups are also ethnically distinct: Boko Haram is mainly Kanuri, a small ethnic group that makes up only 4 percent of the Nigerian population.

“The problem of the Fulanis in Nigeria predates Boko Haram,” Michael Rubin, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute who studies Islamic terrorism, told TMD via email. “The group expands because they see an opportunity to do so.”

Many Fulanis rely on herding cattle for subsistence, and as the northern, more arid part of the country becomes less viable for grazing, they have moved southward, where they have come into conflict with farmers. But according to Orme, who is in frequent contact with local leaders in the region, Fulani herdsmen are increasingly influenced by religion. “There’s a wave of idealism from the Middle East, and it’s impacting the Fulani herdsmen directly, who are already Muslims,” he said. “Many of them are very peaceful, and [herding] is just their way of life, but now they’re under the teaching of radical imams teaching them to take over the land, and it’s building the desire for violence.”

While climate change is a relevant worry in the area, many analysts of the region believe Islamic extremism predates and supersedes those climate concerns, and must be addressed before peaceful Fulani herders and local Christian leaders can have a reasonable discussion over the allocation of scarce resources. “Many people wrongly assume that if you could deal with climate change, then you will have dealt with Islamism,” Ebenezer Obadare, senior fellow for Africa studies at the Council on Foreign Relations, told TMD. “Islamism is a problem. It’s a problem not just for Christians, but also for Muslims who don’t share the core beliefs of Islamists.”

One potential path forward from the strife would be for the government to continue to help the nomadic Fulani adopt modern cattle farming practices, but that likely would not help Christian farmers feel safer in a country where Islamization is spreading. “You don’t solve this problem if you don’t modernize cattle herding in Nigeria,” Obadare said.

As herders move south and Christian communities resist further encroachment, the two sides are increasingly motivated by irreconcilable goals: one seeking to remain in place, the other driven—by both material strain and ideological influence—to expand. “There’s a collision of ideals and of strategy and priorities within both groups,” Orme said. “There’s much better potential to be able to work it out in a peaceful way if we move past the extremist component. That is what’s fueling these tensions and pouring gasoline on the fire, much more so than the nomadic traditions.”