Paid part oAnti-liberalism is anti-Americanism inasmuch as the American project is a liberal project—and an Anglo-Protestant liberal project at that, a fact that my fellow Catholics might meditate on from time to time. American political history has been, in no small part, the story of the development and cultivation of the seed of liberalism that was there from the beginning. Abraham Lincoln, to take an important and obvious example, understood that the case against slavery was right there in the Declaration of Independence and that the continued endurance of slavery was incompatible with the political character of these United States. The American way (as in “truth, justice, and … ”) is a movement in the direction of liberty.

And a movement in the direction of liberty is a movement in the direction of … liberty, including for people who lack refinement or good taste or a decent moral sensibility or a proper religious education. If you have freedom of speech, then you’re going to get both Democracy in America and 50 Shades of Grey, both A Man for All Seasons and Behind the Green Door, both Alexander Hamilton’s The Federalist and Mollie Hemingway’s The Federalist. If you let people vote, sometimes they’ll vote for a sober executive such as Mitch Daniels, and sometimes they’ll vote for an oleaginous troll such as J.D. Vance. Some people prefer California wines to French ones and Red Lobster to Le Bernardin. De gustibus non disputandum est.

The liberation of individuals is to some extent necessarily a matter of atomization, but it is also how new communities are formed, including religious communities. Our world is surely more atomized than the world of my grandfather’s Masonic meetings, just as my grandfather’s world was more atomized than the world that existed before guys like him could get from town to town in a Studebaker, just as the world of my ancestors huddling in half-dugouts on the Llano Estacado was more atomized than the world of a feudal estate. There was surely a powerful sense of community back when our distant antecedents were eating grubs and worshiping the moon and most people died before age 3. Tradeoffs are a thing.

But don’t go poking around in serious Christian thinking for your case against liberalism.

“Immunity from coercion in civil society … means that all men are to be immune from coercion on the part of individuals or of social groups and of any human power, in such wise that no one is to be forced to act in a manner contrary to his own beliefs, whether privately or publicly, whether alone or in association with others,” in the words of Pope Paul VI, not exactly a raving radical or cultural liberationist. Just as freedom is a prerequisite of a freely chosen Christian life, so is freedom a prerequisite for authentic communities of conscience and communities based on interests of other kinds. Free trade and freedom of worship are not the same thing, but they are mixed up with one another in ways that are difficult if not impossible to disaggregate—which would be a foolish thing to do even if you could.

Boutique rightist radicalism can be a lot of fun and sometimes makes for good reading (as in the case of my friend Helen Andrews, about whom you may have read a bit lately, here giving the hairy eyeball to women’s suffrage) but that kind of thing is, politically speaking, fundamentally unserious. Cultural revanchism is generally simpleminded (no less in my case than in others—I do not exempt myself) in that it cannot quite digest the contradictions that define our cultural moment: e.g., young Americans are up to their nostrils in digital pornography which simultaneously makes them miserable and represents a culture of consumer libertarianism that they cannot even conceive of giving up. Simpleminded reaction believes that we can deal with the pornography problem by prohibiting pornography—which, in addition to being technically unfeasible, conflates the observable symptom with the underlying cultural disease. The disease is not liberty or liberalism: Liberalism does not cause bad choices any more than ink causes bad writing. The creation of that which satisfies an appetite, healthy or not, presupposed the existence of the appetite.

(Ink? He really is a reactionary!)

Other than as involves my professional obligations, I do not have much interest in untangling the storks’ nest of anxiety and resentment that is contemporary digital pop culture. Writing in the New York Times, Callie Holtermann claims: “Everyone wants to understand the generation below them.” No, everyone does not. Let’s just say that everyone is a very, very big word, and there are at least a few of us who are not tremendously interested in the insights and sensibilities of the generations that produced the incel and “6/7.” Count me out. The notion that the young necessarily have something to teach the rest of us should have died with Sharon Tate and her friends, whose murder at the hands of the Manson cult was the crowning achievement of American youth counterculture.

But it is worth spending some time really thinking through the reality that right-wing digital counterculture and left-wing digital counterculture are the same damned thing, a gigantic online role-playing game in which the always-online tradwives selling their saccharine pastoralism and the genderfluid Brooklynites with master’s degrees in puppetry need one another as foils, because without that animating competition, the game simply falls apart—it isn’t hide-and-seek if nobody is looking for you.

Both sides of that unitary counterculture are invested in the nonsensical notion that we are at an apocalyptic moment, and that things have never been as bad as they are now. If you believe that horsepucky, go read Frederick Douglass—things have damned well been worse.

So, where does it stand here and now?

We have more young people suffering from digitally induced anxiety but fewer children dying of measles or crippled by polio, at least until that throbbing cretin Robert Kennedy Jr. gets his way. We have a less reverent sabbath but fewer religious wars. More drag queens. Fewer slaves. I can live with that. That’s not a bad tradeoff.

Jennifer Szalai has an interesting essay in the New York Times headlined “Pop Culture Got Stale. Counterculture Went Right-Wing: How the rise and fall of the nihilist hipster gave us the cruel reactionaries of today.” It is a review of Blank Space: A Cultural History of the Twenty-First Century by W. David Marx, author of an interesting book, Status and Culture: How Our Desire for Social Rank Creates Taste, Identity, Art, Fashion, and Constant Change.

An endless stream of content inevitably bumped up against the limits of human attention. Moreover, despite so much frenetic activity, artistic innovation has become scarce. Compared with the burst of modernism of the early 20th century, in which a succession of avant-garde artists set out to push culture forward as a matter of course, the current moment keeps us circling around a whorl of content. Marx suggests that a scarcity of genuine cultural innovation—the “blank space” in his title (which is also the name of a Taylor Swift song)—has left us vulnerable to the fleeting seductions of ephemera and novelty.

… It’s not as if the modernism that Marx wistfully cites provided a “countervailing force” that made the first half of the 20th century any less authoritarian or violent (and some modernists, like Ezra Pound, were thrilled by fascism).

There were many modernists who were thrilled by fascism—and Ezra Pound, an energetic servant of Benito Mussolini’s regime, was more than thrilled. But it seems to me much more to the point that the fascists were thrilled by modernism.

Italian fascism has its roots in a modernist art-school tendency, Futurism, and the fascist aesthetic was to a great extent a modernist aesthetic. Go have a look at photographer Alfred Stieglitz’s heroic, under-construction cityscapes from the late 1920s or Lewis Hines’s man-and-machine photographs of the 1930s, such as the famous “Powerhouse Mechanic Working on a Steam Pump,” which could have been a poster for fascism. Stieglitz (the husband of Georgia O’Keeffe) associated with socialist activists and ideas but would more precisely be described as a romantic anticapitalist—an orientation not alien to fascism. Hine was a New Dealer and a WPA photographer, and, if you happen to be very, very interested in the intersection between New Deal thinking and the thinking of “that admirable Italian gentleman,” as Franklin Roosevelt described Mussolini, then you are reading the right publication but the wrong byline.

Before the war, fascism was intellectually trendy in many progressive circles—there was a good deal of Thomas Friedman’s “China for a day” wishful thinking among the leading intellectuals of the time. You will find a familiar tone in Pound’s naïve economic writing: “I take it [Mussolini’s agriculture minister Edmondo] Rossoni gets more done than all the rest of us economists because he does not allow himself to be too far distracted from the particular and material realities of his grain, his wool, his ersatz wool made out of cow’s milk,” leaving “the state able to use these materials as it needs them.” The most important theme shared between fascism and modernism was rationalism, in both the common sense of the word and in the creedal sense described by Michael Oakeshott in Rationalism in Politics.

That rationalism had aesthetic implications, too, which you can see in everything from the Streamline Moderne designs of the 1930s to Ayn Rand’s detestation of architectural ornament. In at least some of their respective strains, fascism and modernism shared many aesthetic touchstones: the cult of the machine and the cult of the engineer, admiration if not worship of force and action, a pervading sense of hardness. That is not characteristic of every modernist, of course: T.S. Eliot was a kind of arm’s-length pastoralist who disliked the ugliness of industrial capitalism and what he considered its intrusions on tradition and Christian civilization. And the totalitarians were a pick-and-choose bunch, too: Adolf Hitler was in many ways a modernist in architecture and political thinking, but he campaigned against “degenerate” art and literature, meaning modernist art and literature, and his taste in personal residential architecture was more high-bourgeois than the kind of monumental thing he put Albert Speer to work on.

That should not surprise us too very much. Aesthetically as well as politically, fascism was, or could be, simultaneously retrospective (which is to say, nostalgic) and future-oriented, for example in the “stripped classicism” in architecture that combined Greco-Roman forms with harder, more modernist, more austere, “rational” lines. The Italian fascists looked back to Roman virtue and forward to modern industrial management techniques—with a sensibility that at times bordered on sci-fi. There are many points of intersection in all that: The Italian Futurists were absolutely in love with aviation, and there was something heroic about the heavens-conquering pilot in the years before air travel sank into Greyhound bus banality—on top of that, there are few endeavors as corporatist in their economic character than commercial aviation, a highly structured partnership between private firms, unions, and government agencies. Aviation was a part of a picture of what the fascists aspired to. Mussolini himself was a trained pilot and wanted Italian aviation to be a symbol of national power: Consider the 1933 Decennial Air Cruise from Italy to the Century of Progress International Exposition in Chicago.

We have a tendency to assume that the things we like are incompatible with the things we don’t like—or even that they are necessarily diametrically opposed. In this case it is modernism and fascism; but that stuff is deep in our political discourse, for instance in the mistaken belief that fascism and communism were diametrically opposed rival ideologies rather than, as Jonah Goldberg argues, variations on a theme.

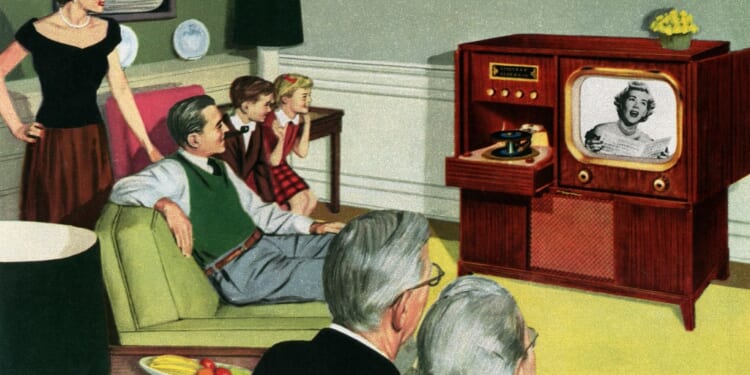

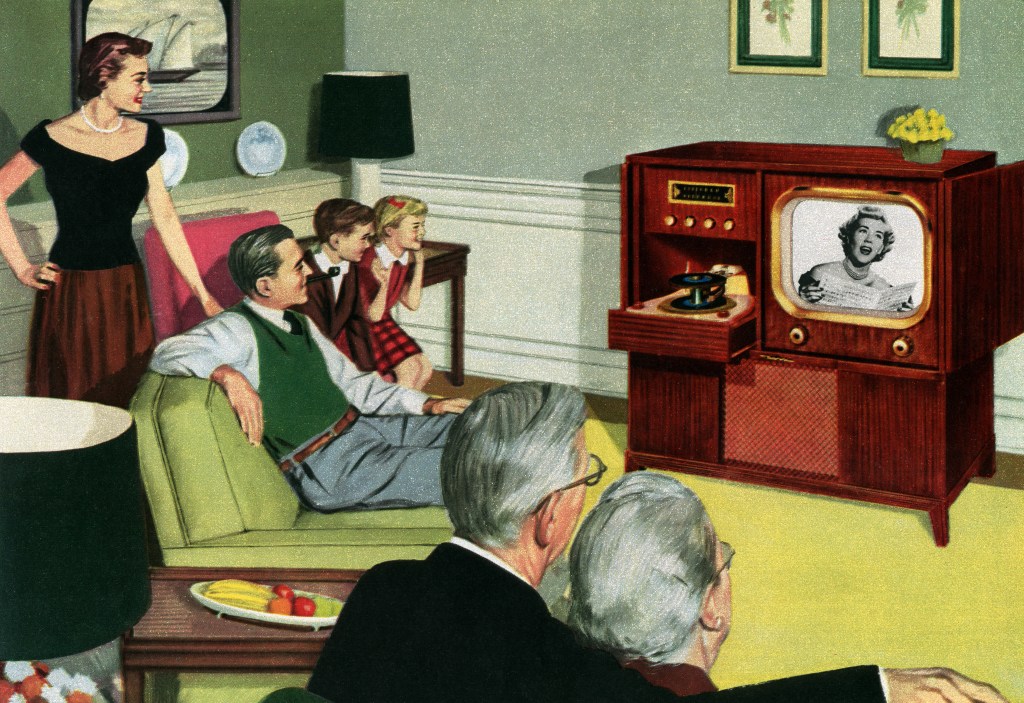

Aesthetics does not tell you everything about a movement or a moment. But it tells you something: A midcentury modernist house in Southern California with a 1957 Bel-Air under the carport tells you a great deal about what the American people were up to in the Eisenhower years. (And I like it!) Without stepping on Jonah’s beat too hard, the streamlined, machine-oriented, and grandiose aesthetics of the late 1920s and 1930s were typical of people who were modernists in art and of people and states that included both European fascists and American progressives. What they shared was not a desire to repress or a lust for power or antisemitism or disappointment with democracy (though these things were all present in varying degrees) but rationalism combined with an optimistic sense that the rationalist professions—the engineers, the economic planners, the scientists and experts—could build better societies the way state-corporate partnerships had built the railroads. The fascists loved locomotives, and progressives still love trains, a rationalist love so irrational that they’ll spend billions of dollars to build an entirely useless “high-speed” (kinda, sorta) rail link between … Merced and Bakersfield, more or less the equivalent of establishing Concorde supersonic jet service between Lubbock and Amarillo.

Why do central planners prefer trains to cars? Because you tell a car where to go, but a train tells you where to go.

And Furthermore …

David Kaufman, formerly my editor over at the New York Post, has started a Substack. Kaufman brings an interesting perspective to his work on Middle Eastern and Jewish issues: that of a black, Jewish, gay, conservative Zionist. He is a bit of a bomb-thrower at times, too, so expect a Substack that is at times angry and profane—I cannot reproduce his headline about Hasan Piker here—but interesting. A piece that also ran in the Telegraph argues that the case for Palestinian statehood is what you get when you apply DEI to diplomacy.

The truth is, while there may be little logic for progressive support for Hamas, the ideology behind statehood is something we’ve all seen before. In fact—across America’s corporations and campuses—we see it all the time: in the obsession with identity and representation; the reliance on coercion and bullying; and in the unyielding focus on equality of outcomes and achievements.

Far removed from any real achievement—and armed with last week’s facade of officialdom—Palestinian statehood is now emerging as the global equivalent of diplomatic DEI (Diversity, Equity & Inclusion).

The playbook is clear. Take legitimate grievances—historic inequality in the US, geopolitical displacement over in the Levant—and weaponise them into movements powered by vast funding and abstract demands for power rebalancing and institutional change. Operating under dubious leadership, with scant accountability or oversight, DEI and Palestinian statehood privilege optics over accomplishment, representation and ritualisation ahead of historical fact.

This is why Spanish, Irish and Norwegian recognition was so important to the statehood crowd last week; much like the DEI metrics used to measure minority advancement, the goal here is quantifiable milestones.

And Furtherermore …

In the week’s least-surprising news: Pro-Putin creep was on Putin payroll. From the New York Times:

A former politician in Nigel Farage’s Reform U.K. party was sentenced on Friday to 10 and a half years in prison for taking bribes to make pro-Russia statements in the European Parliament.

Nathan Gill, 52, admitted to being paid between 2018 and 2020 to make speeches and media appearances that were scripted by Oleg Voloshyn, a Ukrainian politician who had been an official in the Kremlin-backed government of Viktor Yanukovych. Mr. Voloshyn was a member of a pro-Russian political party at the time of the offenses.

From British “nationalists” to American right-wing influencers—Dave Rubin, Benny Johnson, etc.—you are seldom more than a hop, skip, and a jump away from a nice big pile of rubles.

Economics for English Majors

What’s a bubble? The cynic will answer: It’s a bull market you ain’t in. But if you are a stock investor who recently has enjoyed appreciable returns, you’re in the AI market, bubble or no.

The question being debated right now is whether we’re talking about tulips or railroads here. You all know the story of the tulip mania of the 17th century—there was a craze for tulips that drove the price of bulbs up so much that people got into the market as a purely speculative enterprise, which increased demand further, hence driving up prices, hence inviting more speculators into the market, in a vicious circle until somebody discovered that the actual consumer demand for tulips was wildly out of proportion to investments in tulips. Tulips do not have much of a shelf life. But railroads do. In the 19th century, there was a tulip-ish mania for railroad stocks and a vast over-investment in rail—but railroads last a long time, and the United States reaped real economic benefits from all that rail investment even though some investors took it in the shorts.

AI optimists such as Bill Gates think this is more of a railroad moment than a tulip moment. And that is because the AI bubble (if it is a bubble—it isn’t one until it pops) is not only a matter of share-price speculation: What’s driving the AI economy right now is infrastructure development, all those data centers and power projects (including, one hopes, new nuclear facilities) meant to serve them. Unlike many of the companies that make up the Hall of Shame of the 1990s dot-com bubble, many of these AI firms have real revenue, real profits, and real products that create real value. Nvidia isn’t Pets.com.

The thing is: Optimists such as Gates et al. may be right that the current AI boom is more like an infrastructure buildout than share-price speculation, but that does not mean that its effects—including on share prices and on the individual and institutional investors holding those shares—does not have the potential to produce destructive chaos. And destructive chaos in the markets invites even more destructive overreaction from Washington. It does not take a sci-fi imagination to picture a Democratic-run Congress blaming the AI bubble—you can hear the denunciations of “corporate greed” already!—as a pretext for bailing out public-employee pension funds that have been mismanaged for decades.

Money is fungible, but not all money is the same: An investment return you are counting on this year is very different from one you are counting on in 20 years. There are many infamous money-losing investments (such as Milken-era “junk bonds”) that turned out to be pretty darned good investments for those who had the wherewithal to ride out the volatility and not sell at the worst time. As a good financial adviser will tell you, you don’t have to be super-rich to be the kind of investor who can endure that kind of downturn—but you do need to be diversified. Go back and read the Wall Street Journal’s excellent reporting in the wake of the subprime-mortgage meltdown, and you’ll be treated to stories about people with household incomes of $80,000 who had $2 million in mortgage debt on five different properties on the theory that houses are safe … as houses. Back in the 1990s, you had people of modest means losing their butts on derivatives investments they did not understand because somebody’s brother-in-law told them that derivatives were a can’t-lose deal offering outsized returns. (Some brothers-in-law are better about money than others—I happen to have one of the smart ones, no doubt wandering around some very scenic ski slopes this week.) I’m a 53-year-old man with four children ages 3, 1, 1, and 1, so I figure I’m working until 80 or so no matter what. Your life plans may be different—but if your economic plans can be wrecked by a single reversal in a single investment sub-sector, you’re probably not doing it right.

But even if you are doing it right, Washington has a way of making Wall Street’s problems everybody’s problem. The guy who is on his way to becoming a trillionaire today may very well be up for a taxpayer-funded bailout tomorrow. That’s the dumb world we live in.

Words About Words

An article in Salon describes Shawn McCreesh of the New York Times as a “former assistant to Maureen Dowd and the ‘lead writer’ for Donald Trump’s 2024 campaign.” To my ear, that sounds like McCreesh was, as the sentence says, a “writer for Donald Trump’s 2024 campaign,” i.e., an operative of the Trump campaign. He was not. He was a New York Times feature writer covering the campaign. It is a sloppy sentence that gives the wrong impression.

The cable channel formerly known as MSNBC is now MS NOW. Doesn’t MS NOW sound to you like a double-barreled blast of 1970s feminism? Ms., the crackpot magazine, and NOW, the crackpot activist organization? On-brand for the folks over at the former MSNBC, I guess.

Elsewhere

You can watch me talking about … everything … with Jon Ralson and John Podhoretz at IndyFest in Las Vegas here, if you are inclined.

You can buy my most recent book, Big White Ghetto, here.

You can buy my other books here.

You can check out “How the World Works,” a series of interviews on work I’m doing for the Competitive Enterprise Institute, here.

In Closing

Some people have written in to suggest that Marjorie Taylor Greene has taken my three words of advice: “Resign. Resign. Resign.” I will note that my full advice was that she resign her seat and return to private life for a period of penance, work, and contemplation. Maybe she is doing that. More likely, she is running for governor of Georgia. Time will tell.