The trouble here likely prompted a few Democratic senators to cross the aisle to vote in favor of progressing a government funding bill on Sunday evening. But even if the government reopens within the next few days, restoring the system to full strength will take time—and long-running issues with the design of America’s air travel agencies and infrastructure mean capacity issues at American airports are likely here to stay.

The primary reason for the reduction in flights is safety concerns. Air traffic controllers aren’t being paid during the shutdown. If they do show up to work, they have found that many of their colleagues didn’t, leaving the crucial position understaffed. Duffy told CNN that on Saturday at Atlanta’s Hartsfield-Jackson airport—consistently ranked the busiest airport in the world—18 of 22 air traffic controllers failed to arrive for work. On Saturday, at that airport alone, 370 flights were canceled, and 683 were delayed.

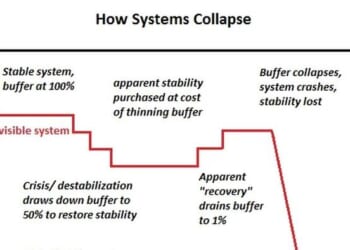

When flights at one airport are canceled, the “national airspace system is subject to cascading or ripple-type effects,” Philip Mann, a professor at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University and a 17-year veteran of the FAA, told TMD. The FAA tries to plan for known disruptions, but a government shutdown is far too broad and significant to balance against.

Multiple aviation experts who spoke to TMD also noted that while worries about flight disruptions are very much warranted, travelers should not be concerned about flight safety. “It makes total sense what’s being done from a safety perspective,” Shawn Pruchnicki, a professor at Ohio State University and the former Air Line Pilots Association chief accident investigator, told TMD. “We have all worked very hard, all of us in the industry, to achieve a significant margin of safety” for events like the shutdown, he said. A reduction in flights, he argued, meant that federal regulators were preserving a balance between the number of planes in the air and the number of air traffic personnel directing them.

Mann also noted that the FAA’s safety mission takes priority over its other mandate, to ensure efficient travel. Air travel remains “super, super, super, safe,” he said. For all the pain flight reductions are causing, the government maintains that the changes are simply the FAA following its mandate, rather than an attempt to inflict political punishment. “This is not political. This is strictly safety,” said Duffy on Sunday.

The transportation secretary also told reporters that even if congressional leaders reach a deal to end the shutdown, the effects of the disruption would linger. Before the shutdown, roughly four air traffic controllers retired per day, Duffy said. “I’m now up to 15 to 20 a day are retiring, so it’s going to be harder for me to come back after the shutdown and have more controllers controlling the airspace. So this is going to live on in air travel well beyond the time frame that this government opens back up.”

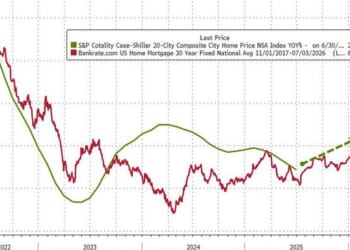

Structural issues at the FAA that predate the shutdown will make Duffy’s task in leading the air travel system back to full capacity even harder. The first is its funding source. Congress funds the FAA through annual appropriations, primarily based on airline ticket taxes, Robert Poole, the director of transportation policy at the Reason Foundation, told TMD. The U.S. is “a very big outlier” compared to other countries, he said, in its reliance on what is “not a very robust or reliable revenue stream.”

Most other countries fund air traffic control systems and other infrastructure by charging the users of airspace and airport services. Nav Canada—a privately run non-profit organization established by the Canadian parliament in 1996—owns and operates the country’s air navigation system. It sets the rates paid by airlines and other users for the use of airspace and other infrastructure, and receives no government operating subsidies. But it must reinvest any profits into reducing fees or improving services, and must keep fees tied to the direct cost of service provision.

By contrast, as it’s not a separate entity from the government, the FAA is unable to issue its own bonds to fund long-term investments in its operating infrastructure. With legislators scrutinizing its budget every year and often reluctant to provide the long-term financing needed for systemic upgrades, many U.S. airports are left with a patchwork of safety and operations systems, many of which are so old that replacement parts for them no longer exist.

And, there has been a shortage of trained air traffic professionals for decades. Government officials estimate that the U.S.’s air travel system needs 14,600 trained controllers to operate, but as of earlier this year, only 10,800 were working, often on punishingly long shifts. More than 90 percent of U.S. airport towers are understaffed, according to a 2023 report.

There’s also only one facility in the U.S. solely dedicated to training their replacements: the FAA’s academy in Oklahoma City. A proposal in Congress last year to build a second facility to expand the controller pipeline (through a training process that takes years) died due to opposition from Oklahoma’s delegation. However, in October 2024, the FAA signed agreements with Tulsa Community College and the University of Oklahoma to provide the same curriculum and training in a college setting, and seven other colleges and universities have signed up since.

As the country nears the busiest travel days of the year, an official end to the shutdown will still leave the FAA with a mammoth task on its hands.

“It’s going to take us days to assess the controllers coming back into their facilities or their towers,” Duffy said on Friday. After that, airlines will need to rebook the planes they grounded, and flight schedules will need to be rebooted and reorganized. “It can be days, if not a week, before we get back to full-force flights when the shutdown ends,” said Duffy.