Data centers are getting blamed for America’s rising carbon emissions. I mean, of course they are. Old-school, anti-growth environmentalists seem willing to toss any criticism possible at the warehouse-sized supercomputers. They use too much power! They use too much water! They generate too much pollution!

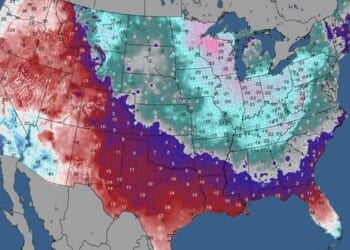

The charge is wildly overblown. Yes, US greenhouse-gas emissions climbed an estimated 2.4 percent in 2025, reversing two years of decline. But a new analysis from the Rhodium Group points to a familiar culprit: cold weather. Emissions from buildings jumped 6.8 percent as furnaces ran harder, while higher natural-gas prices pushed utilities to burn more coal, lifting coal generation 13 percent and power-sector emissions 3.8 percent.

Data centers did play a role, but a limited one. Rhodium finds that electricity use rose fastest in commercial buildings, up 2.4 percent, with data centers, crypto mining, and other large users adding to demand, especially in Texas, the Mid-Atlantic, and the Ohio Valley. That extra load mattered at the margin. What drove emissions higher, though, was how the grid met that demand—leaning on coal and gas—not the servers themselves.

The distinction matters because electricity demand is not emissions. What turns higher load into higher carbon is the fuel mix that meets it—a “you go to war with the army you have” problem. In 2025, the grid leaned what was available. Cold snaps and commodity-price swings did the rest. Data centers acted as an accelerant, not the spark.

What we’re talking about here, then, is a policy failure, not a technological one. And the scale of what’s coming makes the clean-energy question unavoidable. Goldman Sachs estimates global data-center power demand will rise more than 160 percent by 2030 compared with 2023, as AI workloads expand and efficiency gains—doing more computing per kilowatt-hour—likely slow. If fossil fuels meet roughly 60 percent of that incremental demand, global emissions could climb by 215–220 million metric tons, about 0.6 percent of world energy emissions.

But those numbers describe a scenario, not a fate. In the short run, demand shocks get met by whatever fossil capacity is lying around. In the medium run, sustained demand from customers with strong balance sheets is precisely what makes new power generation financeable.

Big Tech is already moving fast. Example: Meta just announced deals with three nuclear providers—Vistra, TerraPower, and Oklo—to eventually power its Prometheus supercluster in Ohio, projects the company says will add 6.6 gigawatts by 2035. The arrangements span life extensions at existing plants and investments in next-generation reactors still under development. Meta isn’t alone: Amazon and Google have signed similar pledges. Through long-term contracts, the hyperscalers are positioning themselves as anchor customers for clean power rather than passive grid users.

(Important point: Goldman says nuclear can’t do the job alone. Wind and solar, paired with battery storage, could supply up to about 80 percent of a data center’s power needs going forward, though intermittency means some always-on generation is still required. Natural gas is likely to remain a short-term bridging fuel.)

And for what it’s worth, a new Heatmap survey of 55 climate insiders found roughly two-thirds don’t believe AI and data centers are significantly slowing decarbonization. As University of Chicago economist Michael Greenstone put it, every use of electricity—air conditioning, lighting, industrial motors—”slows decarbonization” if clean supply fails to keep pace.

It’s best to think about the 2025 emissions bump as a warning about that infrastructure, not about AI power needs. It also suggests how emissions outcomes could improve if grids are allowed—and encouraged—to build the clean energy future America needs.

The post AI’s Carbon Problem Is Really a Grid Problem appeared first on American Enterprise Institute – AEI.