Authored by Gene Pisasale, via RealClearWire,

“… a thirst for absolute power is the natural disease of monarchy …. To the evil of monarchy we have added hereditary succession … the first is a degradation and lessening of ourselves … the second, claimed as a matter of right, is an insult and an imposition on posterity.”

– Thomas Paine, “Common Sense”

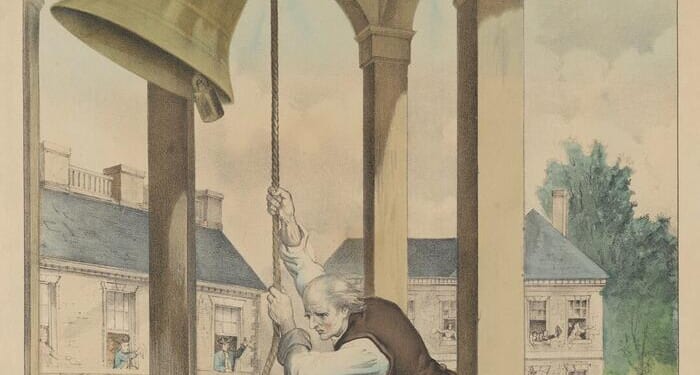

On Jan. 10, 1776, Robert Bell did something that could have landed him in prison for treason against King George III of England.

In his small shop on Third Street in downtown Philadelphia, Bell printed an incendiary 47-page pamphlet, published anonymously, calling for rebellion against the Crown and independence from Great Britain.

Its author was a little-known Englishman who had befriended Benjamin Franklin in London two years earlier.

Franklin was impressed with the man and recommended that he emigrate to the colonies, which he did that same year.

Arriving in America just five months before shots were fired at Lexington and Concord, Thomas Paine had a front row seat as the American Revolutionary War was unfolding.

Despite “the shot heard ’round the world” on April 19, 1775, calls for independence were relatively muted throughout the colonies, historians estimating that only about 25 percent of citizens supported the move.

That changed after “Common Sense” hit the streets, being widely read and discussed openly in taverns and coffeehouses throughout the land.

Within approximately one year, an estimated 100,000 copies were sold—a remarkable feat considering the population of America was only about 2.5 million.

After its widespread distribution, Paine’s words proved highly persuasive to tens of thousands across the colonies, nudging support for independence to well over 50 percent. Paine followed it up with an even more persuasive clarion call—“The American Crisis”—in December 1776, its words so grippingly effective that General George Washington had it read out loud to his troops in an attempt to keep his Army together:

“THESE are the times that try men’s souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands by it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph.”

An Incredibly Risky Wager

As America had a miniscule Army and ineffective Navy in 1776—versus Great Britain with the most powerful Army in the western hemisphere and a colossally-equipped Navy, only the most aggressive wagerer would have made the bet that the colonies could prevail.

After the move for independence was put into writing on July 4, 1776, the die was cast.

The members of the Second Continental Congress understood that what they were hoping to achieve would be a “long shot” by any reasonable standard.

Early Losses, but Some Victories

King George III and his senior military officers had a lot to be optimistic about early on. The city of Boston was surrounded, then Crown forces took control of another major port—New York—and Washington’s troops were not only on the run—they were ragged, nearly starving, and dangerously low on supplies.

Retreating across the Delaware River to Pennsylvania, Washington knew he had to be bold to survive. With the help of financier Robert Morris and others, Washington received enough cash and materials to forge not only one, but two attacks that would change the way people viewed the war.

The Battle of Trenton on Dec. 26, 1776 and the Battle of Princeton on Jan. 3, 1777 were brilliantly conceived and stunningly successful victories at a time when the Commander knew his Army was near collapse. Being a deeply religious man who often visited local churches during the war, Washington was convinced that a “higher power” had kept his dream—what he called “the Cause”—alive.

A Leap in the Dark

Historian John Ferling captured the essence of this tumultuous era effectively in “A Leap in the Dark: The Struggle to Create the American Republic.” In the book, Ferling describes the “behind the scenes” workings of all the major players, noting their strengths, their weaknesses, and their own doubts about whether they could possibly succeed.

That Washington’s Army was desperate for a victory to end the conflict is an understatement.

Most days they were just hoping to find food and stay on their feet. Though the Continental Army had eked out a few wins, the odds still favored the British. The war would drag on until British General Cornwallis found himself in deep trouble in Virginia, getting surrounded by Washington’s as well as France’s troops and warships leading up to the climactic Battle of Yorktown in October 1781.

A World-Changing Event

Though it may be apocryphal, when Cornwallis surrendered, it has been reported that the British troops were so stunned, they played the English ballad “The World Turned Upside Down” as they relinquished the battlefield to Washington—who literally “by the grace of God” had managed to survive.

The soldiers who had stood by Washington from the beginning, through the defeats in New York and Philadelphia, the horrendous freezing Winters at Valley Forge and Morristown, surely felt in their veins what those assembled in downtown Philadelphia had written on July 4th: “… with a firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor.”

Considering the overwhelming odds against us, it is not a stretch to say that the words to the tune written decades later were true: “America! America! God shed His grace on thee …”

Looking back 250 years, it becomes clear that the sacred fire of liberty which burned in those hearty souls was not only a flame that couldn’t be extinguished—it was an idea which was destined to change the world.

Loading recommendations…