On August 11, a Chinese coast guard ship collided with a Chinese naval destroyer as both were aggressively pursuing a small Philippine coast guard vessel near Scarborough Shoal in the South China Sea. Within minutes, thanks to an embedded reporter and the Philippines’ assertive transparency policy, astonishing early videos of the incident began circulating around Manila and beyond.

For Beijing and the Chinese Communist Party this was a tactical setback and a major embarrassment, but that’s not the lesson we should take away. The bigger story of the South China Sea is that China is rapidly consolidating its gains in what is this century’s most successful expansionist campaign.

As I recently testified before the Senate, the U.S. is decades into losing a gray-zone war and is still without anything even remotely resembling a coherent counterstrategy, even as its treaty ally the Philippines has seen its internationally recognized maritime rights and entitlements devoured by Chinese aggression.

China attempted to make up for its embarrassment by immediately blaming the Philippines and even absurdly suggesting it may be owed compensation for a mishap that the world clearly saw in near-real time. Four awkward days passed before Beijing admitted fault. Of course, this blame-shifting was typical CCP propagandistic gaslighting. The Middle Kingdom owns this disaster lock, stock and barrel, and not merely for conducting a highly dangerous and poorly coordinated pursuit.

What really matters, however, is why a 7,500-ton guided missile destroyer was present in the first place; why it joined in running down (and nearly ramming) an ally’s lightly armed 320-ton coast guard vessel; and why America has done so little in response to this latest outrage at a key maritime feature that China is 13 years into progressively stealing.

Scarborough Shoal was once a vitally important traditional fishing ground for generations of Filipino communities, though China and Taiwan also claim the atoll. That began to change in 2012, when a standoff between the Philippines and China—coupled with some ineffective diplomatic interventions by the U.S.—ended with the Philippines withdrawing. But China has dramatically accelerated its aggression over the past 18 months, blocking all Philippine traffic from the shoal by its enforcement of a 30-nautical-mile exclusion zone.

These actions are clearly illegal under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), to which both the Philippines and China are signatories, as well a 2016 arbitration case won by the Philippines, which China refuses to recognize:

“[T]he Tribunal finds that China has, through the operation of its official vessels at Scarborough Shoal from May 2012 onwards, unlawfully prevented Filipino fishermen from engaging in traditional fishing at Scarborough Shoal.”

Leading up to the August collision, the Philippine Coast Guard’s BRP Suluan had managed to slip past China’s thick screen of paramilitary exclusion-zone enforcers. Such an affront apparently could not be tolerated, prompting the destroyer—which under normal practice would simply lurk menacingly on the horizon—to intervene with catastrophic results.

This, however, is an aberration from the recent norm. In fact, what makes China’s Scarborough campaign particularly instructive is how it has until now demonstrated Beijing’s evolution from the crude military confrontations of the 1970s and 1980s to today’s sophisticated gray zone operations.

While China’s efforts to control the South China Sea date back to the 1970s, it was America’s 1992 withdrawal from its Philippine military bases and post-Cold War “peace dividend” signaling that really enabled China to broaden its maritime expansion project. This campaign has over 50 years systematically seized and consolidated control over vast areas of the South China Sea through sustained paramilitary pressure, calculated escalation, unscrupulous lawfare, and constant political influence operations. The conquest of Scarborough Shoal is merely its most recent success.

China’s opportunistic gray-zone template was epitomized by its gradual conquest of Mischief Reef, a ring-shaped coral atoll—fully submerged at high tide—in the middle of the Philippines’ exclusive economic zone. China first established “fishermen’s shelters” at the reef in 1994, buttoday the atoll is one of seven massive artificial bases in the Spratly Islands—and one of three equipped with military-grade runways and harbors.

Critically for China’s lawfare narrative, its outpost established the reef as an “inhabited” feature prior to a formal 2002 agreement with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations that proscribed inhabiting new South China Sea features.

Of course, this same agreement also prohibits the “threat or use of force” in resolving disputes, requires respect for the freedom of navigation, and invokes UNCLOS as binding on all parties. None of that keeps Beijing from holding itself up as the agreement’s most devoted adherent at the same time its application of such technicalities to its own actions is shamelessly flexibile.

That’s because Beijing’s expansionist goals require routine gaslighting with an absurdly tortured presentation of both the facts and the law.

China’s 2013-15 island-building campaign provided another opportunity for the U.S. and its allies to blow the whistle on its gray-zone maritime expansionism, but once again we offered little more than finger-wagging. (I remember this depressingly well, as I was posted to the U.S. Embassy in Vietnam at the time.) President Obama did manage to elicit a Rose Garden pledge from Xi Jinping not to militarize his new artificial islands, but within less than a year the emptiness of that promise had become clear for all to see.

These bases provided the infrastructure that now enables China’s rapidly growing coast guard and militia fleets to sustain operations 800 or more nautical miles from its coast. They serve as the power projection hubs that anchor Beijing’s area-denial operations throughout the Spratly archipelago, supporting recent aggressions like the swarming of Whitsun Reef, quarantine of the Philippine outpost at Second Thomas Shoal, the 2024 takeover of Sabina Shoal, and the constant harassment of energy exploration activities throughout maritime East Asia.

China’s gray-zone tactics extend far beyond the South China Sea. In the East China Sea, Chinese coast guard ships regularly probe Japanese administrative control around the Senkaku Islands, while in the Yellow Sea it recently alarmed South Korea by establishing a remarkably large aquaculture project in contested waters, violating the terms of a 2001 bilateral agreement.

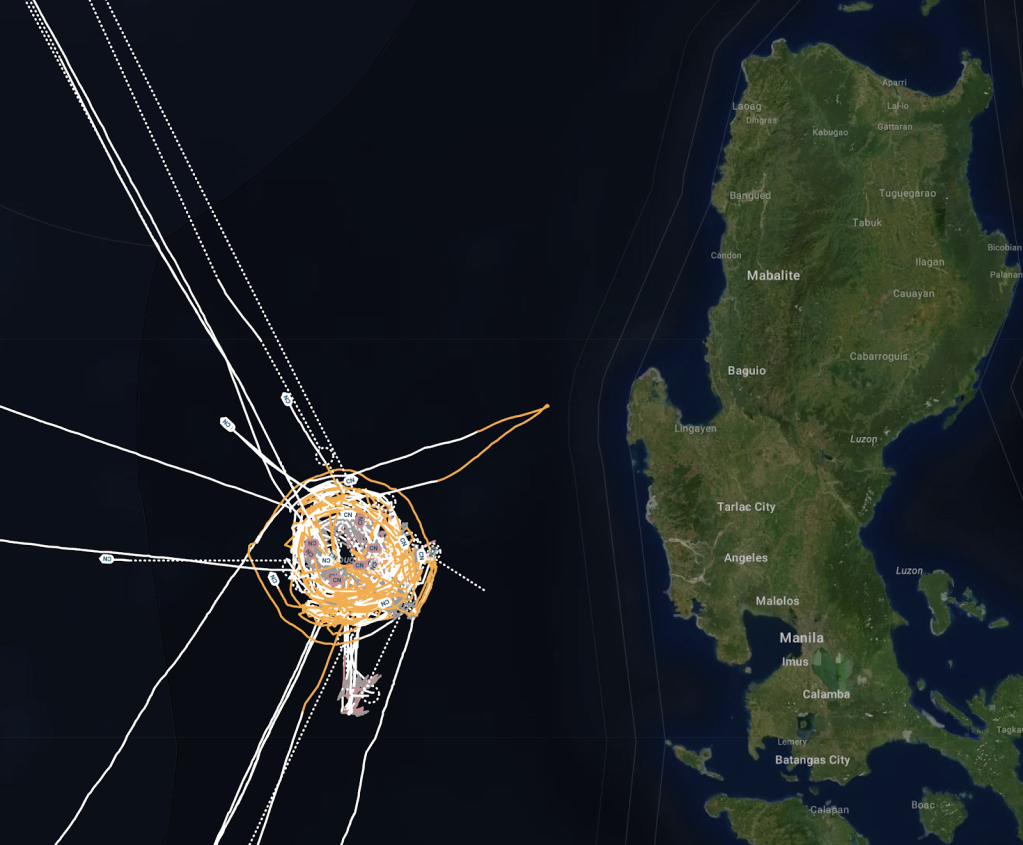

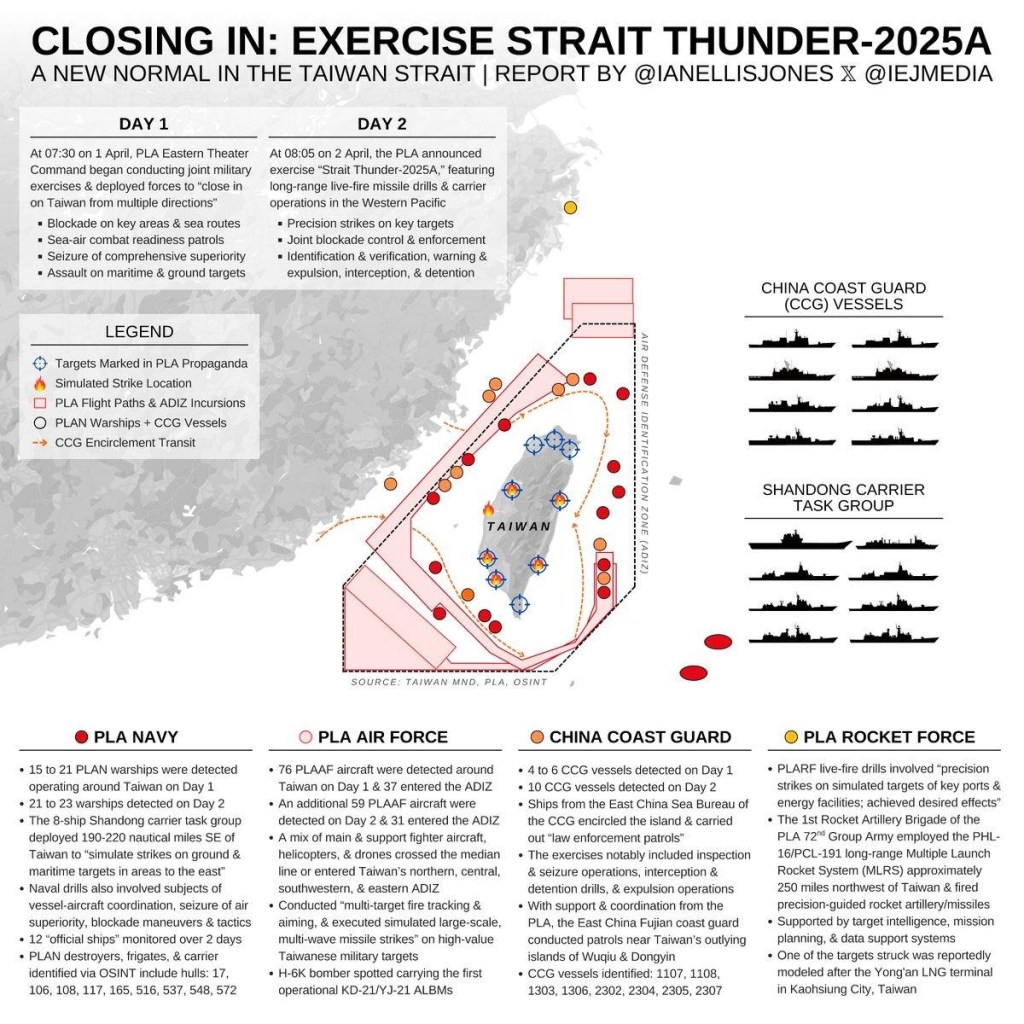

China has also been rapidly intensifying its gray-zone campaign against Taiwan. This includes coercive military activities like the record numbers of military aircraft violating Taiwan’s airspace and joint exercises that menacingly surround the island—including one a year ago in which Beijing released an image of a heart-shaped patrol around the island. (I swear I’m not making this up.)

This happens in conjunction with the sabotage of Taiwanese undersea cables; oil and gas extraction around Taiwan’s Pratas Island; systematic election interference and economic coercion and, of course, nonstop political warfare.

The CCP’s highly sophisticated political warfare machine is a central element in its campaign of gray zone expansion. Designed to shape narratives and undermine resistance, this dimension of China’s strategy may be its most insidious in that it operates largely out of public view. Through a multifront cognitive assault on its rivals and critics (including me) it seeks to muddy the waters around its aggressions just enough to keep them from organizing any kind of serious counter-campaign.

So far it’s been working just fine on its most serious rival, which continues to plan (as we should) for the worst-case scenario of a potential war with China.

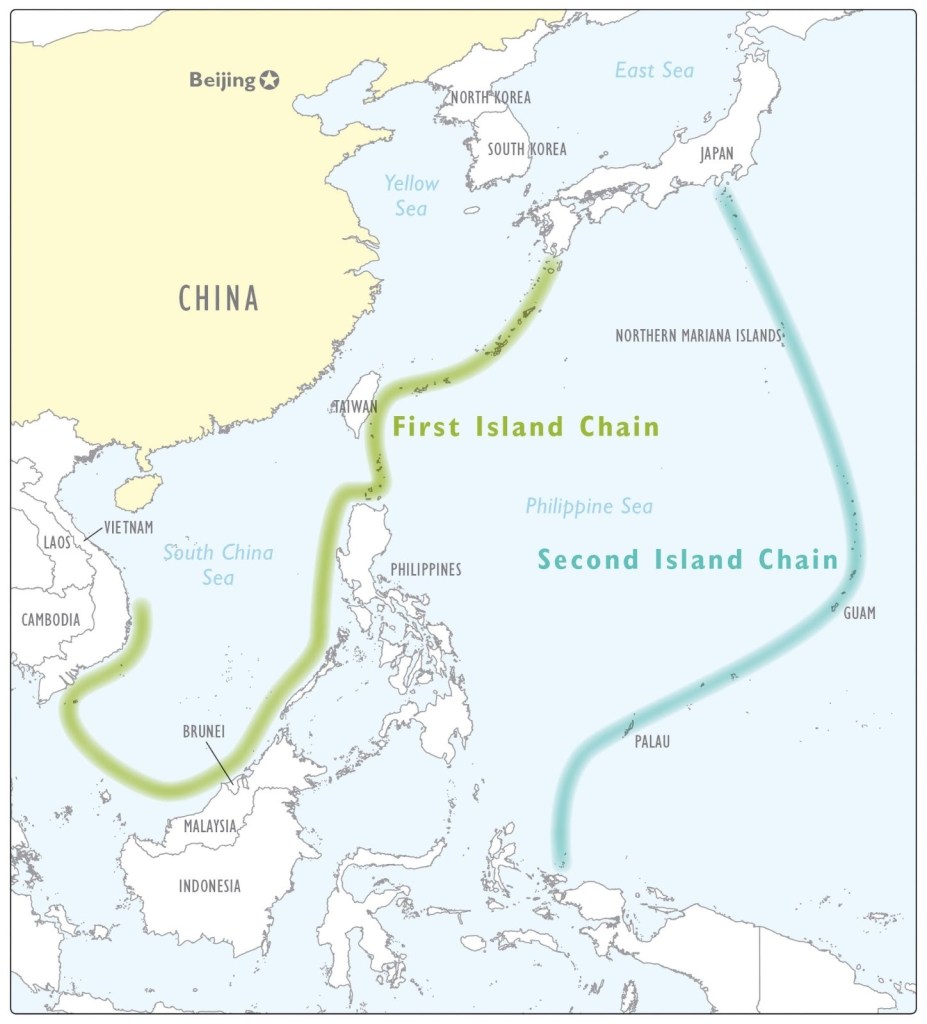

But China does not want to fight a war. No, China believes it can conquer Taiwan, control the South China Sea, bring our East Asian allies to heel and eventually push the U.S. completely out of the first island chain without firing another shot.

America’s continued inability to develop anything approaching a counter-gray-zone strategy is exactly why China employs it. The CCP has figured out that we really like our neat categories and rules-based order: We are either at peace or at war; an action is either legal or illegal; an asset is either military or civilian; a fact is either true or false; crises are to be avoided and de-escalated, not used as opportunities to reset the board in our favor.

China’s gray-zone strategy is designed to exploit the myriad gaps and seams that define our conventional and ordered policy frameworks and deterrence models.

So which agency’s mission is it to counter a vast and growing paramilitary force and political warfare campaign that continues to push south and east from China’s coast to harass and coerce our allies? The answer, of course, is that it’s nobody’s job.

We don’t have a Department of Gray Zone War.

Implementing a national counter-gray-zone strategy will require a single, accountable lead to integrate policy, intelligence, lawfare, messaging, and partner operations—the kind of cross-domain synchronization our adversaries exploit when no one is clearly in charge. Here’s a place to start: designate a deputy national security adviser for gray zone competition with tasking authority, and establish standing interagency cells to synchronize military, diplomatic, law‑enforcement, economic and information tools.

This needs to happen now.

China has mastered the art of (to paraphrase its legendary strategist Sun Tzu) “winning without fighting.” Its approach is built on the belief that its expansionist objectives can be achieved through sustained pressure, legal manipulation, and psychological operations without triggering the alliance commitments and escalation dynamics that conventional military action would provoke.

In fact, during the past three years of Chinese paramilitary escalation with the Philippines, one of the questions I have been asked repeatedly in interviews has been, “Does this incident trigger the Mutual Defense Treaty with the U.S.?”

In other words, does being rammed by a larger coast guard ship qualify as an “armed attack”? What about when a high-pressure water cannon breaks the windows on your civilian fisheries enforcement vessel? Or when “law enforcement” involves surrounding and brandishing clubs and bladed weapons against your outnumbered troops directly next to your military outpost?

The answer, of course, is that nobody really wants to answer that question. China has figured out that while we debate terms and issue strongly worded statements, it can just keep normalizing new aggressions and changing the facts on the water in ways that directly threaten our vital interests in East Asia. It’s a campaign that has been picking up steam for five decades, and it’s accelerating right now.

We desperately need a strategy and someone to execute it. We can’t turn this game around if we’re not even on the field.