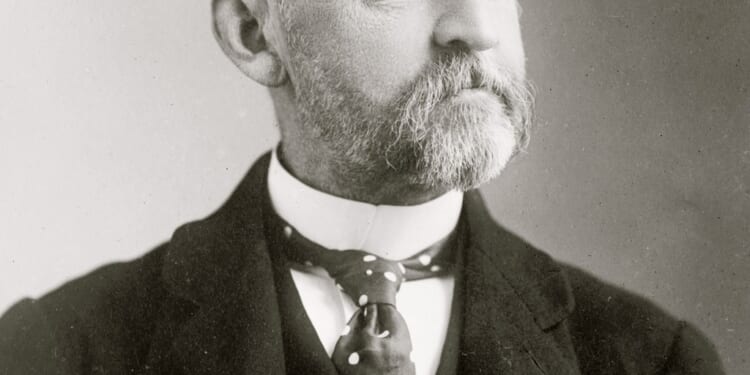

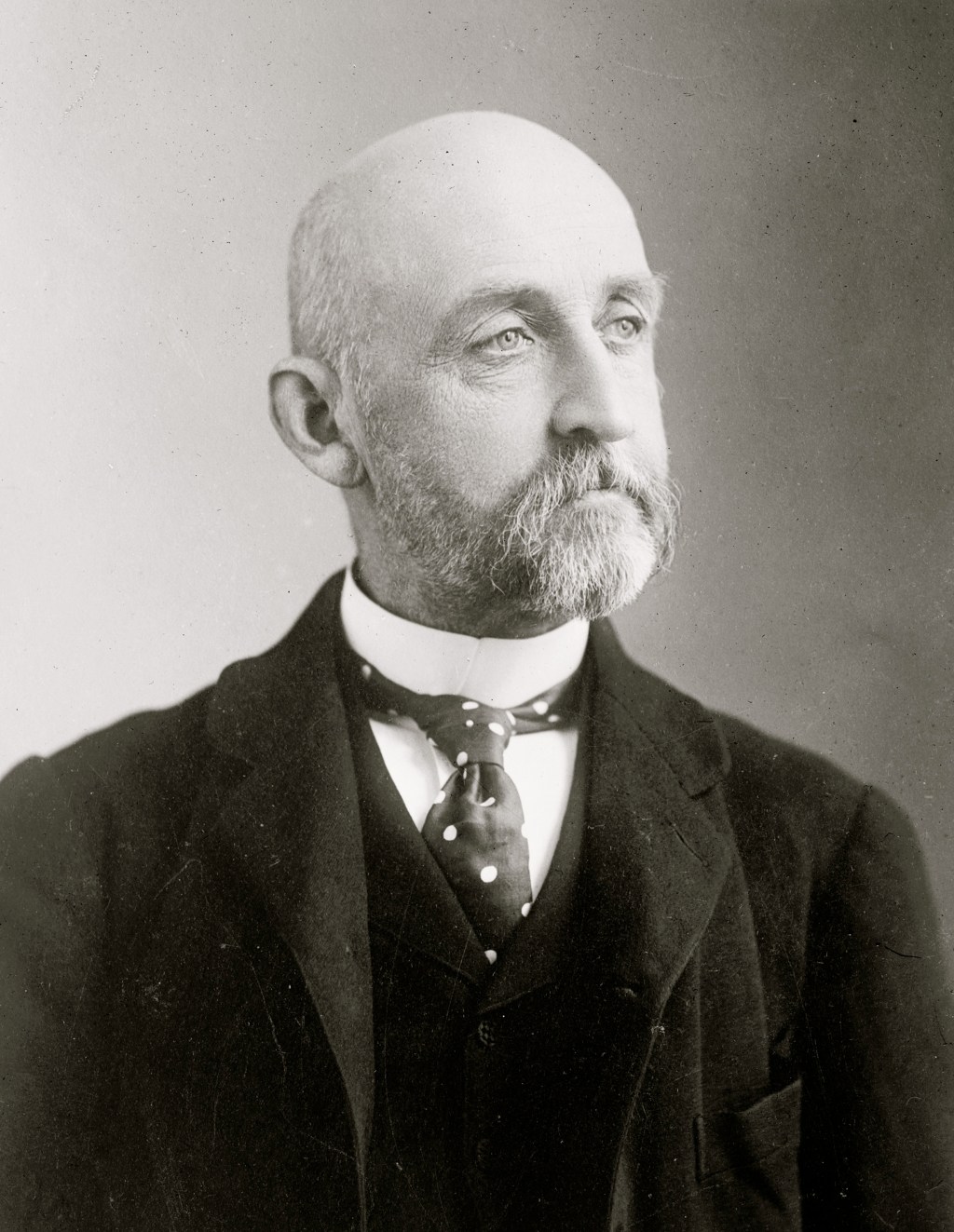

“Indications are not wanting of an approaching change in the thoughts and policy of Americans as to their relations with the world outside their own borders.” Those words could be pulled from a slew of today’s headlines, but they are actually more than a century old. As we hear many calls today for Americans to reimagine foreign relations by retrenching—focusing on domestic issues and giving primacy to our own hemisphere—it’s worth revisiting the words of naval historian Alfred Thayer Mahan. His 1890 essay, “America Looking Outward,” came at a time when America was already focused internally. Mahan had long called for an American view of the world that would require a radical break from its history. While the United States had long been aloof from Europe and uninterested in overseas expansion, Mahan correctly foresaw that those days were ending and that America should prepare to take its place on the world stage.

Mahan is remembered today as an apostle for sea power, and he was certainly that. His voluminous publications on the effective use of navies made him one of the most famous intellectuals of his time. By the time of his death in 1914, Mahan was indelibly associated with the word “sea power.” But he was as much an apostle for sea commerce as he was an advocate for a mighty navy, and he wanted his country to construct fleets sufficient to safeguard a thriving commercial trade that he believed was absolutely essential in the emerging modern world. As historian Nicholas Lambert wrote in his recent work on Mahan’s life and thought, Mahan was an able scholar of “the symbiotic relationship between trade, wealth, and power.” Mahan foresaw a world in which the United States vigorously engaged in global trade on the seas that he regarded as a global commons, with naval power to protect global American shipping. He was, in short, the first American globalist.

Mahan, ironically enough, grew up in the shadow of West Point, the son of distinguished Army professor Dennis Hart Mahan. While he bucked his father in choosing the navy as a career—the elder Mahan believed his son lacked the temperament for any military career at all, in fact—Mahan owed much to spending his formative years in an environment that stressed academic rigor and deep thought about military affairs.

Graduating from the Naval Academy in 1859, Mahan entered the service just in time for the greatest war the nation had known to that point. He spent the Civil War serving honorably but unremarkably, mostly on blockade duty. He followed up the war with a cruise to Asia and then spent time in Europe. His initial fame came not at sea but in the classroom. He was tapped in 1885 to give lectures at the newly created Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island, and his lectures there eventually became the book for which he is known today, The Influence of Sea Power Upon History. It was indeed primarily about the importance of naval power, though he also began this volume by immediately pointing out the “profound influence of sea commerce upon the wealth and strength of countries.”

“If Americans hoped that they could greatly increase their participation in overseas markets while maintaining an aloof posture from the rest of the world, they were sorely mistaken.”

John Doe

One reason for Mahan’s heavy emphasis on the importance of naval power is that he wrote at a time when his country essentially had none. The United States had built a navy worthy of a great power for the Civil War, then promptly dismantled it as soon as the fighting ended. Sooner, actually: Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles began selling off ships before Robert E. Lee surrendered. Blockading the entire Confederate coastline and providing naval support to coastal and riverine operations demanded massive resources, and at the height of the war the U.S. had hundreds of ships in commission. But once the shooting stopped, American interest in the sea dropped off dramatically. The country was weighed down by twin goals of Reconstruction in the ruined South and massive expansion across the West, and few saw a need for a powerful fleet. America’s first admiral, David Dixon Porter, bemoaned that the Navy had been eliminated altogether, with only slight exaggeration.

Few Americans in 1865 cared. The truth was that American naval history had been one of strict limits on ships, ambitions, and especially budgets. Before the Civil War, the United States had counted on coastal fortifications and a relatively small Navy that could protect American trade and show the flag, but was consistently dwarfed by the British Royal Navy. Americans took great pride in naval successes in the War of 1812, and the Navy was engaged in overseas exploration and, dramatically, in forcing Japan open for trade in 1853. These were exceptions, though. After 1815, American naval policy was dominated by “antinavalists” who built defensive naval forces and avoided global entanglements. In wartime, America counted on its ships and a swarm of privateers to inflict economic pain on the enemy and relied on coastal fortifications backed by a limited Navy to safeguard American shores.

In the aftermath of the Civil War, Americans reverted to form. The massive Navy that had blockaded the Confederacy was replaced by a maritime force more in line with America’s historic views of sea power. Rather than powerful battleships, the Navy of the Gilded Age built cruisers that were intended to attack enemy shipping if war ever came. The United States thus stood idly by in the late 19th century while European nations made impressive leaps in battleship design and firepower. America, as Secretary of the Navy Benjamin Franklin Tracy put it, built railroads while other countries built navies, and thus the country fell dangerously behind when it came to sea power.

Mahan saw this state of affairs as potentially disastrous. If America lacked the capacity to project power abroad, it started any dispute with any other nation at a stark disadvantage. Americans looking to the Navy as a purely defensive force that could safeguard coastlines and unleash cruisers on enemy commerce were deluded. Scattershot attacks on commercial shipping had proved an annoyance to the British in the Revolutionary War and War of 1812, but they had not and could not achieve decisive effects. It was Britain’s powerful fleets that shut down the American economy through brutally effective blockades that achieved meaningful effects on the outcome of both wars. In the Revolution, timely French aid saved the United States. The War of 1812 was different, however. In his 1905 book Sea Power in its Relations to the War of 1812, Mahan argued that Britain got the better of its former colonies at sea, with potentially disastrous results. The weak American Navy could capture a few British frigates and win some public relations victories, but it could not save the country from a stifling blockade nor prevent Britain from landing a sufficient force ashore to burn down the American capital.

The Influence of Sea Power Upon History was Mahan’s first—and most famous— work, but his later writing offers up his more mature and nuanced thought. Influence captures the major idea that permeated his career, though: States that cultivate adequate sea power have enormous advantages over their competitors. States that possess sea power can deter wars, and they are far better equipped to win wars they are forced to fight. But crucially, states that invest in sea power are able, in war and peace, to enjoy flourishing economies based on unfettered access to global trade. This fixation on seaborne commerce runs through all of Mahan’s writing. Trade was at the heart of questions of war and peace. He wrote, “Commerce “on the one hand deters from war, on the other hand it engenders conflict, fostering ambitions and strifes which tend towards armed conflict.” Naval power could not exist in a vacuum, functioning purely as a defensive mechanism to be activated in the event of war, because “in practice the political, commercial, and military needs are so intertwined that their mutual interaction constitutes one problem.”

Mahan in his wildest dreams likely never foresaw the level of American hegemony exercised in the aftermath of the Cold War, but he certainly would have approved.”

John Doe

Mahan did not believe battle fleets could win wars by challenging one another, as his views are too often crudely characterized. Control of the seas was only a prerequisite to the real way an enemy had to be brought to its knees—economic strangulation. The side that developed its naval resources would likely have to destroy or neutralize the enemy’s fleets as a prerequisite for claiming sea control, but once that control was obtained, it was free to target the real basis of flourishing or catastrophe: seaborne trade. With control of the seas, a nation could blockade its enemy, as Britain had done in the War of 1812 and the Union had in the Civil War, and unleash wholesale warfare against enemy shipping.

Mahan’s thinking not only inspired his argument for fleets that could challenge any enemy in a potential war, but it also led him to advocate for overseas expansion. He was an early proponent of annexing Hawaii, and he argued vigorously for a canal through Central America. Some of his thinking has aged poorly; he was heavily influenced by ideas of Social Darwinism, and he was a man of his time in many of his racial attitudes. These traits were tempered by his devout Christianity and deep sense of morality. There are also indications he envisioned a future consortium of nations, led by the United States and Britain, that would collectively safeguard freedom of the seas, drawn together by a shared certainty that, in military historian Jon Sumida’s words, “general peace founded upon the workings of an international system of free trade” would be a boon to “all major maritime powers,” and America in particular.

Mahan rose to prominence at a propitious time, when the country was ready to hear his message about the need for a powerful Navy to defend overseas commerce. And as Mahan himself perfectly understood, the reasons for building up the Navy had far more to do with economics than national security. For starters, westward migration and settlement ceased to be a major feature of American life. The final clash between the U.S. Army and Native Americans took place at Wounded Knee in 1890. Even this could hardly be called a battle, since the Indians had already been fully disarmed. The West had been won, and in 1893 historian Frederick Jackson Turner famously announced that the era of the frontier was over. Reconstruction had likewise come to a sharp end in the late 1870s, when war-weary Northerners left newly freed slaves at the mercy of their former masters and washed their hands of efforts to transform the South.

Mahan’s writing coincided with other major developments that left Americans more inclined to think globally. European duties had caused a collapse in the price of wheat, devastating Midwestern farmers. Overseas expansion into new markets, particularly the Caribbean and Asia, offered a way out of economic challenges. In short, changing internal dynamics and a realization of the potential of a more global economy pointed Americans toward the views that Mahan advocated.

If Americans hoped that they could greatly increase their participation in overseas markets while maintaining an aloof posture from the rest of the world, they were sorely mistaken. “We also shall be entangled in the affairs of the great family of nations, and shall have to accept the attendant burdens,” Mahan prophesied, and among those attendant burdens was “developing our navy upon lines and proportions adequate to the work it may be called upon to do.”

In time, the Navy developed in the waning days of the 19th century did fuel an American rise to great power status. The fleet of battleships built at the end of the 19th century helped crush the Spanish Navy at the Battle of Manila Bay, and the Spanish-American War marked the birth of the United States’ overseas empire. Theodore Roosevelt, a great fan of Mahan’s work, culminated his presidency by sending a fleet of battleships on an around-the-world tour to announce America’s arrival as a world power.

As for Mahan, he did not live long enough to see the global conflagration of World War I play out. He died in December 1914, while the war in Europe was still building toward its bloodiest days and the American public was firmly committed to staying out of the fight. Yet his theories of naval warfare remained central to American thinking about sea power for generations after his death. Often misinterpreted and misunderstood, he nonetheless remains a major voice in American naval thinking, and recent scholarship has greatly enhanced our understanding of his thought.

But an evaluation of Mahan’s legacy that focuses solely on naval warfare misses the most crucial parts of his thinking. America became—in his lifetime and afterward—remarkably like the country that Mahan envisioned. Battleship fleets protected overseas commerce that covered the globe and made the United States a major player in Asia and the Pacific. Mahan in his wildest dreams likely never foresaw the level of American hegemony exercised in the aftermath of the Cold War, but he certainly would have approved. He remains more relevant than ever now, though. In the essay “The United States Looking Outward,” Mahan noted conditions that demanded his country take global events seriously, and among his concerns was an “ominous … restlessness in the world at large.” He warned that the United States would be foolish to think it could shield itself from global turmoil at the time. The nation heeded his words then. It should keep doing so today.