The most recent jobs report—based on September’s data and released late last month—showed a gain of 119,000 nonfarm jobs for that month but also revised down August’s numbers to a loss of 4,000 jobs.

Data from payroll processor ADP released last week showed a net loss of 32,000 jobs in November. Small businesses accounted for 120,000 lost positions, which was partially offset by gains at larger firms.

A federal report on job openings from October showed no increase in the number of new positions posted.

Taken together, these reports indicate that the labor market isn’t strong, but it isn’t disastrous either.

“There does seem to be some incremental softening in the labor market,” David Wilcox, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics and the director of economic research for Bloomberg Economics, told TMD. “We have no indication that any of that is abrupt or indicative of the kind of dynamics that set in when a recession is on the near horizon. But nonetheless, the trend is not in the right direction.”

The expectation on Wall Street is that enough members of the Fed will be concerned about this trend to call for a rate cut—a small quarter-percentage-point rate cut to 3.50-3.75 percent, from the current rate of 3.75-4.00 percent, if markets are to be believed.

David Beckworth, a senior research fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University and the director of its monetary policy program, told TMD that even though the job market has not “fallen off a cliff by any means, typically with monetary policy, you want to make a decision in a forward-looking sense. You don’t wait to go over the cliff.”

Inflation.

But lowering interest rates means cheaper borrowing and more spending, and inflation—while substantially lower than its recent peak in 2022—is still above the Fed’s 2 percent target. The personal consumption expenditures price index, which excludes volatile food and energy prices from the “basket” of goods and services that it measures, rose 2.8 percent year-over-year in September. And Americans generally do not feel optimistic about the economy.

The University of Michigan’s monthly consumer survey, which tracks consumer sentiment across a broad range of measures such as perceptions of the business climate and personal finances, found that respondents remained far less optimistic than last year. “The overall tenor of views is broadly somber, as consumers continue to cite the burden of high prices,” survey director Joanne Hsu wrote.

Trump’s policies.

Last week, President Donald Trump called Democratic rhetoric about affordability a “con job” and a “scam.” But his tariffs—which have raised the average applied U.S. tariff rate from 2.5 percent to roughly 18 percent, the highest level in nearly a century—have also contributed to price pressures, with The Tax Foundation estimating that the tariffs amount to an average tax increase of roughly $1,200 per household in 2025.

And voters seem to put the blame on Trump: A CNN poll conducted last month found that 61 percent of Americans agreed with the statement that the Trump administration had “worsened” economic conditions. And in a survey released Monday by Harvard CAPS/Harris, 57 percent of voters said Trump was losing the fight against inflation.

That perception may not be entirely fair. Peter Coy, author of the economics Substack “Economics for Everyone,” told TMD that by several measures, wage growth has slightly outpaced inflation in 2025. While Trump’s campaign promises to bring prices down were “never realistic,” Coy argued, Americans tend to “fail to distinguish between the price level being higher versus inflation being higher.” In some ways, he said, the U.S. may still be getting over the shock of the early-2020s inflation spike.

But Heather Long, the chief economist at Navy Federal Credit Union, told TMD that consumers are facing pressures not easily captured by many measures of inflation and wage growth. Across five primary affordability measures—housing, child care, health care, electricity, and groceries—all but health care had outpaced wage growth over the last five years, Long noted. “You can decide not to buy a new phone or laptop this year. You can decide to drop your Netflix subscription,” she said. “You can’t decide not to pay your rent, and your electricity, and [your] groceries.”

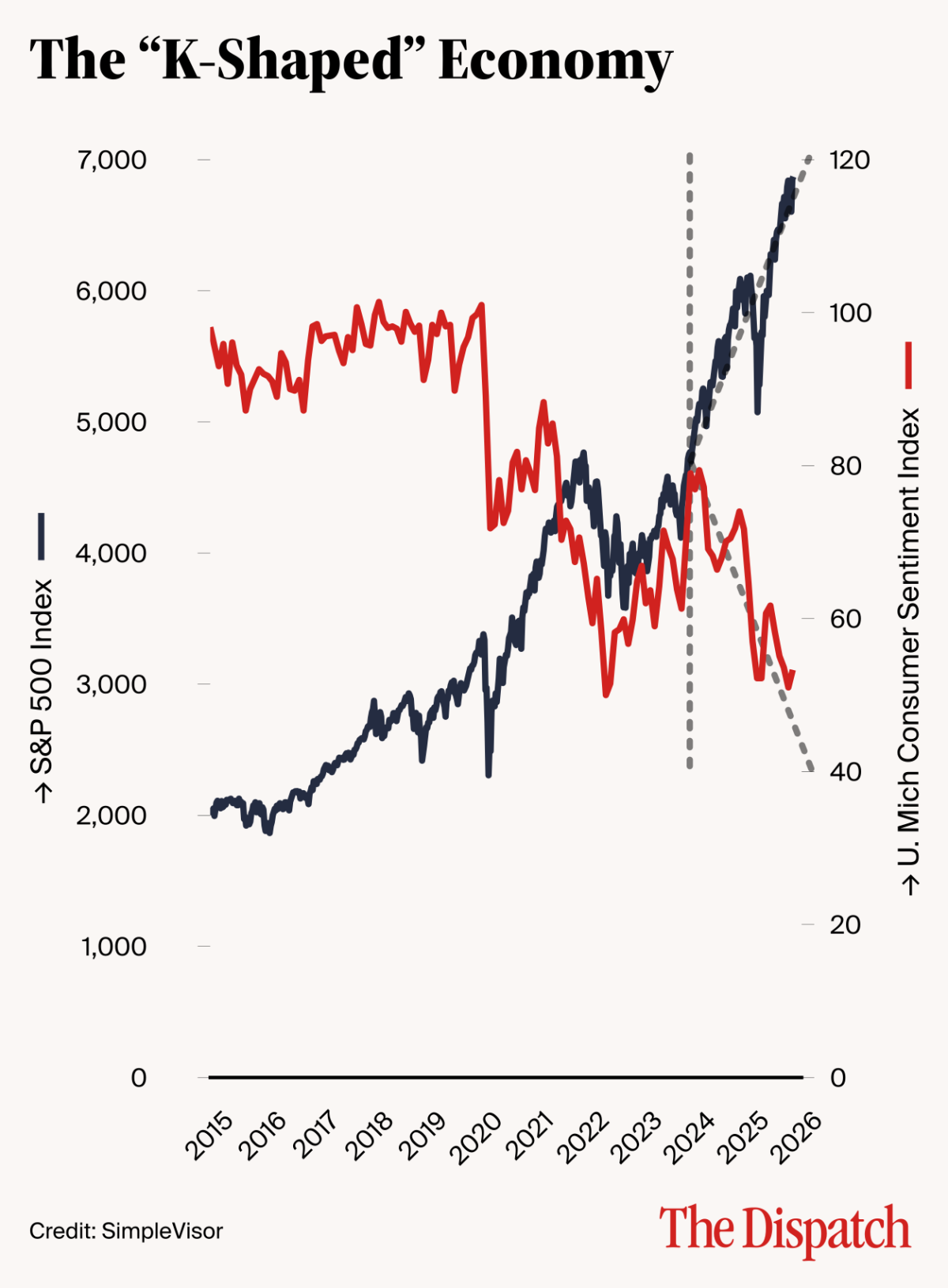

The ‘K-shaped’ economy.

The wealthiest consumers are driving a large share of U.S. spending, Long argued, which many commentators have termed the “K-shaped” economy. For example, retail sales on Black Friday last month were up 4 percent, similar to last year’s 4.3 percent jump—but that data was skewed by wealthier families’ spending more while households earning less than $40,000 spent notably less this year. According to Moody’s, in the second quarter of 2025, the top 10 percent accounted for 49.2 percent of consumer spending (though some argue this is misleading or outright false.)

“Consumption overall remains really robust, certainly stronger than I and pretty much everybody else thought when we were sitting in the spring looking at the tariff rates,” said Long. But that consumption is “being driven by a lot of stuff at the high end, and then a lot of smaller purchases.” Rather than a Black Friday rush to mid-price retailers like Banana Republic, holiday shopping is clustered around budget options like Ross and Nordstrom Rack, and luxury choices like Mr. Porter and Saks Fifth Avenue.

And the K-shape extends beyond consumer spending: A handful of companies dominate business investment and corporate earnings.

- Up to half of the U.S.’s 1.6 percent GDP growth in the first half of 2025 was driven by AI-related spending, according to an estimate by Barclays.

- Bank of America predicts that Microsoft, Amazon, Meta Platforms, and Alphabet (Google’s parent company) will have collectively invested $344 billion in capital expenditures during 2025, roughly equivalent to 1.1 percent of U.S. GDP.

- In the stock market, the “magnificent seven”—Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, Microsoft, Nvidia, and Tesla—account for more than a third of the S&P 500’s total market capitalization.

Homeowners who hold mortgages from the early stages of the pandemic or before, when interest rates were very low, are also getting wealthier at a faster rate than renters currently struggling with high housing prices, said Long. And households with significant investments in stocks (especially AI) and housing are driving much of the U.S.’s still-robust consumer spending. Rising AI stock prices boosted consumer spending by approximately $180 billion, through the wealth effect—in which a chunk of each dollar gained in wealth is spent on consumer goods like restaurant food or Christmas gifts—according to JPMorgan.

And little suggests that core goods will become more affordable in the coming months, even if growth remains steady and unemployment stays low. Without congressional action, enhanced federal subsidies for health insurance marketplaces will expire by the end of the month, increasing premiums for more than 20 million Americans. Home insurance costs are also rising, and a power grid strained by age, regulation, and new AI data centers is driving up electricity costs.

The Federal Reserve.

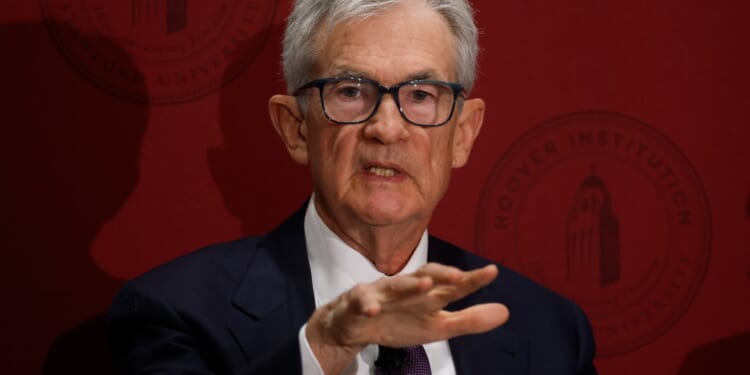

Trump has repeatedly blamed Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell—and his unwillingness to cut interest rates as quickly as the president wants—for Americans’ economic dissatisfaction. But even if the Fed were to surprise market watchers and hold rates steady this afternoon, the president won’t have to deal with Powell for much longer. White House National Economic Council Director Kevin Hassett, who has advocated for lowering interest rates at a faster clip, is reportedly Trump’s top choice to replace Powell as chair when his term ends in May, adding another dovish voice to the rate-setting committee in the coming months.

It’s unclear, though, whether lower interest rates would assuage Americans’ affordability concerns, Beckworth noted.

“The risk is that it’s not a regular rate cut,” he said, pointing to a recent paper by University of Maryland economist Thomas Dreschel. The paper found that rate cuts imposed under political pressure from the president only raised prices while doing little to boost real economic activity.