You’re reading the G-File, Jonah Goldberg’s biweekly newsletter on politics and culture. To unlock the full version, become a Dispatch member today.

Dear Reader (even those of you who enjoy a nutritious spoonful of Parwill),

Because of my misspent youth, I have a penchant for explaining things in terms of movies and TV shows. I don’t necessarily recommend it, but it’s worked pretty well for me. One of the most successful cover essays I ever wrote for National Review was about the movie Groundhog Day. I still get nice notes from high school teachers, college professors, and the occasional pastor about how they use it in classes. My recent return to the font of wisdom that is Animal House elicited an enormous amount of positive feedback.

Normally, I try to illuminate philosophical stuff rather than engage in mere punditry. (Though if someone wanted to count up the number of times I’ve referenced Stripes or The Silence of the Lambs in columns, it might be a little embarrassing for all concerned). That’s because movies are essentially just stories, and successful stories not only tell us something about human nature, they rely on certain eternal truths about human nature, starting with the fact that our brains are wired to understand reality through stories. Movies are an important idiom of modern discourse, including political discourse. Not long after we launched The Dispatch, I realized that a lot of our younger staffers weren’t familiar with cinematic references that are part of the lingua franca of our politics almost as much as martial metaphors are. So I wrote a little guide to movies that have shaped political language.

Un plan sencillo.

I could go on, but let’s get started with the punditry.

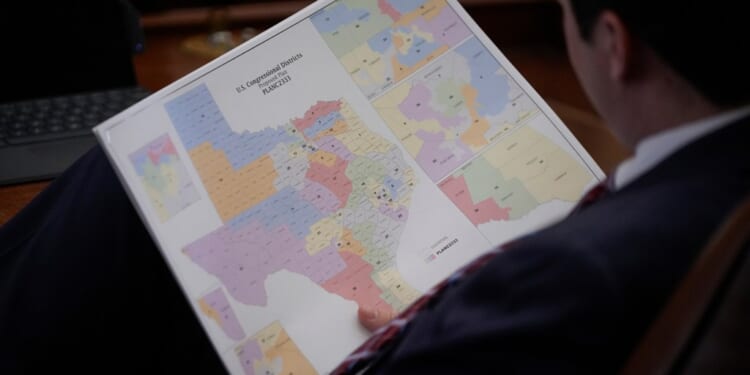

The Republican effort to game the system for a few extra congressional seats looks to be backfiring spectacularly (listen to the latest episode of Advisory Opinions for a full breakdown). A federal court ruled this week that the new Texas congressional districts were constitutionally invalid and threw them out.

A quick recap: President Donald Trump, for perfectly understandable reasons, really doesn’t want the GOP to lose the midterms, so he asked Texas to redraw a bunch of districts so they could pick up some more seats. After Texas initially declined, Trump turned up the pressure and had the Justice Department write a letter to the Texas governor and attorney general, asserting that four congressional districts “constitute unconstitutional racial gerrymanders.” Texas must give Hispanics in these areas greater representation in Congress.

Read The Morning Dispatch Free

We’re taking our flagship newsletter out from behind the paywall this week. If you’re looking for a greater understanding of the biggest stories shaping your world, give The Morning Dispatch a try for free—because insights beat outrage.

Stories We Think You’ll Like

The problem? Well, for starters, the letter was what legal scholars call “not good.” I’m no lawyer, but when a (Trump appointed!) judge says this in his opinion about your letter, there’s clearly a problem:

It’s challenging to unpack the DOJ Letter because it contains so many factual, legal, and typographical errors. Indeed, even attorneys employed by the Texas Attorney General—who professes to be a political ally of the Trump Administration—describe the DOJ Letter as “legally unsound,” “baseless,” “erroneous,” “ham-fisted,” and “a mess.”

A three-judge panel ruled that a purely partisan gerrymander would have been fine (icky, norm-breaking, etc., but legal). But using race to redraw the districts was constitutionally impermissible.

You see, because the Trump administration and Gov. Greg Abbott were so embarrassed by the obviously true charge of nakedly partisan norm-breaking, they decided to wrap themselves in the DOJ’s argument that this was all about race, not politics. The court’s decision has a long excerpt from a transcript of Abbott insisting to CNN’s Jake Tapper that this was all about race stuff, not partisanship. As the opinion summarizes:

When given an opportunity to publicly proclaim that his motivation for adding redistricting to the legislative agenda was solely to improve Republicans’ electoral prospects at President Trump’s request, the Governor denied any such motivation. Instead, the Governor expressly stated that his predominant motivation was racial: he “wanted to remove … coalition districts” and “provide more seats for Hispanics.” The fact that the racially reconfigured districts would happen to favor Republicans was, to paraphrase the Governor’s own words, just a fortuitous coincidence.

But wait, there’s more. The idea that this “fortuitous coincidence” would help Republicans was based on the assumption that Trump’s legitimately impressive success in 2024 (48 percent overall) with Hispanics was permanent.

As I wrote recently, this assumption looks increasingly shaky. It’s pretty obvious that most of those Hispanic voters hadn’t converted to full-on MAGA. They were nostalgic for the pre-pandemic economy of the first Trump term. Moreover, the idea that large numbers of Trump-supporting Hispanics who believed that his immigration enforcement efforts would concentrate solely on violent criminals and drug gangs would overlook not just a disappointing economy, but months of harassment and deportations of hardworking and law-abiding Hispanics, regardless of their immigration status, was preposterous.

In short, Hispanics, broadly speaking, weren’t MAGA voters, they were traditional swing voters, and Trumpworld took them for granted.

Trump’s polling with Hispanics has cratered, and the gains the GOP made in 2024 were more than reversed in the recent off-year elections (Democrat Mikie Sherill won the New Jersey governor’s race with 68 percent of the Hispanic vote. Fellow Democrat Abigail Spanberger got 67 percent in Virginia). If current polling and economic trends continue, it’s entirely possible that these new Hispanic districts in Texas would actually vote for Democrats rather than Republicans. And because gerrymandering invariably dilutes safe seats to make other seats more competitive, one can imagine a wave taking out some otherwise secure Republicans.

As Mary Ellen Klas of Bloomberg recently wrote, “Republicans are hardly going to admit it, but they should evaluate whether Trump’s push to ignite a redistricting arms race may have made it easier for a blue wave to wipe out more Republicans than if they had left their maps alone.”

The Supreme Court may overrule the three-judge panel, despite the DOJ’s and Texas GOP’s manifest legal cockuppery. So we might find out.

But the cockuppery doesn’t end there. When the Texas judges ruled this week that the new districts were invalid, I thought it was possible that the court actually saved the GOP from an embarrassing debacle. But then I remembered that the hullabaloo over the redistricting prompted California Gov. Gavin Newsom to push a successful referendum to gerrymander five new Democratic seats in his state. So, no matter what, this scheme backfired. Indeed, many states that got on the redistricting bandwagon are now quietly receding, Homer Simpson style, into the shrubbery.

Let’s go to the movies.

One of my favorite movies is A Simple Plan. A quarter-century ago, I wrote that it was one of the most conservative movies of the 1990s. The premise of Sam Raimi’s brilliantly understated movie is that things can fall apart really quickly when you ignore some basic, hard-learned rules about life.

A Simple Plan is about three Midwestern guys who find a pile of money in the woods. Bill Paxton, who plays a happy accountant married to a very pregnant and happy wife, immediately suggests calling the cops. Keeping the money would be stealing.

Au contraire, the town drunk replies, “It’s the American dream in a goddamned gym bag.”

Paxton snaps back: “You work for the American dream, you don’t steal it.”

“Then this is even better,” the souse replies. The other two convince Paxton and then devise “a simple plan” for keeping the money.

From this modest premise, a profoundly conservative lesson is taught: Do the right thing. We have very humble moral rules for a reason.

One of the central insights of conservatism (and Hayekian liberalism) is that we are standing on the shoulders of the generations that came before us. We live in a civilization constructed out of Chestertonian fences. The trial-and-error experience that has gone into life’s simple rules of thumb stretches back to the first caveman who accidentally cooked a haunch of bison. Most of us didn’t learn from experience that you shouldn’t eat a random mushroom in the woods. Someone died to teach us that lesson. We take the existence of money for granted, but money as a medium of exchange is an invention. The thinking that went into it is forgotten by most people, but the institution endures because it solves all manner of problems we can’t even wrap our heads around. The same thing holds with good manners, court procedures, traffic signals, and, yes, congressional redistricting. Bill Paxton’s character didn’t know all the ways this simple plan could or would lead to misery and folly. But in his gut, he knew that it was a bigger gamble than his simplistic compadres thought.

Right now, a bunch of people on the right are debating whether or not to play footsie with antisemites and bigots. Their motivations cover the waterfront from the mercenary to the mischievous to the malign. But they all share a common ignorance. The rules against indulging this demonic idiocy were hard-learned by scores of generations, but parts of the new right are as contemptuous of the lessons of the past and the moral rules of thumb they’ve inherited as people on the left have been for generations.

Others on the new right have convinced themselves that they stand on the shoulders of idiots. The Constitution? We can do better. The free market? We’ve got a simple plan to out-think it. Following that simple plan about tariffs has convinced 73 percent of Americans that tariffs have raised their prices.

The seduction of simple plans stems from a lack of imagination about all that can go wrong in life and contempt for old-fashioned nostrums about the ways things are supposed to be done.

Edmund Burke’s predictions about what the French Revolution would lead to rested on his understanding of the fragility of peace and stability and the corruptibility of human nature. The Soviet Union was a cathedral of simple plans to create a socialist economy and even a New Soviet Man. And, just as Burke predicted, when ideologues act on their contempt for the past, believing that they can just start over at Year Zero and reinvent every custom and institution, fueled by the arrogance of their intellect, not only do things go awry, but the simple planners redouble their efforts to force reality to conform. Their simple planning gives way to a form of power-worship that assumes they can just force the reality they want.

Many on the right love to talk about “dynamic scoring” when it comes to budget forecasting, but they resort to static scoring of politics. They think their actions will not invite counter-actions. The problem with norm violations isn’t just that they are bad on the merits, it’s that they invite more norm violations. Break the custom of redistricting every 10 years and you invite others to break it too. Assume that all of the factors in your simple plan will hold constant—like Hispanic voters who vote Republican once will never stop voting Republican—and life will teach you a lesson.

Another kind of movie I dearly love is the long-con movie. But I love those films because they are a fantasy, often more improbable than any sci-fi movie. The long-con movie works on the premise that you can plan for every eventuality and every human reaction to new events. I love The Sting, the very underrated Diggstown, and similar movies because they are fantasy.

A lot of people think politics is like a long con. Every twist and turn was planned. Every result is what “they” wanted to happen. The “they” can be “billionaires” or “the Deep State” or, sadly, the Jews.

But that’s not how politics works. The only political leaders who get exactly what they want—and they are rare—are ones willing to use fear and violence to get it. Napoleon could take Vienna because he had an army. Saddam Hussein could rule for so long because he followed the rule that the solution to solving a problem was removing the head of the person behind the problem. Stalin didn’t win arguments because he was a great debater.

In democracies, however you want to define that term, plans never survive contact with the opposition perfectly intact. Politicians announce plans every day, and the world responds with shrugs, yawns, or new plans to derail those plans.

This is the system the founders envisioned: a never-ending argument about the best way forward. Everyone has a plan. But only the plans that involve persuading people to sign up for them have a chance. That usually requires changing the plan on the fly. And even the best and most popular plans can run afoul of the law or the Constitution, and—when the system is working—that means revising the plan or just starting over.

“To live is to maneuver,” as Whittaker Chambers said. But his point wasn’t some Nietzschean bromide about how everything is permitted and nothing is forbidden. We maneuver along the long path of accumulated wisdom through the dense jungle of human nature, hopefully with an eye to the breadcrumbs our ancestors dropped along the way. When we follow a simple plan that calls for leaping over the guardrails of the path, things will inevitably go awry.

People who love Trump celebrate the fact that he is a “disrupter” who leaps off the path. Trump practices what Michael Oakeshott called politics as the crow flies, but not in service to some ideological simple plan. His simple plans always involve self-interest. He shares the same contempt for the hard-learned lessons of the past that live with us as norms, rules, customs, and even law that the Year Zero ideologues sneer at. Yes, it’s worked remarkably well for him, which is all he cares about. But his story is not over, and his definition of self-interest only glancingly takes into consideration what is actually good for the country or how he will be remembered. He sees the presidency like he’s the mastermind of a long con. When he’s told that this is not how presidents are supposed to act, he fingers his gold ingots and gazes at pictures of his Qatari Boeing 747-8 aircraft and says, “Well, this is better.”

Various & Sundry

Canine Update

Not a lot to report this week, save that Pippa is becoming evermore recalcitrant in the mornings. I don’t blame her, really. She’s creaky, and it’s cold and dark out (indeed, it’s so dark, I can’t even get good video most mornings of her “five more minutes” routine). Also, Pip thinks the mean dogs lurk in the darkness. So I get caught in a pincer movement between Zoë’s enthusiasm and Pippa’s lethargy. If Zoë could wait without arooing at me, I could make coffee and wait a while longer. The added problem is that Pippa tends to start her wake-up clock only after I wake her. So delaying departure doesn’t obviate the need for negotiating her participation. The real solution would be for The Fair Jessica to wake up much earlier, but for reasons that should be obvious, I cannot make that proposal. TFJ and I went on a short trip over the weekend, and the girls had a great sleepover at Kirsten’s (with a few hiccups). Appeasement continues, as does Gracie’s A-level slumbering.

The Dispawtch

Member Name: Blair M. Gardner

Why I’m a Dispatch Member: I began reading articles from Jonah Goldberg and Kevin Williamson (and Stephen Hays) years ago. When I learned that they were beginning a new venture that sought to adhere to the same journalistic standards—clarity in expression and analysis, a consistency in philosophical outlook, an avoidance of rank partisanship—that I had always admired in their writing, I knew that the subscription would be well worth the price. I have not been disappointed. With additional analysis by Scott Lincicome and Nick Catoggio, plus the growing number of contributors, it is the best publication I have found devoted to the topics I believe any informed person needs to follow. The weekend articles on issues of religion and faith are a wonderful bonus. I have recommended The Dispatch to many friends and family.

Personal Details: I am a retired lawyer living with my wife in Northwest Indiana. I have been fortunate to have lived in many places in the U.S.—born in Pennsylvania, grew up in Virginia, college in New England, employment over my career between West Virginia and the Midwest, with lots of time spent in Wyoming—and I have found something to love and admire about the people in each of these places. As a conservative and traditional Republican who struggles to make sense of what has happened in our political culture, I try to recall all the good people I have met in my work. I have also been encouraged by the members of The Dispatch, who are unafraid to share their opinions and for the civil manner in which most of us are able to engage with one another.

Pet’s Breed: Domestic shorthair shelter rescue

Gotcha Story: We lost our previous cat on Thanksgiving Day 2022. Unknown to me, my wife must have adopted a “no home without a cat” rule sometime earlier in our 35 years together, because the next day she drove to an animal shelter in the neighboring county in search of a new cat. She found Princess, who had been found wandering the streets of Hobart, Indiana, and had been picked up 10 days earlier. She described Princess as a cat that seemed intent on grabbing her attention by entertaining her with her antics, so she brought her home that afternoon.

Pet’s Likes: Verifying that gravity is present in our home by rolling balls and stuffed animals down the stairs. Sitting in the window and watching chipmunks, birds, and squirrels in the woods behind our home. Tummy rubs.

Pet’s Dislikes: Fireworks during sporting events at our nearby high school.

Pet’s Proudest Moment: Climbing on top of our kitchen cabinets by a technically challenging floor-to-countertop-to-refrigerator-to-cabinet maneuver.

A Moment Someone (Wrongly) Accused Pet of Being Bad: My wife when she found Princess on top of the cabinet after she had just been brought home.

Do you have a quadruped you’d like to nominate for Dispawtcher of the Week and catapult to stardom? Let us know about your pet by clicking here. Reminder: You must be a Dispatch member to participate.