You’re reading Capitolism, Scott Lincicome’s weekly newsletter on economics. This newsletter has been unlocked for all readers. To read all our reporting and commentary, become a Dispatch member today.

Zohran Mamdani’s recent victory in New York City’s mayoral race has sparked a debate about whether the city’s billionaire class will abandon Gotham once and for all. The 34-year-old democratic socialist campaigned on an ambitious (and costly) “affordability” agenda: freezing rents on 1 million apartments, raising the minimum wage to $30 per hour by 2030, establishing government-run grocery stores and universal child care—and funding it all through higher taxes on corporations and the wealthy. As a result, several ultrarich residents vocally opposed Mamdani’s election, noting that his big government plans would likely add, not remove, burdens for most New Yorkers and would push the city’s super-elite to relocate elsewhere.

Since Mamdani’s big win, some of those billionaires have already walked back their threats, and several commentators have gleefully noted that the rest of the city’s elites need—or simply love—NYC too much to abandon it for greener, cheaper pastures. Yet this focus on the city’s billionaire class mostly misses the point. Aside from the most extreme and unrealistic of Mamdani’s wealth-confiscating plans, the flight risk arising from his proposals policies was never about billionaires; it was about their employees—the higher-earning New Yorkers who can’t easily absorb the higher costs and greater inconveniences that Mamdani’s plans will produce but can move to places, near and far, where life is a little easier. These HENRY (“high-earner-not-rich-yet”) workers form the backbone of New York’s economy and, thanks in large part to remote work, have been increasingly heading for the exits. Mamdani’s policies could accelerate their departure, harming New York along the way.

What Mamdani Can (and Can’t) Actually Do—and What It Will Cost

Before we get to that, however, it’s important to note that political realities will likely limit which policies Mamdani can actually implement, even with a big mandate. As our Dispatch colleagues reported last week, he probably won’t fulfill his signature promise to raise income and corporate taxes because “under state law, New York City cannot raise the city income tax without Albany signing off,” and New York Gov. Kathy Hochul has already rejected the idea (in part because she’s facing her own reelection in 2026). Other proposals, such as free buses and that $30 hourly minimum wage, also need state approval. And without new tax revenue, other parts of Mamdani’s agenda—free child care, tons of new public housing—-face major fiscal constraints because of an already-large budget gap (caused in part by the city attracting fewer American millionaires between 2010 and 2022 than places like California, Texas, and Florida—more on that in a second).

Stories We Think You’ll Like

Several of Mamdani’s other plans have a better shot of being implemented in some form, albeit likely watered down. His promise of a four-year freeze on rents for the 40 percent of New York City apartments that are rent-controlled, for example, faces legal hurdles. But it’d be surprising if the city’s nine-member Rent Guidelines Board, which Mamdani will surely influence via new appointments and political strong-arming, doesn’t pass some form of expanded rent control. New York City mayors also have substantial authority over appointments, agency priorities, and enforcement, so we should also expect his administration to push the city’s child care, education, and municipal workforce policies as far left as they can feasibly go in the near term, and for him to use the bully pulpit to agitate for longer term reforms at the city and state level.

Yet even a watered-down version of Mamdani’s agenda—partial rent freezes, higher minimum wages for city contractors, more union mandates, expanded public child care, less choice in education, etc.—would impose new burdens on both businesses and most residents, especially HENRY workers who are too rich to qualify for government benefits but too poor to simply shrug off higher costs.

Housing provides the most obvious example. Little chance that a HENRY couple would qualify for new public housing or “affordable” units, either built by public-private initiatives or required to be set aside for low- and middle-income workers. (As an aside, various estimates show that requiring union labor for new “affordable” housing in NYC would raise construction costs by 30 percent or more, with some Manhattan units costing upward of $1 million each! Hence, the snarky scare-quotes.)

Any expansion of rent control, meanwhile, will surely harm more New Yorkers than it helps. As we’ve discussed, the evidence on rent control is overwhelming and unambiguous: It helps a handful of local renters but reduces housing supply, decreases maintenance, distorts markets, and ultimately makes cities less comfortable and affordable for everyone else. Renters competing in New York’s unregulated market would face higher prices when, for example, frozen rents push already-struggling buildings into foreclosure. (The city’s Rent Guidelines Board data shows that 10 percent of rent-regulated buildings—totaling more than 64,000 units—are already operating at a loss.) The additional supply crunch would force HENRYs to bid against each other—and people with even deeper pockets—for whatever housing is left, pushing prices even higher.

New child care policies would likely cause similar problems. The average cost of private, center-based infant care in New York City already exceeds $25,000 annually, while less-regulated “family care” is still more than $20,000. Many New York families with two children often pay more for child care than rent! Mandating higher wages for child care workers while expanding access through new city-run centers will surely serve some people (though, research cautions, probably not well). Yet it’s bound to increase the cost of both public and private child care in the city, with HENRYs—reluctant to use public daycare or ineligible due to income limits driven by politics or the aforementioned fiscal realities—again on the losing end.

For starters, boosting wages for public child care workers would—along with mandatory benefits and union requirements for city-funded facilities—not only increase the costs of that care but likely pull workers and resources away from private facilities used by wealthier families who won’t qualify for public assistance. (And, as we’ve discussed, U.S. immigration restrictions will surely limit any replacements.) Throw in New York’s already high regulatory costs, and the annual private child care expense for HENRYs could easily exceed $30,000 per child once this “affordability” agenda is enacted.

Other policies, such as higher minimum wages, involve similar trade-offs, with HENRYs usually on the losing end of the trade (higher prices, fewer choices, etc.). Even if many of Mamdani’s plans aren’t implemented, moreover, the mere signaling effect of his agenda also matters: Upper-middle-class professionals planning where to live and raise their families might be unwilling to wait to see if economic gravity once again exists. Instead, they might just leave.

So, They’ll Leave

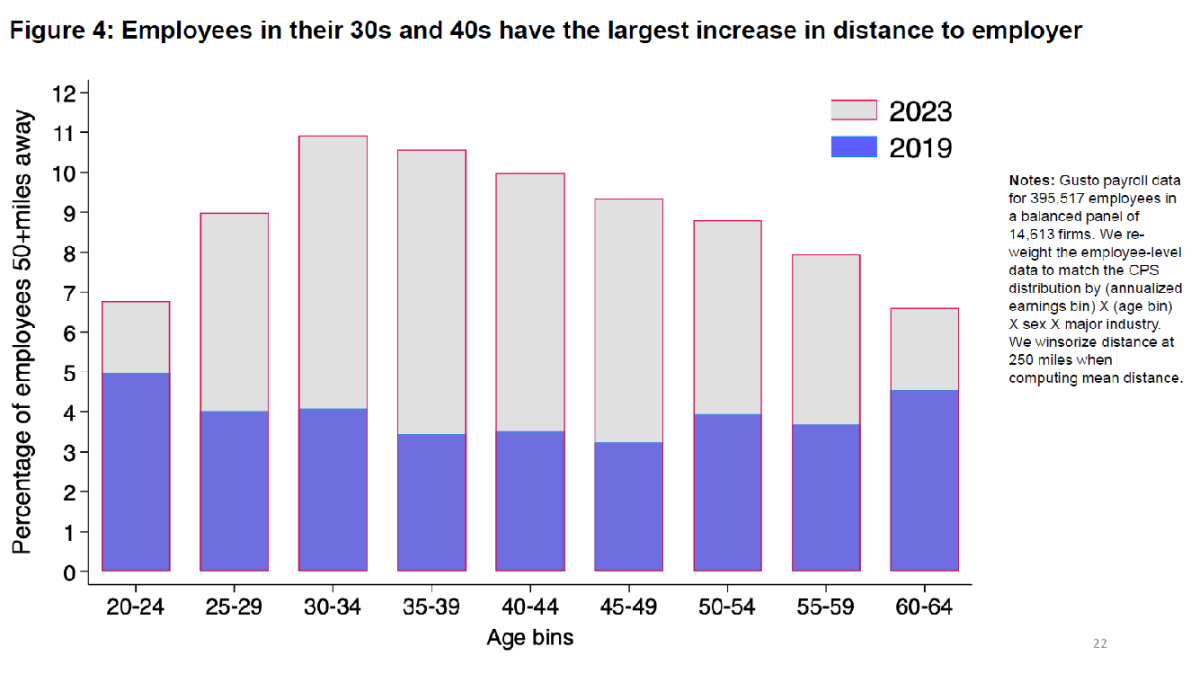

New research shows, in fact, that HENRYs—aided by remote work—are already leaving New York and other big cities for these very reasons. As we’ve discussed repeatedly, the pandemic-era remote-work boom allowed millions of Americans to flee unaffordable places and live where they want to live, instead of where their employer happened to be located. A new paper from Stanford-affiliated economists confirms these trends in ways that are particularly notable for a place like NYC. It shows that remote work has expanded the average distance between an employee’s home and her employer worksite (from 15 miles in 2019 to 26 miles in 2023) and tripled the number of employees living at least 50 miles from their employers. But these effects weren’t uniform; they were concentrated among workers in their 30s and 40s …

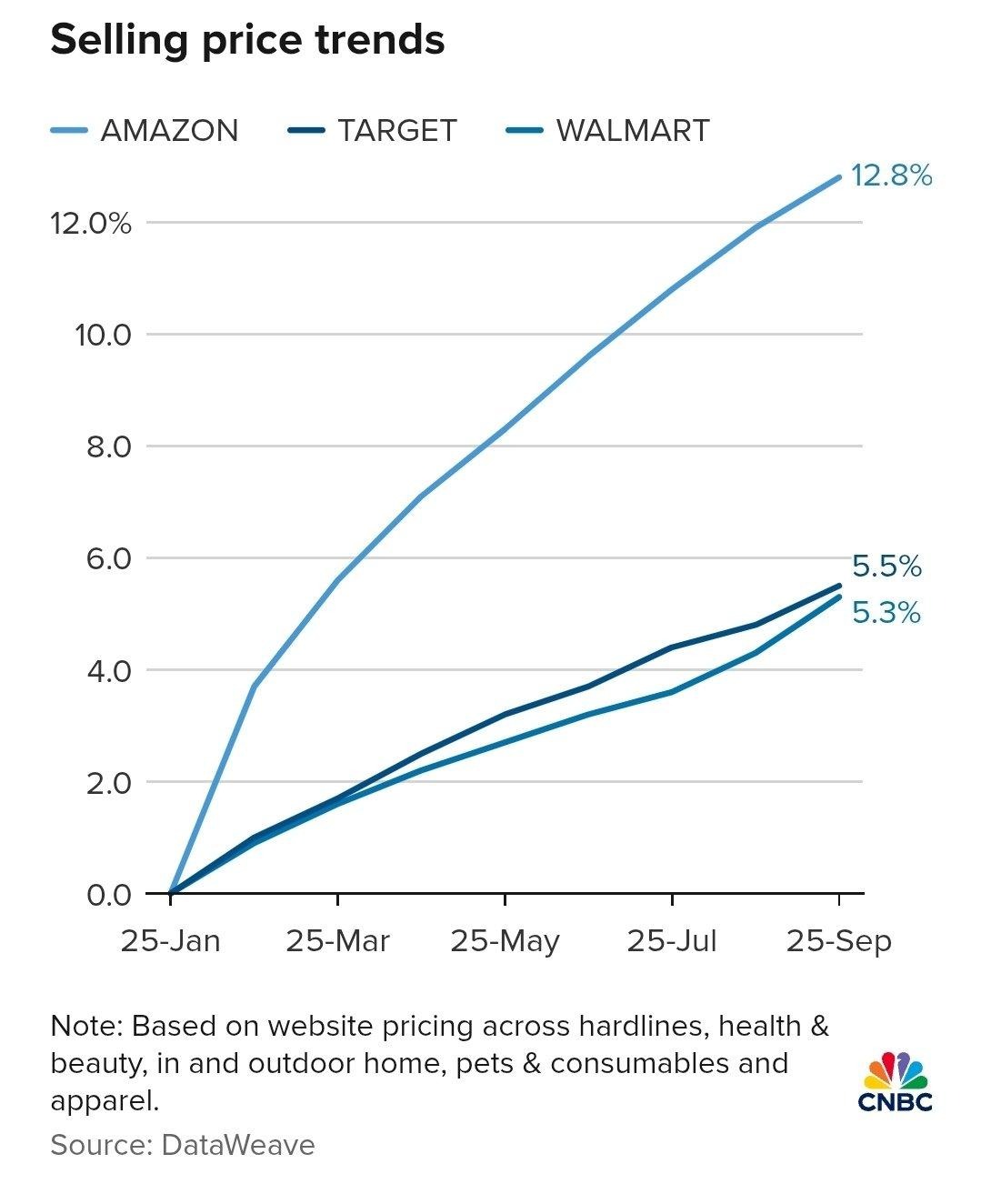

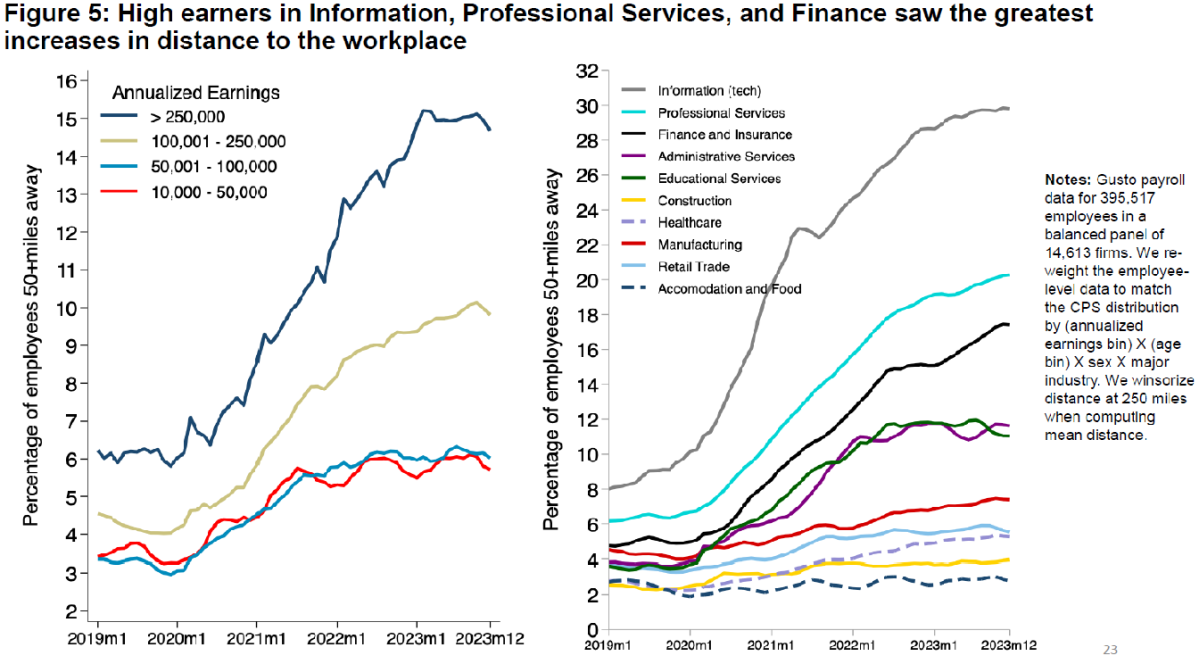

… And among highly paid workers in industries like finance and insurance, information, and professional and business services:

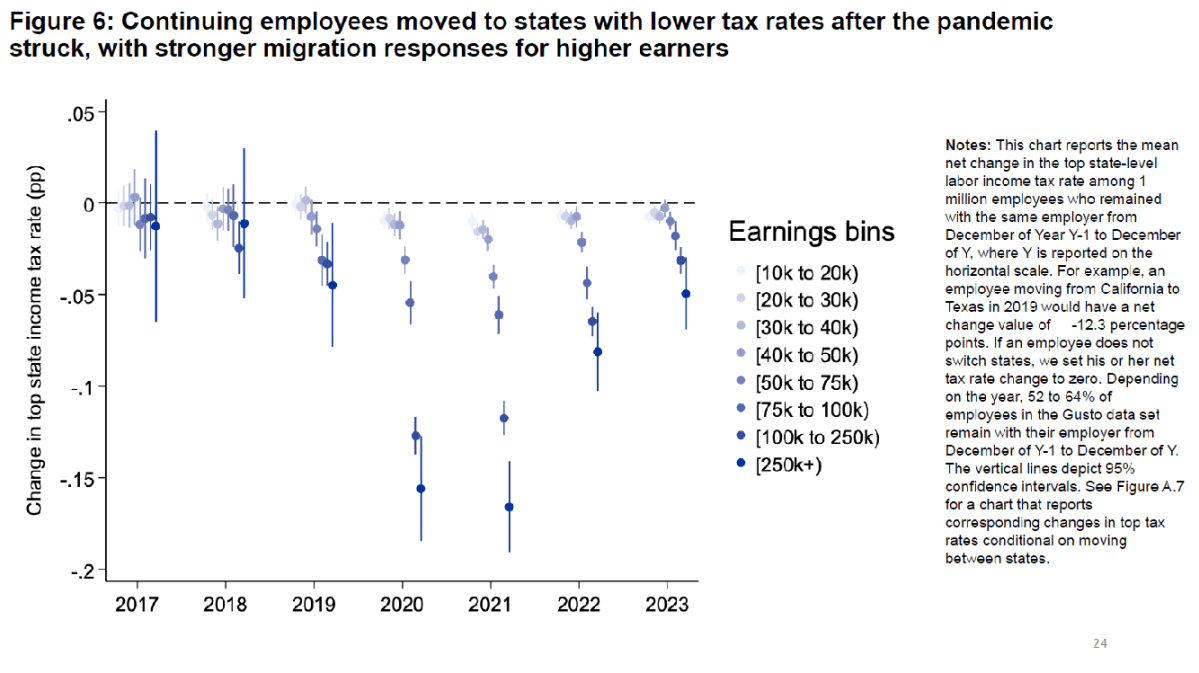

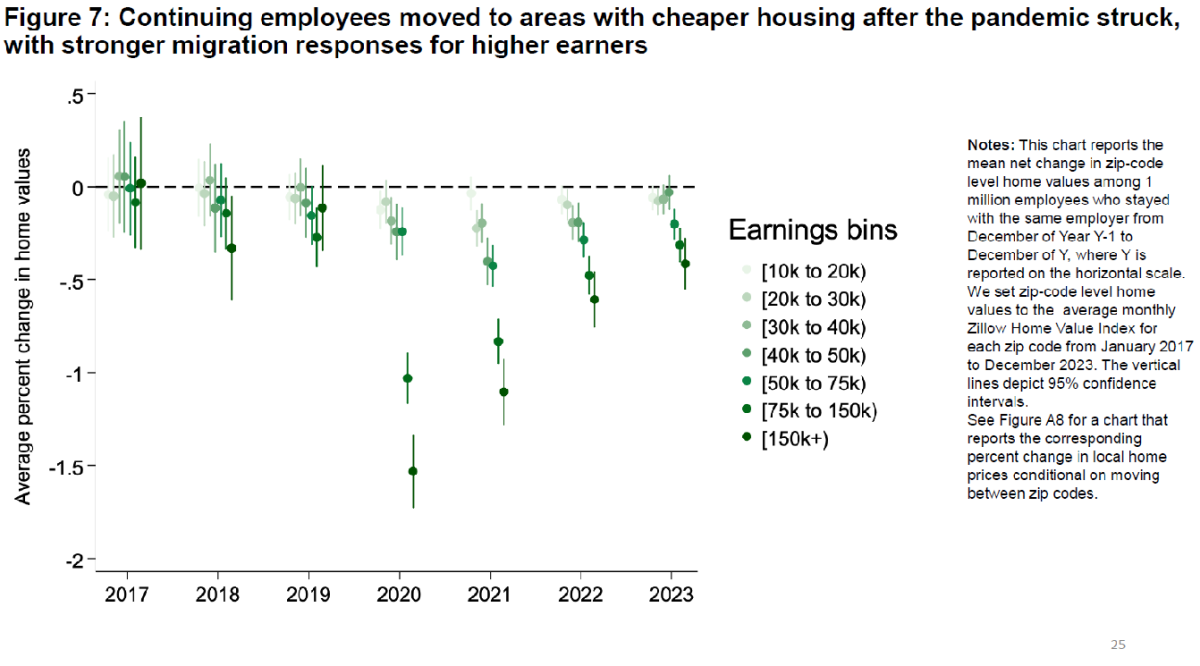

Finally, the researchers find that these new movers were motivated by housing costs and taxes, with effects again concentrated among higher earners:

All of this makes intuitive sense: Workers in their 30s and 40s tend to be ones who are raising (or contemplating) families, making long-term residential decisions, and thus are particularly sensitive to the cost of living. Higher-paid “knowledge workers” also tend to have jobs that more easily allow them to live farther from their workplaces (and have the resources to make such a move happen). The cost savings from such moves, the Stanford paper calculates, are substantial: Employees who made more than $250,000 a year, moved between states in 2020, and stayed with the same employer lowered their state tax rates by an average of 5.2 percentage points, or $15,000 in annual tax savings for someone earning $300,000. Mobile workers making at least $150,000, meanwhile, enjoyed a 16 percent reduction in their local housing costs—and likely even greater gains on a price-per-square-foot basis, as homes tend to be larger where space is cheaper.

These findings* have clear implications for a place like New York—and for Mamdani’s agenda. The city, in fact, comes up twice in the Stanford paper because it’s not only expensive but also contains large shares of just the type of people who are particularly willing and able to move because of living costs. As the paper’s authors put it, “Outmigration pressures are most acute for cities with high housing costs that are situated in high-tax states, especially cities that also have high employment shares in industries with remote-suitable jobs.” That’s NYC in a nutshell.

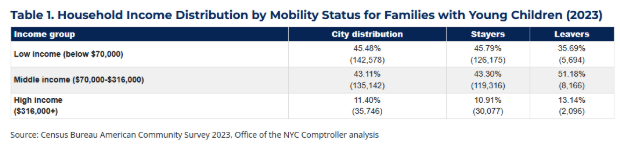

Child care costs are unmentioned in the Stanford paper but could play a role too, especially in New York. A two-child HENRY family living in the city can’t reasonably spend $70,000/year on child care without seriously contemplating a change in scenery. And the city’s government recently found, in fact, that New York’s “population losses are concentrated among families with children,” with middle- and high-income families—households that “often exceed income limits for public assistance programs while still struggling with the combined costs of living in NYC”—disproportionately leaving:

The Exodus Already Underway

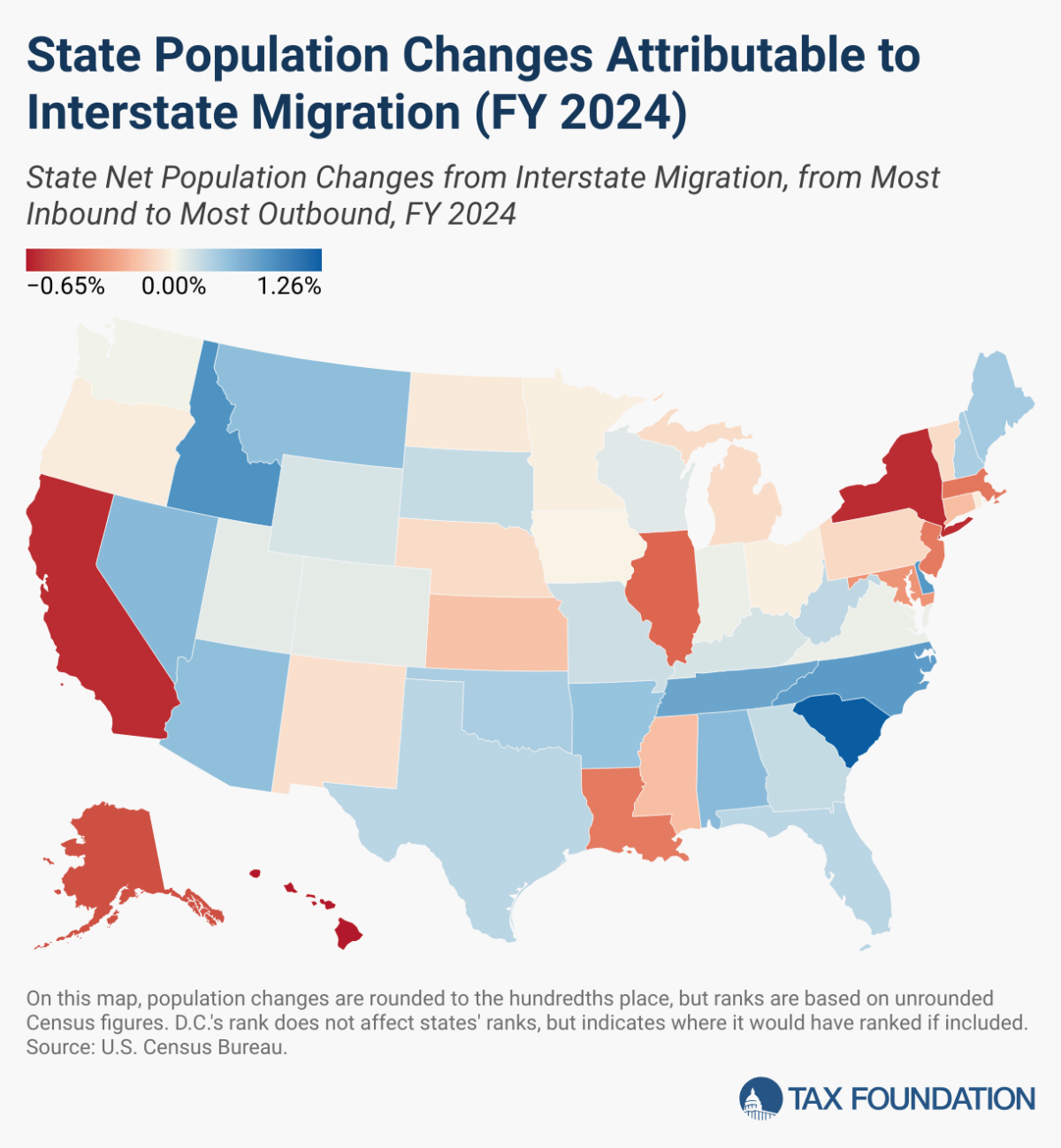

The Stanford paper is hardly the only one to find increasingly mobile American workers moving from higher-cost to lower-cost places. Along with the research we’ve already discussed, for example, U-Haul’s 2024 migration data show the biggest gainers last year were Dallas, Charlotte, Phoenix, and Austin—not coincidentally, metros with lots of housing and lower costs of living. A recent Tax Foundation analysis confirms the trend: Americans are systematically relocating from high-tax, high-cost states to low-tax alternatives. For the second consecutive year, South Carolina saw the greatest population growth from domestic migration, while New York lost 0.61 percent of its residents to other states, ranking 49th nationally.

This doesn’t mean, however, that disgruntled New Yorkers (or potential transplants) are all necessarily moving to the Carolinas, Texas, or Florida (though lots of them are). They’re also moving upstate, up or down the turnpike, or just across the river. Around 75,000 New Yorkers, for example, relocated to New Jersey in 2024—a 12 percent increase from the previous year. Philadelphia, the Times reported earlier this year, is “the new hot spot for New Yorkers” looking for a lower-cost life. And Connecticut home prices have far outpaced the national average in recent months, signaling that pandemic-era moves are continuing (and backing recent anecdotes about New Yorkers continuing to leave the city for Bridgeport, Hartford, Stamford, and the like).

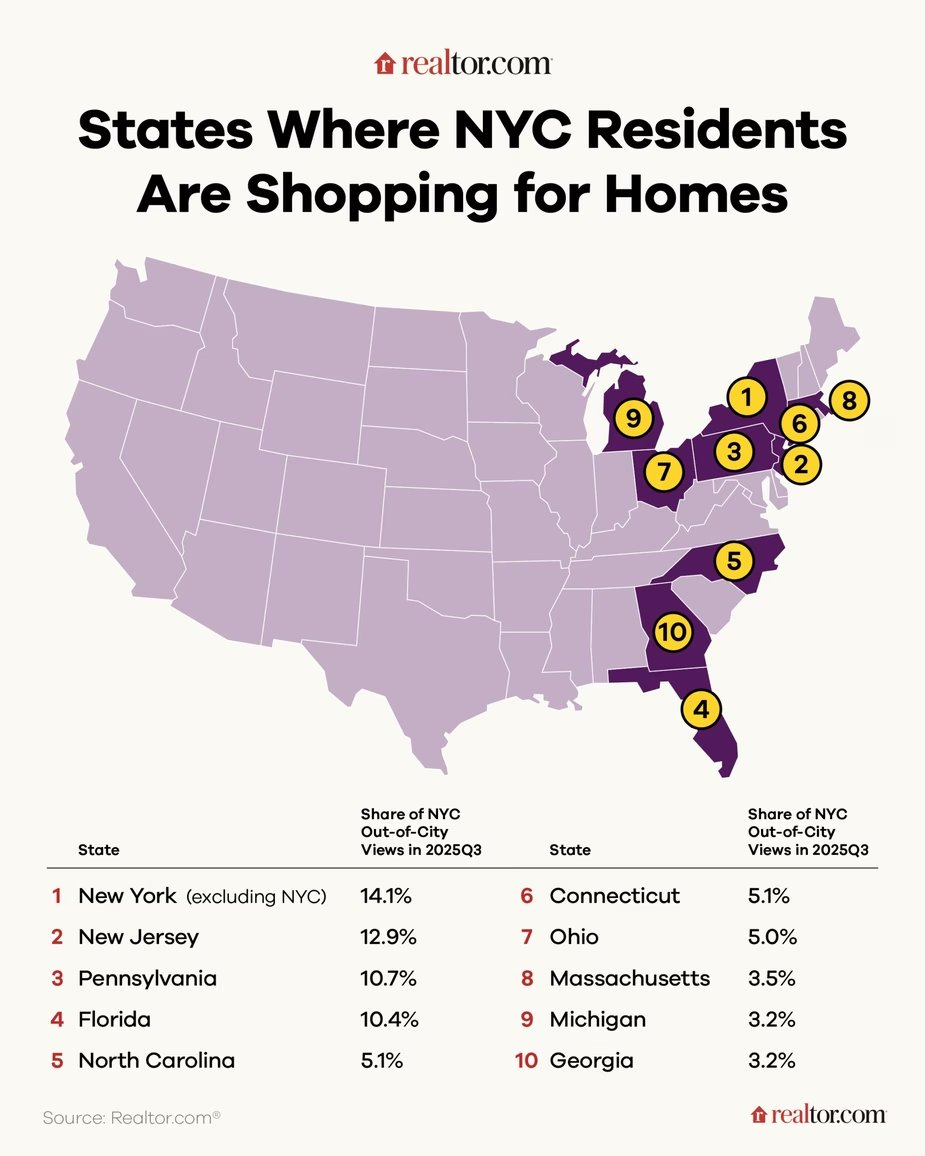

The math underlying any such decision is straightforward: Why pay $4,000 to rent the average one-bedroom apartment in NYC when you can pay the same monthly amount to own a $650,000 home in a New Jersey community that has direct and relatively quick train service into Manhattan (when a hybrid worker might need it). Throw in modestly lower taxes, decent schools and cheaper child care, added public safety, and various conveniences, and it’s a pretty easy call for many New Yorkers who can afford to make such a move. As the National Association of Realtors just concluded, New York City residents really are headed toward the exits, “and their top destinations ensure a cheaper life”:

New Mamdani tax, housing, child care, and other policies adding to these already-high pressures are sure to hasten the exodus.

Summing It All Up

Wealthy elites often have specialized needs—access to capital markets and clients, proximity to their businesses, cultural and social networks—that New York City uniquely provides, and higher costs usually won’t offset these advantages. But cities don’t run on billionaires alone. They run on the accumulated contributions of all residents, including hundreds of thousands of HENRY professionals who work in New York’s knowledge industries, patronize its businesses, pay substantial taxes, and do it all without government help or the perks that only the ultrarich can afford. For these folks, living costs matter, and—thanks to remote work—they’re increasingly willing to leave when life gets too expensive or uncomfortable, taking their tax dollars with them. (And, if recent news out of Connecticut is correct, the exodus may have already begun.)

The silver lining, if there is one, is that, by eroding New York City’s tax base, HENRY departures would make Mamdani’s budget-challenged plans even more challenging. As the Stanford researchers note, the loss of high-earning employees has “potent fiscal consequences for states and localities,” with migration from high- to low-cost states significantly reducing income tax collections in the former (and overall) between 2020 and 2023. Other studies, meanwhile, show that outmigration from New York—driven mainly by NYC departures—has reduced taxable incomes there by tens of billions of dollars. Lower tax revenues would mean less money available for the social programs Mamdani wants to implement. Lose enough HENRYs, and the math stops working altogether.

Ironically, it might be this flight risk that prevents many of Mamdani’s policies from being implemented in the first place. That’s another benefit of people voting with their feet— and of remote work helping them do it.

*And, before you ask: Despite all the return-to-office talk, the latest data for November 2025 show work-from-home rates to be stable, with only a small drop this year and particular strength in finance, IT, and professional services.

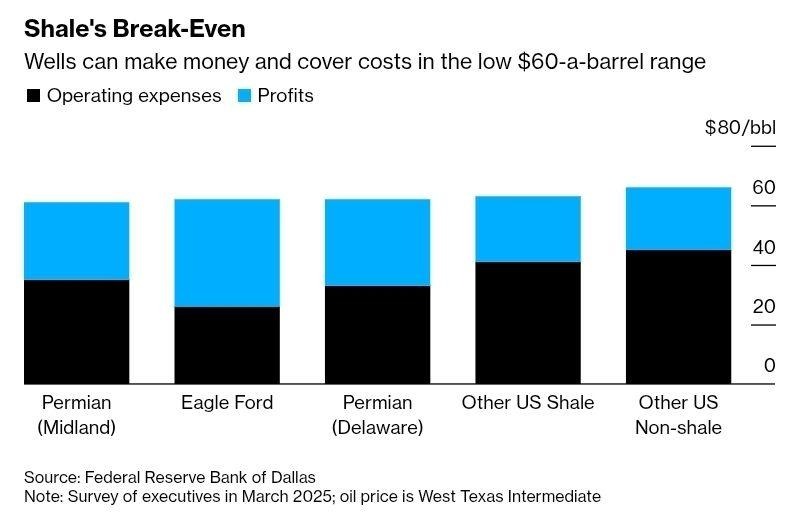

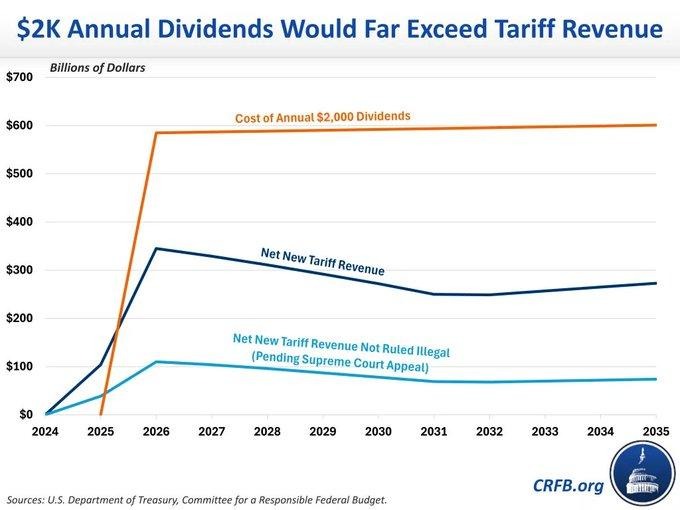

Chart(s) of the Week