Welcome to Dispatch Energy! Artificial intelligence is growing faster than the electricity system that powers it. The surge in data center construction is pressuring a grid built for slower, steadier demand, raising the risk that power scarcity, rather than engineering limits, will set the pace of AI progress. These strains will not remain abstract. They shape consumer costs, grid reliability, and the economic trade-offs we face as AI adoption accelerates.

AI in the Electrons

Data centers in the U.S. used 183 terrawatt-hours of electricity in 2024, roughly the same amount as the entire country of Malaysia. When Google’s engineers first paired transformers with specialized chips in 2017 to unleash artificial intelligence, they probably didn’t realize they were creating an electricity crisis. But the seeds of today’s challenges arising from data center energy use actually go back even further.

In 1993, a 30-year-old engineer founded a niche gaming chip company focused on 3D graphics. The technology that would later become the core of this enterprise, the graphics processing unit (GPU), performed many computation processes in parallel, an approach entirely different from the central processing unit (CPU) architectures that powered the early internet and later enabled search and cloud computing.

This engineer was Jensen Huang and the company was Nvidia. What began as a specialized graphics venture evolved, through the invention of the GPU in 1999 and the CUDA software development platform in 2006, into the computing backbone of modern artificial intelligence. When Google researchers introduced the transformer model in 2017, described in the now-famous “Attention Is All You Need” paper, and paired it with Google’s own tensor processing unit (TPU) chips, the pieces were in place. Nvidia’s hardware and Google’s model innovations collided in November 2022 with the public launch of large language models.

We have been living with AI—and a seemingly endless stream of new models and improved capabilities—ever since. We are still learning what these technologies will mean for work, learning, creativity, and even how we understand ourselves as humans. But one of AI’s most profound social and economic effects will be on energy.

The relationship between AI and electricity is not simple, but it is fundamental. GPUs perform far more computation than CPUs, which makes them well-suited for AI training and inference but also more electricity-intensive. AI workloads fall into two categories: the training of models, which requires immense datasets and billions of parameters, and inference, which uses the trained model to respond to queries. Estimated energy use per prompt ranges from 0.24 watt-hours (Wh) to 2.9 Wh, compared to about 0.3 Wh for a standard Google search. This means AI queries can use 10 times more energy, or even as much as 30 times more energy, depending on the model and hardware efficiency. For context, running a hair dryer uses 20 Wh per minute, and a refrigerator uses 3 Wh per minute.

Huang has long emphasized energy efficiency as a design priority. Advanced GPUs deliver dramatically more computation per watt than earlier generations. Nvidia’s 2024 Blackwell GPU is reported to be 25 times more energy efficient than the 2022 Hopper, an astonishing improvement in only two years. Data center operators pursue similar gains at the facility level. Power usage effectiveness (PUE), the ratio of total facility energy use to IT equipment energy use, captures how efficiently a data center turns electricity into computation. PUE is like a golf score: lower is better, with 1.0 as the theoretical minimum. Companies like Google use it to benchmark progress in both hardware and building-level efficiency.

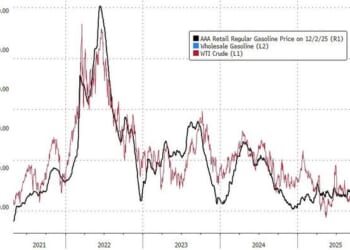

Yet per-unit efficiency, while vital for getting the most bang for the buck out of energy use, is not the same as total electricity consumption. Computation-level gains can coexist with system-wide load growth when demand for AI rises faster than efficiency improves. In 2024, U.S.data centers accounted for about 4.4 percent of national electricity consumption. Forecasts vary widely—some suggest this share will rise toaround 5.7 percent by 2030, while others estimate a range between roughly 6.7 and 12 percent. Data centers will consume an ever-larger share of a growing demand for electricity, increases not seen in 25 years.

The underlying economics is straightforward. When efficiency lowers the cost of computation, more computation becomes economically attractive. English economist William Stanley Jevons recognized this relationship in his 1865 book The Coal Question, observing that more efficient steam engines increased, rather than decreased, Britain’s coal consumption because they made new applications viable. Jevons worried that as steam engines became more energy efficient, the increased demand for them would then increase the demand for coal, perhaps so much so that coal would become expensive and constrain economic activity through the feedback effect on the cost of operating a steam engine.

This logic applies directly to AI. Data centers are the steam engines of the digital economy, and electricity is their coal. More AI compute entails more electricity consumption, and the pace of innovation in AI means that demand for computation is expanding rapidly. But unlike in Jevons’ time, when industrial energy demand unfolded over decades, today’s growth is compressed into a few years.

One fundamental challenge is the temporal mismatch between the speed of digital expansion and the much slower pace of electricity system development. A hyperscaler can design and construct a new data center in roughly 18 to 24 months. By contrast, building new generating capacity typically takes several years, and building high-voltage transmission lines routinely takes seven to 10 years or more, given permitting, routing, environmental review, and litigation. Even if institutional processes worked perfectly, the physical supply chain now imposes its own lag. Large power transformers have lead times of two to four years. Gas turbine delivery timelines have stretched toward seven years as global demand for firm generation increases. These supply chain bottlenecks mean that even well-planned projects cannot align easily with the fast cycle of data center deployment.

The result is a structural timing gap. The digital economy expands on a product-development clock, while power systems operate on an infrastructure and regulatory clock. When Huang describes AI as a power-limited industry, and when Google’s Sundar Pichai agrees and explores ideas as speculative as data centers in space, they are responding to this gap. OpenAI’s Sam Altman captured the sentiment succinctly at the Progress Conference when asked what would most accelerate compute availability: “Electrons.”

This rapid expansion amplifies a second problem: uncertainty.Forecasts of AI-driven electricity demand diverge sharply. The International Energy Agency projects global data center demand could roughly double by 2030. A Department of Energy-backedstudy from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory suggests U.S. data center load alone could nearly triple by 2028, with plausible outcomes ranging from about 74 to 132 gigawatts, essentially somewhere between “a lot” and “holy cow.” Deloitte estimates that U.S. AI-specific data center capacity could grow from 4 gigawatts in 2024 to 123 gigawatts by 2035. Studies by EPRI, McKinsey, and others reach different conclusions still. These discrepancies arise from differing assumptions about hardware efficiency, cooling systems, software optimization, workload distribution, and how quickly AI applications diffuse through the economy.

For electricity system planners, the size of the spread matters as much as the point estimates. Infrastructure decisions are capital-intensive, irreversible, and slow. Infrastructure investment planners operate under deep uncertainty, and uncertainty widens risk. Building large-scale infrastructure requires committing capital years before loads materialize. Overbuilding based on optimistic forecasts risks leaving utilities with underutilized assets whose costs flow through to ratepayers. Underbuilding risks shortages, congestion, and reliability challenges that raise costs for everyone and potentially constrain AI deployment. The challenge is not simply that demand is growing; it is that the future range of demand is wide at exactly the moment when investment decisions are most binding.

A fundamental economic principle underlies these observations: Scarcity shows up in your wallet or your wait time, and usually both. Innovators respond by reducing the demand for the scarce input or by increasing its effective supply. We are seeing both responses now. Google recently reported a 33-fold reduction in the median energy use per Gemini prompt compared to last year. GPU and TPU architectures continue to deliver more compute per watt. Data center designs, cooling techniques, and software models evolve to reduce the electricity required for a given level of performance. Innovation pushes the system toward greater efficiency, but it does not eliminate the underlying economic tension: Electricity remains the scarce input, and the institutions and supply chains that produce it operate on fundamentally slower timescales than the digital technologies they support.

The story of AI and electricity is ultimately a story about how fast innovation collides with the slower rhythms of physical infrastructure. Data centers can scale on an 18-month horizon; the grid that powers them requires years of planning, permitting, and construction. Efficiency gains will continue, and they will help. New models will be leaner, chips will extract more computation per watt, and data centers will push closer to the theoretical limits of power usage effectiveness.

But none of these innovations dissolve the fundamental scarcity of electricity or the institutional frictions that shape its supply. The economics of AI therefore extend well beyond GPUs and model architectures: They hinge on how societies manage uncertainty, allocate risk, and invest in long-lived assets under conditions of rapid technological change. If we want AI to realize its potential, power systems must evolve with equal ambition, by building flexibility, resilience, and adaptability into the very structure of our power infrastructure (all topics for further exploration in Dispatch Energy).

Holiday Giveaway: Grab your copy of Sword&Scales

PLF’s quarterly magazine Sword&Scales delivers one-of-a-kind historical narratives, high-stakes courtroom showdowns, and firsthand accounts of ordinary Americans standing up to government overreach and abuse. As an exclusive holiday offer, we’re giving away *100* copies of our Fall 2025 edition—shipping included—while supplies last. Claim your free copy today!

Note: Offer good through 12/31/2025. Some restrictions apply.

Policy Watch

- In late October, Secretary of Energy Chris Wright set off a flurry of activity with a Department of Energy Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking directing the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) to institute rulemaking to “ensure the timely and orderly interconnection of large loads to the transmission system.” Interconnection of generation resources to transmission grids can take up to seven years in some regions, although it varies across the country, and as more and larger data centers are built, interconnecting such large loads quickly will also pose a challenge. Across the country, with the exception of Texas, FERC is the regulator with jurisdiction to ensure that power systems in interstate commerce operate in a just, reasonable, and nondiscriminatory manner, so this directive orders the commission to develop rules to meet those regulatory requirements. Among other things, the DOE proposes standardized interconnection rules that mirror the standardized generator interconnection rules implemented in 2003. FERC received more than 175 public comments on the docket for this directive (including mine), and the hot topic in this proceeding is whether FERC-mandated standard load interconnection requirements violate the separation of jurisdiction between FERC over interstate commerce issues and the states over traditional public utility issues of delivery and service quality.

Innovation Spotlight

- Base Power Company, a Texas-based energy company, is flipping the traditional energy business model on its head. Instead of choosing between expensive backup generators (often $18,000-plus) or rolling the dice during Texas power outages, homeowners can pay just $695 upfront to get a whole-home battery system installed, as well as competitive electricity rates that are an average of 15 percent lower than typical bills. Here’s what makes it innovative: Base doesn’t make money by charging more for electricity. Instead, the company earns revenue by using the batteries to help balance the Texas power grid. When electricity demand spikes across the state, each battery can send power back to the grid. When the grid goes down, each battery can automatically switch to keep the lights on for up to 48 hours. It’s a win-win-win: Homeowners get affordable backup power and low electricity rates, Base earns income by providing grid services, and the Texas grid becomes more stable and resilient. More than 6,000 Texans have already signed up, essentially getting backup protection that would cost tens of thousands of dollars elsewhere for a fraction of the price—because they’re helping solve a bigger problem in the process. It’s a beautiful example of the combination of innovative hardware and software with markets, and how that combination creates value for buyers, sellers, and power systems.

- Researchers at Monash University in Australia have developed a new graphene-based supercapacitor that achieves battery-like energy storage while maintaining the lightning-fast charging speeds supercapacitors are known for. The key innovation involves restructuring carbon into what they call “multiscale reduced graphene oxide”—essentially creating curved, interconnected graphene networks with multiple size scales working together. Through a clever two-step rapid heating process, the team transforms ordinary graphite into this specialized architecture where ions can move exceptionally quickly through carefully designed pathways. When they apply a specific voltage during initial charging, the material opens up spaces between graphene layers that were previously inaccessible, tripling the energy storage capacity. The resulting devices achieved energy densities approaching conventional lead-acid batteries, and that can charge and discharge far faster than conventional batteries. This combination of battery-like energy storage with supercapacitor-like charging speed could transform applications from electric vehicles to grid stabilization, all while using abundant graphite as the raw material and processes that appear scalable for commercial production.

Further Reading

- Chevron has selected West Texas’ Permian Basin for its first natural gas power plant dedicated to serving AI data centers, with operations expected to begin in 2027. The facility will initially generate 2.5 gigawatts—roughly equivalent to two nuclear reactors—with potential expansion to 5 gigawatts. The plant will operate “behind-the-meter,” meaning it will bypass the regional transmission grid entirely and supply power directly to a co-located data center. Chevron is in exclusive negotiations with an unnamed data center operator and plans to make a final investment decision in early 2025. The project solves a unique problem in the Permian Basin: the region produces so much natural gas that it often overwhelms pipelines and has to be burned off (a practice called flaring). Rather than waste this stranded gas, Chevron can convert it directly into electricity for a customer willing to locate nearby. Chevron is not the first to apply this strategy; a pioneer in this use of otherwise-flared gas to power computation is Crusoe AI. To read more about the West Texas project—and Chevron’s efforts to meet booming AI energy demand—check out this article by E&E News.