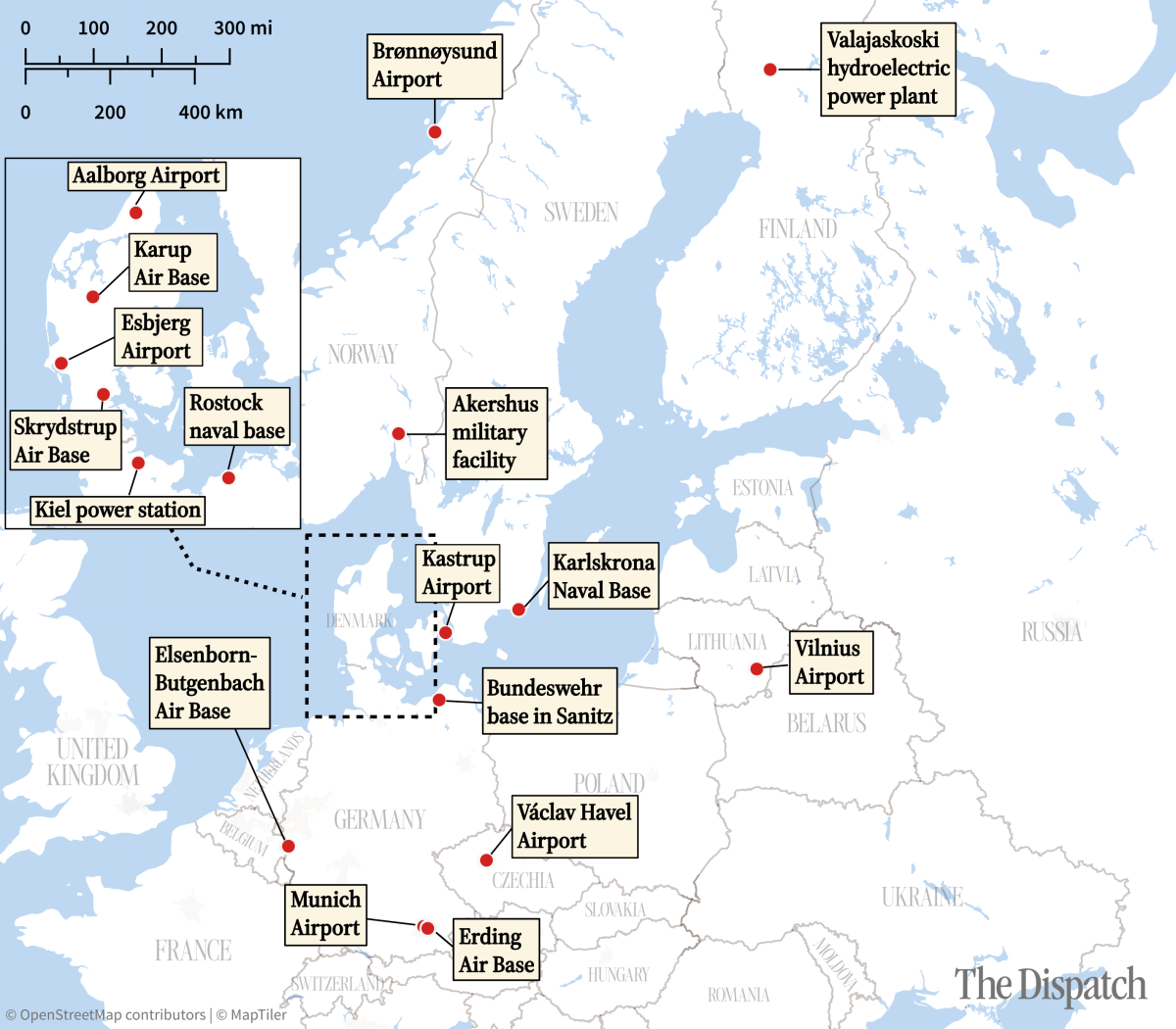

Fighting would presumably include repelling Russian drone incursions. During her speech, von der Leyen endorsed the idea of a “drone wall,” made up of radar systems and anti-aircraft weapons, that would intercept Russian drones and protect the whole continent. NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte called the idea “timely and necessary,” and at a September 30 meeting in Copenhagen, a number of European leaders threw their weight behind ramping up Europe’s drone defense capabilities.

But securing Europe’s massive border with Russia may be too tall an order. “I’m not sure that Europe is ready for this from a financial, technological, and organizational standpoint,” Kateryna Bondar, a fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies and a former adviser to the Ukrainian government, told TMD.

Bondar noted that the logistics of a true drone wall are staggering: hundreds of radar units and electronic jammers spread across at least the five countries—Norway, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland—that share a border with Russia, massive amounts of power generation required to maintain such a system, and a workforce to operate it. That’s before getting NATO, the EU, specific countries, and local governments to all agree on the specifics of the project.

Additionally, many of the drones likely used in some of Russia’s provocations are extremely difficult to intercept. Zachary Kallenborn, an expert on drone warfare who advises the U.S. government and defense companies, told TMD that the exact type of drone is crucial to answering the question of how to intercept it.

Medium- to large-sized drones powered by propellers, such as the Russian Geran (a copy of the Iranian Shahed drone), are relatively simple to detect and shoot down. Even when Russia launches mass attacks against Ukraine using hundreds of these types of drones, Ukrainian defenders are regularly able to intercept more than 90 percent of them. But reliably detecting and intercepting small drones, like the ones that caused airport shutdowns in Europe, is “not a feasible thing,” said Kallenborn.

These drones—often called First Person View (FPV) drones because they are piloted using a camera mounted on the drone’s body—are usually small enough to fit in a backpack and fly with quiet motors. The ones used in Europe were almost certainly unarmed, although small drones can be used to carry explosives.

“You can literally sit outside of the parliament building in Poland or wherever, and more or less pull it out of your backpack and throw it up in the air,” Kallenborn said. “You’re not blocking those.”

At least not with radar and jamming technology. This summer, the Ukrainian government announced a program that would pay citizens enrolled in local defense units up to $2,400 a month (a hefty sum in Ukraine) for shooting down Russian drones. Local teams are using hunting rifles, cars, and World War II-era machine guns to bring down Russian drones that threaten critical infrastructure like power stations and hospitals.

Another strategy is to harden buildings, using a tried-and-true technology: the humble net. Roads and houses near the Ukrainian front line are increasingly covered with shrouds of repurposed fishing nets, designed to tangle up smaller drones.

Low-tech methods such as these aim to address one of the most significant problems facing anti-drone efforts: It is far more expensive to shoot down a drone than to launch one. When NATO forces shot down Russian drones over Poland last month, they were using missiles that cost millions of dollars to destroy drones whose price tags were in the tens of thousands.

But simple countermeasures, while relatively easy to deploy quickly, are hardly a solution. They’re necessarily patchy and struggle to remain effective with larger or faster drones. More comprehensive measures—whether they be directed energy weapons (lasers) that are costly to build but dirt-cheap to fire, inexpensive anti-air missiles, or mass-produced interceptor drones—will take years to implement. Ukraine makes thousands of interceptor drones per month, but expanding production to other countries would take significant investment.

Some European leaders are already trying to temper expectations. “Drones and anti-drones are the priority,” French President Emmanuel Macron said last week. “But we have to be clear: There is no perfect wall for Europe. We’re speaking about a 3,000-kilometer border. Do you think it’s totally feasible? The answer is ‘no.’”

In what’s becoming an increasingly prominent pattern in European defense planning, countries located farther away from Russia are more hesitant to spend money on threats to the frontier. While leaders from Latvia and Lithuania last week pushed for a plan that could be implemented within a year, German Defense Minister Boris Pistorius has said that an anti-drone network won’t be completed “in the next three to four years.” Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni said earlier this year that “we must remember that the boundaries of the alliance are very large, so if we make the mistake of looking only to the side and forget, for example, that there is a southern flank, we risk not being decisive.” At the same meeting, Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez avoided discussing specific defense spending commitments. However, he did note that combating climate change is a “security aspect [that] will also be incorporated by the government of Spain in this debate.”

Financing and production are also major unanswered questions. The EU agreed to authorize 800 billion euros (U.S. $930 billion ) worth of defense spending in a landmark decision earlier this year, but only 150 billion of that (U.S. $174 billion) will come out of the bloc’s collective funds—the rest will have to come from individual members that have their own spending priorities and may not have extensive drone-building capabilities.

However, even if a drone wall is more a slogan than a realizable plan, there are political and diplomatic benefits for European leaders in endorsing it, Kallenborn noted. “It’s more about communicating a message to Russia that we don’t like that you’re doing this, we’re taking it seriously, and we’re prepared to respond,” while stopping short of military retaliation, he said. It also demonstrates to frightened European populations that their governments are taking action, Kallenborn argued. That sort of political strategy has precedent: In World War II, British anti-aircraft batteries were amassed in London to boost morale, while also attempting to shoot down German planes.

At the very least, Russia is displeased by the recent statements of European politicians. “As history has shown, erecting walls is always a bad thing,” Russian spokesman said Dmitry Peskov last week.

But the flurry of statements over the past week has yet to yield concrete spending commitments or a clear plan to revamp Europe’s defense production efforts, while still demonstrating clear differences between countries on priorities and strategy.

With those challenges in mind, Bondar was pessimistic about the drone wall’s prospects: “I think they’ll spend more time on discussions and being deeply concerned, rather than start actually building something.”