At the first public event of the Make America Healthy Again (MAHA) coalition in April, Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. urged governors to restrict food assistance for their constituents. Since then, many states have done so, earning praise from Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins, who has called them “pioneers in improving the health of our nation.”

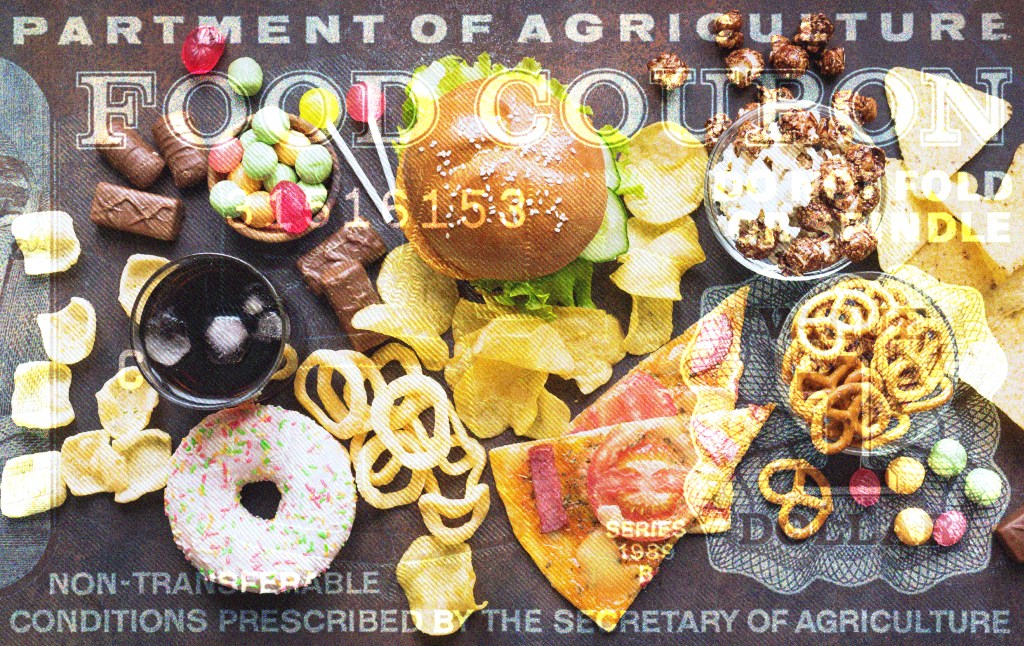

These restrictions have taken the form of amendments to the Supplementary Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), colloquially known as food stamps. The most significant change is that, beginning in January 2026, a dozen states will begin excluding certain items from the program’s definition of “food,” such as soda, energy drinks, and candy. Nebraska Gov. Jim Pillen described the motivation for introducing these restrictions. “There’s absolutely zero reason for taxpayers to be subsidizing purchases of soda and energy drinks,” he said. “SNAP is about helping families in need get healthy food into their diets, but there’s nothing nutritious about the junk we’re removing with today’s waiver.”

According to statistics cited by Kennedy, the United States has the highest rates of chronic disease in the world, despite spending more on health care than any other country “by a large margin.” The MAHA Report on childhood and chronic illness claims that “SNAP participants face worsening health outcomes compared to non-participants, exhibiting elevated disease risks: according to one study, they are twice as likely to develop heart disease, three times more likely to die from diabetes, and have higher rates of metabolic disorders.”

But the move to implement SNAP restrictions often turns a blind eye to the constraints present in the lives of food stamps recipients—and to the personal, financial, and bureaucratic costs involved in operating welfare programs. However well-intentioned, the MAHA movement often relies on false stereotypes and faulty assumptions about the agency of those living in poverty, as well as a shaky certainty about the economic effects these changes are likely to have. Comparing SNAP to other government aid programs like the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) is helpful in thinking these through.

SNAP and other similar programs are a valuable tool for helping individuals and families through difficult circumstances. Though many conservatives have a knee-jerk disdain for welfare, such assistance often puts struggling Americans in a better position to get jobs, address health issues, and, ultimately, increase household income. If conservatives really do favor “hand ups, not just handouts,” then they should be discerning about efforts to restrict SNAP.

Critics often compare SNAP unfavorably to WIC, which provides food assistance and nutritional guidance to pregnant and breastfeeding women, infants, and children up to the age of 5. Unlike SNAP—which until recently could be used to purchase almost any food or beverage item—WIC can be used only for a set list of eligible items and brands (E.g. Juicy Juice apple juice, Honey Nut Cheerios).

But choice is already constrained for families and individuals living near or below the poverty line. A frequent quip made to those struggling financially is to “just eat beans and rice.” Setting aside the nutritional concerns of a diet lacking fruits and vegetables, such advice ignores the psychological and emotional role that dining occupies in our lives. One of the major benefits of the way SNAP currently works is that it gives struggling Americans the dignity of allocating their own food budget in a way that suits the needs of their own families and seasons in life. MAHA officials are not wrong to draw attention to the chronic illness crisis in our country, nor are they incorrect in tying it—at least in part—to flaws in the American diet. But attempting to hold poor families accountable, rather than “big food” and “big ag,” seems more punitive than helpful.

At the very best, SNAP restrictions without improved consumer education and home economics training are a feeble solution to a significant problem. Many proponents of these restrictions decry the consumption habits of SNAP recipients from both a financial and a nutritional perspective, and yet the solution currently being pursued is only surface-deep. Studies indicate that only about 15 percent of Americans learn to cook in any formal setting, so if they don’t learn from family members, they are lacking this crucial skill. Researchers for a government-sponsored cooking program for low-income individuals reported that the program’s attendees would benefit from practices such as “shopping sales, looking for specials, comparison shopping among grocery stores, planning meals ahead of time, and buying bulk items.” These habits tend not to come intuitively; they need to be taught.

And yet, the “Big Beautiful Bill” has ended federal funding of the SNAP-Ed program, which has worked through land grant universities for decades to provide instruction on shopping, cooking, and nutrition to low-income Americans. The MAHA movement consistently suggests that more people should be cooking with fresh produce, whole foods, and nutritional savvy. As home economics programs declined across the nation, SNAP-Ed attempted to do just that: teaching at schools, farmers markets, and community-wide programs. As funding ceases for SNAP-Ed while restrictions roll out for food stamps recipients, it appears as though Republicans are more interested in punishing the poor and the nutritionally uneducated than in providing positive, long-term solutions.

The MAHA document on childhood chronic illness argues that WIC has likely been responsible for several positive health trends, and some want SNAP to operate on a similar model.

But WIC’s limitations make it much less attractive to grocers (who were the original impetus behind the food stamps program!), and as a result, far fewer stores accept it. For example, WIC benefits cannot be used at Aldi, one of the cheapest grocery chains in the U.S.—meaning, among other things, that these limitations could have unforeseen costs for the government.

Nor can WIC benefits typically be used at convenience stores like Dollar General—known, perhaps infamously, for its presence even in the most remote outposts of America. Data from the USDA indicate that convenience stores are by far the largest category of retailer accepting SNAP benefits (115,700 accept SNAP, while only 19,700 superstores do). While dollar stores create and exacerbate food deserts, which are characterized by distance from grocery stores and high poverty rates, the unfortunate reality is that they’re the only option for many Americans in 2025.

Even from a nutritional perspective, setting and implementing restrictions on SNAP is far from straightforward. It’s easy enough for a MAHA influencer or USDA official to refer to candy as “junk,” but it’s also a quick solution for a diabetic in a hypoglycemic episode and a festive treat for a mom filling Christmas stockings. Experimenting with expensive “mushroom coffees” might be a fun project if you have some extra change, but energy drinks and sodas can provide a more-or-less shelf-stable source of caffeine to exhausted workers with irregular shifts.

Calling on the government to make these judgments also invites an extended back-and-forth about nutritional guidelines. For example, the MAHA report on childhood and chronic illnesses praises the presence of whole milk and full-fat dairy products in a child’s diet. Yet, in 2014, WIC decided to cover only nonfat and 1 percent milk and nonfat yogurt for children over the age of 2. Do healthy fats increase obesity rates? Nutritionists can’t seem to agree. Who makes the final call?

Just as the state of Tennessee has taken steps toward restricting SNAP for its residents (though further consideration of its Healthy SNAP Act has been delayed until 2026), it has also introduced new limitations for WIC benefits. Beginning on May 1, the program ceased to cover the few organic products that had previously been eligible (except for fruit and vegetables purchased with a limited “cash value” monthly benefit). The MAHA movement has been dedicated to drawing attention to just how harmful the practices of conventional, non-organic agriculture can be, so why would it want to deny WIC participants access to organic options while claiming to champion their health? Low-income Americans are being urged toward better health one moment—and having their hands tied the next.

Conservatives should think seriously about their motivations for hovering over the food and beverage choices of struggling individuals and families. Given the astonishing rates of chronic illness in our nation, concern about using our tax dollars to compound the poor health of our poorest citizens makes sense. But this kind of oversight might end up costing more money than it saves, like when the state of Florida spent more money drug testing welfare recipients than it saved by kicking people off benefits.

SNAP restrictions provide a punchy headline for MAHA proponents, but they don’t necessarily improve the health of low-income Americans—and they might even prove harmful. Those in favor of SNAP crackdowns often severely overestimate the time, health, and culinary skills available to food-stamp recipients. I hope that MAHA continues to search for deeper solutions to our country’s chronic health crisis: removing harmful ingredients in our food products, advocating for restrictions around adolescents’ access to technology, and encouraging (instead of slashing) nutritional education programs at the state and county levels. Recognizing the limited agency of welfare recipients—and finding constructive ways to restore it—is a necessary part of making America healthy again.