Executive Summary

- One reason that elite professional positions are disproportionately held by Ivy and Ivy+ graduates is that Ivy and Ivy+ graduates in positions of power select people who share their educational backgrounds.

- U.S. Supreme Court justices who graduated from Ivy+ colleges are much more likely to hire clerks who graduated from Ivy+ colleges. U.S. Supreme Court justices who graduated from Ivy+ law schools are much more likely to hire clerks who graduated from Ivy+ law schools.

- U.S. Supreme Court justices who graduated from Ivy+ colleges or Ivy+ law schools hire clerks from a smaller set of colleges and law schools.

- Over the course of a 25-year career on the Court, a justice from a non-Ivy+ college will hire 17 more clerks who went to non-Ivy+ colleges. A justice from a non-Ivy law school will hire 22 more clerks who went to non-Ivy law schools.

- When the Commission on White House Fellowships has more members with Ivy+ degrees, it selects more fellows with Ivy+ degrees.

- Over the course of the White House Fellowship’s history, had the prevalence of Ivy+ commissioners been reduced from 40% to 20%, we could have expected 125 more White House Fellows without an Ivy+ degree.

Introduction

This is my second study on institutions of higher education and positions of American leadership. These reports explore the role that different types of colleges and universities play in preparing students for influential roles in society.

My overarching aim is to help policymakers, philanthropists, educators, journalists, and others better understand the contributions of different types of postsecondary schools. We should know where our governors, judges, business executives, and college presidents were educated. We should give credit where credit is due, of course. But we also need to know where to invest scarce resources. We should better understand which institutions have disproportionately educated our leaders: Are they close to home or far away? Public or private? Friendly or hostile to free speech and ideological diversity?

This research is also motivated by my desire to expand opportunity. Potential can be found in every corner of the nation—in affluent and low-income families, in rural and urban communities, in coastal and flyover states. We should aspire to provide all talented young people, regardless of their circumstances, pathways into leadership. That’s the promise of the American dream. But it is also in the national interest: we should make use of all the gifts that young people possess, and we want all Americans to see themselves in the nation’s leadership ranks. That builds national solidarity. We would be vulnerable to splintering if, for instance, our institutions chose leaders only from schools that privileged the superrich.

The Role of Selectors

In my previous report,[1] I examined the undergraduate and graduate schooling of each state’s leading private-sector attorneys and government leaders (governor, supreme court justices, attorney general, education chief, and legislative leaders). I found that more of these leaders graduated from public than private universities, in-state than out-of-state schools, and public flagships than Ivy+ institutions.[2] Moreover, in most of the nation, very few leaders attended faraway elite private schools (like the Ivies); in only a handful of states (e.g., California, Massachusetts, New York) are those credentials prominent. These findings contradict the common narrative—advanced by journalists and some studies—that America is largely led by the graduates of a few exclusive private schools.

This report considers these issues from a different angle. When studying those in leadership positions, we can, understandably, focus narrowly on the individuals who were chosen to lead. But that passive framing—those “who were chosen”—elides an important question: Who is doing the choosing? Ignoring that question encourages the assumption that credentials alone determine outcomes—that is, that those with certain educational backgrounds would be selected for these roles, regardless of the characteristics of the selectors.

That assumption is comforting, but few people believe that this is actually how the world works. Countless factors—some idiosyncratic, some predictable—can influence such decisions. Maybe the hiring manager—whose favorite uncle was a maintenance worker—selected the candidate who was friendly to a maintenance worker before the interview. Maybe several members of the search committee liked one candidate’s suit. One group of selectors might favor a candidate based on gender, race, or religion, while a different group of selectors might oppose the same candidate on those grounds.

As I noted in my first report, one particularly widespread influence among those who choose future leaders is affinity bias—the tendency for the selector, consciously or otherwise, to favor candidates who resemble the selector in some way. Perhaps they both grew up on Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, or both of their fathers were Marines, or they were both sociology majors.

Many have noted that those selected for prestigious roles—ranging from Rhodes Scholarships and MacArthur Fellowships to positions on the Harvard faculty, memberships in elite academic societies, top graduate programs, and jobs at leading firms—disproportionately tend to be graduates of the most selective private universities. The implication is that there is something special about those who graduated from these schools or that young people who aspire to leadership roles really should try to get admitted to these schools.

But, as I noted in my previous report, the selectors for those coveted positions are themselves disproportionately graduates of the same elite schools. Using the active, rather than the passive, voice changes our perspective. It’s no longer “John was selected as a Rhodes Scholar”; it’s “X selected John as a Rhodes Scholar.”

Now we must ask: Who, exactly, is X?

Recognizing Affinity Bias

There is reason to be concerned that the affinity bias of selectors is distorting America’s institutions and leadership class, as well as our perception of higher education. For example, if Ivy+ graduates lead many of today’s key institutions and then disproportionately hire or select Ivy+ graduates, our institutions will be perpetually overpopulated by Ivy+ products. That means that equally or more qualified young people from other schools are not being selected. It means that the category of “highly talented students with no interest in attending an Ivy+ school” will perpetually be underrepresented in leadership roles. It means that the political and cultural sensibilities of Ivy+ campuses will be overrepresented in our institutions. It means that our leadership class will be largely shaped by whatever formula that Ivy+ admissions offices are using.[3]

If we are committed to expanding opportunity, we should take seriously the possibility of significant affinity bias, which, in turn, should shape which reforms we pursue. For example, if we continue to think only of the supply side—candidates and their credentials—we may simply assume that Ivy+ graduates will dominate certain elite roles in public life into the future. As such, we will focus on the Ivy+ admissions process because the only way to change who gets the best professional opportunities is to change who gets admitted to Ivy+ schools.

But if we think of the demand side—those who choose—we may recognize a selector problem. The striking results that we see in America’s leadership ranks may be less a function of the candidates than of those who choose from among them. If that is the case, we will not care as much about Ivy+ admissions criteria. Instead, we’ll work to counteract affinity bias among the selectors for professional opportunities to prevent the disproportionate selection of Ivy+ graduates.

Isolating Affinity Bias

Graduates of elite private schools are often said to benefit from a “network effect”—the advantages that come from being connected to a long line of accomplished and well-connected alumni. These relationships can help new graduates navigate the professional world: meeting influential people, learning about job openings, or getting expert professional advice. In this report, I use the term “network effect” to mean the assistance that individuals receive from such connections to help them through the gauntlet leading to the hiring manager’s door.

Affinity bias is different. For example, if there are three finalists for a job and the hiring manager or search committee chooses the one with whom they share personal characteristics, that is “affinity bias.” If the network effect is having great coaches to help prepare for the big match, affinity bias is getting preferential treatment from the judges during the match itself.[4]

Measuring affinity bias is difficult. Most organizations do not publicly disclose the names of those charged with every selection decision—and virtually none report the names of every finalist who was not chosen—which makes it hard to assess the prevalence and extent of affinity bias.

Even if these problems could be solved, we would still need meaningful variation over time in the backgrounds of the selectors in order to draw conclusions. If the winner of a national academic prize has always been chosen by a graduate of Dartmouth or Brown, we won’t have any sense of what a non-Ivy+ selector would do. Similarly, if the search committee of a prestigious fellowship is always entirely composed of alumni of flagship public universities, we won’t have any sense of what that committee would do differently if it were instead made up entirely of Ivy+ graduates.

However, we can address these methodological issues by looking at two prominent and prestigious roles: White House Fellows (WHF) and law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS).

There is no greater professional honor for an early-career attorney than to be selected as a SCOTUS clerk. It is widely regarded as the path to the highest echelons of law and government. SCOTUS clerks have become governors, U.S. senators, U.S. attorneys, state supreme court justices, solicitors general, federal appeals court judges, SCOTUS justices, and more.

Similarly, the WHF program selects highly successful mid-career professionals from across the nation to serve for a year at the highest levels of the federal government (e.g., in the White House, as an aide to a cabinet secretary). WHF have become ambassadors, judges, governors, U.S. senators, cabinet secretaries, chairmen of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and more.

We have reliable lists of those who have been selected as SCOTUS clerks and WHF going back generations. We also know who selects SCOTUS clerks (SCOTUS justices) and WHF (the presidentially appointed Commission on White House Fellowships). As such, we can identify where selectees (clerks and fellows) were educated, where selectors (justices and commissioners) were educated, and the role that educational affinity bias plays. To be more specific, because there is variation among the education of both justices and commissioners, we can study whether the schooling of the selectors influences who is chosen as a clerk or WHF.[5]

Data and Method

The SCOTUS-clerk analysis begins by looking at all justices and clerks from 1980 through 2024. I attempted to identify the undergraduate and law-school education of all 1,636 clerks who served during this period.[6] I also identified the undergraduate and law-school education of the 24 justices who served during this period.

The WHF analysis includes the undergraduate and graduate education of all 454 individuals who have served as WHF commissioners from the program’s inception in 1965 until 2024. The analysis considers each year’s commissioners as a group (i.e., the commissioners of 1975 or the commissioners of 2009). Since the average commissioner served for about 3.5 years, there are roughly 1,600 commissioner entries.[7] The average number of commissioners per year is 26.7.[8] The analysis also includes the undergraduate and graduate education of all 892 WHF selected from 1965 until 2024. Fellows serve for one year. The average WHF class has 14.9 members.[9]

For the analysis of SCOTUS clerks, I group justices into categories based on education (Ivy+ or non-Ivy+, for both law school and undergraduate degree) and compare the schooling of the clerks selected by the different categories of justices.

With WHF, the analysis is different because the selection is done by a group of commissioners rather than by an individual. Therefore, I assess the collective educational background—using the same categories—of commissioners in a given year and of the fellows selected by the commission that same year.

If clerks and fellows were randomly selected from the college-educated population, we would expect their education backgrounds to be similar to that population. For example, more would have public than private undergraduate degrees; only about 1% would have an Ivy+ undergrad degree. Since slightly over 50% of the law-school population attend private law schools, we would expect a small majority of SCOTUS clerks to have a private-school law degree.

If graduates of elite private colleges or law schools are significantly more talented than those of other schools, we would expect those selected as SCOTUS clerks and WHF to disproportionately possess such degrees. But the rate of overrepresentation should be stable from year to year and unrelated to the profiles of the selectors. That advantage would be similar whether it was 1994, 2004, 2014, or 2024 and whether the selectors all graduated from Penn State or UPenn.

My hypothesis is that selectors possessing degrees from Ivy+ schools will favor candidates like themselves.[10] So while graduates of Ivy+ schools might enjoy a general advantage, they will enjoy a major additional advantage when higher percentages of justices and WHF commissioners possess those degrees.

SCOTUS: Clerks and Justices

While no research has directly examined educational affinity bias in SCOTUS clerkship selection, several studies have explored related questions. For instance, a valuable paper by law professors Tracey E. George, Albert H. Yoon, and Mitu Gulati found that the most important background characteristic for potential clerks is academic pedigree, rather than academic performance or other qualifications.[11] Where you attended school matters more than how you did in school.

Troublingly, the authors report that Harvard Law School graduates who graduate with the same honors (e.g., cum laude, magna cum laude) have very different chances of being chosen as SCOTUS clerks based on where they earned their undergraduate degrees: a top Harvard Law graduate who attended college at a less elite institution is significantly disadvantaged in the SCOTUS selection process years later, compared with an identically performing Harvard Law graduate who went to an elite college. In particular, having attended Harvard, Yale, or Princeton as an undergraduate conferred a very large advantage in the later SCOTUS clerkship process.[12]

As the study notes, the majority of both justices and clerks were educated at a few elite institutions. However, it does not address the question of interest here: whether differences among justices lead to differences among the clerks they hire.[13]

Descriptive Statistics of SCOTUS Justices and Clerks

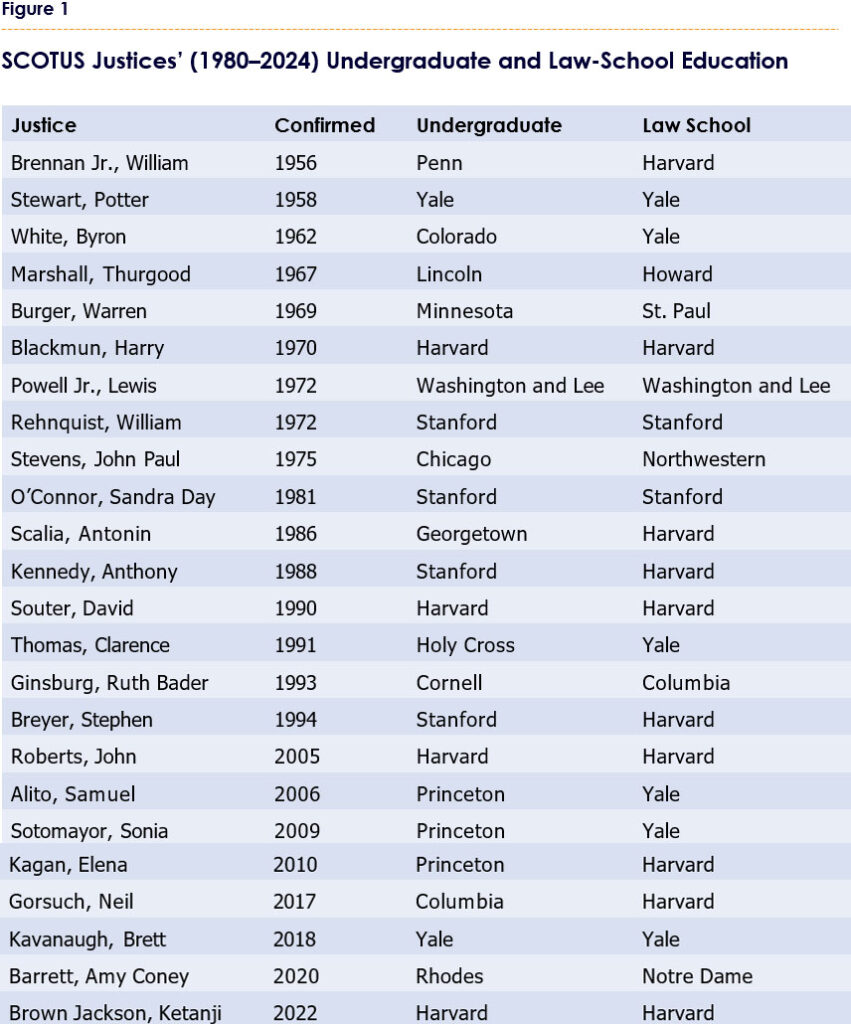

This section begins with basic statistics related to the education of justices and clerks. Since 1980, 24 justices have served on the nation’s highest court (Figure 1).

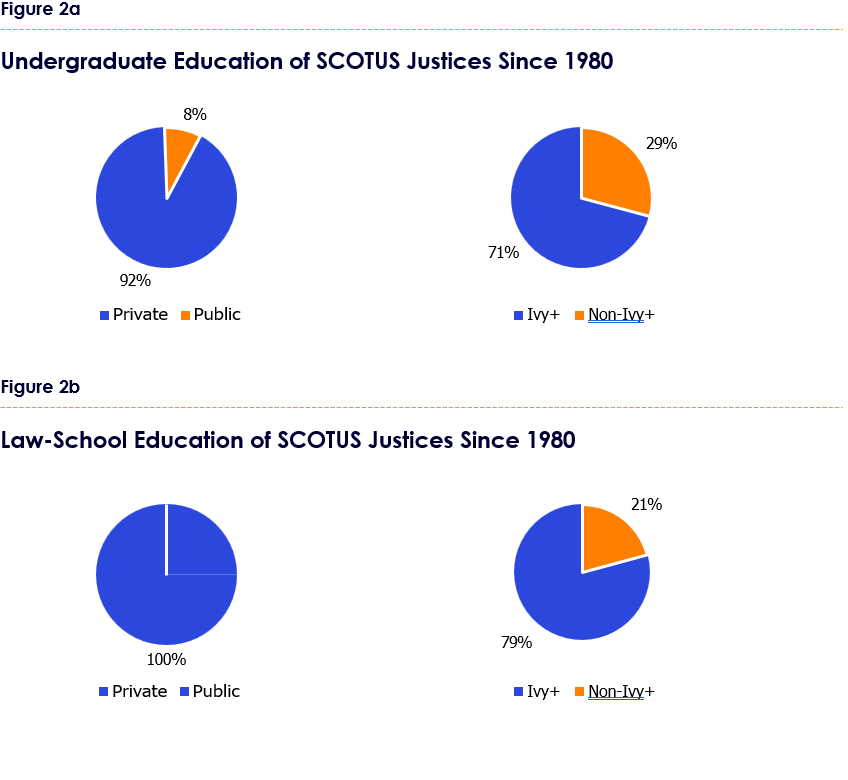

At the undergraduate level, only two of the 24 attended a public university (8%). By comparison, about 66% of today’s students in four-year colleges attend a public institution. Of the 24 justices, 17 attended an Ivy+ and 12 attended an Ivy (Figure 2a). Only 1% of today’s undergraduates attend an Ivy or Ivy+ college. The results are similar at the law-school level. Of the 24, none attended a public law school (almost half of today’s law students attend a public). Of the 24, 19 attended an Ivy+ and 17 attended an Ivy. By contrast, only 6% of today’s law students attend an Ivy+ (Figure 2b).

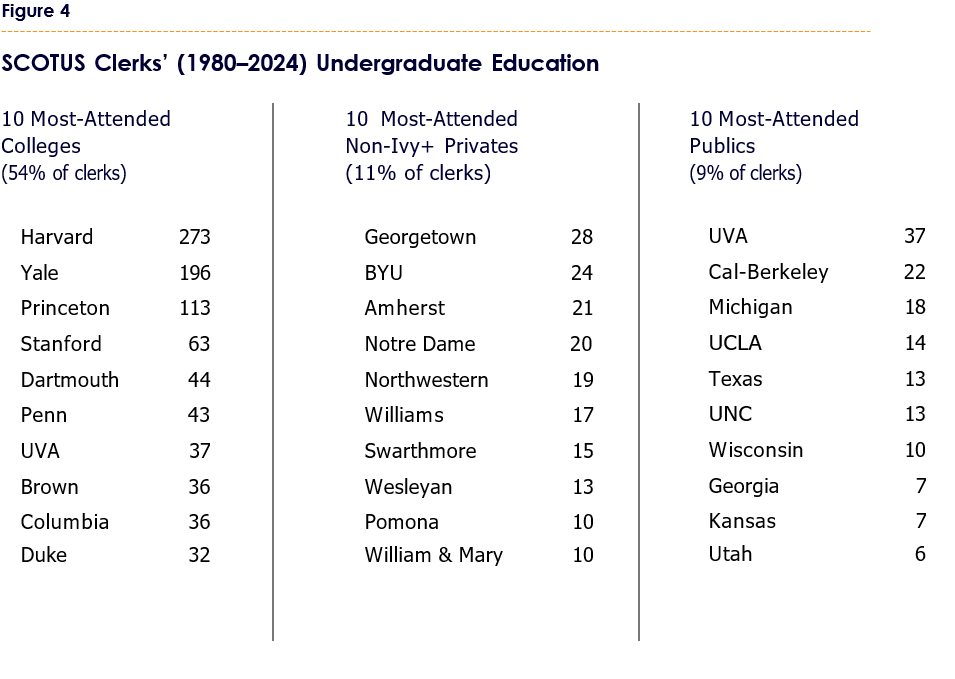

As noted above, I was able to identify the undergraduate institution of nearly all clerks (1,630 of 1,636). Only 18% (294) attended a public institution, while 81% (1,319) attended a private institution. About 1% (17) attended college outside the United States.[14] Remarkably, more than half (54%, 878) the clerks graduated from an Ivy+ college, and 47% (759) graduated from an Ivy (Figure 3).

The 1,630 clerks come from only 242 different undergraduate institutions, more than half (126) of which produced only one clerk in these 45 years; 54% of clerks come from just 10 schools, which, combined, enroll about 1% of America’s four-year college students. I.e., those schools educate one in 100 students yet produce more than one out of every two SCOTUS clerks (Figure 4).

Looking at just the 10 most frequently attended undergraduate institutions among SCOTUS clerks, two findings stand out. The first is the dominance of private, especially Ivy+, schools. Only one school—the University of Virginia (UVA)—is not an Ivy+. Seven of the top 10 are Ivies. The second finding is the dominance of just three schools: Harvard, Yale, and Princeton. Over the last 45 years, SCOTUS justices have collectively selected 36% of their clerks from these three schools, which educate just 0.14% of four-year college students. That is, fewer than 1 in 700 students go to Harvard, Yale, or Princeton for college; yet SCOTUS justices choose graduates of those schools for more than one out of three clerkships.

It is well known that SCOTUS clerkships disproportionately go to the graduates of a few law schools. But these findings go further and should be even more alarming to those who care about opportunity. We should be concerned that the highest ranks of the legal profession are shaped by decisions made about 17-year-olds by the admissions offices of three schools—especially since such schools give enormous preferential treatment to the children of the wealthiest, most connected families.[15]

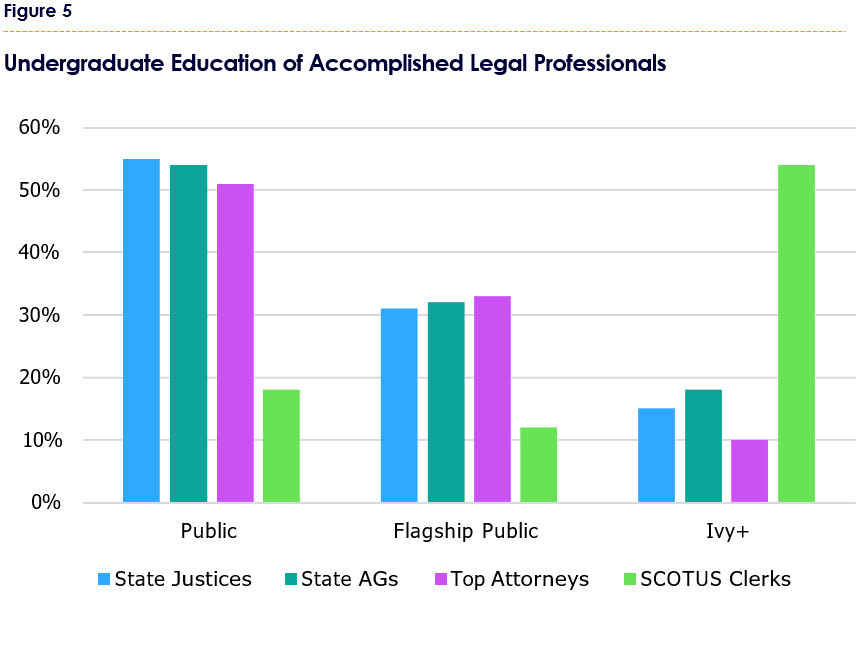

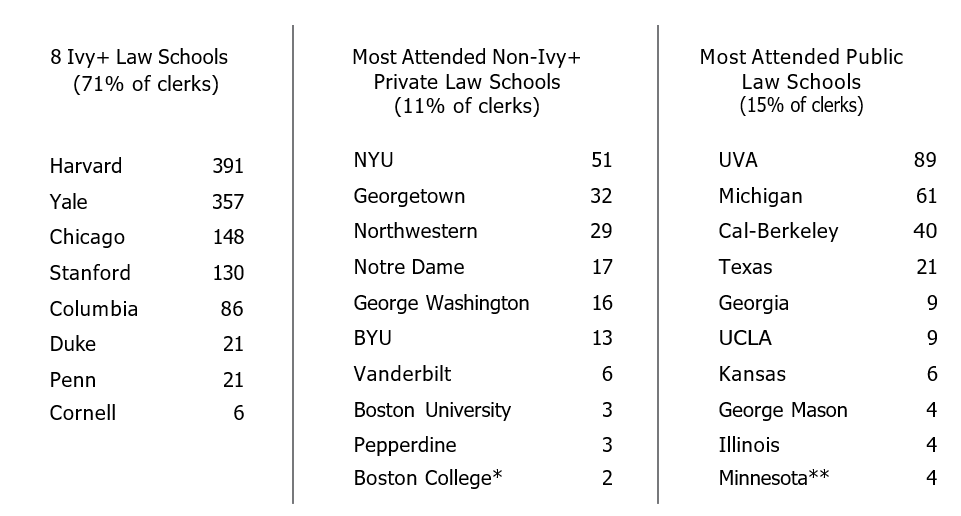

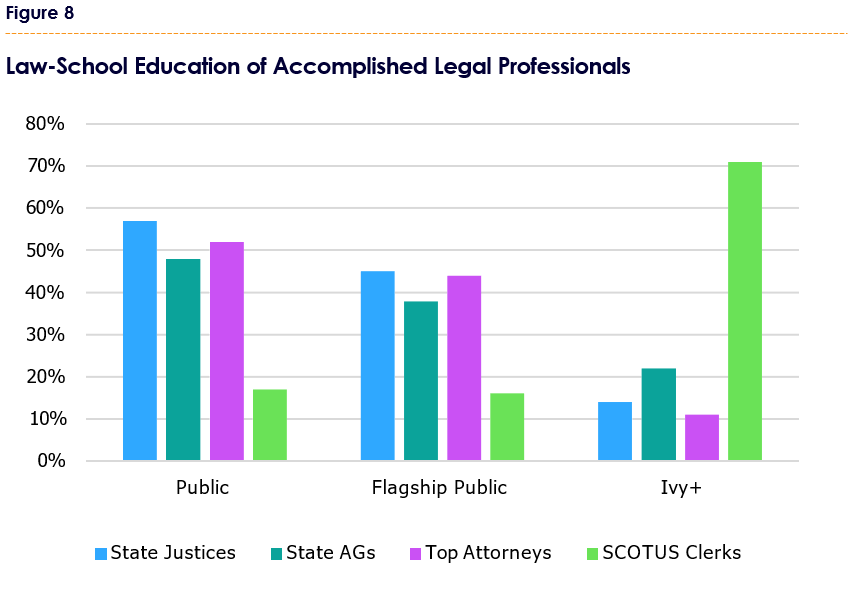

A comparison with the results of my previous report on this topic yields another striking finding: [16] several categories of the country’s most accomplished legal professionals were more likely to have graduated from public colleges than private colleges and from flagship publics than Ivy+ privates. Included in that study were all states’ supreme court justices and attorneys general, as well as the top attorneys in each state’s most prestigious law firms. Across all those groups, educational backgrounds were similar. In each category, more than half graduated from a public college, about a third from a flagship public, and fewer than one in five from an Ivy+. SCOTUS clerks are the outliers: very few attended a public college or the subset of flagship publics. Most attended an Ivy+ (Figure 5). Something is causing people with different educational backgrounds to end up in different elite legal circles.

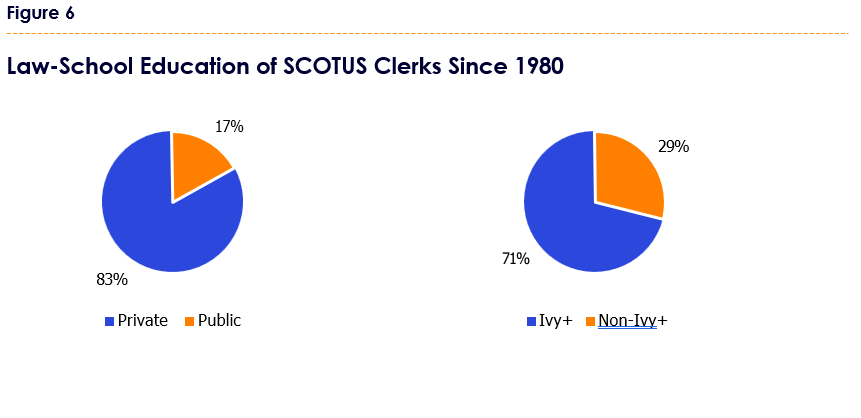

I next identified the law school of all clerks (1,636). The results show that the law-school pathway to a SCOTUS clerkship is even narrower than the college pathway. Only 17% (282) attended a public law school, lower than the 18% who attended a public college.[17] Fully 71% of clerks (1,160) have an Ivy+ law degree, and 53% (861) have an Ivy degree (Figure 6). These figures are even higher than the undergraduate figures.[18]

Only 65 law schools (out of about 200 nationwide) produced a SCOTUS clerk in the last 45 years. Of those 65, 21 have produced only one. One explanation is that four Ivy+ law schools produce 63% of clerks: Harvard, Yale, Chicago, and Stanford. The top 10 produced 85% (Figure 7). It may be tempting to believe that this is a recent phenomenon, but SCOTUS clerkships have historically gone disproportionately to the graduates of very few schools. According to Todd Peppers’s study Courtiers of the Marble Palace, from 1882 to 1910 only five law schools produced clerks. The next 30 years added only seven schools to the list.[19] My data show that in the last 45 years, the 10 most attended public law schools accounted for only 15% of clerks.

**UNC also had four

SCOTUS clerks’ law-school pedigree is very different from that of other highly accomplished legal professionals. About half the individuals in those other roles went to public law schools, and about 40% went to a flagship public law school. Only 10%–20% went to an Ivy+ law school. But few SCOTUS clerks went to public law schools, and nearly 75% went to an Ivy+ law school. SCOTUS clerks are roughly seven times more likely to have graduated from an Ivy+ law school as are the leaders of each state’s most prestigious law firms (Figure 8). Again, the question is: Why?

In practice, this means that a number of law schools are producing talented lawyers who are nonetheless ignored by SCOTUS justices. The starkest example is the University of Mississippi’s law school. Currently, nine of its graduates sit on state supreme courts. Only Harvard Law and Yale Law have more graduates as state justices. But only one Mississippi Law graduate has been a SCOTUS clerk since 1980. In that same time, Harvard Law and Yale Law have had 748 combined. Similarly, the law schools of the Universities of Montana, Nebraska, South Carolina, West Virginia, Wyoming, Kentucky, Oklahoma, and Arkansas educated 36 current state supreme court justices. But not a single SCOTUS clerk in the last 45 years came from any of those schools.

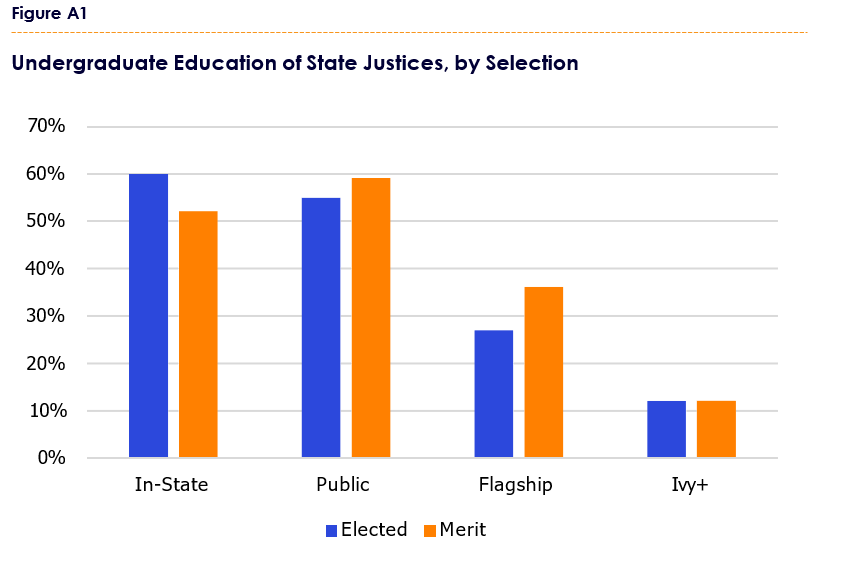

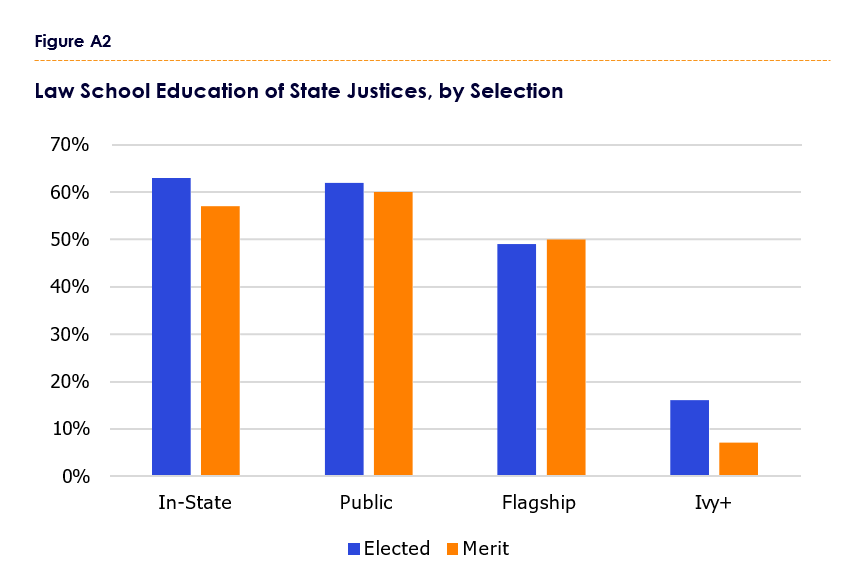

One explanation for the discrepancy could be that, in many states, supreme court justices are elected by voters, who may be less discerning of intellectual and legal ability, elevating instead those with electoral skills and those from local schools. This could be the reason that state supreme courts have so few Ivy+ grads. But the data tell a different story (see Appendix A). In only 21 states are justices elected (through a partisan or nonpartisan process).[20] In 21 states, justices are selected through a very different two-step “merit” or “assisted” process: The governor chooses from a list provided by an expert commission.[21] These two different processes produce nearly identical results in terms of the justices’ undergraduate and law-school backgrounds. In states that elect justices, 55% of justices attended public colleges; in states with a merit selection process, it’s 59%. In both sets of states, only 12% of justices went to an Ivy+ college.[22] Clearly, something other than the involvement of voters leads to so few state justices with Ivy+ degrees.

A second response could be, “But the students at Ivy+ law schools are simply much smarter than everyone else. SCOTUS justices want to pick the best, so they pick from Ivy+ schools.” It is true that the average LSAT score (the law-school entrance exam) is considerably higher at many of these elite institutions. At Harvard Law School, the median LSAT score is in the 98th percentile. By comparison, the median score at Ohio State’s law school is at the 88th percentile—still high, but not extraordinarily high, by comparison.

But presumably, justices do not select a law school’s median student. They choose from among the best. Because law schools also report the 75th percentile score of each class, we can at least compare the top-scoring quartile of each school’s entering class. Across the eight Ivy+ law schools, the average 75th percentile is just below 175, meaning that top-quartile students score in approximately the top 1% of all LSAT takers. At the eight non-Ivy+ law schools with the highest-scoring top quartile, the average 75th percentile score is remarkably similar: 173, or in the top 2% of scores.[23] And, of course, that means that many of those students are in the top 1%. That is, schools other than the Ivy+ have some of the nation’s most promising future attorneys. In fact, at seven public law schools, the top quartile of incoming students score in the top 5% of all LSAT takers.[24] Other public schools, including Alabama, Minnesota, North Carolina, Ohio State, and Texas A&M, have a top quartile scoring in the top 8%.

One reason public law schools often have a measurably lower mean LSAT score is that they enroll a higher number of relatively lower-scoring students (as indicated by their 25th percentile score), which depresses the median. But these schools still enroll significant numbers of very high-performing students. For example, the University of Texas (Austin) law school has a first-year class of about 280 students, and its top quartile LSAT score is 172. That means that about 70 of its students each year score at least in the top 2% of LSAT takers nationwide. This evidence suggests that hundreds of students at non-Ivy+ law schools have LSAT scores among the highest in the country. Presumably many, if not most, of these students did exceedingly well in their college coursework and then excelled in law school. And we know that graduates of non-Ivy+ law schools have gone on to be leaders in many public- and private-sector arenas. We should not assume that justices who want to choose the best clerks need to rely on Ivy+ schools. So again, we must ask: When there is great talent at other schools, why do SCOTUS justices focus on the graduates of just a handful of elite private schools?

Linking SCOTUS Justices and Clerks

Are Ivy+ schools equally dominant in clerkships for all justices? If all justices believe that the most capable clerks come from the same few elite schools, we would expect this to be the case. Alternatively, justices with Ivy and Ivy+ degrees might hire more clerks with Ivy and Ivy+ degrees, while justices with degrees from other institutions more often recognize that talent can be found outside Ivy and Ivy+ schools. We have hints that this might be the case.

Justice Thomas—who went to a non-Ivy school as an undergraduate—famously said that he looks for clerks from non-Ivy schools. “My new bias, which I now embrace, is that I don’t eliminate the Ivies in hiring, but I intentionally prefer kids from regular backgrounds and regular students.”[25] He told Congress, after serving on the Court for nearly a decade: “I tend to look beyond the Ivies on a fairly regular basis”[26]—unlike his colleagues. Thomas warned incoming clerks that this approach could come at a cost, since others viewed his clerks from less elite schools as “third-tier trash.”[27]

It has also been reported that Justice Barrett—who attended non-Ivy schools for undergraduate and law school—has been selecting clerks from the non-Ivy Notre Dame.[28] Chief Justice Rehnquist, who went to college and law school and worked in the West, was aware of justices’ proclivity to select clerks from elite East Coast schools.[29] In his book on the Court, he wrote that during his SCOTUS clerkship year, he was one of only two clerks educated west of the Mississippi, the others having been schooled by the usual suspects—Harvard, Yale, Columbia, and Penn.[30]

Rehnquist offered another hint along the same lines during an interview. He believed that the very best students at law schools were “fungible”—essentially saying that equally talented students are found at the top of most of these institutions. The only difference, he believed, was that the most elite law schools have more of the top-flight students.[31] Justice Souter, during congressional testimony in 1999, seemed to disagree with this view, saying of clerk candidates, “Nobody can seriously be considered who has not come to the very top of the law school classes in the most demanding law schools.” But later in that hearing, he agreed with Rehnquist’s assessment—but with a major caveat. He considered it risky to hire from outside the most elite schools because he had less experience with those institutions and their professors. Souter would not feel comfortable hiring from “outside the well-trodden paths” absent absolute certainty in the quality of references: “I wouldn’t dare to.” Perhaps justices with degrees from non-Ivy schools (like Barrett, Thomas, and Rehnquist) will hire clerks different from those of justices like Souter (Harvard undergrad, Harvard Law).

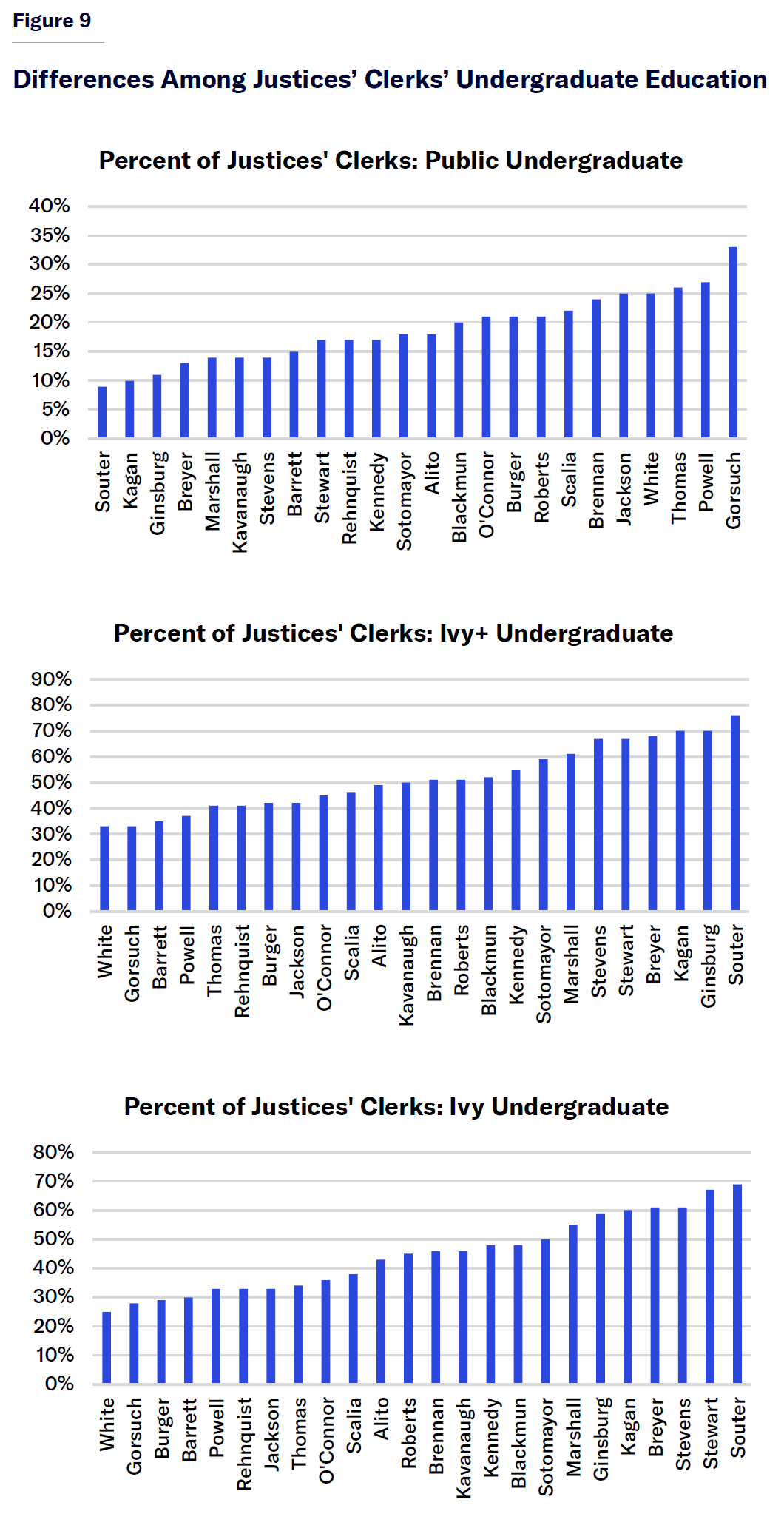

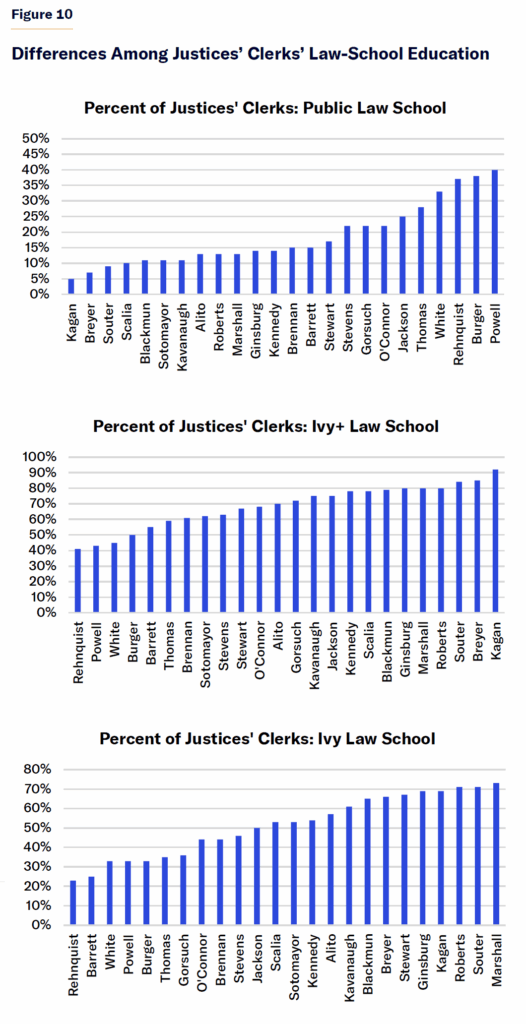

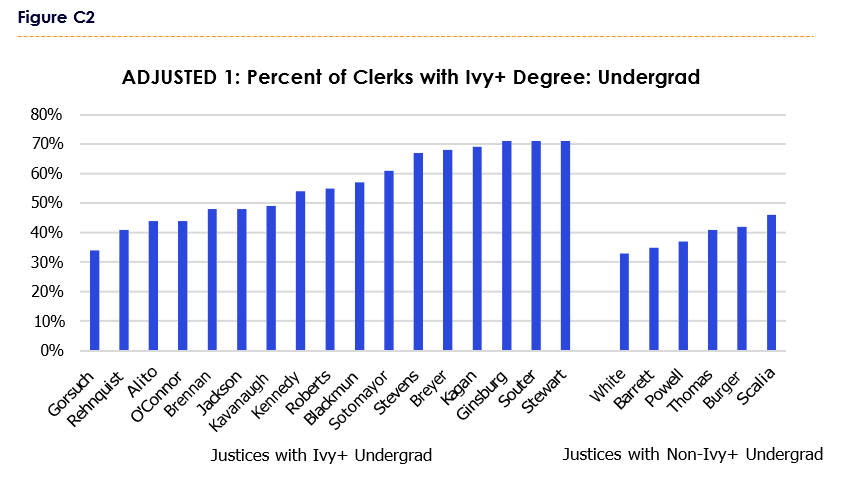

These anecdotes are backed up by the analysis conducted for this report, which shows that justices differ significantly when it comes to the educational backgrounds of the clerks they choose (Figure 9). In examining this question, I primarily use three categories: public, Ivy+, and Ivy. In my previous study, I also included “flagship publics” as a subcategory, but it does not make sense here to further divide the public category because only two justices went to a public college, and none went to a public law school; and few of their clerks went to a public college (18%) or public law school (17%).

Justices differ significantly in what portion of their clerks have undergraduate degrees from public colleges, with a 24-percentage-point gap between the bottom and top justice. There is an even bigger difference, 43 percentage points, between the justice most likely to hire clerks with Ivy+ undergraduate degrees (Justice Souter) and the least likely (Justice White). Fewer than one in three of Justice White’s clerks went to an Ivy+ college, compared with more than three in four of Justice Souter’s clerks. The difference for Ivy undergraduate degrees is slightly bigger: 44 percentage points—again with White and Souter serving as bookends.

We see the same wide variation in justices’ law-school preferences (Figure 10). For public law schools, the difference between the bottom and top justice is 35 percentage points. Only 5% of clerks selected by Justice Kagan went to a public law school, compared with two in five for Justice Powell. The variation is even wider when it comes to Ivy+ and Ivy law schools. Only 41% of Justice Rehnquist’s clerks graduated from an Ivy+ law school; 92% of Justice Kagan’s did. The Ivy-law school gap is 50 percentage points.

My hypothesis is that the variation in justices’ clerk selections is at least partially a result of the justices’ schooling. I suspect that Ivy+ justices choose clerks who share their educational backgrounds. Because so few of the justices since 1980 were educated in public institutions, this section focuses on Ivy+ (and Ivy) degrees. All justices since 1980 are included in the following analysis, apart from Justice Thurgood Marshall, who was educated during the era of racial segregation—meaning that many public and elite private schools denied admission to students of color. As such, it is difficult to fairly label the college and law school that he attended using the categories established.[32]

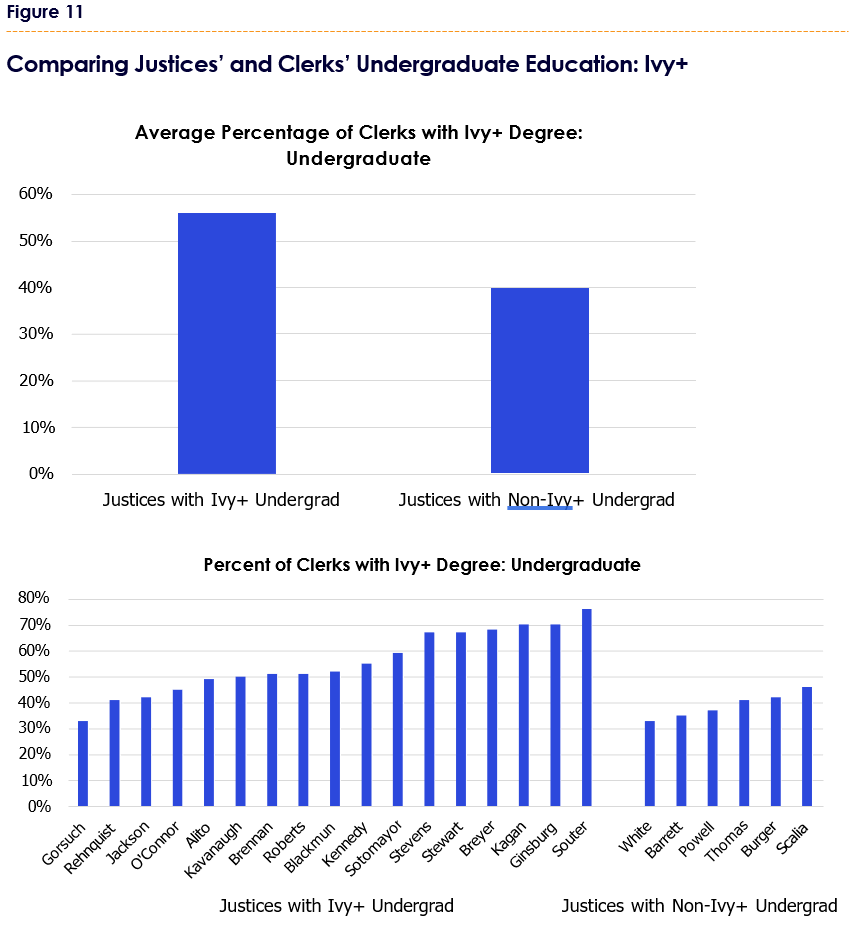

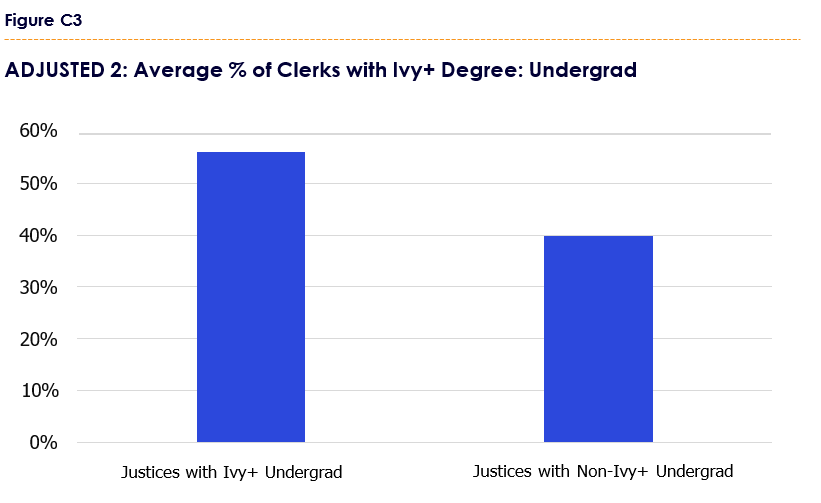

First, I compare the undergraduate backgrounds of clerks chosen by justices with an Ivy+ college degree with the undergraduate backgrounds of clerks chosen by justices without an Ivy+ college degree (Figure 11). I find that justices who went to Ivy+ colleges are much more likely (nearly 50%) to choose clerks who went to Ivy+ colleges. Justices who went to an Ivy+ college select 56% of their clerks from Ivy+ colleges; justices who went to other colleges select Ivy+ graduates as clerks only 39% of the time. This difference is highly statistically significant (p=.002). Six justices with Ivy+ undergraduate degrees selected at least two-thirds of their clerks from Ivy+ colleges.[33] In addition, justices with Ivy+ undergraduate degrees choose fewer clerks from public colleges and more from Ivy colleges than do justices from non-Ivy+ colleges.[34]

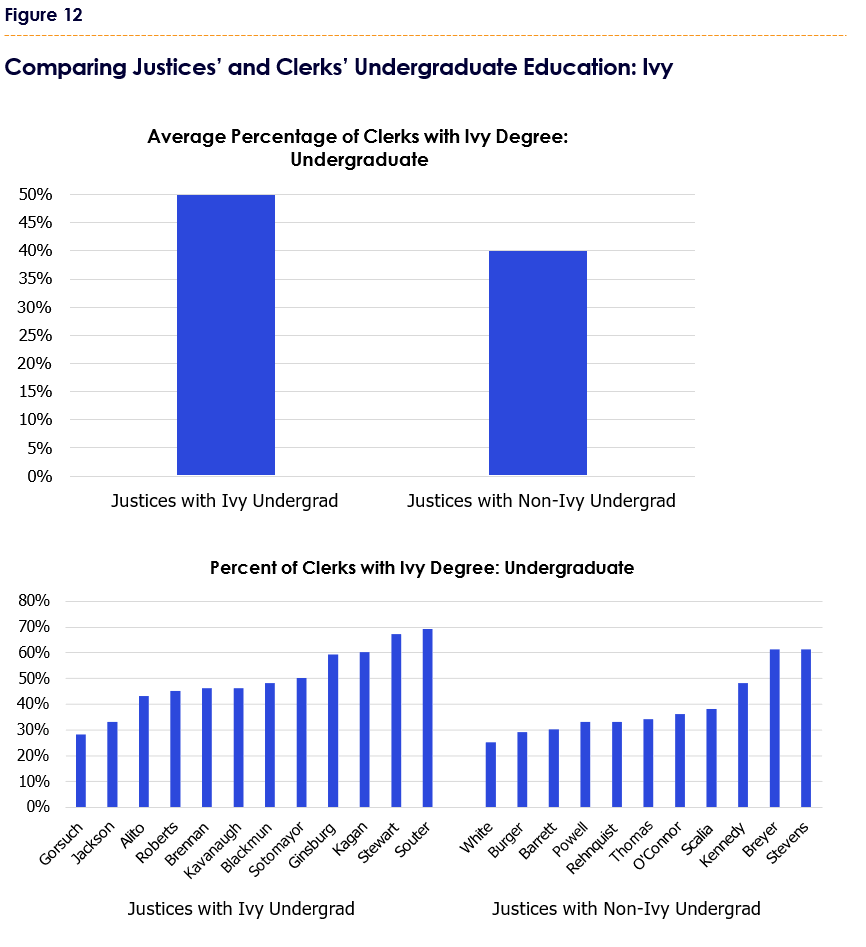

This finding is stable over time. Justices who graduated from Ivy+ colleges are about as likely today to choose Ivy+ graduates as clerks as similar justices did in the past. Justices who graduated from non-Ivy+ colleges have become slightly less likely to choose Ivy+ graduates as clerks (Appendix B).Figure 12 shows the results of analyzing the smaller category of Ivy colleges (instead of Ivy+ colleges, i.e., removing Chicago, Duke, MIT, and Stanford). Removing these four schools excludes 119 clerks. Even more important, five justices attended one of the non-Ivy Ivy+ colleges.[35] Are justices who graduated from Ivy colleges more likely to choose clerks who went to Ivy colleges? Yes, by 11 percentage points (p=.03).[36]

Given the findings from George, Yoon, and Gulati discussed earlier—that an undergraduate degree from Harvard, Yale, or Princeton conferred a major advantage in the later clerkship competition—I tested whether justices with Ivy degrees choose more clerks with undergraduate degrees from those schools. As we have noted, over 33% of all clerks attended one of these schools. But is this driven by justices who went to Ivy colleges? Yes. Ivy-grad justices choose, on average, 40% more Harvard, Princeton, and Yale graduates than justices who did not go to an Ivy college (p=.016).

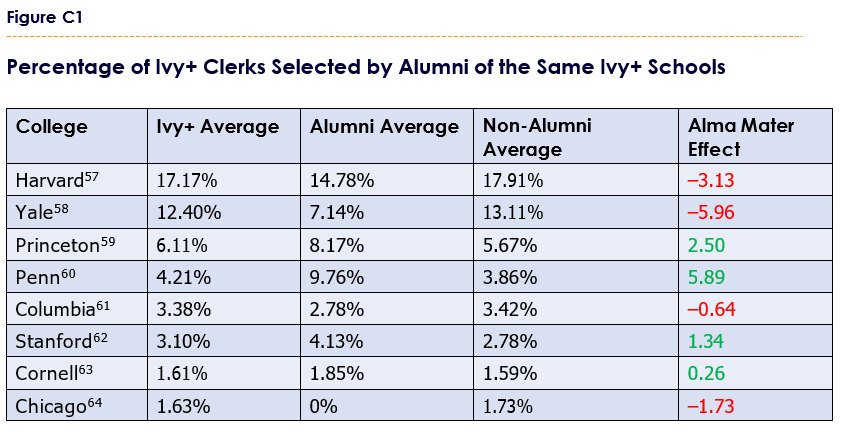

Finally, I tested whether these results could be attributed to an “alma-mater effect” instead of a more general Ivy+ affinity bias. If justices hired predominantly from the colleges they attended, these data would make it appear that Ivy+ justices were biased in favor of Ivy+ graduates. Appendix C, however, shows that these results are not a consequence of an alma-mater effect. In fact, it is surprising how little of an advantage justices give to applicants who went to their colleges. The Ivy+ affinity-bias finding holds.

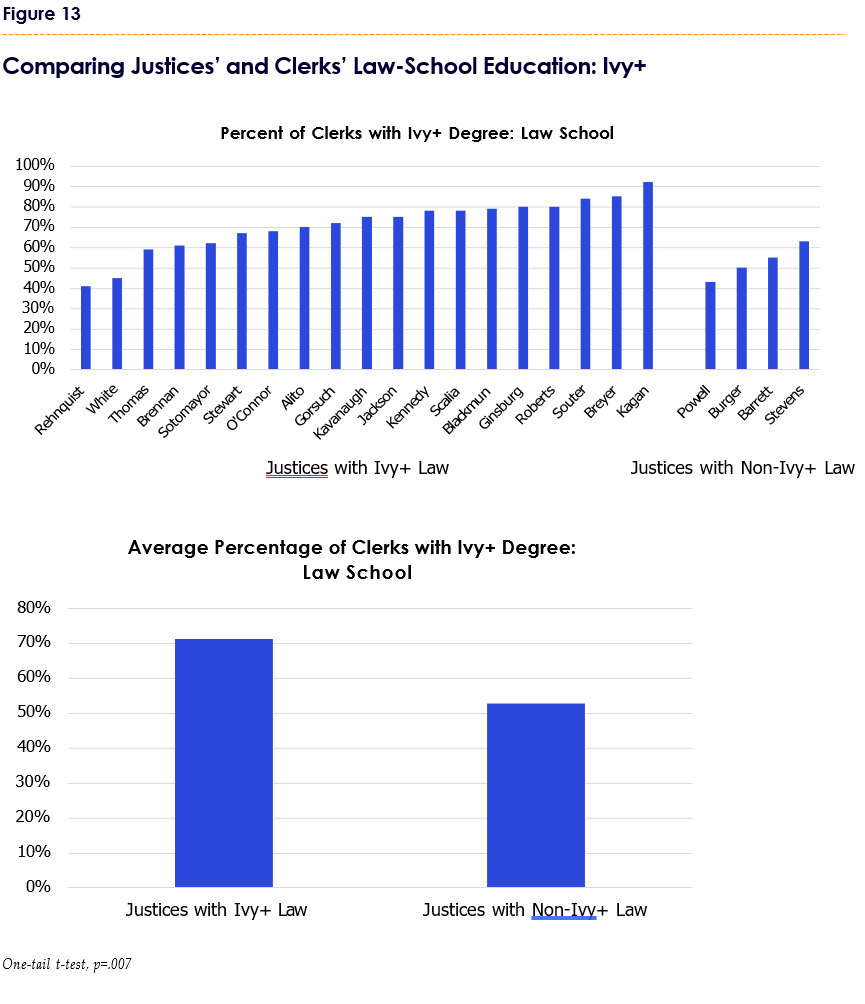

Now I turn to law school. As discussed, enormous variation exists among the justices when it comes to the law-school education of their clerks. Some justices hire a significant number of public law-school graduates while others hire astonishingly few. Some justices hire almost exclusively from Ivy+ law schools while others hire from a much wider array of institutions. Are these differences related to the schooling of the justices themselves? Yes.

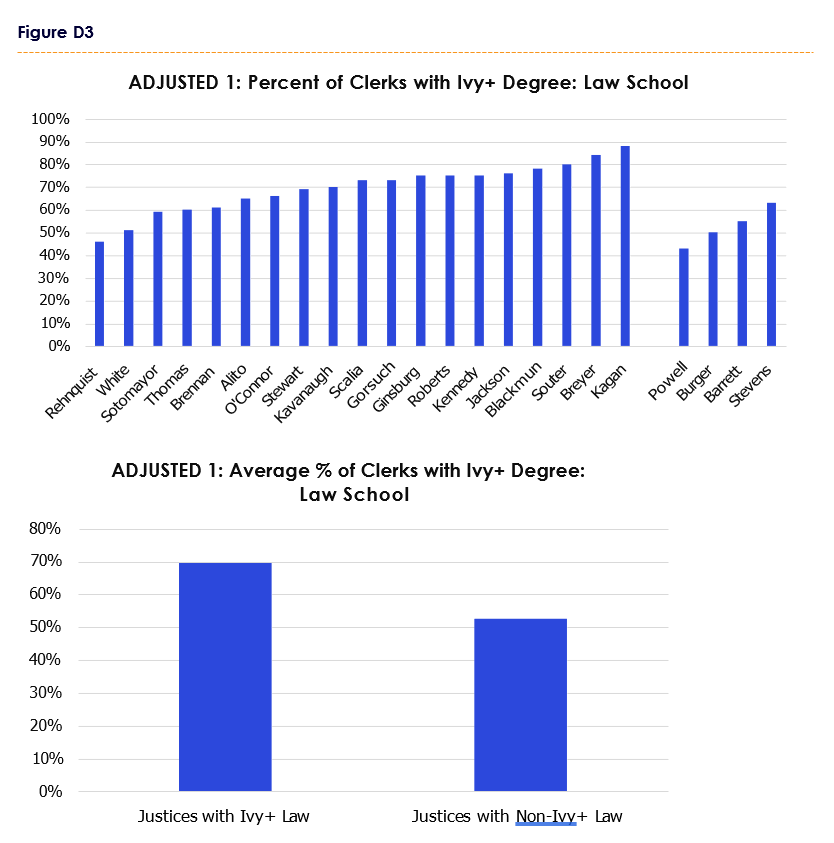

As above, I begin by comparing the clerks of justices with and without Ivy+ law degrees (Figure 13). Justices who graduated from an Ivy+ law school are much more likely to choose clerks with Ivy+ law degrees. The difference is 18 percentage points (71% vs. 53%) and highly statistically significant (p=.007). Also, justices from Ivy+ law schools are much less likely to choose clerks from public law schools than are justices from other law schools (17% vs. 29%, p=.01). And justices from Ivy+ law schools are much more likely to choose clerks from Ivy law schools than are justices from other law schools (54% vs. 34%, p=.009).

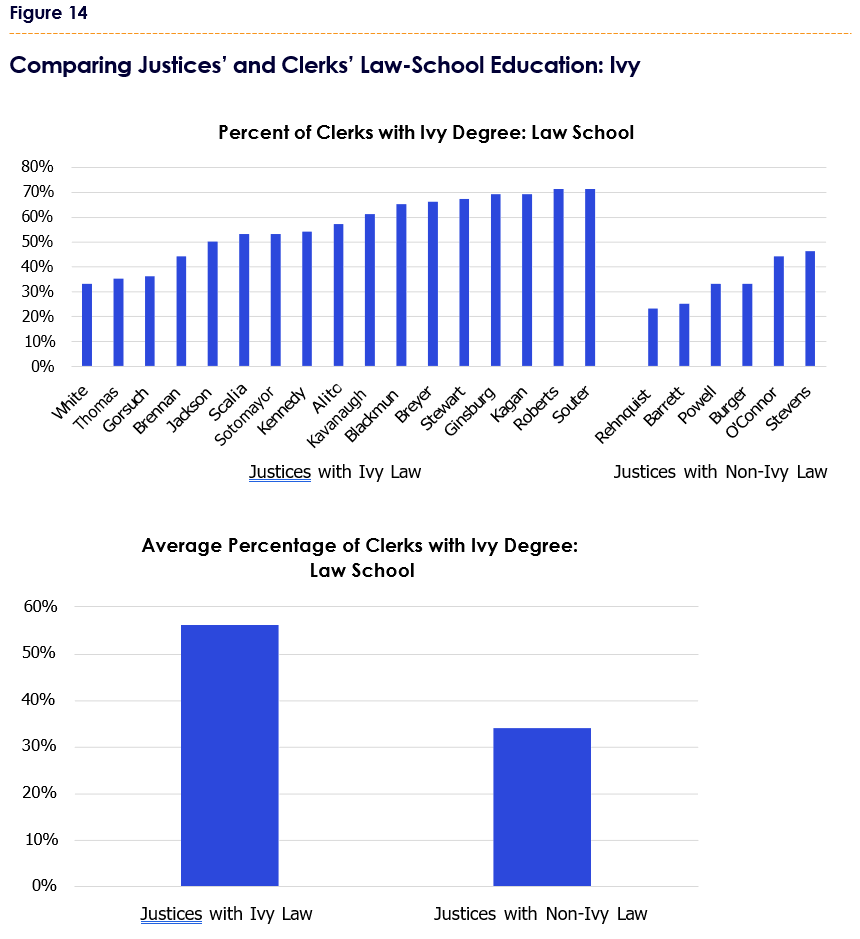

As above, I also tested whether the same effects are found when analyzing the smaller category of Ivy law schools (instead of Ivy+ law schools). Doing so excludes 299 clerks and two justices who attended one of the three non-Ivy Ivy+ law schools.[37] Are justices from Ivy law schools more likely to choose clerks from Ivy law schools? Yes—and by a larger margin than found in any previous analysis (Figure 14). Justices from non-Ivy law schools choose only 34% of their clerks from Ivy law schools. Justices from Ivy law schools choose 56% of their clerks from Ivy law schools (p=.0005). Justices from Ivy law schools also select far fewer public law graduates (15% vs. 29%, p=.001) and far more Ivy+ law graduates (73% vs. 53%, p=.0007).[38]

As with undergraduate education, I tested whether these law-school results could be attributed to an alma-mater effect. They cannot. Ivy+ justices hire disproportionately from the Ivy+ law schools broadly; in many cases, an Ivy+ justice’s top law school for selections is not his/her alma mater. The results are robust, holding after several adjustments (Appendix D).

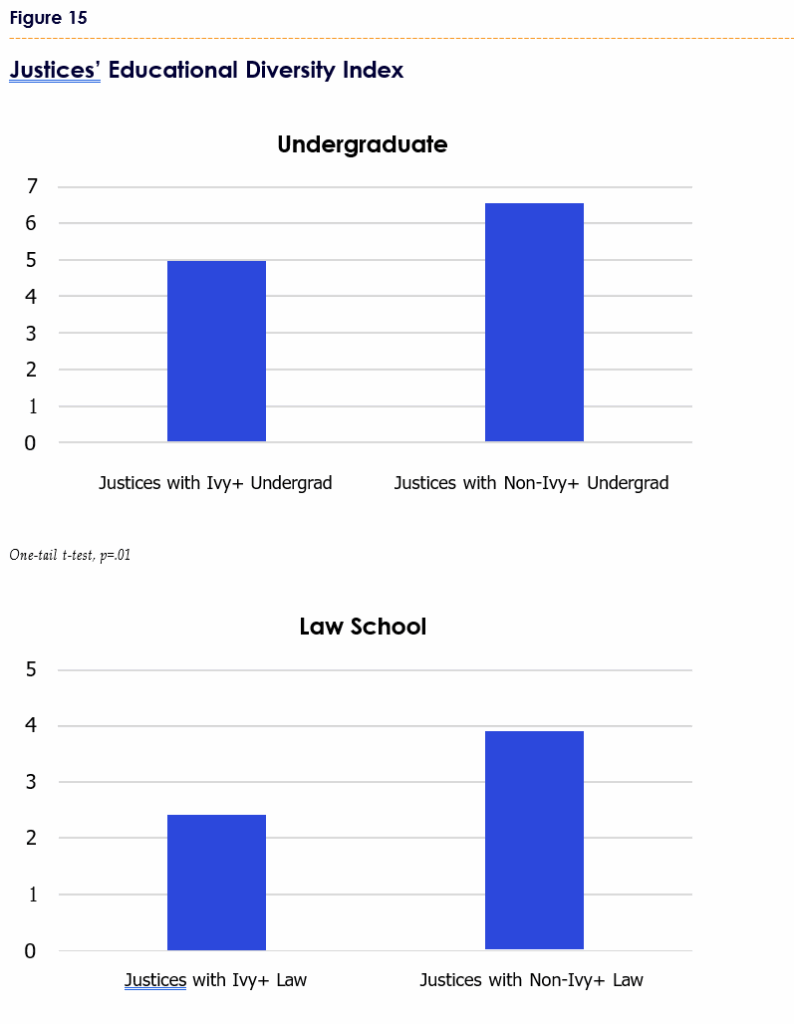

Last, I tested whether justices from Ivy+ colleges and law schools choose clerks from a smaller number of schools. Since this report is ultimately about opportunity, my interest here is in whether an Ivy+ education narrows a justice’s sense of where talent can be found. It may be that, as we have found, justices with an Ivy+ education choose more Ivy+ grads as clerks while still recognizing the wide distribution of talent and selecting their remaining clerks from a wide range of schools. My hypothesis, however, is that an Ivy+-educated justice will consider graduates of fewer schools to be worthy of consideration. And that, sadly, is what I found. I created an “educational diversity index” to assess from how many schools each justice hires (Figure 15). Because my range is limited to 1980–2024, some justices hired more than 100 clerks in this period, while others hired very few.[39] Thus, the index uses each justice’s total number of clerks as the denominator and the number of schools hired from as the numerator. I multiply that fraction by 10, so that the index answers the question, “On average, how many schools produce every 10 clerks hired by this justice?”[40]

Justices with Ivy+ undergraduate degrees hire from a smaller number of colleges than other justices (4.8 vs. 6.6, p=.01). Justices with Ivy+ law degrees also pull from a smaller number of law schools than other justices (2.4 vs. 3.9, p=.02). To be more concrete, Justice Ginsburg (Cornell) has the lowest undergraduate diversity index (3.1), while Chief Justice Burger (Minnesota) has the highest (8.3). Burger’s universe of selection schools is 2.7 times larger than Ginsburg’s. Justices Souter and Scalia (both Harvard Law) have the lowest law-school diversity index (1.2), while Justice Powell (Washington & Lee) has the highest (4.7). On average, Powell was willing to select from a set of law schools four times larger than those of Scalia and Souter.

It is possible, however, that the variation in justices’ tenures on the Court could skew these results. If two justices both selected clerks from 20 schools but one justice served twice as long as the other, the longer-serving justice would have a lower score. In Appendix E, I use a different approach to answering the question, which yields the same result: even when taking time on the Court into account, Ivy justices hire from a smaller set of schools.

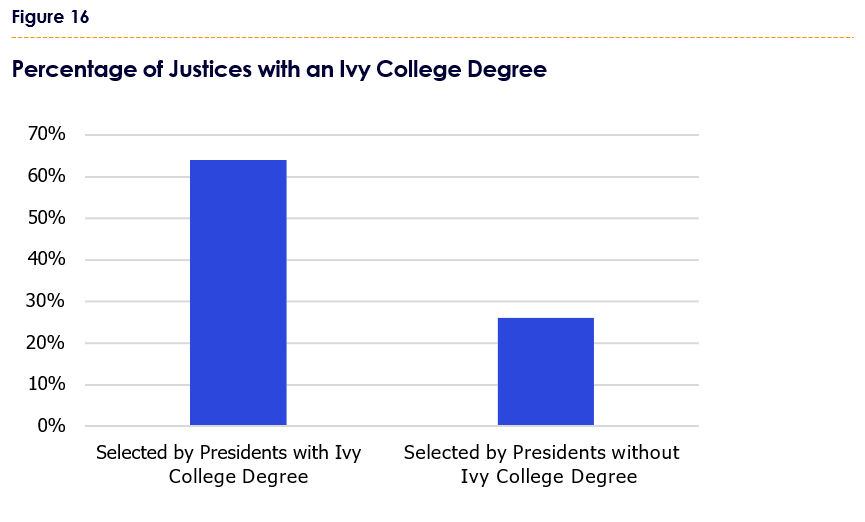

The affinity bias that justices have for clerks is similar to the affinity bias that presidents have for the justices they nominate. Since 1945, 13 presidents have nominated justices to the Court.[41] Presidents who went to an Ivy for college are nearly three times as likely to choose justices who went to an Ivy for college, compared with presidents who went to other schools (Figure 16). Similarly, presidents with any Ivy degree (i.e., undergraduate or graduate) are much more likely to choose justices with any Ivy degree.[42]

Summary: SCOTUS Justices and Clerks

This section tested the hypothesis that the educational background of the choosers matters when it comes to SCOTUS clerkships. I find that justices with Ivy+ and Ivy degrees are significantly more likely to hire clerks with educational backgrounds similar to their own.[43] Moreover, justices with Ivy+ degrees select clerks from a significantly smaller pool of schools.

These findings provide a possible answer to one of the big questions resulting from my previous study. There I found that several prestigious legal positions (state supreme court justices, state attorneys general, and attorneys in leadership positions in states’ most elite firms) are primarily filled by the graduates of public (not private) colleges and law schools and that more of these leaders graduated from flagship publics than Ivy+ colleges and law schools. So why are U.S. Supreme Court law clerks—and potentially those in other elite professional positions—far less likely to have attended flagship and other public schools and much more likely to have attended Ivy+ schools? The likely answer: the affinity bias of the justices hiring them.

To ensure that this finding is not limited to SCOTUS justices and clerks, I collected similar data and applied similar tests to White House Fellowship commissioners and fellows.

White House Fellows and Commissioners

Unlike SCOTUS justices and clerks—all of whom have undergraduate and law degrees—WHF commissioners and fellows have more varied educational backgrounds. A few commissioners do not have a college degree.[44] Some lack a graduate degree. All fellows have undergraduate degrees, but some lack a graduate degree. Moreover, many commissioners and fellows have multiple graduate degrees. Since my primary interest is in whether those with degrees from Ivy+ schools have affinity bias for those with degrees from Ivy+ schools, in this section I will use “any Ivy+ degree.”[45] As before, I begin with descriptive statistics. These data shed light on this important category of leaders and allow for comparisons with SCOTUS clerks.[46]

Descriptive Statistics of White House Fellows and Commissioners

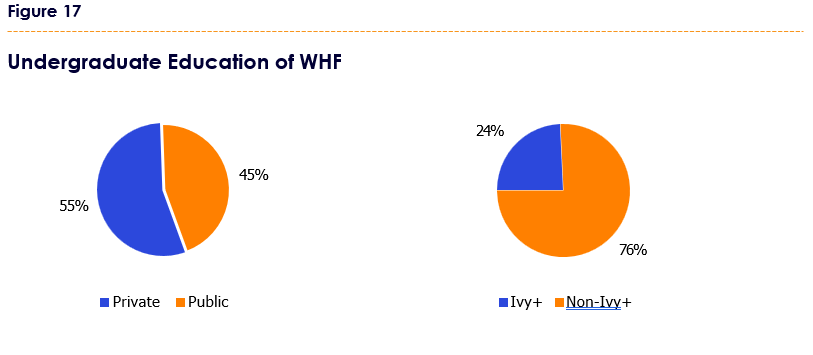

Eight of the 892 WHF (Figure 17). This is very different from SCOTUS clerks, who were nearly 4.5 times more likely to have attended a private college than a public college.

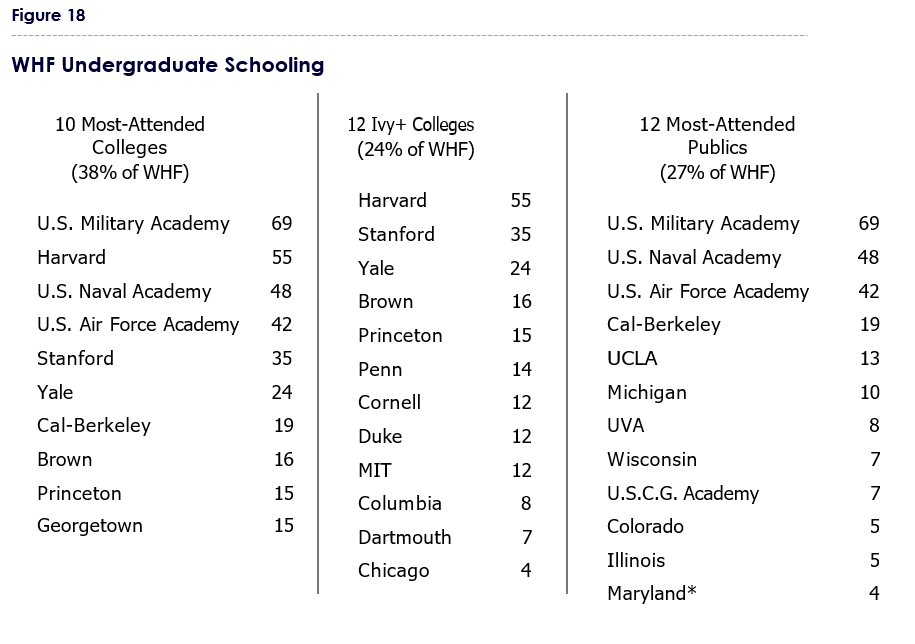

A total of 24% of WHF earned an undergraduate degree from an Ivy+ college, significantly less than SCOTUS clerks (54%). WHF come from a broader collection of colleges, especially military academies, flagship publics, and non-Ivy+ privates. Although my sample of WHF (892) is half the size of the sample of SCOTUS clerks (1,636), more colleges produced WHF (260) than SCOTUS clerks (242). Per capita, WHF come from twice as many schools. The list of clerk-producing schools is also more top-heavy: for clerks, the 10 most common colleges accounted for 54%; for WHF, the 10 most common colleges accounted for only 38% (Figure 18). While the 12 Ivy+ schools figure prominently (24% of WHF), the 12 most-attended publics account for a greater number of WHF (27%).

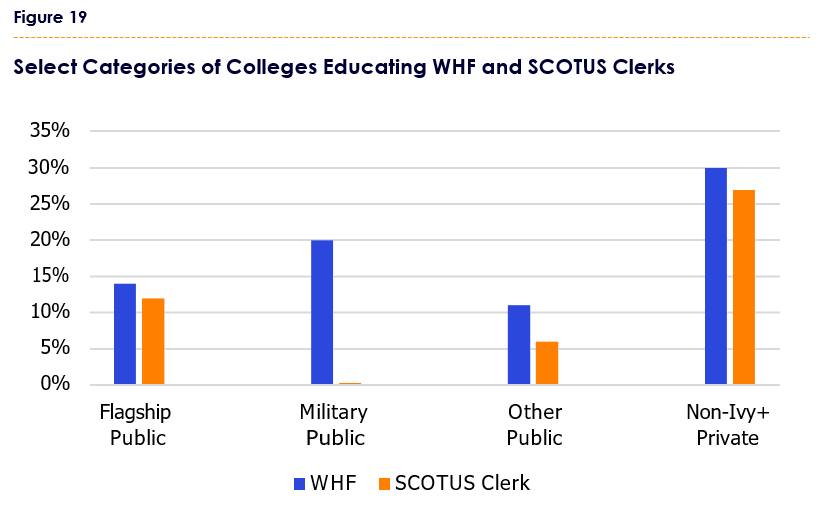

Public military academies produce a far larger percentage of WHF than SCOTUS clerks (Figure 19). About 20% of WHF attended one of eight public military schools for their undergraduate education.[47] Since 1980, only four SCOTUS clerks have attended a military academy for college.[48]

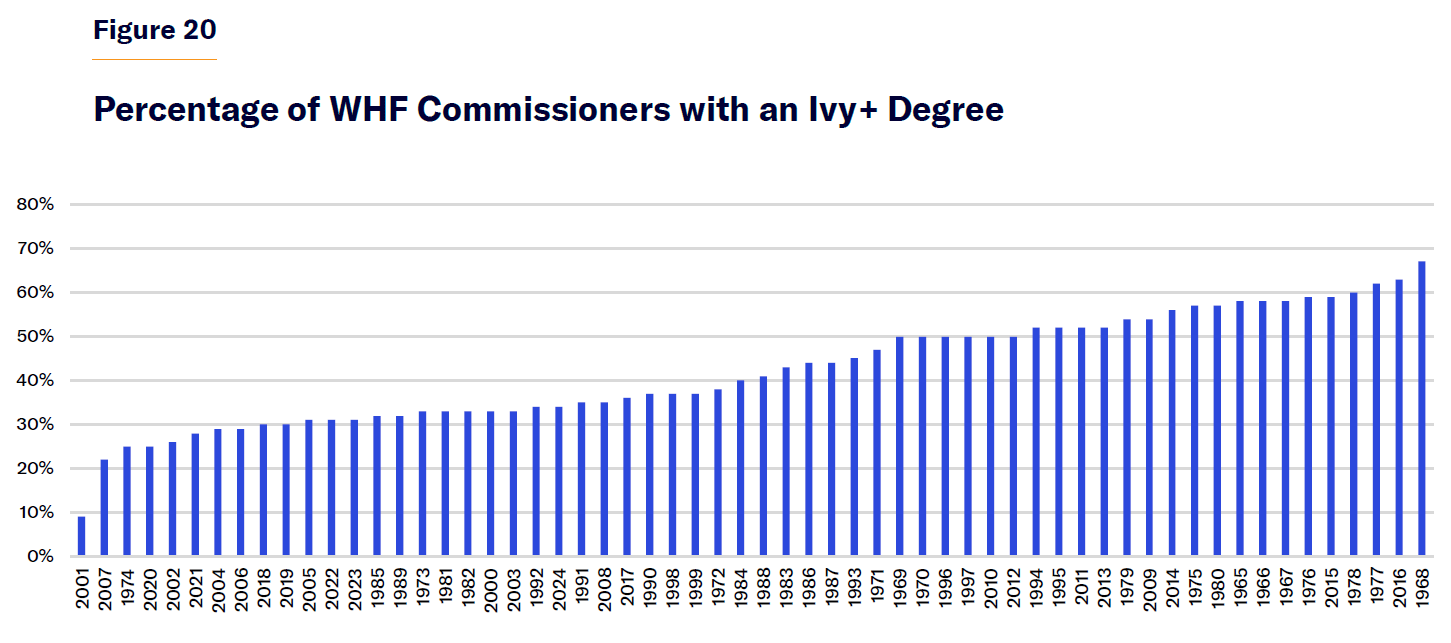

Of the 454 WHF commissioners (those tasked with selecting WHF), 180 earned an Ivy+ degree (40%).[49] If these commissioners were spread evenly across years, we would expect approximately 40% of commission members annually to have an Ivy+ degree. But there is significant variation (presidents often change commissioners when they enter office, commissioners don’t have set terms, commissioners can be replaced by others with different backgrounds, etc.). Figure 20 presents the percentage of commissioners with an Ivy+ degree by year (from lowest to highest). For instance, in 2001, only 9% of commissioners had earned an Ivy+ degree because when President George W. Bush entered office that year, he selected 25 new commissioners, only two of whom had an Ivy+ degree. In 1968, by contrast, 67% (eight of 12) of commissioners had an Ivy+ degree.

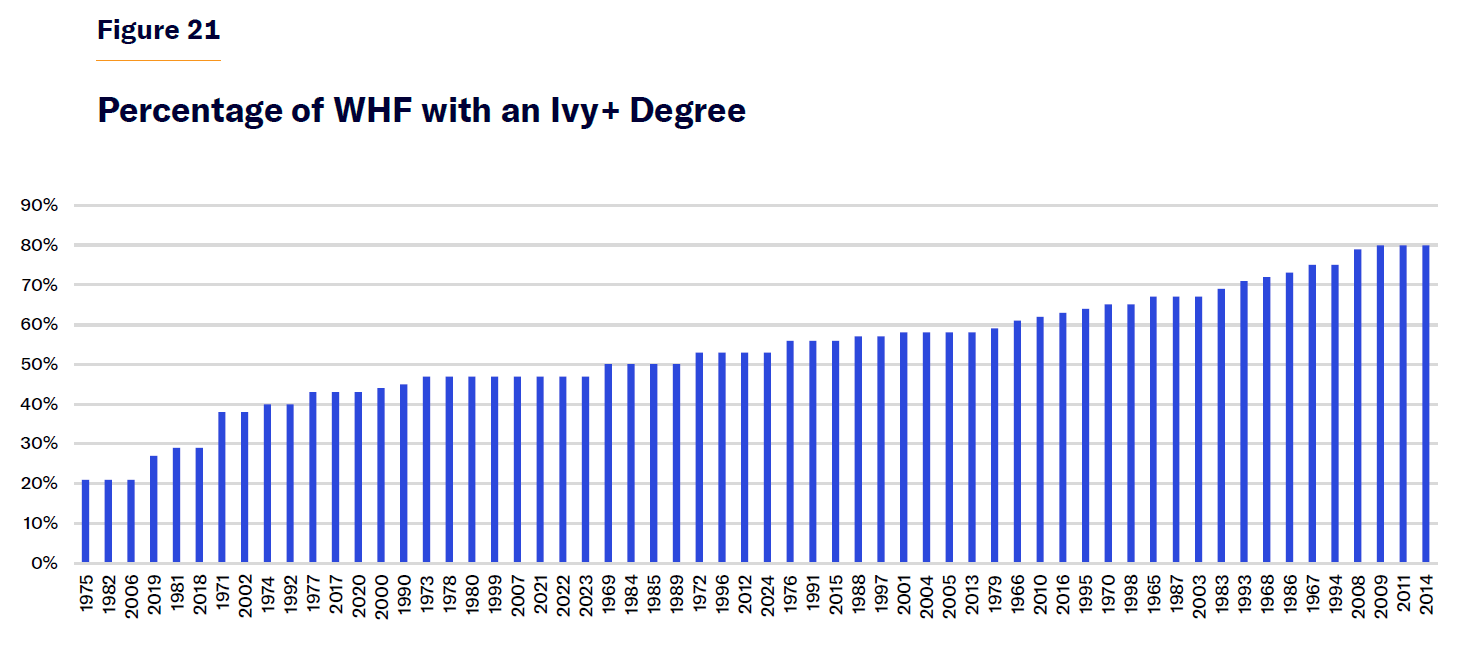

Of the 892 fellows from 1965 through 2024, 478 earned an Ivy+ degree (54%).[50] Again, if these fellows were spread evenly over the years, we would expect about half of each class to possess Ivy+ degrees. But that is not the case. In one six-year period, at least 75% of fellows were Ivy+ graduates; but in a different six-year period, fewer than 30% of fellows were Ivy+ grads (Figure 21). The question is whether the selection of WHF with Ivy+ degrees varies with the percentage of commissioners with Ivy+ degrees.

Linking WHF and Commissioners

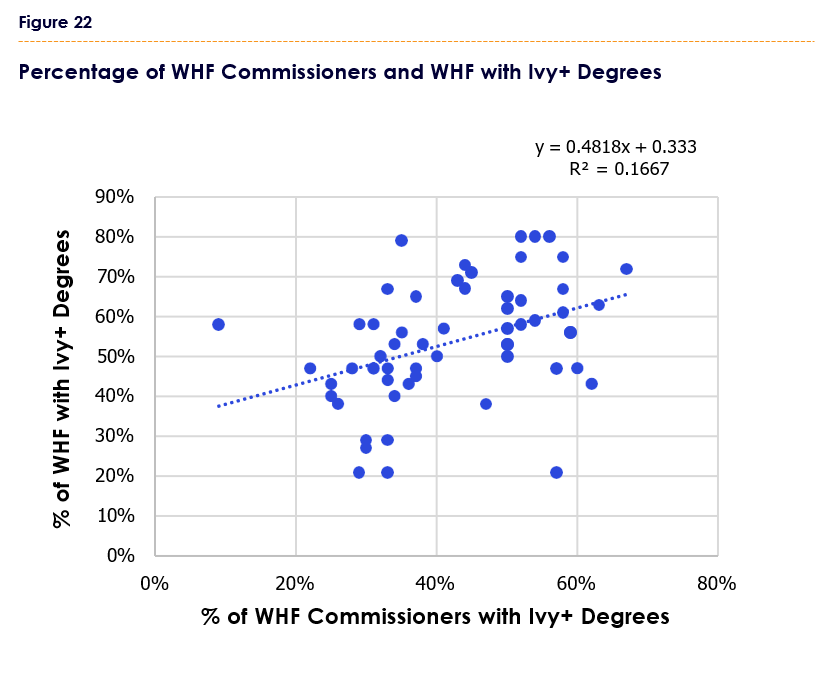

A simple scatterplot begins to show the relationship between the prevalence of Ivy+ degrees among commissioners and the prevalence of Ivy+ degrees among the fellows they select (Figure 22). The two variables are positively related with high statistical significance (p=.001). The relationship can be interpreted simply as: when the percentage of commissioners with Ivy+ degrees increases by 10 percentage points, the percentage of Ivy+ fellows increases by 5 percentage points.[51]

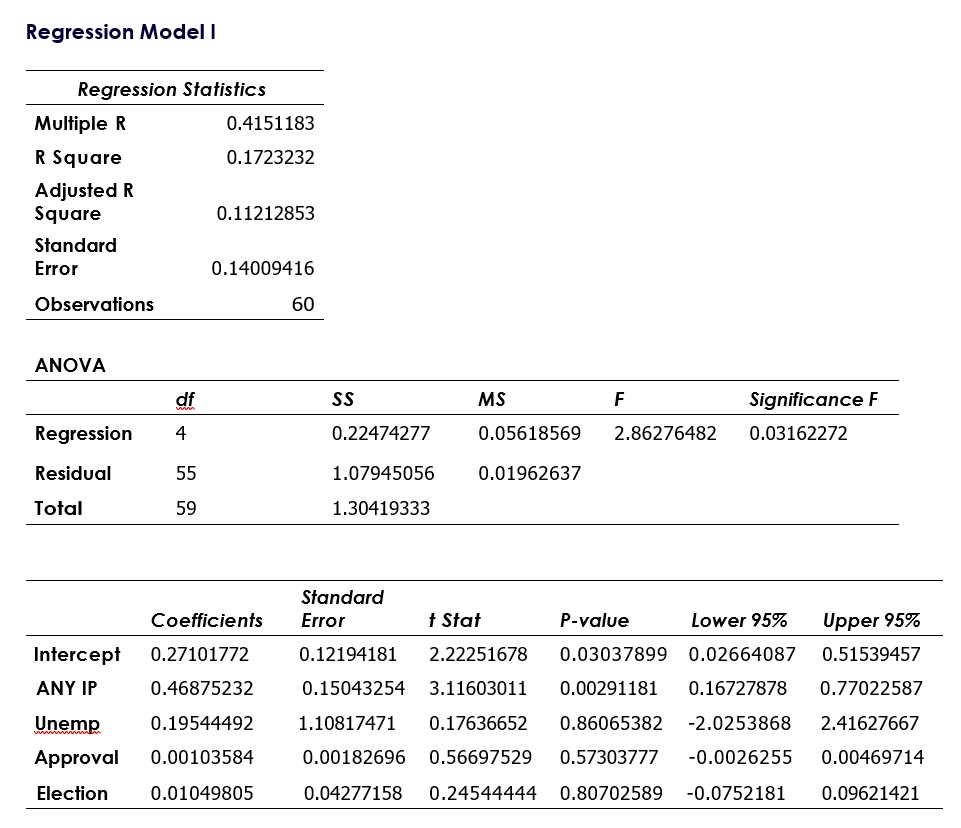

Obviously, other factors could influence the composition of a WHF class, including several related to supply (who would apply) and demand (whom commissioners would prefer to choose). I use a regression model to isolate the influence of commissioners’ education (primary independent variable) on the education of fellows chosen (dependent variable). First, I use three controls that could be expected to influence the percentage of Ivy+ fellows selected.

Presidential Approval

Since Ivy+ graduates have many professional opportunities, they can be picky. A high-quality applicant may not want to work for an unpopular president; the candidate could reason that the president would be ineffective (making the fellowship experience less rewarding) or that having worked for an unpopular president would not look good on the applicant’s future résumé. Since fewer Ivy+ candidates might apply during low presidential-approval years (and more Ivy+ candidates might apply during high presidential-approval years), commissioners might have fewer opportunities to choose Ivy+ candidates when a president is unpopular (and more opportunities when a president is popular).

WHF candidates typically apply at the very end of the calendar year prior to the potential year of selection and service. A candidate hoping to be in the class of 1995–96 (serving from fall 1995 through fall 1996) would complete and submit an application in late 1994.[52] Therefore, I use the Gallup presidential-approval rating for the December when applications are being completed and submitted (in this example, December 1994).[53] In the nine presidential transition years, I use the first approval rating of the incoming president, which is typically in early January.[54]

Unemployment Rate

During economic downturns, it is common for more people to apply to graduate school; with fewer employment opportunities, individuals often invest in their own education, in order to be more marketable during more auspicious economic times. Similarly, Ivy+ candidates may be more likely to apply to the WHF program—as a career investment—during economic downturns. I use the unemployment rate in December of the year preceding potential selection.[55]

Election Year

In election years, it is possible for WHF to end up working for two presidents. Since the fellowship year runs from autumn to autumn, if a new president is inaugurated in the January between, a fellow will work for the end of one administration and the beginning of the next. For example, applicants for 1980–81 (applying in late 1979) knew that they would work, if selected, for President Carter starting in September 1980. But if Carter lost the election in November, the fellow would also work for Carter’s successor, come January 1981 (as happened with the election of Ronald Reagan). Applicants for 1988–89 knew that they would work, if selected, for President Reagan—but also knew, because Reagan was term-limited, that they would work for someone else starting in January 1989.

Ivy+ candidates might choose not to apply during an election year because of this general uncertainty or because they would not want to risk having to work for a president of a party with which they disagreed. For instance, some left-of-center candidates might not have applied for 1980–81 because they didn’t want the possibility of serving under a Republican president, should Carter lose. On the other hand, great candidates might disproportionately apply in election years because of the excitement of a transition period or the chance to be among the first employees of a new administration. For example, high-quality left-of-center candidates might have disproportionately applied for 2008–09 knowing that, if selected, they would have to work for the final months of the

Bush administration but would also potentially get to spend the majority of their time working for a new Democratic administration (as happened with the election of Barack Obama). I use one dummy variable for all presidential election years (1968, 1972, 1976, etc.).

Results

As shown in Appendix F, the percentage of Ivy+ commissioners (“ANY IP”) has a highly statistically significant, positive relationship with the percentage of Ivy+ fellows selected (p=.003). The coefficient (.47) can be interpreted simply as: when the percentage of commissioners with Ivy+ degrees increases by 10 percentage points, the percentage of fellows with Ivy+ degrees increases by nearly 5 percentage points. The three other variables (unemployment rate, presidential approval, and election year) do not have a statistically significant relationship. I then include another set of controls to the model to account for the possible role of different presidents in selection of WHF.

Presidents

I use a different dummy variable for each president serving since 1965.[56] Obviously, presidents are able to influence the selection of fellows by selecting the commissioners. But each president may exert additional influence through other means. For instance, it was well known that President Nixon disliked elite institutions, seeing himself as an outsider. This might have dissuaded Ivy+ graduates from applying, or he might have explicitly or implicitly signaled to his commissioners that he wanted the commission to choose fellows from less elite schools. President Carter, a product of the U.S. Naval Academy and a rural town, may have signaled a preference for public schools or those in out-of-the way communities. Presidents George W. Bush and Obama each had two Ivy+ degrees; perhaps they signaled to their commissioners a belief that the best and brightest attended such schools.

I tested the hypothesis again using a slightly different regression model, the results of which are shown in Appendix G. Once again, the hypothesis was confirmed. In the second model, the percentage of Ivy+ commissioners (“ANY IP”) has a statistically significant, positive relationship with the percentage of Ivy+ fellows selected (p=.017). The coefficient (.71) can be interpreted simply as: when the percentage of commissioners with Ivy+ degrees increases by 10 percentage points, the percentage of fellows with Ivy+ degrees increases by 7 percentage points.

Again, unemployment, presidential approval rate, and election year do not influence the percentage of Ivy+ fellows selected. Two presidential-administration dummy variables had statistical significance at the .05 level: Ford (p=.014) and Carter (p=.042). Both coefficients are negative (though less than half the size of the coefficient for the Ivy+ percentage of commissioners). During the Ford and Carter administrations, fewer Ivy+ fellows were selected, given the other variables (compared with the Johnson baseline).

Conclusion

We now have two pieces of compelling evidence of the affinity bias of Ivy+ graduates as selectors for elite public positions. Exceptionally talented people serve as U.S. Supreme Court justices. But justices with Ivy+ degrees choose significantly more Ivy+ clerks than justices with other degrees.

Exceptionally talented people serve as commissioners of the White House Fellowship program. But when the commission has more Ivy+ graduates, the commission chooses more fellows with Ivy+ degrees.

When put in human terms, the size of these effects is notable. Over the course of a 25-year career on the Court, a justice from a non-Ivy+ college will hire 17 more clerks who went to non-Ivy+ colleges. A justice from a non-Ivy law school will hire 22 more clerks who went to non-Ivy law schools. Over the course of its history, had the prevalence of Ivy+ members on the White House Fellowship commission been cut from 40% to 20%, we could have expected 125 more White House Fellows without an Ivy+ degree.

We should now feel confident saying that one reason some institutions seem to be perpetually overpopulated with Ivy+ graduates is that Ivy+ graduates disproportionately elevate people like themselves. To be clear, we do not know why that is the case. Maybe they believe that all the highest-ability people attended the schools similar to those that they attended. Maybe they believe that the value of their own degrees increases if others with the same degrees succeed professionally. Maybe there are other reasons. Regardless, those without Ivy+ degrees will have less of a chance at securing an elite position if Ivy+ graduates are in charge.

These findings prompt at least three conclusions. First, we must make Ivy+ graduates in positions of power aware of their proclivity for affinity bias. They must be alerted to the likelihood that they will select and promote people with whom they share an educational background. This means that they probably are not giving sufficient opportunities to those with other backgrounds and that they are—purposely or inadvertently—creating and maintaining homogeneous organizations.

Second, although this study covered SCOTUS clerks and WHF, its lessons may apply to a vast array of elite professional settings. If we observe an organization, fellowship, or scholarship consistently overpopulated by Ivy+ graduates, we should ask whether affinity bias is at play. If Ivy+ graduates also predominate among the selectors in one of these institutions, we should assume that affinity bias is at play. Examples of entities that warrant study, if not scrutiny, include the Rhodes and Marshall Scholarships, the Fulbright Program, MacArthur Fellowships, academic societies, faculty hiring committees, and CEO search committees. Based on this study, it appears that Ivy+ graduates dominate in certain prestigious and influential entities at least partly because choosers identify with them. If so, society’s leadership ranks have been and continue to be distorted by affinity bias.

Third, we may be able to dramatically expand opportunity by decreasing the number of Ivy+ graduates in selector positions. Non-Ivy+ selectors do not deny opportunities to Ivy+ graduates. The evidence shows that non-Ivy+ justices still hire many Ivy+ clerks. When the WHF commission has few Ivy+ members, it still selects many Ivy+ fellows. But limiting the percentage of Ivy+ selectors does open the door to a greater number of talented non-Ivy+ candidates.

Appendix A

The education profiles of state supreme court justices are very similar whether they are selected via an election or by the governor and an expert commission (Figure A1 and A2). None of the differences are statistically significant apart from Ivy+ degrees at the law-school level (16% vs., 7%; p=.02; one-tail). Even still, both methods produce a fraction of the Ivy+ law degrees seen among U.S. Supreme Court justices (79% since 1980) and clerks (71% since 1980).

Appendix B

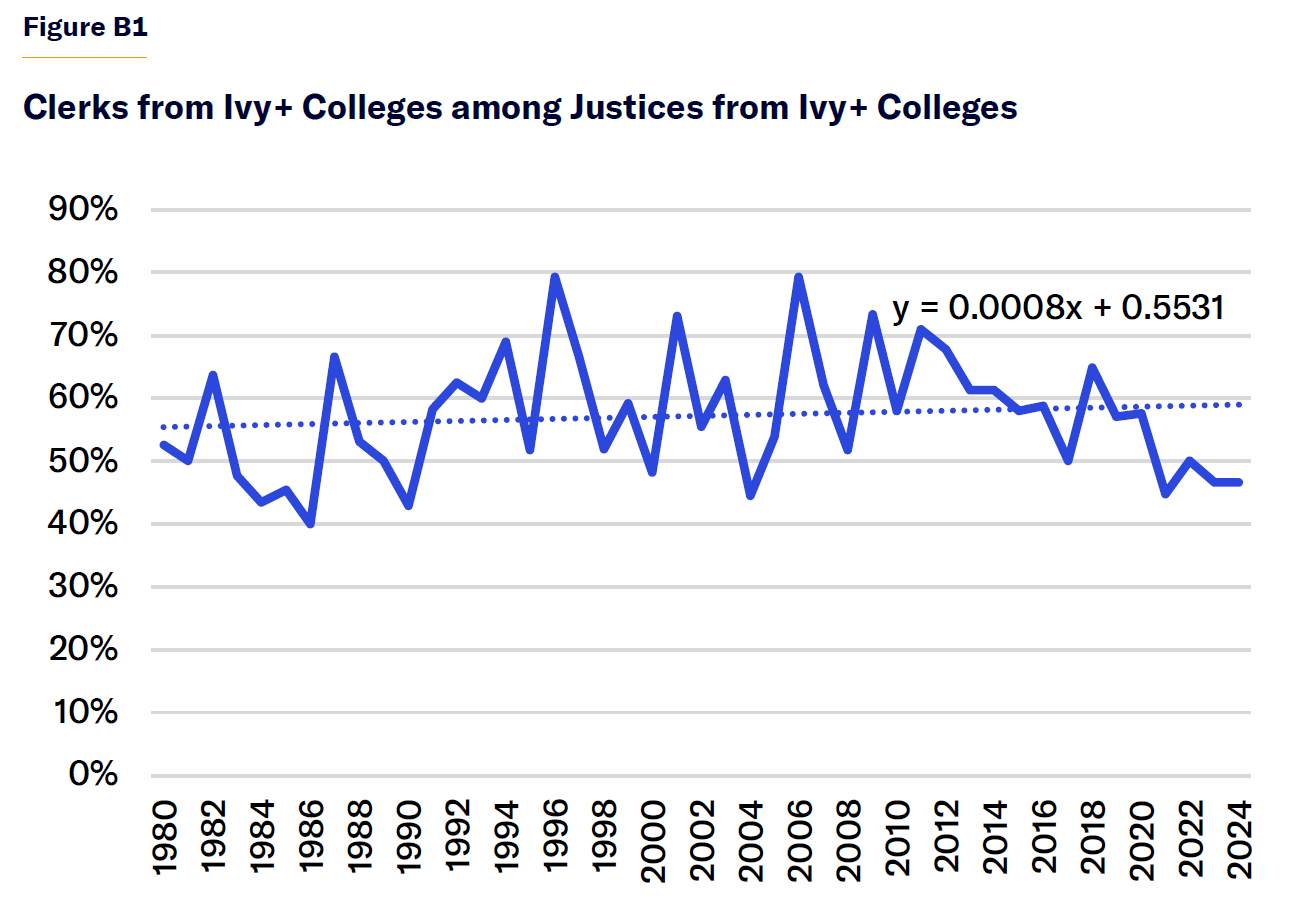

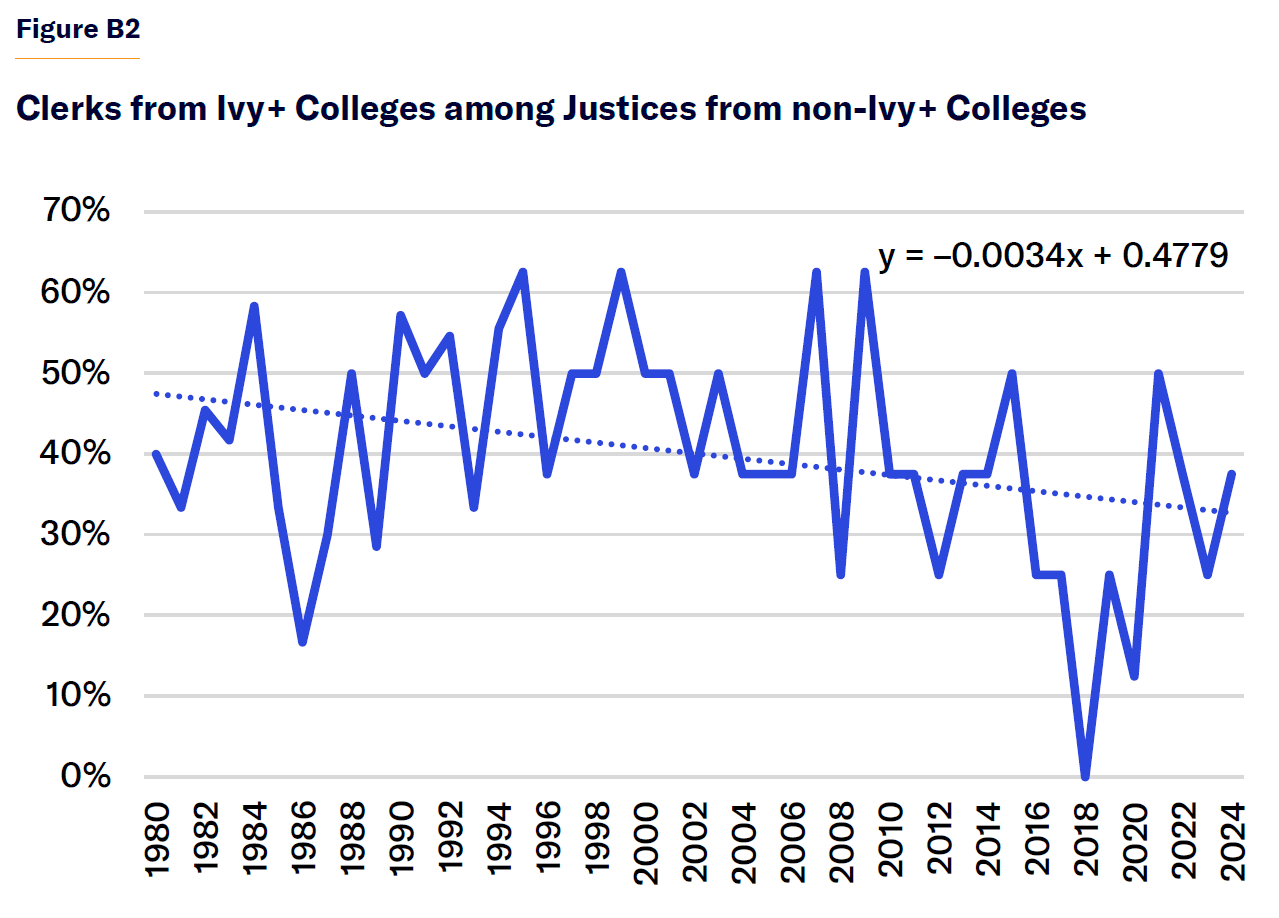

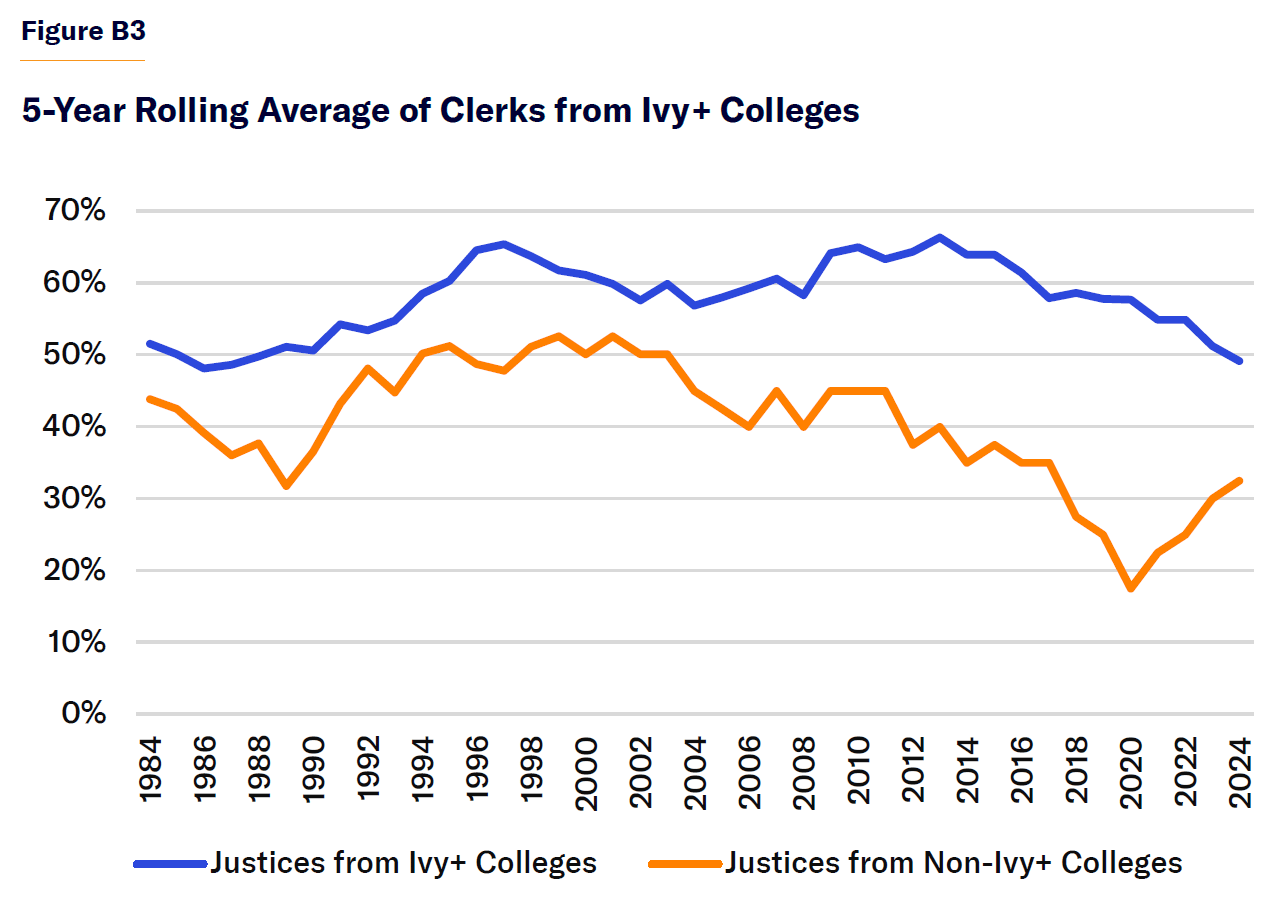

It is possible that society has become more partial to Ivy+ graduates over time. If so, my results could be attributed to this shift instead of Ivy+ affinity bias. Imagine that “choosers” years ago were ambivalent about Ivy+ grads while “choosers” today are favorable toward them. If more Ivy+ grads are in “chooser” positions now, they would choose more Ivy+ grads today not due to of affinity bias but because anyone in a chooser position today would choose more Ivy+ graduates. To test this explanation, I compare the annual selection of clerks by Ivy+ justices and non-Ivy+ justices.

There is no discernible upward trend among Ivy+ justices (Figure B1). They are as likely to select Ivy+ clerks today as in years past. There is more fluctuation among non-Ivy+ justices, but that is largely because there have been few non-Ivy+ justices (Figure B2). In four years, Justice Thomas was the only non-Ivy+ justice. In 2018, all four of his clerks graduated from non-Ivy+ colleges.

To smooth annual fluctuations, I used a five-year rolling average (Figure B3). Justices with Ivy+ undergraduate degrees choose more clerks with Ivy+ college degrees, and that percentage is stable over time. Justices from non-Ivy+ schools choose fewer, and that percentage has decreased over time. A general growing fondness for Ivy+ graduates cannot explain this study’s results.

Appendix C

To assess the possibility of an alma-mater effect, I compared the hiring choices of the alumni of a school to the hiring choices of non-alumni. Since I found that Ivy+ justices hire more Ivy+ clerks than non-Ivy+ justices, we would expect justices who graduated from Harvard to choose more Harvard-educated clerks than non-Ivy+ justices. But if this is driven primarily by an alma-mater effect, we would also expect Harvard-educated justices to hire more Harvard-educated clerks than do Ivy+ justices who didn’t go to Harvard. Said another way, Ivy+ affinity bias would suggest that Ivy+ justices should have similar hiring preferences among Ivy+ schools. But an alma-mater effect would suggest that Harvard justices choose far more Harvard clerks (and Yale justices would choose far more Yale clerks, etc.) than clerks from other Ivy+ schools.

But as Figure C1 shows, eight Ivy+ colleges claim at least one justice as an undergraduate alumnus, and in four of those instances (Harvard, Yale, Columbia, Chicago), the alumni (column 3) on average hire a lower percentage of clerks from their alma mater than Ivy+ justices who went to other schools (column 4). In four cases (Princeton, Penn, Stanford, Cornell), the alumni on average hire a higher percentage from their own alma mater. But in all instances, the differences are remarkably small. Harvard grads hire about 15% of their clerks from Harvard on average, while Ivy+ justices from schools other than Harvard hire about 18% of their clerks from Harvard. The four Stanford grads hired 3%, 4%, 4%, and 5% of their clerks from Stanford respectively, while Ivy+ non-Stanford grads hired about 3% from Stanford.

The justice who, on first blush, appears to have the largest alma-mater preference is Souter (Harvard). He selected 30% of his clerks from Harvard, well above the 17% average. But Souter hired more clerks from Ivy+ colleges than any other justice; as such, he also hired a disproportionately high percentage of clerks from Ivy+ schools that were not his alma mater. For example, he hired a higher percentage of clerks from Yale than the two justices who graduated from Yale, and he hired a higher percentage of clerks from Columbia than the justice who graduated from Columbia. Probably the clearest instance of an alma-mater preference is Brennan. Most justices hired 1% to 4% of their clerks from Penn; Brennan (the only Penn grad) hired nearly 10% from Penn. But at the same time, eight justices picked a smaller percentage of clerks from their alma maters than the average of Ivy+ justices.[65]

Although this strongly suggests that the Ivy+ affinity bias is not driven by an alma mater effect, I adjusted the data in three ways to control for any meaningful alma matter effect. In the first adjustment, I make each Ivy+ justice’s alma-mater percentage equal to the average of Ivy+ justices who are not alumni of that justice’s alma mater; and then I reallocate the excess using the justice’s ratio of Ivy+/non-Ivy+ hiring.

For example, Ivy+ Justice Kagan hired 70% of her clerks from Ivy+ colleges; 10% of her clerks came from her alma mater, Princeton. Ivy+ justices who did not go to Princeton hire only 6% of their clerks from Princeton. So, in this adjustment, Kagan’s Princeton percentage is limited to 6%. That excess of 4 percentage points (10% – 6%) is then reallocated to the other colleges from which Kagan chose clerks. This attempts to answer the question,“If Kagan had not hired those clerks from Princeton, where would have she hired them from?” Removing Princeton from consideration, Kagan hired 2/3 of her clerks from other Ivy+ schools and 1/3 from non-Ivy+ schools. So, 2/3 of the excess is allocated to the Ivy+ category and 1/3 to the non-Ivy+ category. Kagan’s Ivy+ percentage first goes down from 70% to 66% (because her Princeton percentage is dropped from 10% to 6%), then goes up from 66% to 68.7% (because 2/3 of the excess 4 percentage points [2.7] is reallocated to other Ivy+ schools).

This method has an intuitive and practical appeal. Adjusting a justice’s alma-mater percentage in this way mimics how non-alumni justices hire clerks from that school. By reallocating “excess” clerks, it maintains each justice’s number of clerks (i.e., by parceling out the same number of clerks differently). By reallocating excess clerks based on the justice’s revealed Ivy+/non-Ivy+ preferences, it fairly approximates what a justice would have done had there been a cap on her hiring from her alma mater. For example, if an Ivy+ justice only hired Ivy+ clerks from her alma mater (i.e., the alma-mater effect entirely drives the Ivy+ affinity bias effect), the justice would see the maximum adjustment: 100% of her alma-mater hires above the non-alumni average would be relocated to non-Ivy+ schools. If the justice only hired Ivy+ clerks, 100% of her alma-mater hires above the non-alumni average would be relocated to other Ivy+ schools.

In Figure C2, “Adjusted 1”, this adjustment is made to the Ivy+ percentage of all Ivy+ justices.[66] Because few Ivy+ justices disproportionately choose clerks from their college alma maters, the adjusted figures are very similar to the unadjusted figures (Compare Figure C2 to Figure 11). There is still a highly statistically significant difference (p=0.002). The alma mater effect is not driving the affinity-bias effect.

I use two supplemental adjustments to confirm this finding. In Figure C3, (“Adjusted 2”), I adjust, as above, each justice’s alma-mater percentage to the Ivy+ non-alumni percentage for that school. Unlike above, I do not reallocate the excess percentage of clerks. That excess disappears.[67] As above, some justices’ scores are adjusted up because their alma-mater percentage was below the Ivy+ non-alumni percentage for that school. Adjusted 2 is nearly identical to Adjusted 1 (averages and p-value), indicating again that the alma-mater effect is not driving the affinity bias effect.

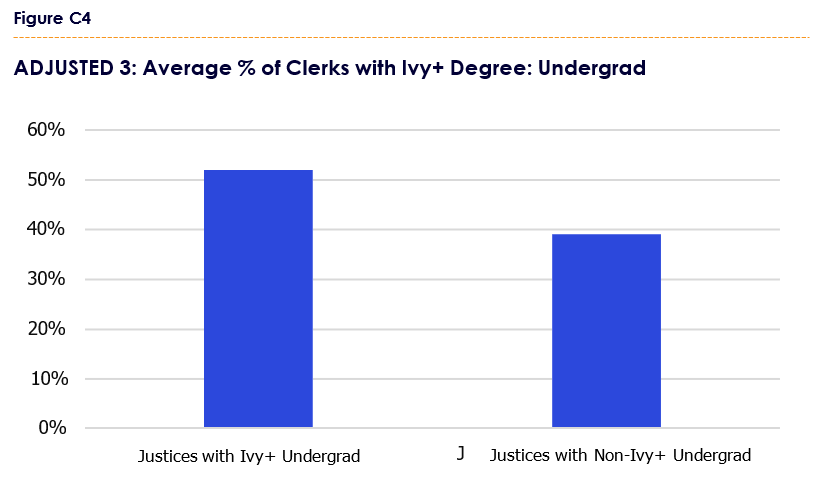

Lastly, in Figure C4 (“Adjusted 3”), I remove each justice’s alma mater entirely. Each Ivy+ justice’s Ivy+ percentage is therefore composed of 11 schools instead of 12. This is a stringent, even exaggerated, method of erasing any possible alma-mater effect.[68] All justices’ Ivy+ percentages are adjusted down using this approach.[69] This method results, again, in a statistically significant difference. The finding is Ivy+ affinity bias, not an alma mater effect.

Appendix D

As above, I assess whether Ivy+ justices have affinity bias for Ivy+ clerks or if Ivy+ justices are simply hiring clerks from their alma maters. Appendix C relates to undergraduate education; here, I focus on law schools.

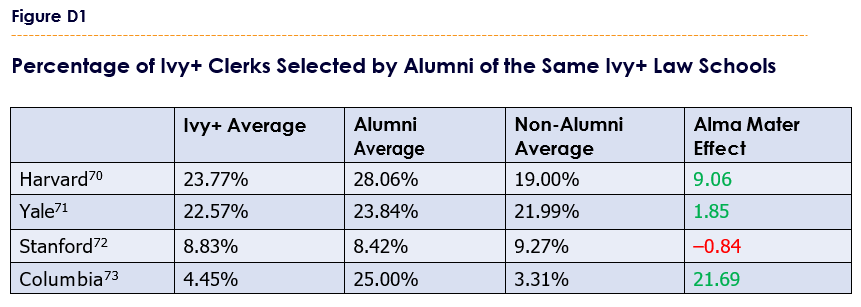

First, I replicate Figure C1 for law schools. Ivy+ justices since 1980 graduated from only four different law schools (Harvard, Yale, Stanford, Columbia). Yale- and Stanford-graduating justices hire from their alma maters at a rate comparable to justices who are not alumni of those schools (columns 3 and 4). Harvard graduates and the one Columbia graduate hire more clerks from their alma maters than non-alumni (Figure D1). The question, though, is whether the statistically significant preference that Ivy+ justices (compared to non-Ivy+ justices) have for Ivy+ clerks is driven by an alma-mater effect.

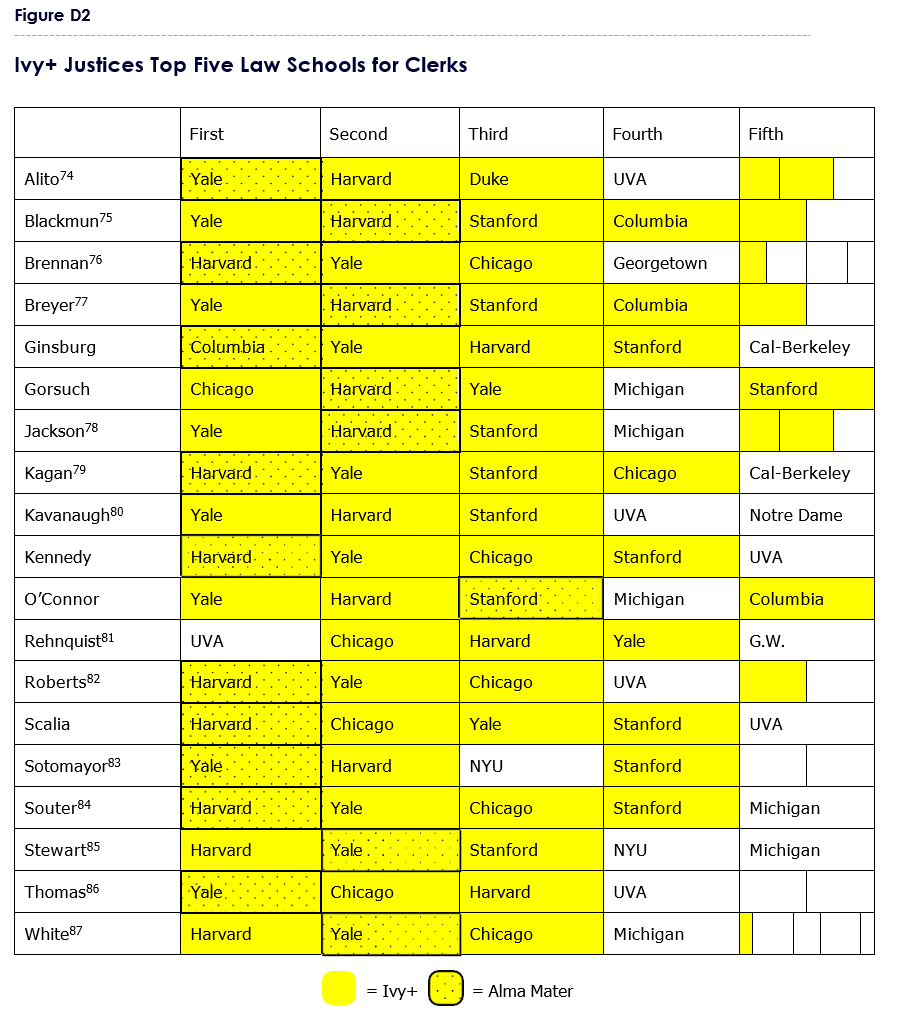

Ivy+ law-school justices hire, on average, more than 70% of their clerks from Ivy+ law schools. So while they (at least in the case of Harvard and Columbia) hire more often from their alma maters, they also hire most of their clerks from other Ivy+ law schools. For example, Harvard justices hire 28% of their clerks, on average, from Harvard Law, but those Harvard justices hire, on average, an additional 50% of their clerks from other Ivy+ schools (the average Harvard Law justice hires 78% of his/her clerks from Ivy+ schools). Figure D2 shows, for each Ivy+ justice, which five law schools s/he hires from the most. Yellow boxes indicate an Ivy+ law school. Patterned boxes with the emphasized outline are each justice’s alma mater. So, for instance, Ginsburg hired most often from her alma mater Columbia, second most often from Yale, etc.

Two things stand out. First, Ivy+ law schools typically make up four of each Ivy+ justice’s top five schools for clerks. In fact, only two of the 19 justices have a school in their top three that is not an Ivy+. Second, the top law school for 8 of the 19 justices is not their alma mater. Rehnquist’s alma mater is not even in his top five. These data demonstrate that these justices are choosing from an array of Ivy+ law schools, not simply their alma maters. But to confirm, I apply the same three adjustments from Appendix C.

As above, in the first adjustment, I make each Ivy+ justice’s alma-mater percentage equal to the average of Ivy+ justices who are not alumni of that justice’s alma mater; then I reallocate the excess using the justice’s ratio of Ivy+/non-Ivy+ hiring (Figure D3). Because these justices hire clerks from an array of Ivy+ schools, even sometimes hiring more clerks from law schools that are not their alma maters, this adjustment alters the true data minimally (compare Figure D3 to Figure 13). The results are still highly statistically significant. The alma-mater effect does not drive the Ivy+ affinity bias effect.

In Figure D4 (“Adjusted 2”), I use the same second adjustment as above: Each justice’s alma-mater percentage is set to the Ivy+ non-alumni percentage for that school, and the excess percentage of clerks is not reallocated. As above, the highly statistically significant difference remains. In Figure D5 (“Adjusted 3”), as above, I remove each justice’s alma mater entirely.88 The difference remains and is significant at the 0.1 level. The alma-mater effect is not the cause of the affinity-bias finding.

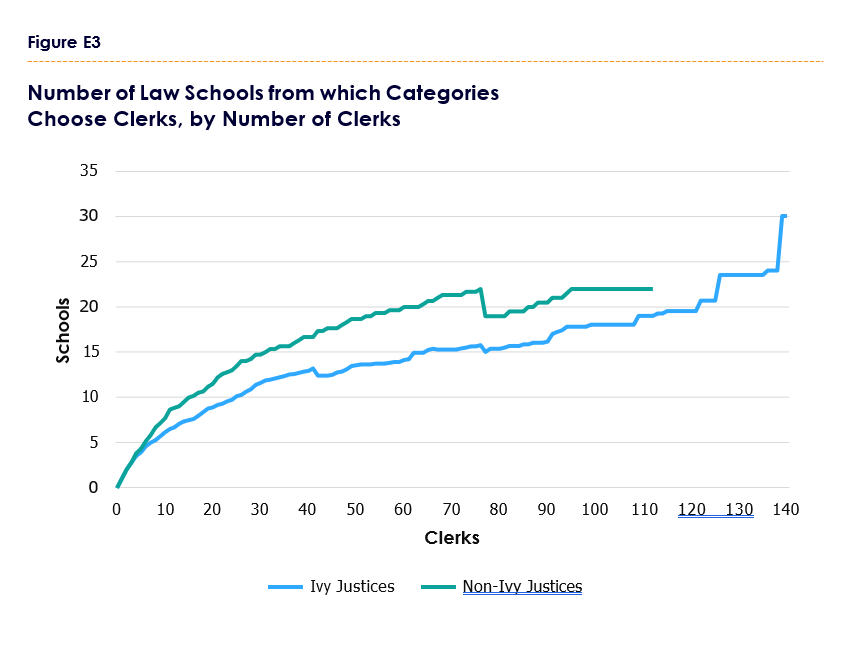

Appendix E

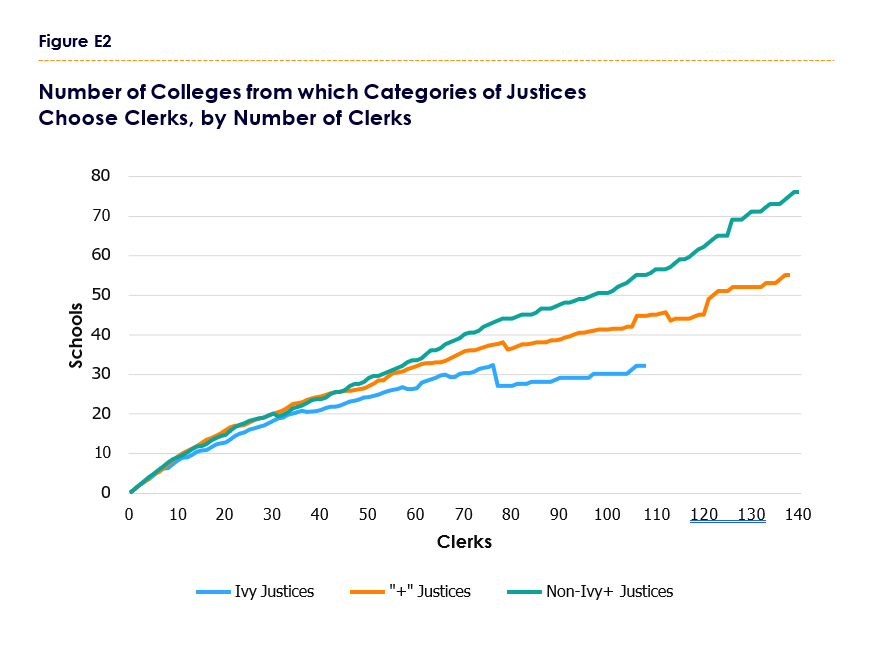

In order to control for a justice’s tenure on the Court, I show how the number of clerks hired by a justice relates to the number of schools from which that justice hires clerks. Figure E1 is illustrative of how very different justices’ preferences can be. The x-axis shows the number of clerks selected by the justice, and the y-axis shows how many different schools those clerks came from. At any point on a justice’s line, the x-axis shows how many clerks that justice had hired, and the y-axis shows how many different schools those clerks came from. That point can be read as, “After hiring X clerks, this justice had hired from Y different schools.”

I show the three justices who hired from the smallest universe of colleges: Ginsberg, Kagan, and Souter. All three graduated from an Ivy college. I also show the three justices who hired from the largest universe of colleges: Rehnquist, Scalia, and Thomas. All three graduated from non-Ivy colleges. The justices’ lines are different lengths because they hired different numbers of clerks (based on time on the bench). After choosing 40 clerks (about 10 years on the Court), the three Ivy justices had hired clerks from an average of 16 schools; the three non-Ivy justices hired from an average of 24 schools. By 60 clerks, the gap is 14 schools and continues to grow.

In Figure E2, I show the average number of schools from which clerks are selected for all 12 Ivy justices, the 5 “+” justices (graduates of Stanford and Chicago), and the 6 non-Ivy+ justices. Contrary to the concern that length of justice tenure could distort the diversity index, Ivy justices hire from the smallest universe of schools, and non-Ivy+ justices from the largest. Note that as each line moves to the right, it includes fewer justices because some justices have hired different numbers of clerks. For example, the Ivy line is the average of 12 justices from 1–6 clerks; by 13 clerks, it includes 10 justices, by 60 clerks, 6 justices, etc. This is how the average of Ivy justices can drop after 76 clerks. Alito and Roberts (who hired from the largest universe of schools among Ivy justices) only had 76 clerks, so the post-76 average no longer includes Alito and Roberts.

Similarly, Figure E3 shows the average number of law schools from which justices selected clerks. Since 1980, only two justices graduated from “+” law schools (Rehnquist and O’Connor, Stanford) and only four justices graduated from non-Ivy+ law schools, so I combine the “+” and the “non-Ivy+” into one “non-Ivy” category. Once again, regardless of years on the Court, Ivy justices choose clerks from a smaller universe of schools than non-Ivy justices. Note, the Ivy justice line spikes after clerk 138 because Thomas is the only Ivy justice with more than 138 clerks, and he is the Ivy justice who pulled from the largest universe of law schools.

Appendix F

Appendix G

Endnotes

Photo by UCG / Contributor via Getty Images

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).