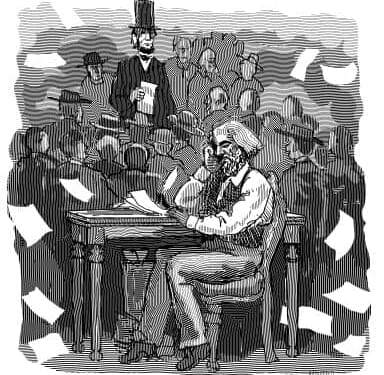

Frederick Douglass’s best-known assessment of Abraham Lincoln was offered in his 1876 Oration, delivered at the unveiling of the Freedman’s Memorial, the first sculpture to honor the martyred president and, according to Douglass, the first “national act” of the emancipated people, expressing gratitude for their “blood-bought freedom.” With the benefit of hindsight, Douglass acknowledged the all-inclusive statesmanship of Lincoln, who managed both “to save his country from dismemberment and ruin,” and “to free his country from the great crime of slavery.” Significantly, Douglass also admits the incompleteness of his own earlier perspective which had been focused solely on abolition; hence he had found Lincoln to be “tardy, cold, dull, and indifferent.” Yet, in retrospect, “measuring him by the sentiment of his country, a sentiment he was bound as a statesman to consult,” Douglass concluded that Lincoln was “swift, zealous, radical, and determined.” Douglass’s revised judgment is not simply the result of the difference between foresight (which scant few possess) and hindsight but more fundamentally between radicalism and political prudence (the intellectual virtue the Greeks called phronesis). It seems that Douglass’s yardstick for Measuring the Man, to borrow the title of this invaluable new collection of his writings on Lincoln, altered over the years.

***

Compiled by Lucas E. Morel, the John K. Boardman, Jr. Professor of Politics at Washington and Lee University, and Jonathan W. White, professor of American Studies at Christopher Newport University, the anthology gathers remarks culled from speeches, editorials, and letters from 1858 to 1894, including a dozen previously unknown pieces. I must confess that in reading through these reflections, I was as much interested in “measuring the man” Douglass as in “measuring the man” Lincoln.

Lincoln first came to the notice of the abolitionist orator during the 1858 electoral contest with the other Douglas: Stephen A. That Douglas, by the way, had dropped the second “s” from his surname in 1846, after he was already well launched on his political career, possibly in response to the 1845 publication of Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself and the increased prominence of its author. Douglass always enjoyed tweaking the homonymous “white Douglas,” as he does in the book’s first selection: “Once I thought he was about to make the name respectable, but now I despair of him, and must do the best I can for it myself.” Douglass’s initial take on Lincoln, based on the House Divided address, is entirely positive. He praises “the great speech of Mr. Lincoln,” quoting from its opening analysis of the incompatibility between slavery and freedom, and declaring it “well and wisely said.” It’s not surprising that Douglass would have responded enthusiastically to the House Divided speech. Delivered as a convention speech to his base of Illinois Republicans, it stands as Lincoln’s most partisan performance, quite different in tone from speeches in which he was at pains to persuade the uncommitted.

***

Two years after the House Divided speech, Lincoln became the Republican nominee for the presidency. Although Douglass would have preferred New York governor William Seward, he again offered praise for Lincoln, singling out his integrity: “he is a man of will and nerve, and will not back down from his own assertions.” Nonetheless, dissatisfaction with Lincoln emerged pretty quickly. A month after the nomination, Douglass wrote privately to former New York congressman Gerrit Smith, hoping for an abolitionist candidate and stating: “I cannot support Lincoln.” By October, he was editorializing against the Republicans and their candidate, whom he characterized as “for slave-hunting at the North, and slaveholding at the South.” That summary was ungenerous but not entirely inaccurate, inasmuch as Lincoln believed there was a constitutional duty to return runaway slaves and that there was no federal authority (under normal circumstances) to interfere with slavery in the slave states. Despite his doubts, Douglass welcomed the election of Lincoln as inaugurating “a new order of events,” that had at least vitiated the power the slave oligarchy had over Northern politicians and voters. Douglass expected the Southern fire-eaters to cool off when they realized that Lincoln was no abolitionist and that slavery would be quite safe under the incoming administration. His prediction in December 1860 was that the Union, regrettably in his view, would “be saved simply because there is no cause in the election of Mr. Lincoln for its dissolution.”

Douglass’s analysis of the election, well argued and plausible in many respects, reveals his blind spot. For him, abolition—immediate and comprehensive—was the only true anti-slavery position. He simply did not believe that slavery in the territories could be the crux of the issue. But it seems that the Southern slaveholders viewed the matter as Lincoln did. For them, the election of Lincoln, achieved in the face of their threats of disunion, did indeed spell the doom of their peculiar institution, what Lincoln called its “ultimate extinction.” Regardless of how far distant “ultimate” might be, the policy of non-extension Lincoln backed returned the nation to the founding principle of equality and branded slavery as an evil to be tolerated only by “necessity.” This moral regeneration was decisive. What Douglass had liked about the House Divided speech was the notion that the nation could not remain half slave and half free but must somehow become all one thing or all the other. The uncompromising Bible-based formulation resonated with Douglass. But he had not fully absorbed or agreed with the moderate character of Lincoln’s reasoning about these opposite possibilities. Lincoln insisted that the proper, constitutional path to All Free was through the Republican policy of opposing the spread of slavery into the territories. Douglass instead announced, with his usual fervor, that he would “join in no cry, and unite in no demand less than the complete and universal abolition of the whole slave system.”

***

By January 1861, when southern dissatisfaction with the election crossed over into insurrection, Douglass responded with another editorial, ably detailing the legal fallacy of the South’s pretended “right of peaceful secession.” Although Lincoln would not be inaugurated for another two months, Douglass correctly predicted that the incoming president would be true to his oath of office and not succumb to the dissolution of the Union “by force, by treachery, or by negotiation.” Based on Lincoln’s “refusal to have concessions extorted from him”—as in his rejection of the Crittenden Compromise, the eleventh-hour Senate proposal to stave off Civil War—and “the cool and circumspect character of his replies,” Douglass predicted that Lincoln would do better than “the shuffling, do-nothing policy of Mr. Buchanan.”

Nonetheless, Lincoln’s inaugural address was greatly disappointing to Douglass. He had hoped that the new president would “boldly grapple with the monster of Disunion”; instead, what he heard was appeasement, even abasement, although he also discerned a contrasting note of firmness, marking the address as “a double-tongued document, capable of two constructions…[it] conceals rather than declares a definite policy.” Whereas Douglass wanted the Slave Power humbled, Lincoln reached out “to those…who really love the Union.” In speaking to “dissatisfied fellow countrymen,” he insisted or maybe pleaded: “We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies.”

Neither the logos nor pathos of Lincoln’s First Inaugural could avert war. As he said in his Second Inaugural: “And the war came.” The editors of this volume wisely divide Douglass’s speeches and writings during the war into two phases: pre- and post-Emancipation. Because Douglass had intuited that the war could end slavery, he was distressed by any temporizing measures that cut against that abolitionist aim. So, for example, he disliked Lincoln’s solicitousness toward the loyal, slaveholding states—the so-called “border states.” (Lincoln, by the way, rejected that label; there was no interior “border,” since “in view of the Constitution and the laws, the Union is unbroken.”) To Douglass, Lincoln’s prudence was “pusillanimous.” He professed himself “bewildered by the spectacle of moral blindness—infatuation and helpless imbecility which the Government of Lincoln presents.” Nevertheless, in March 1862, Douglass was temporarily cheered by Lincoln’s message to Congress recommending federal aid for gradual emancipation if undertaken voluntarily by the states (in other words, those states that Lincoln had been assiduously courting, much to Douglass’s disgust). Douglass now claimed to “read the spaces as well as the lines of that message,” seeing therein “a brave man trying against great odds, to do right.” But, for Douglass, there was simply too much twisting and turning. His speech on July 4, 1862 was highly critical of the administration, offering a litany of policy mistakes that Douglass construed as effectually pro-slavery. His outrage reached its peak during September 1862 after Lincoln met with a delegation of prominent black Washingtonians, asking them to consider colonization, at least on a small, experimental scale. Douglass was furious, accusing Lincoln of “showing all his inconsistencies, his pride of race and blood, his contempt for negroes and his canting hypocrisy.” The unsparing attack denounced not only the policy but Lincoln’s character: “passive, cowardly, and treacherous to the very cause of liberty to which he owes his election.” Even the president’s plain style of speech came in for abuse: “Mr. Lincoln…in all his writings has manifested a decided awkwardness in the management of the English language.”

***

Then, on September 22, 1862, Lincoln issued the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation and Douglass gave a “shout for joy that we live to record this righteous decree.” (Lincoln’s dramatic deed in September should perhaps have led Douglass to reevaluate the intent behind various public relations initiatives in August, including not only the meeting with the black delegation but also his public letter to Horace Greeley and his meeting with a group of Chicago ministers.) Noting Lincoln’s “peculiar, cautious, forbearing and hesitating way, slow, but we hope sure,” Douglass now expressed renewed confidence in Lincoln’s integrity. At the same time, he lodged an objection to the delay in the order’s execution which would not take effect until January 1, 1863, with the issuance of the Final Emancipation Proclamation, thus giving the rebels three months’ fair warning. Douglass pointed out that if the justification for the order was military necessity, why then “[n]ecessity is in its nature immediate.” Maybe. But as Douglass argued in December 1862, as he and the nation awaited the decisive announcement, Lincoln himself “was moved by necessity” and that movement had been slow and reluctant: “He reached that point like an ox under the yoke, or a Slave under the lash, not like the uncaged eagle spurning his bondage and soaring in freedom to the skies. His words kindled no enthusiasm. They touched neither justice nor mercy.”

Of course, once the “edict of freedom” came, Douglass rejoiced—and his praise of Lincoln was full-throated: “The President has…made the cause of the slave the cause of the country—welcomed the black man to a place under the star-spangled banner—given him a country, or the hope of a country.” Douglass’s enthusiasm was linked to a major difference between the Preliminary and the Final Proclamation, namely, a paragraph welcoming the freedmen into the armed services of the United States. Douglass grasped the significance of the addition. Liberty was a great good, but what Douglass sought for his people was liberty under equal laws. He wanted “every slave free, and every free man a voter.” Inclusion in the war effort was an essential step in that direction. As he foresaw, whites too were liberated by the Proclamation. Indeed, the ramifications reached beyond even the transfiguration of the nation: “There are certain great national acts, which by their relation to universal principles, properly belong to the whole human family, and Abraham Lincoln’s Proclamation of the 1st of January, 1863, is one of these acts. Henceforth shall that day take rank with the Fourth of July.”

***

Douglass’s increased devotion to the cause took the form of encouraging black enlistments. From his own experience of enslavement, Douglass understood the psychology of courage—how the willingness to risk mere life for a higher conception of life was the foundational virtue for properly political beings. Displays of courage by former slaves would lift the nagging fear of slavishness from their own hearts and lessen the invidious prejudices held by whites. The nation, moreover, would have to acknowledge the debt of honor it owed black soldiers (who, by war’s end, constituted one-fifth of Union forces). In effect, service would create an entitlement to citizenship and suffrage. Certainly, Douglass believed in civil equality as a right; and yet, he knew that, whether fair or not, demonstrated merit was the quickest path to secure one’s rights. His thought on these matters was full of practical good sense. While hopeful about the future, Douglass was acutely aware of the psychological legacies of mastery and enslavement that had to be overcome. Should elements within the nation be intent on maintaining white supremacy, Douglass recommended military experience to blacks for the most pessimistic of reasons: self-defense against white terror. To the Republicans, he advised that black suffrage would be needed if there were to be any chance of dismantling the oligarchic structures of the South.

With his eyes fixed on the status of blacks post-Emancipation, Douglass did all he could not only to recruit black troops, but to achieve equal pay and promotion for them. Yet, when the Confederates began mutilating, slaughtering, and re-enslaving captured colored soldiers, Douglass threatened to suspend his activities. He denounced the president for remaining “as silent as an oyster” regarding Confederate violations of the laws of war and went so far as to pronounce Lincoln equally responsible with Jefferson Davis for the atrocities. Douglass wanted retaliation in kind which Lincoln was loath to authorize. There was always a manly bloody-mindedness in Douglass’s notion of justice. Lincoln, whether more objective or more tender-hearted, could not see the justice in killing men not directly responsible for the abuses. Nonetheless, at the end of July 1863, Lincoln did issue an Order of Retaliation, decreeing the execution of a rebel prisoner for “every soldier of the United States killed in violation of the laws of war.” This severe retribution was never carried out, as more calibrated measures proved successful in restraining Confederate behavior. After his early August interview with the president (their first face-to-face meeting), Douglass was sufficiently reassured to resume his recruitment efforts.

***

The next year brought more ups and downs. Douglass didn’t approve of Lincoln’s plan for reconstruction in Louisiana, viewing its easy terms for re-incorporation within the Union (a loyalty oath sworn by 10% of the state’s 1860 voting population) as too lenient toward secessionist treason. Nor did Douglass see evidence of Lincoln’s commitment to extend the suffrage. Yet, after another interview with Lincoln in October 1864, and with “the bitterly pro-slavery” General George McClellan running on the Democratic ticket as the only electoral alternative, Douglass resolved to work earnestly for Lincoln’s re-election. He acknowledged that he was “now-a-days taking a more practical view of things than formerly.”

That practical turn was rewarded with an inauguration address that was a revelation to Douglass. It was sublime in a way that the Emancipation Proclamation had not been. Douglass marveled in particular at Lincoln’s declaration that God would be a just God were he to insist that “every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword.” Calling the speech a “sacred effort,” Douglass said, “There seemed at the time to be in the man’s soul the united souls of all the Hebrew prophets.” For the next 30 years, Douglass regularly quoted and paraphrased this divine reparations passage. One can imagine what it must have meant to Douglass—a man born into bondage whose entire life was devoted to abolishing slavery and overcoming the damage it did—to have the chief executive of the nation officially acknowledge the depth of the offense of American Slavery, tracing it all the way back through “two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil,” and then proposing that Americans, North and South, unite in understanding “this terrible war, as the woe due to those by whom the offence came.” Douglass understood that Lincoln’s theological interpretation of the war was meant to be reparative in the most profound sense—the discovery of sacrificial ground out of which both sectional and racial reconciliation might grow.

***

The first half of this anthology covers the seven years from 1858 to 1865; the remaining half contains post-assassination selections: eulogies, passages from Douglass’s final autobiography in 1881, and remembrances of Lincoln in various anniversary speeches—the quantity of these is not surprising when you remember that Douglass lived until 1895 and regularly appealed to the memory of Lincoln in order to forward the cause they shared: republican government based on liberty and equal rights. Douglass’s deployment of Lincoln’s character and example underwent subtle shifts, with differing emphases depending on occasion and audience. For example, in his retellings of their personal interactions, Douglass always remarked on Lincoln’s courteous treatment of him, meeting him as an equal with no hint of color prejudice or even color consciousness. He found him “one of the very few white Americans who could converse with a negro without anything like condescension.” And yet, in his 1876 Oration, Douglass, with no reference to their interviews, insisted that “in his prejudices, [Lincoln] was a white man.” Similarly, in the eulogies Douglass delivered in the months immediately after the assassination, he described Lincoln as “emphatically the black man’s President,” whereas in the 1876 Oration, he characterized Lincoln as “pre-eminently the white man’s President.” In December 1865, Douglass gave evidence of Lincoln’s “friendly feeling for the colored race,” whereas in 1876 he spoke of his “unfriendly feeling” toward blacks.

By cherry-picking a few passages (as I have just done), it is easy to overstate the difference between these assessments. For a truer picture, let’s return to the June 1865 eulogy, delivered at Cooper Union. In a paragraph responding to the disgraceful “attempt to exclude colored people from his funeral procession in New York,” Douglass articulated why blacks would wish to join in the outpouring of grief for the slain president: “Abraham Lincoln, while unsurpassed in his devotion, to the welfare of the white race, was also in a sense hitherto without example, emphatically the black man’s President: the first to show any respect for their rights as men.” In other words, Douglass was, from the first, aware of two distinct and racially-specific claims upon the memory of Lincoln: whites were grateful for union; blacks for liberty.

***

This same dualism was present in the 1876 Oration. Worried that the project of federal Reconstruction was being abandoned and that the spirit of the Old South was resurgent, Douglass reworked much of the material in the earlier eulogy, but with greater nuance and circumspection. With whites even less inclined than formerly to make space for black gratitude toward Lincoln (that is, without lessening their own admiration for him), Douglass began by placing heavier stress on Lincoln as “pre-eminently the white man’s President, entirely devoted to the welfare of white men.” Douglass showed how Lincoln’s sharing in their “unfriendly feeling” toward blacks was “one element of his wonderful success in organizing the loyal American people for the tremendous conflict before them.” Douglass argued that Lincoln was correct to prioritize union. In doing his duty to those who elected him, Lincoln acted as a democratic statesman ought. Abolition was, for Lincoln, strictly speaking, secondary. And yet, the two missions turned out to be inseparably connected. It was only through the triumph of the Union that slavery was destroyed. As Douglass explains, Lincoln actually did much more than strike against slavery; his administration dismantled many forms of anti-black “prejudice and proscription.” By the close of the speech, whatever the extent of that earlier “unfriendly feeling”—and whether sincerely felt or politically affected—Douglass is able to embrace Lincoln as “our friend and liberator.” Beginning from the phenomenon of racially-identified gratitude toward Lincoln, Douglass structures his speech to move his audience toward a new possibility: Individuals of both races can understand and celebrate Lincoln’s twin mission. Blacks can appreciate a Union dedicated to the proposition of human equality; whites can appreciate black liberation and the nation’s deliverance from wrongdoing; all can benefit from fidelity to the Constitution and laws.

Douglass was a master of the art of memorialization for political purposes. In paying tribute to Lincoln’s statesmanship, he displayed his own statesmanship. With its sophisticated analysis and attentiveness to the limits set by public opinion, the 1876 Oration stands as his greatest and most Lincolnian speech. Of course, just as no single speech by Lincoln could avert the war, or achieve a new birth of freedom, or inaugurate charity for all, no single speech by Douglass, summoning and shaping the memory of Lincoln, could foster a spirit of citizen friendship and a unified national consciousness. His lifetime of editorializing and speechifying, however, surely had transformative effects, preparing blacks for civic participation and preparing whites to accept that new dispensation. The words of Frederick Douglass, especially those about Abraham Lincoln gathered here in Measuring the Man, still carry redemptive power.