IN THIS ISSUE:

- Time to Adapt and Plan for Weather Events, Climate Change Aside

- Climate Science Faces a Crisis of Accuracy and Confidence

- Deaths and Hurricanes Haven’t Followed the Climate Change Script in 2025

Time to Adapt and Plan for Weather Events, Climate Change Aside

A glimmer of truth seeped out through the pages of The New York Times (NYT) recently, in a story examining how “unprepared” large parts of the nation are in the face of natural disasters. Although it is impossible to predict the exact dates of such disasters well in advance, we certainly know that they are more likely to strike in certain places, based on history, geography, and climate. Of course, this wouldn’t be an NYT story if it didn’t have a heaping dose of unwarranted climate change misdirection mixed in.

The story, written by David Wallace-Wells, briefly discusses multiple recent extreme-weather events that resulted in billions of dollars in damage and hundreds of deaths. These include the 2023 Hawai’ian Lahaina wildfires and those in Los Angeles in 2024, and the flooding in the Texas hill country last month, in Libya in 2023, and in Porto Alegre, Brazil and Ashville, North Carolina in 2024, with brief mentions of recent hurricane strikes.

These events were tragic, and, as Wallace-Wells points out, the results were largely preventable. The places where the floods and fires occurred had previously experienced large floods and fires multiple times. The common tragedy is, with our current understanding of the areas’ histories of extreme weather events and the modern ability to harden infrastructure and manage resources, including improved housing location, relatively little was done after previous extreme weather events to prevent these new tragedies from occurring. In fact, often the actions taken, such as more people moving to disaster-prone areas, made the results of the recent events even worse.

The scale of the harm and the loss of lives could have been drastically reduced if planners and bureaucrats had instituted warning measures, built better infrastructure to handle water, not incentivized rebuilding in known flood zones, managed lands to reduce the fuel load for fires, and improved early access for fighting them. There is enough blame to go around at the national, regional, and local government level in each country, but what Wallace-Wells clearly shows is that much of the harm caused by these events was entirely preventable based on existing knowledge and present technology.

No place is a climate haven. Every place gets hit with extreme weather at one time or another, but history shows some locations are more prone to certain types of extreme weather events or natural disasters than others, experiencing them with some regularity. With that understood, better planning and decisions about where to live, how to manage lands, and what types of infrastructure should be built where, should be undertaken before the next flood, wildfire, or hurricane strikes, or in the case of ongoing sea-level rise, planning for the inevitable until the next glacial period comes.

Although Wallace-Wells ties the extremity of some of the recent weather to climate change, despite there being no long-term trends suggesting such a connection, he does have the decency or honesty to admit these types of events occur with some regularity in some places more than others, regardless of climate change, so we should be better prepared. Wallace-Wells writes,

[F]or all its exceptional brutality, the Guadalupe River disaster in Texas last weekend was also a familiar-seeming one. … The downpour that produced the Texas flood was called a 500-year storm, but flash floods are not unknown in the area, which is sometimes known as Flash Flood Alley and where officials considered—and rejected—an early-warning system just eight years ago, after the Guadalupe flooded catastrophically. The river has breached its banks more than a dozen times since 1978.

In fact, the same is broadly true of Valencia, where a 1957 flood killed at least 80, and in Pôrto Alegre, where the 1941 floods long cast a shadow over local memories, and indeed in Asheville, N.C., too, where a 1916 flood killed 80. … None of these are places where flooding disaster was unthinkable—only places where too many people chose not to think too hard about it, and officials were only too happy to pass the buck. …

We may want to focus on the risks of warming to come, but as the eminent climate scientist Michael Oppenheimer likes to emphasize, we’re not all that well adapted to the climate we have now. That is what it means to be overwhelmed, again and again, by weather horror—the standards for safety and security we set for ourselves, in the wealthy modern world, are breached pretty regularly by weather events we should be able to manage much better.

The author of a discussion of the NYT piece at Climate Discussion Nexus focuses most of his attention on critiquing the unfounded, demonstrably flawed assertions tying the disasters to human fossil-fuel emissions. I understand the author’s motives and am sympathetic to his criticism. Wallace-Wells commits untenable mental contortions and makes unfounded or even contradictory statements to attribute each of the events to long-term climate change to some extent. But for me, that’s to be expected. I would have been surprised if a writer for the NYT didn’t try to link the weather disasters to climate change. After all, we at The Heartland Institute maintain a website dedicated to debunking “news” stories posted on a daily basis that falsely claim climate change is making some “X” worse or causing some “Y” to become more frequent or intense, or that it is leading to more death, starvation, disease, or immigration. Data shows it just ain’t so, but the media doesn’t care.

With that in mind, I’ll take some hope from the fact that most of the NYT piece didn’t focus on presenting climate change as the sole or even main cause of the disasters discussed, but rather placed the blame firmly where it lies: on human decisions and actions grounded in wishful thinking, denial, or short memories (it can’t happen to me); and poor planning for such future events; all leading to inadequate responses. This is due in part to politicians wasting time and scarce resources playing the blame game about who was (more) responsible for the last tragedy instead of quickly moving to cooperate to lessen the harm when extreme whether strikes again, as it inevitably will, in the future.

Sources: The New York Times; Climate Discussion Nexus, Climate Realism

Climate Science Faces a Crisis of Accuracy and Confidence

A recent study published in Nature warns climate science is facing a crisis of the scientists’ own making, which may require rethinking or at least modifying the narrative that human-caused climate change poses an existential threat or an environmental apocalypse.

Although some forecasts or predictions of climate scientists which would tend to confirm the doomist narrative have come to pass or are proving true, many, many other such projections and claims of disaster have failed to be confirmed and show no signs of proving out in the foreseeable future, the study’s authors write. This is leading to a crisis of confidence in climate science among the wider public, but it should also lead the practitioners to become more open to countervailing evidence and be more cautious in their claims while preparing for the possible necessity of a paradigm shift.

The study’s authors write,

As Earth warms, regional climate signals are accumulating. Some signals, for example, land warming more than the ocean and the Arctic warming the most, were expected and successfully predicted. Underlying this success was the application of physical laws under the assumption that large and small spatial scales are well separated. This established what we call the standard approach, climate science’s dominant paradigm. With additional warming, however, discrepancies between real-world signals and expectations based on this standard approach are piling up, especially at regional scales.

Philosophers of science characterize situations where accumulating discrepancies (anomalies) and disruptions lead to a loss of confidence in the dominant paradigm as a ‘crisis.’

Even among climate scientists, it is perhaps not fully appreciated how simple ideas and the assumptions common to these ideas underpin this consensus. … [D]iscrepancies are, in fact, accumulating.

Commenting on the looming crisis and what it might mean, astrophysicist David Milliband notes it is common in science for observations that don’t fit the dominant or emerging paradigm to be discovered, often only to be explained away. However, when such discrepancies mount, it raises serious concerns about the prevailing theory, questions that need addressing in a systematic way, perhaps forcing the theory to be overturned or at the very least meaningfully modified.

The researchers believe the problem with the dominant paradigm stems from a flawed understanding of the climate system that assumes it is simpler than it is, dictated on a macro and to some extent micro scale by laws of physics alone.

“Such an understanding allows relatively straightforward explanation of climate change and to build climate models, but [it] seems to be belied by the fact that both local, regional, and larger factors aren’t captured in that understanding of the climate system, yet they have profound effects on measured changes or outcomes, falsifying projections repeatedly,” writes Miliband in summarizing the study’s findings.

There is a second “crisis” looming for climate alarmists: not the crisis in science raising the specter of the end of enforced consensus around a single disaster, but rather the crisis of trust in scientists in general and climate science in particular, by the general public. This problem arises because, as Ella Al-Shamahi, presenter of the BBC’s science series Human, says in The Times, science in academia is dominated by people on the political and social left. By a huge margin, scientists are progressive (like Al-Shamahi herself) or liberal, with any academics on the political right being silenced or self-silencing on campus, in the classroom, and in professional journals.

The academic left’s dominance shapes the research questions being addressed, and it limits the acceptable range of topics. It also suppresses the publication or coverage of outcomes inconvenient to the “climate change causes everything bad” narrative, in part by ensuring some questions or doubts are never raised in the first place.

The Times writer quotes Al-Shamahi at length, writing,

She said diversity is essential in science. “I mean that in its totality,” she said. “It is not just the people who look like me who need to have more of a place here. It also needs to be people who think like me—and the people who don’t think like me. Where are the deeply, deeply devout religious scientists? Where are the right-wing scientists? If all our biases are not in the room it leads to worse science outcomes.”

“Inclusivity is really important to me,” she said. “Science belongs to each and every one of us. So I defend the right of those who I disagree with to exist—even if don’t like their ideas. They represent the ideas of so many people. We can criticise them. We can say we don’t like their ideas. But we should let them voice those ideas.”

Suppression of unpopular ideas and forcing of groupthink in academia and at research centers hurts scientific progress and the public’s trust in science.

Source: Nature; Net Zero Watch; The Times (UK)

Deaths and Hurricanes Haven’t Followed the Climate Change Script in 2025

The year 2025 has been throwing cold water on the climate scare thus far. Although the numbers will undoubtedly change, deaths from extreme weather events and other natural disasters are well below the norm for midyear, so far below that it’s doubtful they will reach anywhere near the single-year average. In addition, although the busiest part of the Atlantic hurricane season still lies before us, the hurricane numbers are running below normal thus far in the Atlantic and in other basins, forcing the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to revise its hurricane forecast downward. NOAA still predicts an above-average season, but only slightly so, with its estimated number of named storms and major hurricanes being revised downward from NOAA’s May preseason forecast.

“While June and July tropical cyclone activity does not say much about what happens in the rest of the year, summer 2025’s lack of anything like last year’s Category 5 Hurricane Beryl is a strong hint that this season is not heading for an extreme hyperactive outcome of, say, doubling normal activity,” noted the Tallahassee Democrat in commenting on the slow start of 2025’s hurricane season.

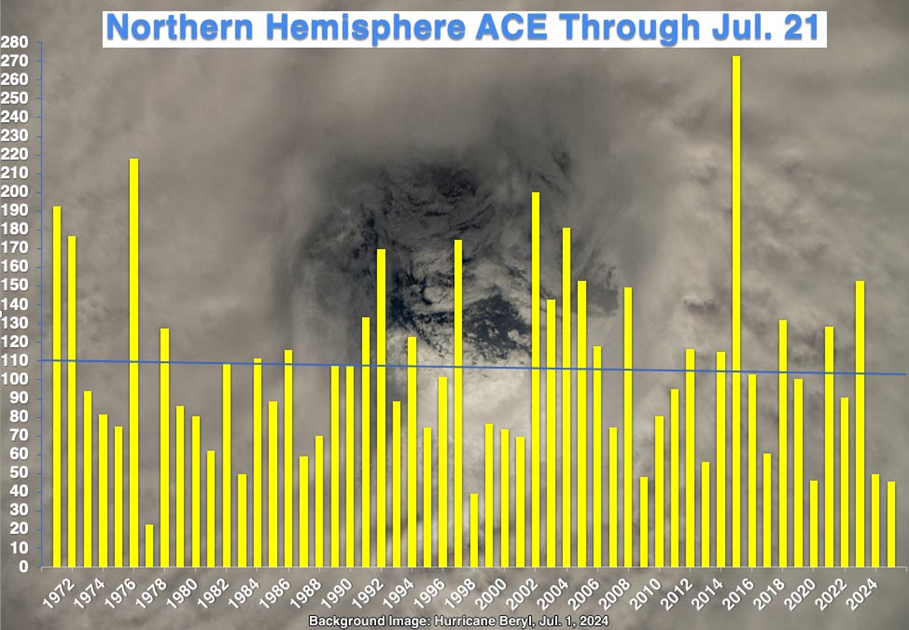

It is not just the Atlantic hurricane basin that is experiencing below-normal tropical storm activity this year. The title of a July 21 story posted on Yale Climate Connections (YCC) describes the underwhelming, surprising to forecasters, state of hurricane activity across the Northern Hemisphere: “A weird lack of Northern Hemisphere tropical cyclones so far in 2025.”

“It’s been one of the least active years on record for tropical cyclones in the Northern Hemisphere,” reports YCC.

All the Northern Hemisphere storm-producing regions have been calmer than average this year, the YCC article states:

It’s not just the Atlantic that’s been quiet. Each of the four basins of the Northern Hemisphere that generate tropical cyclones—the Atlantic, Northeast Pacific, Northwest Pacific, and North Indian Oceans—is now running below average on accumulated cyclone energy, or ACE, a function of peak wind speeds and storm longevity. For the hemisphere as a whole, the total ACE to date is the third-lowest in records dating back more than half a century.

YCC provides a helpful graph:

Figure 1. Accumulated cyclone energy for all tropical cyclones in the Northern Hemisphere for each year from January 1 through July 21, 1971-2025. (Image credit: Data courtesy Colorado State University)

We can pray the below-normal trend continues even as we can expect an increase in activity over the next three months.

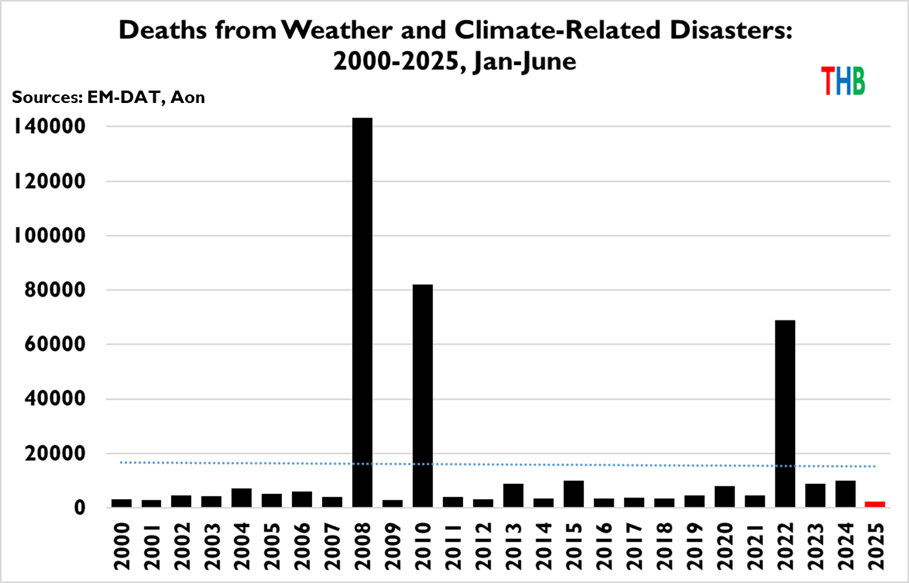

It’s not just tropical storm/hurricane activity and strength that are running below expectations. An even more direct metric of human well-being in the face of dire weather conditions, deaths due to extreme weather and natural disasters, is running far below the norm for midyear.

Writing on his Substack channel, The Honest Broker, long-time climate alarmist gadfly Roger Pielke Jr., Ph.D., noted,

In the annals of history, the first half of 2025 will be remembered for many things. I’d venture that very few are aware of one of the most momentous achievements in human history occurred in the past six months.

In fact, there is an organized effort to keep you from understanding this achievement. Before getting to that effort, let’s first take a look at some remarkable new data on the impacts of weather on people.

. . . the Aon Global Catastrophe Recap, First Half ((1H) of 2025 . . . [reported that only] 7,700 people were killed due to natural disasters during the first half of 2025, which is well below the 21st-century average of 37,250. Majority of the deaths (5,456) occurred as a result of the earthquake in Myanmar.

That means that ~2,200 people worldwide died in catastrophes related to extreme weather events during the first six months of the year.

On the one hand, ~2,200 deaths are a lot and every loss of life is tragic. On the other hand, in the context of historical losses related to weather extreme, on a planet of 8.2 billion people, ~2,200 deaths is incredibly low. Historically low, in fact.

It is likely that the first half of 2025 has seen the fewest deaths related to extreme weather of any half year in recorded human history.

Pielke provides an informative graph:

Sources: EM-DAT (black, 2000-2024), Aon (red, 2025).

Although the hurricane season may still produce an above-average number of storms, it would be hard to imagine the number of weather-related deaths catching up to the overall average for the year—and thank the Lord for that! Despite weather not becoming observably more extreme, weather-related disaster costs are rising because more people are moving into areas prone to natural disasters. By contrast, deaths from these events are down, not due to luck but due to improved infrastructure, early warning, and disaster recovery systems. Societies are becoming wealthier, and as they are doing so they are taking steps to adapt to extreme weather, regardless of any long-term changes in climate.

The purported existential threat that climate change poses to human existence isn’t playing out in real life. Fewer people are dying from the types of extreme weather events climate alarmists routinely blame on climate change, and hurricanes aren’t coming earlier and aren’t generating more power.

What other discrepancies between the narrative of catastrophic climate change and reality will be forthcoming?

Sources: The Honest Broker; Tallahassee Democrat; Yale Climate Connections