Update (1500ET): In a blow for Republicans’ ‘crypto week’, a House procedural vote on the crypto measures failed to pass.

The House voted 196-222 against taking a step needed to begin consideration of three industry-backed bills including one on stablecoin regulation.

House conservatives have previously blocked procedural steps to show discontent.

Republican “no” votes included Reps. Ann Paulina Luna (Fla.), Scott Perry (Pa.), Chip Roy (Texas), Victoria Spartz (Ind.), Michael Cloud (Texas), Andrew Clyde (Ga.), Eli Crane (Ariz.), Andy Harris (Md.), Marjorie Taylor Greene (Ga.), Tim Burchett (Tenn.) and Andy Biggs (Ariz.).

It wasn’t immediately clear what impact the vote would have on the legislation, which still could be considered if leaders muster sufficient support.

Johnson told reporters after the vote that the hardline critics want to link the cryptocurrency bills into one product, which is why they torpedoed the procedural vote:

“Some members who really, really want to emphasize the House‘s product, as you know, Clarity Act, and the Anti-CBDC Act,” Johnson said.

“We have our bills as well, they want to push that and merge that together. We’re trying to work with the White House and with our Senate partners on this. I think everybody is insistent that we’re gonna do all three, but some of these guys insist that it needs to be all in one package.”

The House can take up the procedural vote again, but the timing is now unclear.

* * *

Standard Chartered’s Global head of digital assets research, Geoffrey Kendricks, was surprised last week that, after meeting with a combination of crypto-natives, Bitcoin miners, leveraged and real money funds, digital asset tokenisers and policy makers; despite fresh all-time highs in bitcoin, 90% of the conversations were spent talking about stablecoins.

Interest in stablecoins in the US is surging ahead of the GENIUS Act passing into law (possibly as soon as this week).

As such, discussion centered on implications for UST issuance and eventually curve shape, USD direction, US policy surrounding payments networks, and the potential for stablecoin adoption to lead to financial-stability concerns in selected emerging markets.

In terms of how large the stablecoin market needs to be to unleash those second-order effects, discussions homed in on USD 750bn (current market size: USD 240bn).

That would likely be towards end-2026, by which time clients think that stablecoin issuance will have broadened significantly (in the wake of the GENIUS Act) to include relatively large offerings by banks and perhaps even small offerings by local municipalities.

On the Digital Asset Market Clarity Act, the consensus seems to be that it will pass by late September/early October, which is sooner than I had expected. This act may have implications for decentralised finance and the tokenisation of real-world assets.

Implications for emerging markets

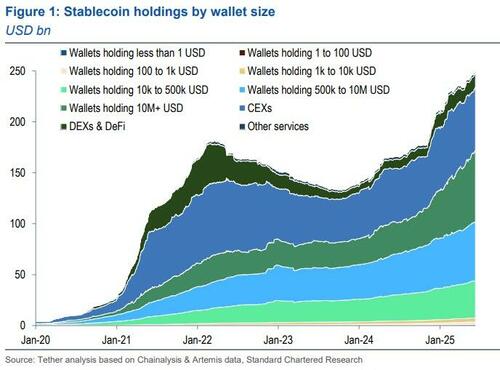

Stablecoin discussions focused mostly on practical considerations surrounding stablecoin adoption, including both planned and unintentional outcomes of such, as well as potential feedback loops to existing traditional finance (TradFi) assets. The starting point of such discussions was that currently, large wallets and centralised exchanges (CEXs) together account for 90% of all stablecoins. Wallets greater than USD 10mn account for 28%, wallets of USD 500k to USD 10mn account for 23% and wallets of USD 10k to USD 500k account for 15%. CEXs account for a further 25% (Figure 1).

Further, the dominance of large wallets has increased during the last three years. During the decentralised finance (DeFi) boom of 2021, CEX holdings dominated, followed by decentralised exchanges (DEXs) and DeFi. While trading on/off ramp remains important for digital assets – albeit more in CEXs than DEXs and DeFi at present – other uses for stablecoins are now becoming much more important.

‘Other uses’ of stablecoins can be split into store of wealth and transactional purposes. So far, store of wealth dominates (there is no widespread need to hold such large amounts in a wallet for transactional purposes). This store-of-wealth rationale is that savings that seek access to a USD bank account (presumably in emerging markets) do so via stablecoins. Indeed, individuals who need to protect their assets in a liquid, trustworthy form are using stablecoins as a secure store of wealth. The requirement for such individuals is return of capital, not return on capital.

The immediate implication of using stablecoins in this way is that the total assumed size of emerging-market demand for stablecoins (across both store of value and transactional uses) may be higher than I had previously assumed.

The next implication is that if large amounts of savings are leaving emerging markets (note: it is impossible to tell exactly where the money is coming from) then those emerging markets that need USD liquidity to maintain fixed exchange rates, capital controls and assist the local banking sector may at some stage find each of these more difficult to manage.

Financial stability issues may ensue.

Implications for developed markets

In developed markets, a useful starting point is that after GENIUS passes, the initial use case will likely be transactional by both developed market corporate treasury functions as well as semi-financial firms that would benefit from the core benefits of stablecoins – they are becoming faster, cheaper and more secure than traditional payments methods.

While the emerging markets’ use of stablecoins may be greater than I had expected (all of which should create new demand for stablecoin reserves, i.e., T-bills), there was some discussion about the amount of reserves required for developed markets’ stablecoin use.

Specifically, the uncertainty centres on two points.

-

First, to what degree will corporates’ stablecoin use (stablecoin require 100% reserve backing) replace their current cash holdings that are parked in off-chain money market funds (i.e., T-bills)? This question requires further analysis. My initial view is that at a minimum, the overall financial payments system will transition from one of bank credit creation (which requires low asset backing) to one of stablecoin use (which requires 100% backing). This implies a large amount of fresh T-bill demand from developed markets, but the exact amount is unknown.

-

The second uncertainty, which also applies to emerging market transactional use cases, has to do with velocity of stablecoins. As more transactional uses emerge, velocity will increase; the question is by how much? The answer will determine how many stablecoins are ultimately needed and, therefore, the extent of fresh T-bill demand.

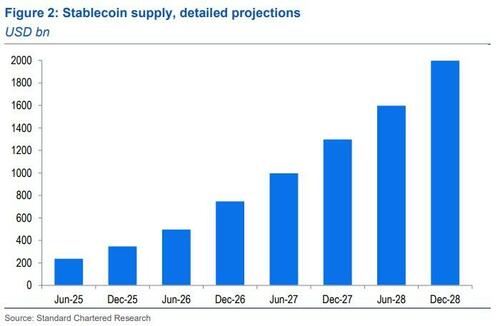

To sum up my view on these points, in my previous report I estimated USD 1.6tn of fresh T-bill demand by the end of 2028; but the confidence interval in both directions (more or less T-bill demand) is, by definition, wide.

Another developed market point that was discussed was how prolific new stablecoin issuers would be after GENIUS passes.

Some argued that the incumbents (USDT and USDC) would likely be most prolific, at least for a while. However, others believed that the issue size of new issuers (banks) may become larger than I thought and that even municipalities may issue their own stablecoins (implying broader issuance than I thought).

How big do stablecoins need to be to have TradFi implications?

At some point the stablecoin market will likely become so large that it starts to have implications for TradFi assets and policies.

In the US, once the stablecoin market gets to a certain size, the amount of T-bills required to back stablecoins will likely require a shift in planned issuance across the curve towards more T-bill issuance, less longer-tenor issuance.

This potentially has implications for the shape of the US Treasury yield curve and demand for USD assets (and hence the USD).

Discussions tended to focus on a level where USD 1tn is in sight, somewhere around USD 750bn. Figure 2 implies that this will be towards the end of 2026.

In terms of broader US policies around financial stability, the same level came up a number of times as being when the stablecoin sector would become systemically important and hence in need of macro-prudential measures. Discussions then also focused on regulatory challenges of non-banks having some control over the payments system as a whole. Questions around money supply control and hence transmission of monetary policy were also raised.

Clarity Act

The Digital Asset Market Clarity Act was introduced in the US House of Representatives in May 2025. It aims to create a regulatory framework for digital assets and digital commodities. My impression is that the administration is focused on late September/early October for the Clarity Act to pass into law. This is earlier than I had previously assumed (year-end) and would be a positive surprise for the asset class.

There will also be specific implications for the tokenisation market. I had previously argued that the initial winners in the tokenisation space would be those that generate on-chain liquidity for assets which are illiquid off-chain (see RWA tokenisation – A growth opportunity). However, meetings on this suggested that if DeFi can be unleashed following the Clarity Act (specifically if tokenised assets can be deposited on AAVE) then tokenised assets expansion may be broader, and might include tokenised public equities, for example (as DeFi leverage capabilities of such assets would be significant).

Loading…