When I began my work at AEI seven years ago, my first report was entitled, STEM Without Fruit: How Noncognitive Skills Improve Workforce Outcomes. The underlying thesis of that report was that we had gone too far in promoting education, training, and credentials—including college degrees—that focused on science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM), when employers were clearly signaling that soft and noncognitive skills were the attributes most in demand by employers.

Here are the opening bullets of that report:

- Labor market data and employer feedback suggest that the emphasis on STEM in workforce development is obscuring deeper, widespread challenges to employability relating to noncognitive skills associated with persistence and character, particularly for middle-skill occupations.

- Employers report a need for employees with these skills and place a higher value on them than on job-specific skills.

- Noncognitive skills (e.g., listening, problem-solving, teamwork, integrity, and dependability) are rooted in infancy and early childhood experience and develop across the life cycle.

- Especially for low-income families and communities, interventions that strengthen family formation, improve early childhood education, and support adults in combining noncognitive and technical skill training are key to improving long-term labor market outcomes.

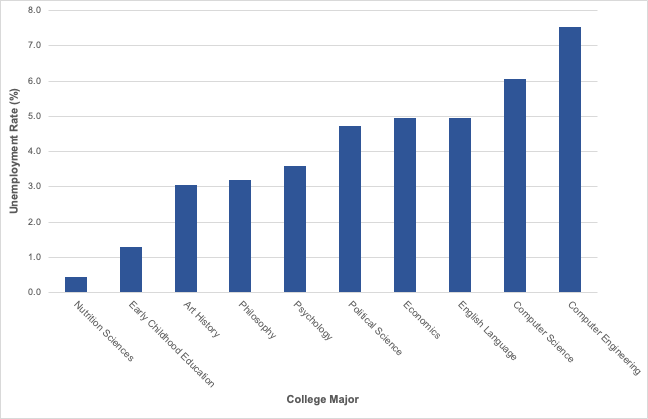

What I did not know, and could not foresee, was how the emergence of generative artificial intelligence would accelerate the “deskilling” of technical work and exacerbate the “brittleness” of technical education while increasing demand for the so-called “soft” degrees—which the zeitgeist tells us are the least useful for finding jobs. The most recent figures from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York are startling: Unemployment among people with computer engineering and computer science degrees is at least twice as high as that of graduates in fields like psychology, philosophy, art history and early childhood education.

Figure 1. Which Majors Face the Toughest Job Market?

As with all economic figures, there are nuances. Although the unemployment rate for computer scientists and engineers is high, their underemployment rate (i.e., the share not working in roles that fully utilize their skills) is significantly lower than that of liberal arts majors. For example, the underemployment rate for computer engineering graduates is only 16.5 percent, compared to 46.8 percent for nutrition sciences graduates. This suggests that, while nontechnical majors may be more likely to be employed, they may also be more likely to be taking jobs that are unrelated to the degrees they received.

Wages are also an issue. There are also still significant starting wage gaps between technical and nontechnical jobs. Early-career computer engineers make $80,000, compared to $54,000 for early-career nutrition scientists. Though if you have a technical degree, but can’t find a job in your field, what you could be making may not be of much comfort. Moreover, the disparities between technical and nontechnical careers tend to narrow over time, with humanities majors closing a significant amount of the gap while pay for technical positions levels off.

Regardless, the story of AI and the skills we need in order to adapt is becoming clearer. Resilience (and relevance) in today’s job market will come from developing complementary skills—those that AI cannot replace easily: emotional intelligence, communication, adaptability, leadership, and ethical reasoning. These human attributes, when paired with baseline technical fluency, create a durable skill set that allows workers to prosper through technological change.

Those who remain focused on acquiring narrow technical degrees and certifications should be aware of the way skill demands are shifting. As any psychology major will tell you, the dreaded majors question, “So what are you gonna do with that?” can be hard to answer.

The post Degrees of Risk: STEM Is Bearing Less Fruit appeared first on American Enterprise Institute – AEI.