Editorial note: This essay originally appeared at The Giving Review.

Politicization rarely benefits any institution. Consider business, labor, academia, philanthropy, journalism, entertainment, athletics, medicine, and law. Add “Big” to any of these—as many, plausibly, do—and you’ll find the attitudinal adjective often reflects their politicization: Big Business, Big Labor, Big Philanthropy, Big Law. Or just call them “elite” or “establishment.”

We’re living through healthy reactions against Bigness, elitism, and the establishment. They’re driven by populist impulses shared by conservatives and progressives alike. Notably, they’re perhaps expressed most strongly throughreal politics. In our democratic republic, after all, politics remains one of the few ways for populist sentiment to translate into reform by elected policymakers. In effect, there’s now a politics against politicization itself.

Big Labor and Big Philanthropy are major pillars of today’s politicized progressive left—often bigger, more liberal, and more entangled with government than others. They deserve special attention.

Labor unions and charities have each been and can each be conceived as admirable examples of Tocquevillian civil society at its most vibrant. That conception of them, however, has become strained—in the case of unions, by the policy-nurtured coercive nature of membership in them, and in the case of charity, by the also-policy-aided redefinition of its original, plain-English meaning beyond anything Alexis de Tocqueville would recognize. In the limited discourse about philanthropy, “civil society” seems too often automatically and lazily conflated with “nonprofit sector,” a term arising from the tax code. Tocqueville didn’t use “§” in his writings describing and explaining America; the Internal Revenue Code (IRC) came much later.

Populists of differing underlying wordviews have long been uncomfortable with the largest labor unions and tax-exempt charitable nonprofit organizations, including the richest grantmaking foundations, and their self-protective and -promotional political activities. These activities are at least in tension, often in conflict, with most everyday understandings of the common good.

Populist conservatives have been among those with this discomfort, of course. They’re newly politically and ideologically ascendant, and they’re playing a larger role in government. It’s thus important that any attempted depoliticizations of labor and charity taking form at their behest be informed by history, knowledge, and intelligent analysis.

There are similarities and differences between politicization in the specific contexts of labor and charity. Comparing and contrasting attempted and proposed depoliticizations of them would benefit potential future federal-policy reform in pursuit of the wider public interest.

Beck

CWA could still use Beck’s—as all unions could still use any nonmembers’—agency fees for lobbying, voter education, public-education campaigns, and donations to organizations that advance the unions’ political agenda . . .

Begin with maintenance worker Harry Beck—the named respondent in 1988’s momentous, for conservatives, Communications Workers of America v. Beck U.S. Supreme Court case. Beck was a member of and even worked as an organizer for the Communications Workers of America (CWA), a big labor union. He strongly objected to CWA’s institutional financial support, derived from dues he paid to the union, of the 1968 presidential campaign of Vice President Humbert Humphrey and the 1970 re-election campaign of U.S. Sen. Joseph Tyding of Maryland—each of which Beck individually opposed.

He sought a refund from CWA for the portion of his dues spent on this type of direct political support, and he challenged the union’s accounting to determine what was spent on it versus collective bargaining. This opposition led to his early-1970s resignation from CWA.

Even as a nonmember, as a condition of employment, Beck still had to be what’s known as an “agency-fee” payer to the union. His agency fees, $10/month at the time, would be limited to CWA serving as the negotiating agent with his private-sector employer, then the Chesapeake & Potomac Telephone Company, regarding the terms and conditions of employment. Those payments could not be used by the union to support any political candidates, political parties, or federal election campaigns.

So: no “free-riding” by nonmembers on the union’s “collective bargaining” or “representational” activities; no union-forced payment to candidates, parties, and campaigns either, however, by agency-fee payers who oppose those candidates, parties, and campaigns.

CWA could still use Beck’s—as all unions could still use any nonmembers’—agency fees for lobbying, voter education, public-education campaigns, and donations to organizations that advance the unions’ political agenda, though. All of these uses are unrelated to collective-bargaining representation, too, of course.

So: still no “free-riding” by nonmembers on the union’s representation, but union-forced payment for lobbying, voter education, public education, and organizations to further the union’s political agenda could still be chargeable to the nonmembers’ mandatorily paid agency fees.

Beck

Beck was thus justifiably considered a major legal victory, with known political ramifications, by and for conservatives . . .

Beck understandably opposed these uses, as well. In 1976, with 19 others, he sued CWA to prevent them. The lawsuit argued that CWA’s use of agency fees for anything other than collective-bargaining or workplace representation violated the rights accorded them by both the First Amendment and the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) of 1935, as amended by the Labor Management Relations Act, or Taft-Hartley Act, of 1947.

Big Labor’s power in a private workplace like Beck’s derives largely from the NLRA. The statute applies to most private-sector employers and employees, but does not apply to public-sector employers, employers of agricultural workers, or employers of interstate railroads and airlines. Its stated purpose is to “restor[e] equality of bargaining power between employers and employees,” considered a common good by those who voted to pass it. In pursuit of this good, it accorded an assortment of benefits to labor unions, in addition to already enjoying the benefit of tax-exempt status under IRC § 501(c)(5). When Beck’s case finally was decided in 1988, the Supreme Court held for him and his colleagues—not on any Constitutional, but rather on the NLRA’s statutory, grounds.

The ’88 Beck ruling was consistent with—essentially, extended—the Court’s Abood v. Detroit Board of Education 11 years prior. In 1977, Abood permitted unions in the public sector to collect agency fees from nonmembers under the relevant Michigan statute, provided they were not used for political or ideological purposes unrelated to collective bargaining. Beck applied this Abood principle to the private-sector context under NLRA, while Abood focused on public-sector unions’ bargaining with government employers and under different statutes.

Specifically—as well-delineated by American Compass policy advisor Daniel Kishi in a July 2025 paper, “Organized Labor’s Democratic Deficit”—in the wake of Beck and its interpretation of union and employee rights under the NLRA, only the following union expenditures are currently “chargeable” to all private-sector employees in either union dues or compulsory agency fees:

- Collective bargaining negotiations

- Grievance handling and arbitration

- Representation during workplace disputes

- Internal union governance directly related to collective bargaining and representational functions

The following union expenses are “nonchargeable” to nonmember agency-fee payers who assert their “Beck rights” to object to and not have to pay them, according to Kishi’s overview:

- Ideological or political advocacy not directly related to collective bargaining or representation

- Communications advocating broad ideological or political positions

- Lobbying on political issues or legislation unrelated to collective bargaining

- Supporting ballot initiatives not directly related to collective bargaining

- Campaigns to organize new workers

That’s a lot of necessary delineation.

For the following types of spending, Kishi notes, unions must use a political-action committee—individual contributions to which are voluntary:

- Contributions to political candidates

- Contributions to political parties

- Direct financial support for election campaigns

- Express advocacy explicitly supporting or opposing candidates (e.g., political ads/mailings)

Beck was thus justifiably considered a major legal victory, with known political ramifications, by and for conservatives—onetime labor organizer Beck among them.

Janus

In the public-sector context, in other words, there’s no need to delineate among any degrees of necessary or desired depoliticization; it’s all political . . .

Two decades post-Beck, in its landmark 2018 Janus v. American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees(AFSCME) decision, the Court held, 5-4, that public employees cannot be required to pay any dues or fees to unions at all—even for collective-bargaining and workplace-representation purposes—if they do not consent. It explicitly overrules Abood, which allowed for the collection of nonmembers’ agency fees for these purposes. Unlike Beck, Janus was decided on Constitutional, rather than statutory, grounds—essentially because the First Amendment constrains state actors, which is what public employers by definition are, and because private-sector unions operate under the NLRA and not state law.

Under the Illinois Public Labor Relations Act at issue in Janus, “public employees are forced to subsidize a union, even if they choose not to join and strongly object to the positions the union takes in collective bargaining and related activities,” begins Justice Samuel Alito’s opinion for the Court. “We conclude that this arrangement violates the free speech rights of nonmembers by compelling them to subsidize private speech on matters of substantial public concern.”

Later in Janus, Alito writes, “Compelling a person to subsidize the speech of other private speakers raises … First Amendment concerns.” As for the nature of that compelled, subsidized speech in the private-sector context of Beck and the public-sector one of Abood and Janus, he writes later in Janus,

The challengers in Abood argued that collective bargaining with a government employer, unlike collective bargaining in the private sector, involves “inherently ‘political’” speech. … The Court did not dispute that characterization, and in fact conceded that “decisionmaking by a public employer is above all a political process’ driven more by policy concerns than economic ones.”

The Abood Court, Alito continues,

asserted that public employees do not have “weightier First Amendment interest[s]” against compelled speech than do private employees. … That missed the point. Assuming for the sake of argument that the First Amendment applies at all to private-sector agency-shop arrangements, the individual interests at stake still differ. “In the public sector, core issues such as wages, pensions, and benefits are important political issues, but that is generally not so in the private sector.”

(All citations omitted; emphasis, brackets in original.)

In the public-sector context, in other words, there’s no need to delineate among any degrees of necessary or desired depoliticization; it’s all political, and since compelled subsidization, unconstitutional.

Responding to AFSCME’s argument that agency fees are necessary to prevent the “free-rider” problem, Alito notes that the case’s “[p]etitioner strenuously objects to this free-rider label. He argues that he is not a free rider on a bus headed for a destination that he wishes to reach but is more like a person shanghaied for an unwanted voyage.”

Alito continues, “Whichever description fits the majority of public employees who would not subsidize a union if given the option, avoiding free riders is not a compelling interest” and free-rider arguments are generally insufficient to overcome First Amendment objections. “To hold otherwise across the board would have startling consequences. Many private groups speak out with the objective of obtaining government action that will have the effect of benefiting nonmembers. May all those who are thought to benefit from such efforts be compelled to subsidize this speech?”

Like Beck, Janus was also justifiably considered a major legal victory, with known political ramifications, by and for conservatives. It takes Beck’s restriction on compelled fees further by forbidding all compelled subsidization of collective bargaining in the public sector—not just that for purely political spending outside collective bargaining or workplace representation, whether it comes in the form of dues or agency fees.

After Janus, Beck rights now need only be exercised against Big Labor in the private sector. In that sector, however, they can only be exercised by nonmember, agency-fee-paying Beck objectors to unions’ politicization. Existing private-sector union members who object to the use of their dues for anything other than collective-bargaining or workplace representation have to resign their membership to assert those Beck rights. Even then, of course, unions make it as logistically and administratively difficult as possible to exercise them.

Post-Janus, proposed further depoliticization of unions

As part of [Kishi’s] suggestion, “Unions would be legally required to meaningfully consult with their members through polling or other direct engagement before endorsing candidates or engaging in political advocacy.”

Since Janus, some have argued that its reasoning should be judicially extended to private-sector unionized workplaces, too, taking the position that enough “state action” exists even in the private context to enable similar First Amendment protections against compelled subsidization for private employees. This would seem quite challenging a route on which to pursue such an extension, mostly because of Alito’s language parsing the different characteristics of the inherently politicized public- and apparently not as politicized private-sector contexts in Janus.

There have always been various proposed legislative expansions of all kinds to the rights of employees, as well—perhaps most recently including in this depoliticization context from Kishi of the intellectually lively, increasingly influential, populist-conservative American Compass. “Congress should codify and expand Beck rights to ensure union members can object to funding political and ideological activities without resigning their union membership or losing representation benefits,” he recommends in the “Organized Labor’s Democratic Deficit” paper.

“In addition, rather than the current ‘opt-out’ model” for Beck-objector private employees, “which places the burden on employees to proactively exercise their rights,” Kishi continues, elected policymakers in “Congress should establish an ‘opt-in’ standard, requiring unions to secure affirmative consent from each employee before allocating any portion of dues for political activities and advocacy unrelated to workplace representation.” This has long been a conservative policy recommendation in the contexts of all employees, public or private or union member or agency-fee payer, dating back to far before both Beck and Janus.

In the private-employee context particularly, “Congress can effectuate this policy by amending Section (8)(b) of the NLRA and explicitly stating that collecting dues or fees from employees for political, ideological, or other non-representational activities without obtaining affirmative consent from each employee constitutes an unfair labor practice,” writes Kishi, a former senior policy advisor to U.S. Sen. Josh Hawley of Missouri and associate editor of The American Conservative magazine. He also recommends that “Congress should explicitly classify expenses related to organizing as ‘chargeable’ in recognition that organizing new workers directly strengthens bargaining power, benefiting all employees in the represented bargaining unit.”

Kishi further recommends amending the NLRA’s § (8)(b) to include the judicially formulated “duty of fair representation” on the part of private-sector unions—“thereby granting explicit statutory authority and providing greater legal clarity, which would reduce ambiguity and potentially enhance enforceability.” As part of his suggestion, “Unions would be legally required to meaningfully consult with their members through polling or other direct engagement before endorsing candidates or engaging in political advocacy. With this statutory clarity established,” the NLRA-created National Labor Relations Board “could issue formal rules or guidance to establish clear, enforceable standards for consultation.” That would require further delineation, of course, likely after more litigation.[1]

In a follow-up article about the idea in American Compass’ online Commonplace magazine, Kishi concludes, “Applying the duty of fair representation to political activity would help restore” trust in unions among their own members. “If unions want to speak for all workers, they must first talk to them.”

Like

The pool of funds from which the incentivization of (c)(3) groups are drawn is likewise mandatorily collected, in the form of taxes. If you owe them, don’t try not paying them.

Like labor unions, charitable nonprofits also enjoy the benefit of tax-exempt status, in the latter case under IRC § 501(c)(3). Specifically, the legislation authorizes use of the massive pool of government funds created by taxation to incentivize the creation and operation of, by its own terms,

Corporations, and any community chest, fund, or foundation, organized and operated exclusively for religious, charitable, scientific, testing for public safety, literary, or educational purposes, or to foster national or international amateur sports competition …, or for the prevention of cruelty to children or animals, no part of the net earnings of which inures to the benefit of any private shareholder or individual, no substantial part of the activities of which is carrying on propaganda, or otherwise attempting, to influence legislation (except as otherwise provided in subsection (h)), and which does not participate in, or intervene in (including the publishing or distributing of statements), any political campaign on behalf of (or in opposition to) any candidate for public office.

According to another IRC provision, contributions to these same (c)(3)s are also tax-deductible, an additional benefit. All in pursuit of the wider public interest, those who voted to create the benefits thought.

Big Labor has long had a lot of power to mandatorily extract dues and fees from those workers who may individually not have seen any worth in paying them—including, as shown above, because of its political stances and activities funded by their money. In large part because of those activities and what is easily considered the unfairness of compelled subsidization of a viewpoint contrary to that of a particular worker, unions’ power to wrest those funds has been diminished in certain specific contexts.

The pool of funds from which the incentivization of (c)(3) groups are drawn is likewise mandatorily collected, in the form of taxes. If you owe them, don’t try not paying them. In equally large part because of (c)(3)s’ political activities—and what would also easily be considered the unfairness of compelled taxpayer subsidization of their political positions—the ability of both nonprofit, money-raising public charities and nonprofit, grantmaking private foundations to spend funds on politics has been diminished in certain contexts.

In 1954, what’s called the “Johnson Amendment”—since proposed by then-Sen. Lyndon Johnson of Texas—conditioned all (c)(3)s’ privileged tax status on their not “participating in, or intervening in (including the publishing or distributing of statements), any political campaign on behalf of any candidate for public office.” The 1969 Tax Reform Act (TRA) added more conditions on the special status of (c)(3) private foundations, in the wake of what enough in Congress considered their abusive politicization of the section’s purposes and thus that status.

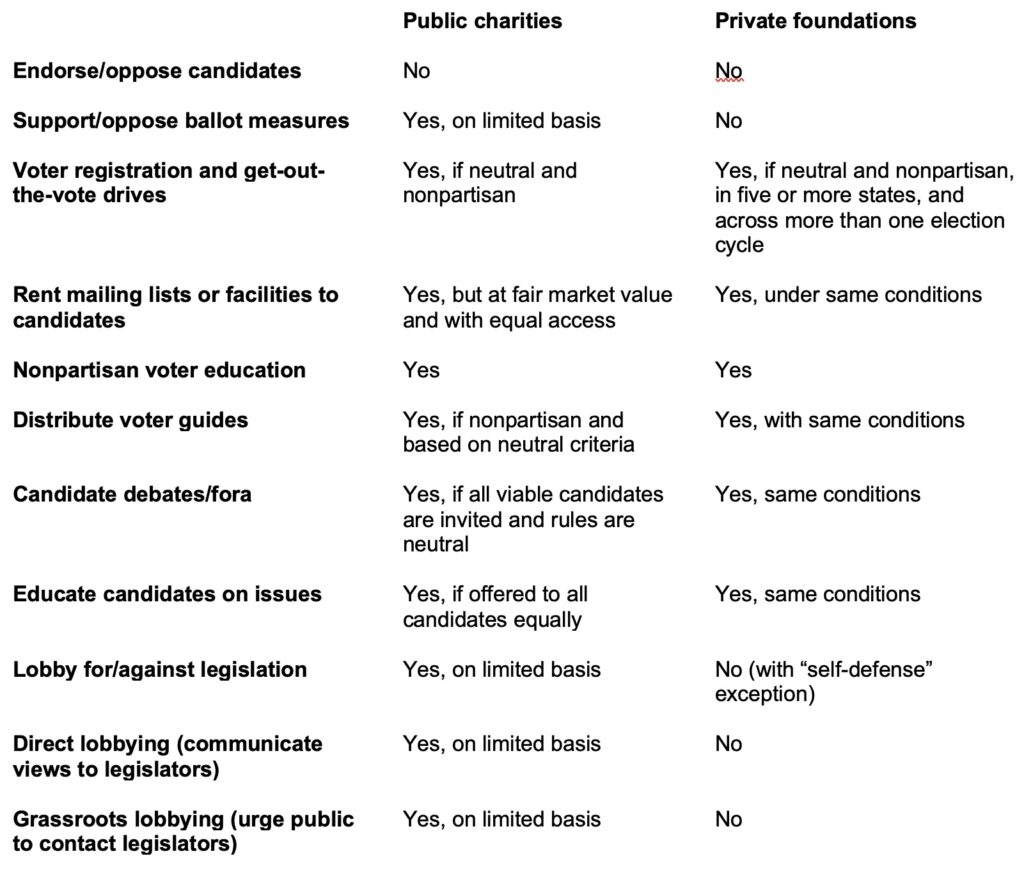

In its The Rules of the Game: A Gude for Election-Related Activities for 501(c)(3) Organizations in 2018, the progressive Alliance for Justice (AFJ) tracks what (c)(3) public charities and private foundations can engage in or fund when it comes to political and lobbying activities, if they want to avoid having them be considered “taxable expenditures” by the Internal Revenue Service and ultimately jeopardizing their exempt status. Election law may sometimes also be applicable.

Relying in large part on AFJ’s thorough work, an overview:

Lot of necessary delineation there, too.[2]

As unions are able to affiliate themselves with a political-action committee (individual contributions to which are voluntary) that can raise and spend money on politics, nonprofit (c)(3) public charities are able to affiliate themselves with the status of a social-welfare group under IRC § 501(c)(4) (contributions to which are not tax-deductible) that can raise and spend money on political activities, as long as those activities do not become what IRS guidance calls the group’s “primary activity.”

Unlike

Does there come a point at which the nature and level of these kinds of government support of nonprofits—and the understandable, though perhaps unfortunate, motive on the part of nonprofits to maintain and increase them—make the nonprofit sector, or large parts of it, just as “inherently political” as Janus’ considered public-sector unions to be?

Neither NLRA-assisted Big Labor nor tax-incentivized Big Philanthropy is depoliticized. In fact, they’re arguably both more politicized than ever. Efforts to extract them from politics have not fully succeeded—though perhaps just not yet, of course. There have been some small, incremental policy advances towards extrication, giving rise to the lots of necessary legislative and regulatory delineations between permissible and impermissible activities of private-sector unions after Beck and nonprofit public charities and private foundations in the wake of the 1969 TRA.

In the union context, there has also been the appreciably large-increment, judicial advance of Janus’ empowerment of public-sector union members to object to and flee from any compelled subsidization—to avoid being “shanghaied for an unwanted voyage,” as Alito noted in the opinion. In the charitable-nonprofit context, the smaller-increment, ’69 TRA advances may have served only to temporarily stave off politicization for a time. Larger increments are necessary.

As Janus considered the distinction between those unions representing public-sector versus those representing private-sectors members determinatively relevant because of public-sector union bargaining being inherently political, the fraught relationship between the nonprofit sector, including philanthropy, and democracy may similarly be relevant to any evaluation of its politicization and what to do about it, including in policy.

Private foundations have always had a tenuous place in America’s social contract. As for the place of those public charities they support, it has been made much more delicate by their politicization, as well, along with their arguably more-direct government support in the form of grants and contracts. Does there come a point at which the nature and level of these kinds of government support of nonprofits—and the understandable, though perhaps unfortunate, motive on the part of nonprofits to maintain and increase them—make the nonprofit sector, or large parts of it, just as “inherently political” as Janus’ considered public-sector unions to be? Aren’t we close, or closer than ever before, to that point? If so, what could and should be done?

There is no and couldn’t ever be any equivalent exercise of what would be “Janus rights” in the nonprofit context. Nor is or could there ever be any parallel exercise of Beck rights, for that matter; there are no “members” or “nonmembers” as there are in unions, but citizens who must pay taxes if and when they make enough income. Further expansions of tax-deductibility for donations to nonprofits might encourage more taxpayers to engage in charity, yes, and that might be good. Such would not really be a mechanism through which they can express discontent with bigger philanthropy as it’s currently being conducted, though.

Politics and purposes, disputes and discipline, the Bigs and bigger benefits

Anti-elite populists, conservative and progressive ones alike, should also support any advances toward checking the power of politicized, progressive Big Philanthropy. . .

Again, democratic politics is one of the few remaining ways for those citizens to object to nonprofitdom’s activities, including its politicized and partisan ones, to be expressed and take shape in elected policymakers’ reform. Politics in and of itself is a good thing, the method on which our social contract relies to manage if not resolve dispute. It would be dissonant to argue against the politicization of politics. Politicization does not violate politics’ purpose; it’s the politicization of other-purposed institutions that strain them beyond recognition, beyond those other purposes. In America, politics as we understand it is generally subject to the discipline of popular elections—unlike almost all of the other politicized institutions, which are trying to avoid that kind of or any “imposed” discipline.

Kishi’s proposed statutory expansion of Beck rights to allow private-sector union members to internally exercise them is a positive advance toward some additional, purpose-driven discipline on the activities of progressive Big Labor—as would be the policy he suggests to hold unions to account when they blatantly ignore the wishes of those whom they’ve been given a statutorily assisted role to collectively represent. All conservatives should support anti-politicization measures like these, even though they might benefit unions. They would benefit union members and the wider working class, too.

Anti-elite populists, conservative and progressive ones alike, should also support any advances toward checking the power of politicized, progressive Big Philanthropy—which may, it seems, have to come in larger increments than heretofore. Janus-sized incremental policy advances, in this context, will be difficult to achieve. They would likely need be part of a longer-term, disciplined, patiently executed political and policy-reform effort, involving nontraditional allies in a coalition. They’d benefit the nonprofit sector, even-wider civil society, the true charity practiced in both, and thus America’s common good.

—

[1] There are other potential legislative expansions of employee rights that would fall far beyond being a challenging route on which to pursue reform, but they’re worthy of note. Somewhere in between interesting “thought experiment” and outright fanciful, they would include banning public-sector unions and passing a national right-to-work law.

[2] Earlier this year, in a motion seeking judicial approval for a proposed settlement with plaintiffs in a federal case filed by two churches and a religious-broadcasters’ group alleging that the Johnson Amendment violated their First Amendment rights, the IRS agreed that if a house of worship endorsed a candidate to its congregants, it would view that not as campaigning, but as a private matter, like “a family discussion concerning candidates.”

“Thus, communications from a house of worship to its congregation in connection with religious services through its usual channels of communication on matters of faith do not run afoul of the Johnson Amendment as properly interpreted,” according to the document, filed jointly with the plaintiffs.

As of this writing, the court has yet to rule on the motion—which ruling would also require further delineation, of course, likely after more litigation.