Most people who reach a certain stage in their careers rightly consider themselves professionals. But being a professional doesn’t mean taking on $200,000 of debt for graduate school is a good idea. Unfortunately, this fairly obvious lesson is lost on some members of Congress.

Last year’s One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBB) imposed limits on graduate student loans from the federal government for the first time since 2006. Graduate degrees may be one of two categories—standard degrees, for which the aggregate federal loan limit is $100,000, and “professional” degrees, which have a loan limit of $200,000. The logic is to ensure that student debt stays reasonable for most graduate students, while maintaining higher loan limits for certain high-cost degrees that lead to high-wage careers.

The Education Department, entrusted with drawing the exact line between standard and “professional” degrees, landed on a narrow definition of the latter that includes medicine, dentistry, law, clinical psychology, and a handful of other fields. Cue the outrage from every graduate school left out of the definition. Now universities that want to keep the graduate-loan gravy train rolling are pressing Congress to expand the definition of “professional”—and things have spiraled out of control.

The Professional Student Degree Act, introduced by Representative Mike Lawler (R-NY) and a handful of other moderate Republicans, would amend the definition of “professional degree” to include a long list of additional fields. The bill names legitimate edge cases such as advanced nursing degrees, but also includes social work, business administration, accounting, architecture, education, ministry, and any other graduate degree the Secretary of Education deems appropriate.

By my estimate, the bill’s expanded definition would cover around 72 percent of graduate student borrowers—essentially erasing the meaning of the “professional” category.

Under OBBB, “professional” students can borrow up to $200,000 over their graduate careers. But most of the professions on the bill’s expanded list don’t pay nearly enough to justify that level of indebtedness. While $200,000 could make sense for a doctor or dentist, it would be crippling for a social worker.

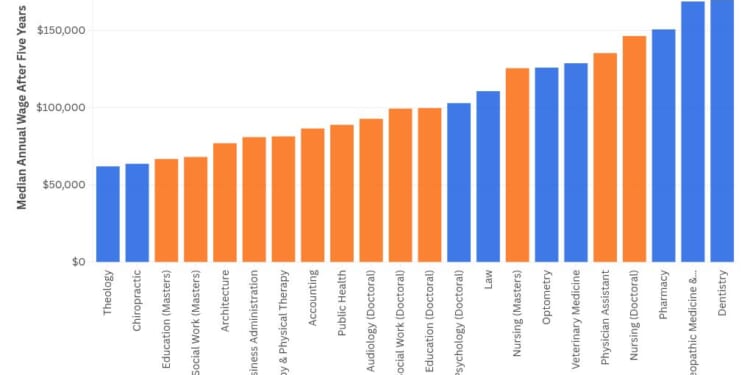

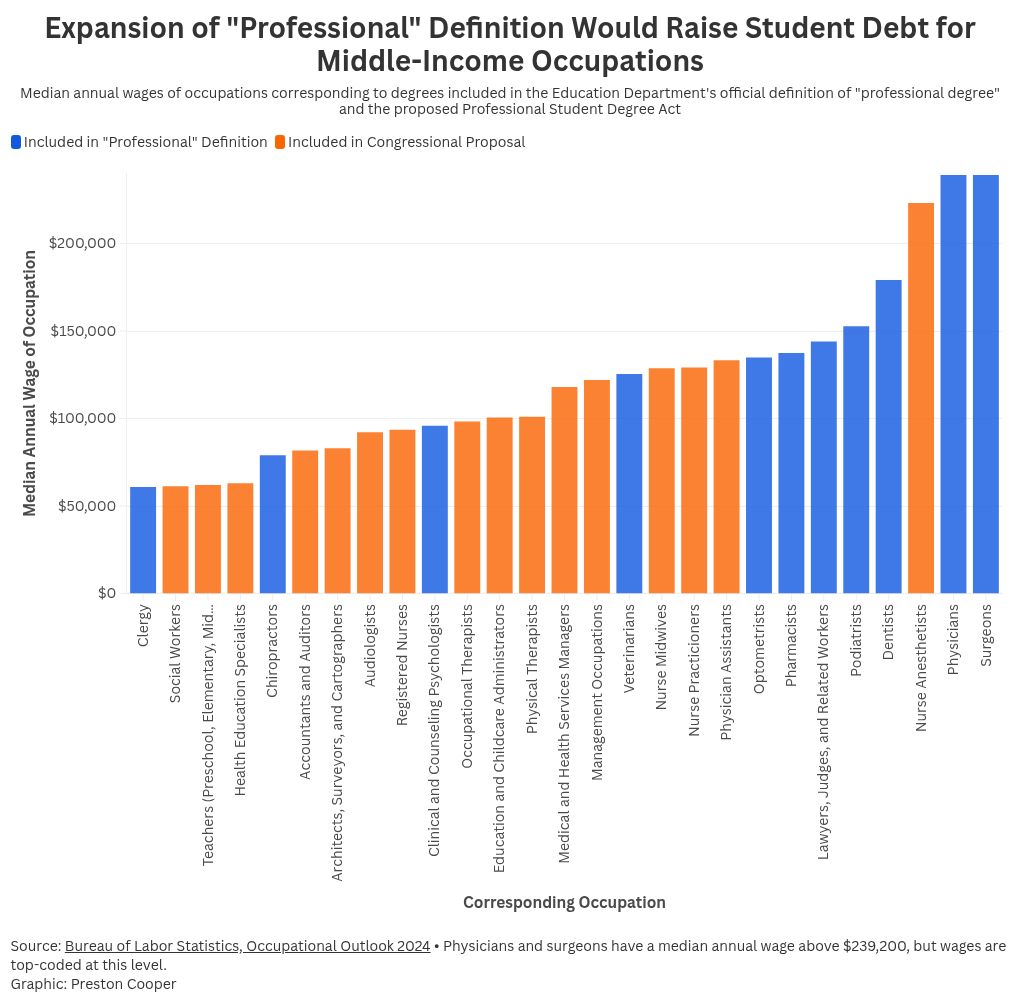

The following chart displays students’ median earnings five years into the workforce for programs included under the current definition of professional degree (in blue) and those included under the proposed expansion (in orange). Those in “professional” occupations earn a typical salary of $134,000, while those on the expanded list earn just $75,000.

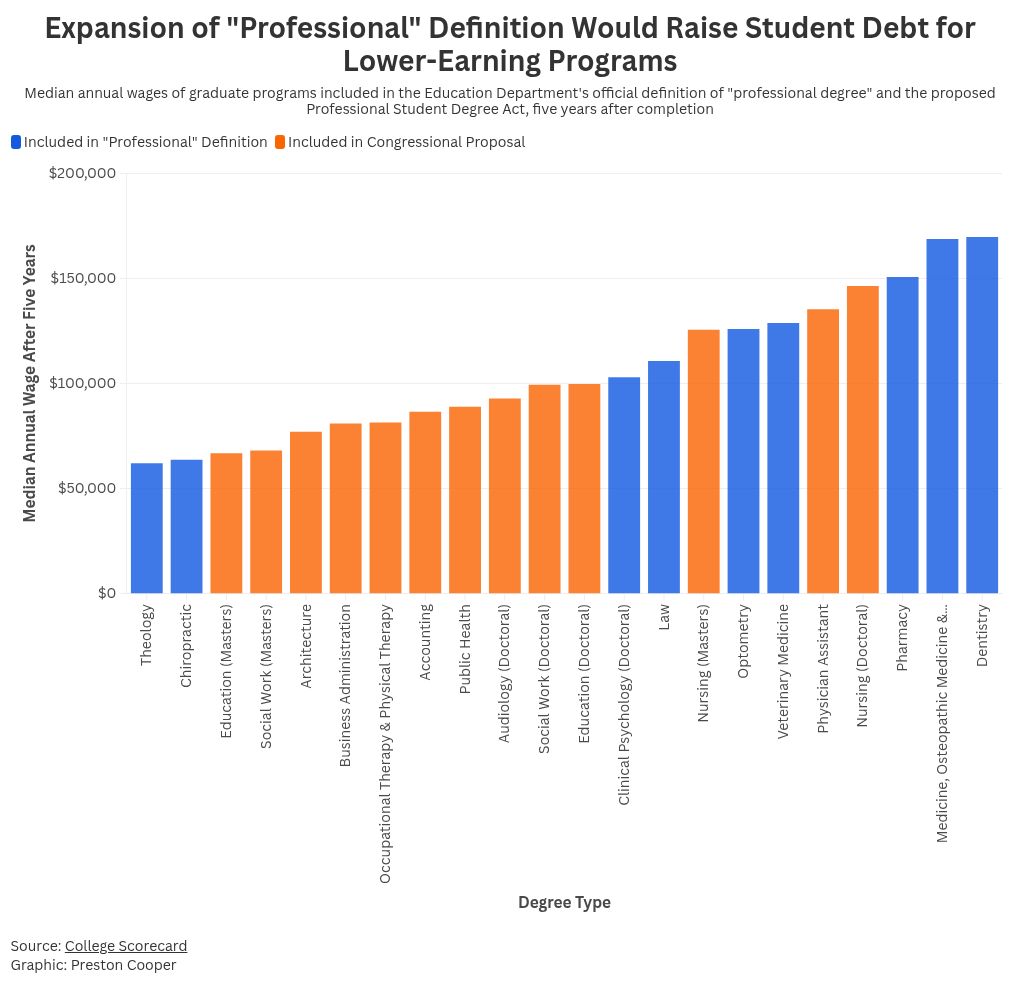

The above chart measures earnings for relatively recent graduates, whose earnings tend to be lower—but we can also analyze the median annual wages of occupations that professional degrees train for, using Bureau of Labor Statistics data. The case for a narrow definition of “professional degree” is arguably even stronger. Most occupations corresponding to current “professional degrees” pay well over $100,000. But the proposed expansion would bring extreme student debt burdens to middle-income occupations.

Congress had good reasons for imposing graduate student loan limits in OBBB. Unconstrained borrowing allowed universities to hike tuition and use graduate degrees of questionable value as cash cows. Graduate students with debt burdens out of proportion to their earnings often cannot repay their loans in full. For this reason, the Congressional Budget Office expects that OBBB’s loan limits will save taxpayers close to $7 billion per year—not to mention easing the burden of debt for hundreds of thousands of students. Much of this could be undone if Congress relaxes the limits so radically.

There are reasonable arguments for amending the current definition of “professional degree”—but in the opposite direction. Based on earnings data, theology programs should almost certainly not get access to higher loan limits; there’s a good case for dropping chiropractic and clinical psychology degrees as well. Broadening the definition to include advanced nursing and physician assistant programs might not be the end of the world, but it’s not really necessary, and Congress should be more focused on reducing student debt than expanding it.

Classifying nearly three-quarters of graduate degrees as “professional,” as the Lawler bill does, would almost fully undo Congress’ hard work of bringing sanity to the Wild West of graduate student loans. I propose a different change: call “professional” degrees “high-debt” degrees instead. The latter is a more accurate descriptor—and it might make professions think twice about lobbying for inclusion.

The post Expanding “Professional Degrees” Would Just Expand Unmanageable Student Debt appeared first on American Enterprise Institute – AEI.