Life, Liberty, Property #113: Fed’s Consensus Slips as Interest Rates Stifle Economy

Forward this issue to your friends and urge them to subscribe.

Read all Life, Liberty, Property articles here, and full issues here and here.

IN THIS ISSUE:

- Fed’s Consensus Slips as Interest Rates Stifle Economy

- Video of the Week: The Age of Trump – In The Tank Podcast #506

- Critiquing the ‘New Conservatives’

- Tariffs Don’t Cause Inflation, Wall Street Journal Says

- Cartoon

- Bonus Video of the Week: Expanding the Definition of Death – In The Tank Podcast #505

Fed’s Consensus Slips as Interest Rates Stifle Economy

The Fed’s consensus on high interest rates is slipping as economic growth slows.

The Federal Reserve (Fed) has kept interest rates high this year, even though “growth of economic activity moderated in the first half of the year,” as the Federal Open Market Committee’s (FOMC) statement admitted two weeks ago. The board on July 30 announced it would aim to keep short-term borrowing costs between 4.25 percent and 4.5 percent, as has been the central bank’s policy since December of last year.

The FOMC and Fed Chair Jerome Powell have continued to express concern that President Donald Trump’s tariffs will increase price inflation (see item 3, below). Stagnant job numbers and relatively steady prices have done nothing to change their decisions, although two governors voted against the central bank’s latest stand-still decision—the first time that has happened in three decades.

One of those two dissenting Fed governors, Vice Chair of Supervision Michelle Bowman (the other being Christopher Waller), told the Kansas Bankers Association on August 9 “recent job data corroborates her concerns over labor market fragility and backs up her position that three interest rate cuts should be instituted this year,” The Epoch Times reported in summarizing Bowman’s speech.

“Taking action at last week’s meeting would have proactively hedged against the risk of a further erosion in labor market conditions and a further weakening in economic activity,” Bowman said.

Bowman expressed concerns the economy is heading into a downturn, the paper reports:

Bowman’s remarks delved into her worries about a labor market downturn in more depth than what she expressed in a post-meeting explanation for her dissenting vote on interest rate cuts.

On Aug. 1, the Labor Department’s monthly employment report showed unemployment rising to 4.2 percent, with it “close to rounding up to 4.3 percent,” as Bowman described it in her Aug. 9 speech. There were also revisions to previously published data in the report, with job gains slowing significantly over the past three months, coming to a monthly average of 35,000.

“This is well below the moderate pace seen earlier in the year, likely due to a significant softening in labor demand,” Bowman said. “My Summary of Economic Projections includes three cuts for this year, which has been consistent with my forecast since last December, and the latest labor market data reinforce my view.”

Although it is difficult to put much trust in the job-market reports, given the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ poor track record in recent years, Bowman said she sees “the latest news on economic growth, the labor market, and inflation as consistent with greater risks to the employment side of our dual mandate.”

In addition, Bowman argues that inflation is not as likely as the rest of the committee seems to think, the paper reports:

Recent inflation data has also added to her position that Trump’s tariffs will not lead to long-term inflation, she said.

After omitting increases in goods prices related to tariffs, underlying inflation is “much closer” to the Fed’s 2 percent goal versus the official 2.8 percent measurement in June, based on the year-long change in the core personal consumption expenditures price index.

Bowman said she believes that the Trump administration’s tax cuts and deregulation will also offset any economic effects or price impacts from the tariffs.

As housing demand is at its lowest since the financial crisis, and the labor market is not pushing up inflation, “upside risks to price stability have diminished,” Bowman said.

Doing nothing is a choice, and a bad one when economic conditions change and require recalibration of policy, observes economist Bryan Cutsinger, Ph.D., at The Daily Economy:

The neutral interest rate depends in part on investment demand, which itself is closely tied to productivity growth. When firms expect productivity to rise, they’re more willing to invest in new capital projects, raising the demand for loanable funds and, with it, the neutral rate. But when productivity prospects dim—as they often do in the face of trade uncertainty: higher input costs, reduced access to more efficient foreign suppliers, and resource misallocation driven by protectionist policies—investment demand falls, dragging the neutral rate down with it.

In order for monetary policy to remain on track, the Fed must adjust its policy rate when the neutral rate changes. For example, if tariffs are pulling the neutral rate lower, then the appropriate course of action is for the Fed to cut its policy rate. By contrast, if the Fed holds the policy rate constant, as it has since December, and the neutral rate is indeed falling, then the Fed is passively tightening monetary policy. In short, the Fed’s wait-and-see approach is anything but.

The current Fed’s response to tariffs is wrong in another important way, Cutsinger argues:

At a more fundamental level, the Fed should not be responding to tariffs, even if they push prices higher. The reason is straightforward: while the Fed can influence the demand side of the economy, it has little control over the supply side—where tariffs primarily operate. Responding to supply-driven price fluctuations risks compounding the problem rather than solving it, especially if tighter policy suppresses demand in an already constrained economy.

The Fed is engaging in “passive tightening,” Cutsinger warns. “In short, when the neutral rate falls, doing nothing is not a neutral act—it’s a contractionary one,” Cutsinger writes.

Bowman is suggesting that the Fed should diverge from its usual policy of changing interest rates too much and too quickly and holding them there for too long. The FOMC is stubbornly adhering to its usual position that inflation is worse than unemployment, perhaps because inflation affects everybody and unemployment primarily affects the households of those who lose their jobs or whose wages are held down by decreased competition for workers.

Bowman is warning against that and arguing for earlier and less-extreme action by the central bank, saying that the FOMC must act to “reduce the chance that the Committee will need to implement a larger policy correction should the labor market deteriorate further.” A panicked reaction to poor job creation caused by Fed-induced monetary contraction is exactly where the FOMC is headed, and Bowman is right to call out her fellow committee members for continuing the central bank’s destructive habit of excessive delay and overcorrection.

Sources: The Epoch Times; The Daily Economy

Video of the Week

| We are only six months into the Trump Administration 2.0, and The Age of Trump is already in full swing. National Review hails his presidency as “truly historic,” outlining a laundry list of accomplishments he has already achieved. The left and right clash over what Trump’s federal takeover of Washington, D.C., really means. Is this a bold reset of a broken city or a dangerous power grab? |

Critiquing the ‘New Conservatives’

With a large segment of the American right moving away from its traditional support for free markets, “It is essential to consider the arguments of policy scholars who are advocating for a shift to a conservatism that advocates for government intervention,” writes Civitas Outlook editor in chief Richard M. Reinsch III at Law & Liberty.

Reviewing The New Conservatives, a newly published book edited by Oren Cass, chief economist of American Compass and erstwhile domestic policy director for Mitt Romney’s 2012 presidential campaign, Reinsch notes the volume’s essays push for “greater government involvement in almost every policy area” and “argue we shouldn’t focus on the consumer but on the worker, especially workers engaged in the manufacturing sector.”

These self-described New Conservatives are simply pushing warmed-over pre-1960s progressivism with some pro-family spin, Reinsch argues.

“The book is decidedly protectionist, pro-industrial policy, pro-labor union, pro-family policy, and proposes a more robust alliance between Silicon Valley and the government,” writes Reinsch. “The message is clear: entitlements shouldn’t be cut, nor should current tax rates on any labor or activity be reduced. In fact, Cass has indicated that he favors increasing taxes on wealthy Americans” (emphasis in original).

Reinsch systematically examines the New Conservatives’ assumptions and policy proposals, quickly demolishing the movement’s focus on the worker over the consumer through the simple course of asking why anybody works:

Why do we work? We indeed find meaning and frustration in our work, fellowship, and rivalries, as well as opportunities and disappointments. But through all of that, we work to consume because we need to consume; that is, we must satisfy our needs and wants, and through work, we acquire the means to engage in exchanges with others. Economically speaking, that is the point of work. Would you continue to do your job if your wages were cut by 10 percent, 15 percent, or entirely? No. You’d look for other work.

The purpose of an economy is to meet the needs of consumers, since consumption is the ultimate reason why we work.

The New Conservatives’ false premise leads naturally to bad policy, whereas the consumer-oriented approach accords with human nature:

Conclusions follow this truth. One is that consumers don’t have the responsibility to keep certain workers employed. The producer must serve the consumer. Should we be required to buy things that are redundant or that we don’t need or want, to keep existing businesses alive? That is the absurd logic of Cass’s inversion of the consumption-production relationship. Moreover, feeding, housing, and clothing one’s family are essential expenses. How is making these consumption expenses more expensive pro-family?

After extensive criticism of Heritage Foundation President Kevin Roberts’ arguments in favor of greater government action, encapsulated by Roberts’ contemptuous dismissal of “the abstract economic pronouncements of some long-dead Austrian aristocrat”—meaning Friedrich von Hayek, “one of the foremost economic, institutional, and legal thinkers of the twentieth century,” in Reinsch’s accurate description—Reinsch turns to the specifics of the New Conservative complaints and checks them against the facts:

Did the working class meet its demise at the hands of free trade, NAFTA, and the WTO as Cass and Roberts insist? No. As AEI economist Michael Strain and investor Clifford Asness observe: “The wages of nonsupervisory workers—roughly the bottom 80 percent of workers by pay, including manufacturing workers and service-sector workers who are not managers—have grown by around 60 percent over the past two generations. Over the past three decades, inflation-adjusted wages for typical workers have grown by 44 percent.”

Strain and Asness cite a different finding on overall wealth accumulation, observing that data from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) notes that “families in the 51st to 90th percentiles of the wealth distribution had an average wealth of $1.3 million in 2022, the most recent year data are available. That’s up from around $500,000 in 1990, after adjusting for inflation.”

What about those with low incomes, Strain and Asness inquire? “The CBO’s income data show that inflation-adjusted post-tax-and-transfer income for the bottom 20 percent of households more than doubled from 1990 to 2021.” And “these families saw their average real wealth triple from 1990 to 2022.” Poverty rates have declined using the government’s official measure from above 20 percent in 1960 to 11 percent today. The standard is relative, so some poverty will always be found.

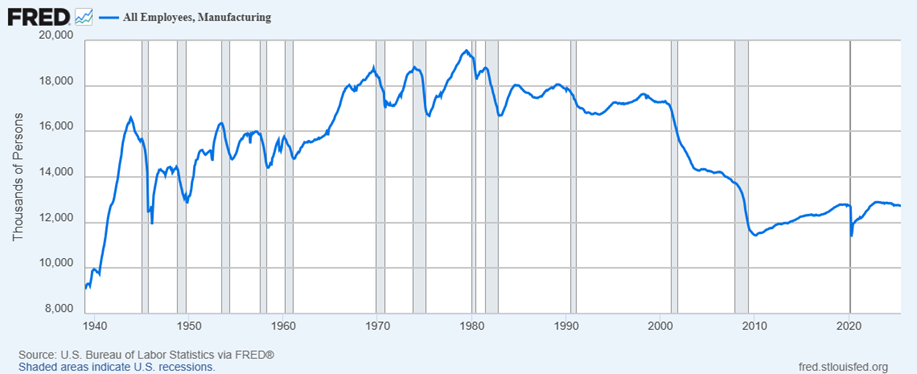

What about the boys down at the plant? Are we overlooking them?

In their famous paper describing the “China Shock,” David Autor, David Dorn, and Gordon Hanson observed a 13-year period from 1999 to 2011, concluding that imports from China resulted in a 21 percent decline in manufacturing employment, or a net loss of 2.4 million jobs. Numerous scholars have since questioned these findings of such job losses, reducing the number by half or even more. We should note the number of jobs created in America by imports, which economists also point to in evaluating China Shock.

Sympathy for those struggling through economic and social changes should not blind us to reality, and it is especially important not to ignore positive changes, Reinsch observes:

I don’t diminish job losses or the psychological toll they exert. It is a natural part of any freely functioning economy, however, and an inherent aspect of capitalism and America’s economic history. Six million jobs were also created during this same period in other sectors of the economy. Economist Jeremy Horpedahl has recently tested the jobs and incomes of the 10 cities most negatively affected by the China Shock. His findings indicate that most of them currently boast more jobs than they did in 2001. Moreover, these same cities have higher real wages for workers at every income level. Amidst the current push for reindustrializing America, we might wonder who will fill the already 450,000 open manufacturing jobs? Declinist narrative and DC opportunity mill meet economic reality.

Recognizing that new opportunities have arisen in place of old ways of doing things does not amount to callously telling people to “learn to code,” as the cliché has it. The U.S. economy has become more productive over the years, which is the only way to increase prosperity. The loss of jobs in the manufacturing sector is a result of a great increase in productivity, Reinsch writes:

In meeting the needs of consumers, the American manufacturing sector has increased productivity since 1994, the year NAFTA was implemented, by between 70-80 percent. As George Mason University economist Don Boudreaux has noted in this space, “the productivity of American manufacturing workers steadily increased from the end of WWII until 2012; it neither stopped nor even slowed when America’s run of annual trade deficits started in 1976.” This productivity increase came at a time when this same sector began to shed jobs in earnest towards the end of the 1970s. This would be evidence of a robust sector, and yet virtually every Western country has watched its manufacturing sector decline during this period. America differs in that its manufacturing sector’s productivity is almost unmatched. Besides, as Harvard Kennedy School, NBER, and Peterson Institute economist Robert Lawrence has noted, productivity growth is the “dominant force behind the declining share of employment in manufacturing in the United States and other industrial economies.”

We can quibble with why manufacturing productivity has not continued to increase since 2012, but we might consider consumers again, who, as they grow richer and live in more prosperous economies, choose to devote fewer resources to manufacturing goods. America is now a service-based economy, and if we are going to speak the language of trade deficit and surplus, it’s one in which we have a definite surplus. One can feel the collective shudder from the economic nationalists, but these are facts that can only be changed with economically suboptimal government interventions.

Greater productivity means fewer people are needed to produce a given amount of goods. That is undeniably a positive development. Productivity improvements are why the number of manufacturing jobs has fallen from its late-1970s peak:

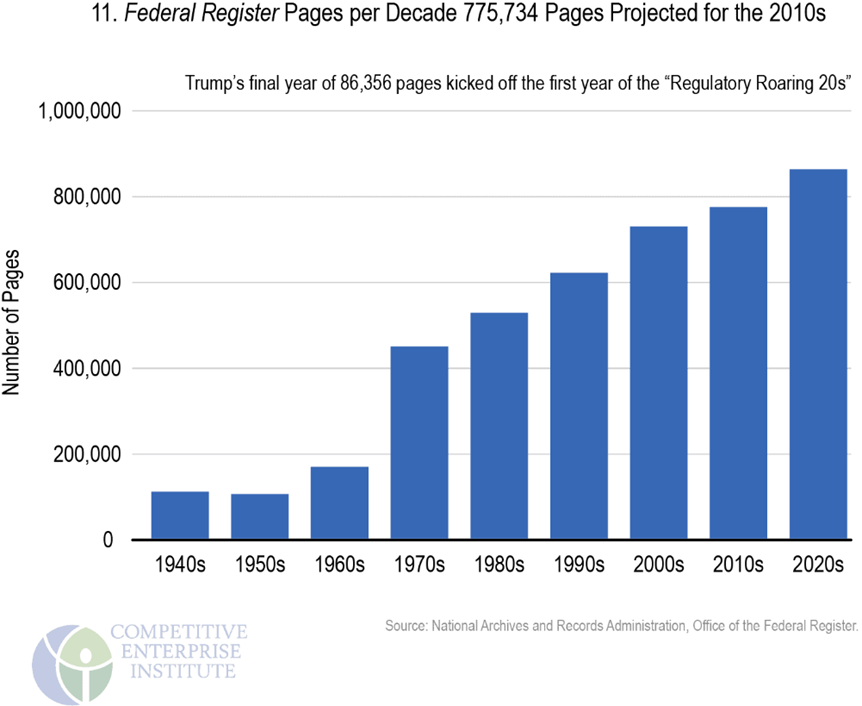

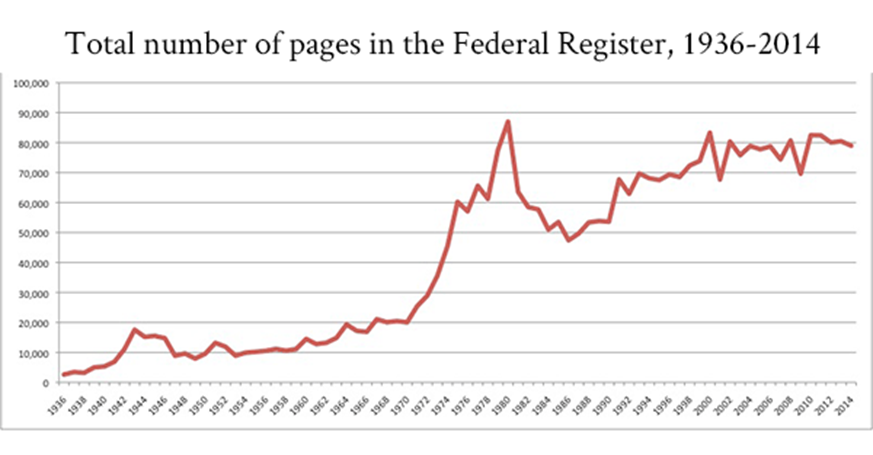

Those job losses did indeed hollow out the economies of the Rust Belt states, but that did not have to happen. Although Reinsch does not go into this in his essay, it is important to note here that government regulation ballooned in the 1970s, as did energy prices in the wake of President Nixon’s severing of the final tenuous connection between the dollar and gold, accompanied by a massive increase in environmental regulations, deterioration of the nation’s education system, and gigantic increases in the welfare state. In addition, the nation imported tens of millions of workers, both legally and otherwise.

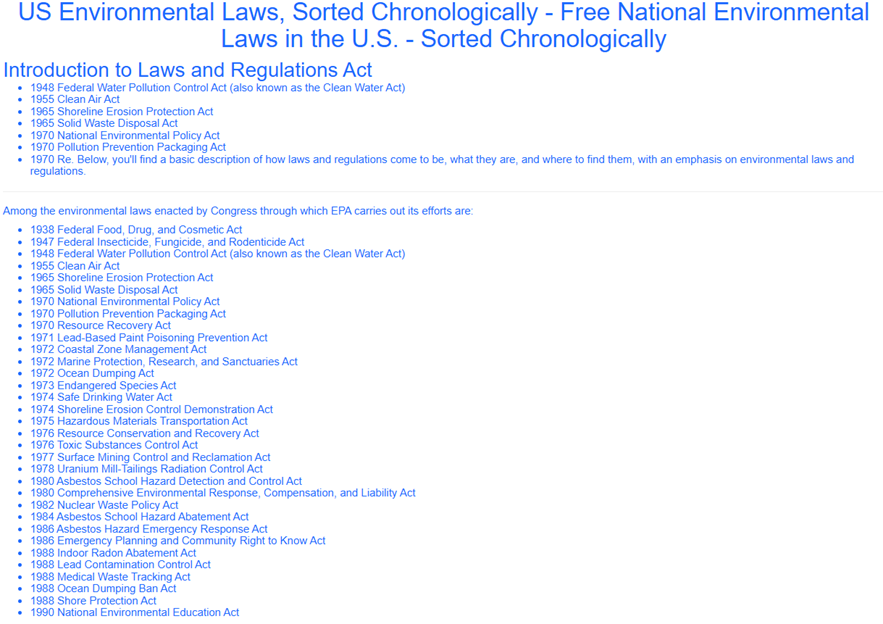

Source: Ten Thousand Commandments, by Clyde Wayne Crews, 2021

Source: EHSO.com

Those and other government actions increased employers’ costs and reduced American-born workers’ market value. The damage was worst in the places where manufacturing had been strongest, what became the Rust Belt.

If anyone betrayed American workers regularly since the 1960s, it was the U.S. government, and not through free trade but by excessive regulation (especially through environmentalism), currency devaluation, encouragement of expansive immigration, welfare state expansion, and countless other destructive policies. The interventionist style of government that the New Conservatives advocate is what brought on the very destruction of which they now complain.

The New Conservatives want to increase marriage and family formation, reduce immigration, and increase employment in traditional industries. Among those goals, only immigration requires positive government action, and that means managing the border, which President Trump has confirmed to be a surprisingly simple task.

Issues such as employment and family formation are best left to the people themselves, and the key to that is to reduce government involvement to the absolute minimum. Activist government is the problem, not the solution.

It is positively baffling that we have to remind self-styled conservatives about this after so many years of catastrophic government intrusion into every facet of American life. Have they already forgotten the pandemic years and Biden administration? (Eight months ago!)

Governments badgering people to get experimental injections, forcing small businesses to close, forbidding Americans from going to church, arresting people for going to the park, censoring communications, engaging in politicized prosecutions, and lying about absolutely everything—that is what big government did in just the past few years.

The New Conservatives want to go farther in subjecting the family and the American worker to the very entity that has done the most to undermine them by far. That is not conservatism, nor is it sensible. The job of the federal government is to protect our country from invasion, resolve disputes among the states and ensure that they have republican governments, manage relations with other nations, ensure the existence of reliable currency, prevent interstate fraud and criminal violence, and the like. With those things taken care of, Americans are perfectly suited to build things and create families on their own.

The New Conservatives are selling an un-American mindset, a culture of grievance and self-pity that rejects the nation’s fundamental values of independence, hard work, and self-reliance. Reinsch writes,

With data like this, Americans should wonder why they are consistently being misled by leaders on the populist left and right. Such doomsaying about the demise of the working class and the decline of the industrial heartland serves as a dangerous introduction to a politics of grievance, providing a powerful platform to those pushing these views. Our problems in education, family, patriotism, and work rates are undeniable, and many of them Roberts identifies correctly, but rooting them primarily in an economy built on the betrayal and deceit of hard-working Americans is simply false.

The New Conservatives are effective at publicizing the current problems plaguing the United States. They are wrong about the causes and dangerously wrong about the solutions, demanding the very same thing that caused the problems in the first place: government power. Fortunately, their prescription has little public support, Reinsch writes:

… the economic populist program that Roberts and Cass endorse is not endorsed by most GOP voters, who continue to want traditional objectives of economic growth, limited and competent government, low crime, lower prices, and economic opportunity, plus an end to the ideological revolutionary nostrums of the Left.

The New Conservatives’ concern for the American worker and American families is laudable. Their diagnoses of the ills that have befallen vast swaths of the American people over the past century are all wrong, as are their proposed remedies.

“Today’s conservatives in Washington stand on the shoulders of ideas, research, and statesmanship that took decades to build. They would do well to improve it, not denigrate it,” Reinsch writes.

The American right has always manifested sympathy for ordinary, hardworking people and advocated policies that free Americans to build, create, and enjoy the fruits of their investments of time, labor, and money. The New Conservatives want to rebuild the nation’s families, economy, and culture. The free-market right knows the way to do this. The American Way.

NEW Heartland Policy Study

‘The CSDDD is the greatest threat to America’s sovereignty since the fall of the Soviet Union.’

Tariffs Don’t Cause Inflation, Wall Street Journal Says

Tariffs do not cause inflation, The Wall Street Journal’s editorial board stated last week:

Inflation is a broad-based, persistent increase in the general price level. Tariffs in that sense aren’t inflationary unless the Fed accommodates them with over-easy monetary policy. But tariffs do raise prices on tariffed goods, which can mean a one-time surge with some potential downstream effects. What matters for voters, and for their confidence in the economy, is what they see in their own paychecks and cost of living.

Sentences one and two in that quote are exactly what I have been mentioning throughout the ongoing discussion of Trump’s tariffs over the past several months. Sentence three is rather confused in suggesting that the “surge” in prices is an overall effect that is not compensated for by decreases in prices of other goods and services to compensate for those price rises. Sentence four is essentially fact-free rhetoric.

The subsequent paragraph—the conclusion of the editorial—basically ignores the initial admission about inflation:

Republicans are in the political danger zone if tariffs cause price increases—one-off or persistent—that aren’t offset by bigger wage gains. Republicans will make the same mistake as the Biden Administration if they keep telling voters everything is fabulous but the evidence at the grocery store or Applebee’s tells them something different.

The Journal’s admission is particularly significant because the paper has been highly critical of President Donald Trump’s tariff plans and continually said that they will cause inflation. Inflation is the province of the Federal Reserve and federal fiscal policy (viz. deficit spending), not of trade policy, and being accurate about actions and their consequences is a rather important thing, I think.

It is perfectly reasonable to oppose Trump’s tariffs because they are taxes and in light of the fact that taxes distort economic activity. Those things are both true, unlike the inflation claim, and they are potentially sufficient to establish that the Trump tariff regime does more harm than the good the president and his team say it will do.

That is the issue the Journal’s editors and reporters should have been addressing all along, instead of raising specters that vanish in the morning light.

Source: The Wall Street Journal

Cartoon

via Townhall

Bonus Video of the Week

A recent and highly disturbing New York Times article promoting the idea that doctors should expand the definition of death in order to harvest more organs is stirring up disgust and debate about utilitarianism and the role of doctors or so-called “bioethicists” in shaping medical policy. What is the current state of the organ donation industry and what kind of policy actually makes sense? How far is too far when it comes to medical care?

Contact Us

The Heartland Institute

3939 North Wilke Road

Arlington Heights, IL 60004

p: 312/377-4000

f: 312/277-4122

e: [email protected]

Website: Heartland.org