from the getting-one-right-for-a-change dept

Just because a constitutional violation is easy to ignore doesn’t make it any less of a constitutional violation. And yet, that was the first defense of Louisiana’s Ten Commandments mandate offered by the governor of the state, Jeff Landry.

When asked what he would say to parents who are upset about the Ten Commandments being displayed in their child’s classroom, the governor replied: “If those posters are in school and they (parents) find them so vulgar, just tell the child not to look at it.”

That’s not an appropriate response to complaints raised about a clearly unconstitutional action by the government. It’s not a matter of “vulgarity.” It’s that no one should be forced to ignore violations of their rights just so they can attend public school.

Of course, this wasn’t the defense offered to the judge handling the inevitable lawsuit in federal court. But even the state’s better defenses were incapable of salvaging the sort of church-plus-state government action that just as inevitably ends in courtroom losses for overreaching lawmakers.

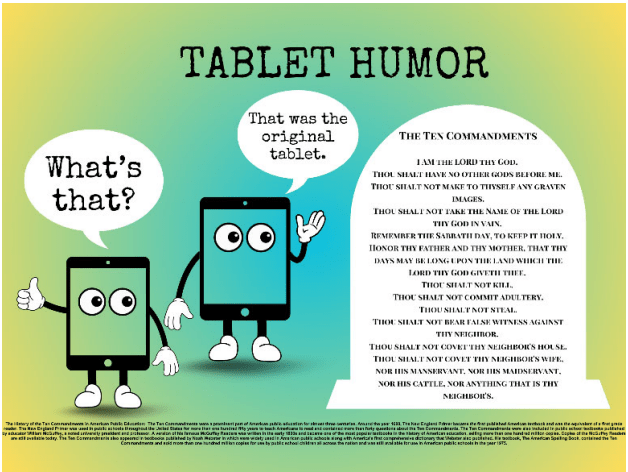

The federal court wasn’t amused by the government’s attempt to avoid judgment by getting cutesy with proposed classroom posters like this one:

Before declaring the Ten Commandments mandate “inconsistent with the history of the First Amendment and public education,” the court had this to say to Louisiana’s legal reps:

Plaintiffs do not seriously dispute that they mount a facial challenge, so, under Croft, they must prove the Act is “unconstitutional in every application” and that there is “no set of circumstances under which” the Ten Commandments could be posted in compliance with the Act that would be constitutional. Plaintiffs lament that Croft is the only Establishment Clause case in the Fifth Circuit to reach this result, but Croft remains binding precedent that this Court must follow.

AG Defendants treat this as a kill shot. They maintain that they can comply with the Establishment Clause by surrounding the Ten Commandments with nonreligious matter no matter how outlandish that material might be. That is to say, AG Defendants believe they can constantly change their iterations, leaving potential challengers like Menelaus trying to seize and hold the ever shape-shifting Proteus until Proteus eventually tires and divulges the hero’s way off the island. See HOMER, THE ODYSSEY 135.391–142.644 (Robert Fagles trans., Penguin Books, 1997). Or, phrased another way, AG Defendants would have aggrieved parents and children play an endless game of whack-a-mole, constantly having to bring new lawsuits to invalidate any conceivable poster that happens to have the Decalogue on it.

The state appealed this decision immediately. And by “immediately,” I mean pretty much before the bits on the PDF even had a chance to dry. Both the decision and the appeal hit the docket on November 12 of last year.

Nearly seven months later, we finally have a response. The Fifth Circuit Appeals Court upholds [PDF] the lower court’s decision while making some of its own very solid points about the obvious unconstitutionality of this mandate.

The state tried to argue that the plaintiffs had alleged no legal “injury” from the mandated posting of the Ten Commandments in public schools and universities. It also claimed the lower court failed to develop allegations enough to warrant its decision. The Fifth Circuit says both arguments are wrong, especially since the only supporting arguments have been cherry-picked from a handful of non-binding decisions from other courts (including the Supreme Court).

The plaintiffs have standing to sue. And the law is clearly unconstitutional. The precedent that actually matters is nearly 50 years old, something the state’s legal counsel might have pointed out before Governor Jeff Landry signed this into law.

Perhaps no better case illustrates the nature of H.B. 71’s constitutional problem than Stone v. Graham, 449 U.S. 39 (1980) (per curiam). In Stone, the Supreme Court struck down a Kentucky statute requiring that the Ten Commandments be displayed on the wall of every public classroom in the state because it had no “secular legislative purpose.”

[…]

According to Kentucky, the statute’s secular legislative purpose was reflected on the displays in a small notation below the Commandments: “The secular application of the Ten Commandments is clearly seen in its adoption as the fundamental legal code of Western Civilization and the Common Law of the United States.” The Court held that the state’s avowed purpose was a sham, and the statute was therefore unconstitutional. It explained, “[t]he pre-eminent purpose for posting the Ten Commandments on schoolroom walls is plainly religious in nature. The Ten Commandments are undeniably a sacred text in the Jewish and Christian faiths, and no legislative recitation of a supposed secular purpose can blind us to that fact.”

Nearly fifty years later, Louisiana is trying the same bullshit when faced with a legal challenge.

The statute does not require that the Ten Commandments be integrated into a curriculum of study. On the contrary, under the statute’s minimum requirements, the posters must be indiscriminately displayed in every public school classroom in Louisiana regardless of class subject-matter. See La. R.S. § 17:2124(B)(1). Louisiana insists, however, that unlike Kentucky, its Legislature has a valid “secular historical and educational purpose” for displaying the Ten Commandments in classrooms, which is reflected in the statute.

[…]

Louisiana’s purported legislative purpose states:

It is the Legislature’s intent to apply the decision set forth by the Supreme Court of the United States in Van Orden v. Perry, 545 U.S. 677 (2005), to continue the rich tradition [of including the Ten Commandments in the education of our children] and ensure that the students in our public schools may understand and appreciate the foundational documents of our state and national government.

This is similarly a “sham,” says the Fifth Circuit:

It is also unclear how H.B. 71 ensures that students in Louisiana public schools “understand and appreciate the foundational documents of [its] state and national government” when it makes displaying those “foundational” documents optional, and does not require that they also be printed in a large, easily readable font. La. R.S. § 17:2124(A)(9). When the Ten Commandments must be posted prominently and legibly, while the other “contextual” materials need not be visible at all, the disparity lays bare the pretext.

The injunction stays in place and the lower court’s ruling is upheld. And state lawmakers will have to take their crayons back to the drawing board if they hope to shove their preferred god down children’s throats. Better yet, the next time some dumbass bill like this gets proposed, they could apply the wisdom of Governor Landry and just decide to look at something else instead.

Filed Under: 1st amendment, 5th circuit, establishment clause, free speech, freedom of religion, jeff landry, louisiana, ten commandments