Executive Summary

Antidiscrimination law has become a flashpoint in American political debates once again. With the Supreme Court’s decision striking down affirmative action and a legal campaign against race-conscious “diversity, equity, and inclusion” (DEI) programs—a campaign that now enjoys the support of the executive branch—there has been increased attention to how these laws protect not only black, Hispanic, and Native Americans, but also white and Asian Americans. Some on the right have also resuscitated age-old libertarian arguments that antidiscrimination law necessarily violates freedom of association and should be pared back in general. Meanwhile, given ongoing racial gaps in many important outcomes, DEI advocates on the political left have fought to protect and expand race-conscious programs and policies.

This report explains the history and current state of play of antidiscrimination law, with a focus on racial discrimination in employment, contracting, housing, and admissions to selective schools and colleges—areas in which interpersonal discrimination can limit access to important opportunities. It also assesses the role of discrimination in racial disparities over time and offers suggestions for reform.

The main conclusions:

- America’s antidiscrimination laws were, of course, motivated by a desire to stamp out the widespread antiblack bias that pervaded the country during the civil-rights era. However, as written, they are broadly colorblind and unambiguously prohibit discrimination against all races.

- Antiblack discrimination has waned remarkably since the 1960s, but a meaningful level persists today and is a legitimate reason for concern and action. However, racial discrimination by itself—differential treatment of people because of their race, with all else held equal—does a poor job of explaining overall racial gaps. Human capital and family structure have become far more important factors, suggesting that improvements in those areas, while outside the scope of this report, would be necessary to equalize outcomes.

- Meanwhile, discrimination against “overrepresented” groups—sometimes explicit—provokes resentment, backlash, and lawsuits.

- The most promising path forward for antidiscrimination law would provide consistent and equal protection to all Americans against racial discrimination by governments and business entities. This should include a continued effort, using rigorous data analysis and audits, to identify and eliminate bias against black Americans and other minorities. It also means taking antiwhite and anti-Asian discrimination seriously.

- Antidiscrimination law should never actively discourage meritocratic, data-driven decision making. Objective and transparent processes are not discriminatory—indeed, they help to avoid discrimination based on illegitimate criteria.

Put simply, the way forward is to fight discrimination and legalize meritocracy.

Introduction: The Colorblind Backbone of Antidiscrimination Law

In 1868, following the North’s victory in the Civil War and a debate over Congress’s authority to protect civil rights in the South, the nation added the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution. It guaranteed citizenship to all “persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof.” It also forbade states to deny citizens the “equal protection of the laws,” the “privileges or immunities” of citizenship, or the “due process of law.” Congress was given the authority to enforce the amendment through “appropriate legislation.”[1]

Legal scholars have long debated the outer limits of these vaguely worded rights as originally understood.[2] In practice, however, many forms of state-sanctioned discrimination, including mandatory segregation in schools and public places, persisted until the mid-20th century. At that point, courts and Congress set much more explicit rules.

The Supreme Court, most prominently in the 1954 school-segregation case Brown v. Board of Education, adopted a more expansive reading of what the Fourteenth Amendment required of government actors. The following decade, Congress broadly prohibited discrimination not only by state actors but also by private businesses and schools, drawing on numerous authorities, such as those allowing it to regulate interstate commerce and to disperse (and set limits on) federal funds. More than 50 years later, these statutes and precedents are now well-settled, publicly accepted law.

It is helpful to understand the actual statutory text that prohibits various forms of discrimination under federal law:

Employment: Under Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, it is illegal for an employer with at least 15[3] employees “to fail or refuse to hire or to discharge any individual, or otherwise to discriminate against any individual with respect to his compensation, terms, conditions, or privileges of employment, because of such individual’s race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.” Essentially the same prohibitions apply to actions that adversely affect employees on the basis of their race, as well as to discrimination in training and apprenticeship programs.[4] In 1972, the act was extended to bar discrimination in public employment as well.[5]

Housing: Under the 1968 Fair Housing Act—which applies in the private and public sectors alike—it is illegal to “refuse to sell or rent after the making of a bona fide offer, or to refuse to negotiate for the sale or rental of, or otherwise make unavailable or deny, a dwelling to any person because of race, color, religion, sex, familial status, or national origin.”[6] Similar prohibitions apply to offering different terms and conditions to different customers, indicating racial preferences in housing advertisements, falsely claiming that units are unavailable, and discrimination in mortgage lending (buttressed by the Equal Credit Opportunity Act[7] in the 1970s). The law exempts certain transactions, however, including the sale of a single-family home without the use of an agent, provided that the homeowner doesn’t own more than three such homes at once.[8]

Higher education: Nearly all colleges in the U.S., public and private, receive federal funds. This fact triggers the central prohibition of Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act: “No person in the United States shall, on the ground of race, color, or national origin, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”[9]

Contracts: The Civil Rights Act of 1866 guaranteed that everyone would have the same right “as white citizens” to “make and enforce contracts.” Subsequent judicial rulings—solidified through changes to the statutory text, known as Section 1981—clarified that this does not merely encompass a right for willing parties to make contracts and enforce them in court. It also prohibits private actors from discriminating by race in the contracts they offer. So, for instance, a private school may not offer to contract with white parents but not black ones.[10]

These rules represent the colorblind backbone of our antidiscrimination law. In plain English, you can’t treat people differently because of their race in these areas. Few people, of any modern political persuasion, take issue with that general rule.

What has been controversial are efforts—stretching back decades—to apply the straightforward colorblind language of our nondiscrimination laws to forms of discrimination that are intended to benefit historically marginalized groups at the expense of other races (think of race-based college admissions and corporate hiring, or even the widespread racial “goals” for allocating of government contracts). To understand how these practices became common, despite clear statutory text requiring colorblindness, requires further legal history, focused on the 1970s through the 2010s.

Getting Around the Law

In general, this type of discrimination resulted from federal agencies and judges carving out exceptions to the statutory text to allow or encourage racial preferences. Sometimes, but far from always, Congress ultimately agreed, changing the text of the law to reflect the updated interpretation.

Employment

The Supreme Court’s 1979 decision in United Steelworkers v. Weber held that, despite the Civil Rights Act of 1964’s forthright ban on racial discrimination in employment (as well as legislative history making clear that Title VII’s authors did not believe that they had exempted pro-minority discrimination), the law did not necessarily ban affirmative action by private employers. The case involved a training program that reserved half its spots for black applicants, which the Court upheld as a “temporary measure” that would address a “manifest racial imbalance” in “traditionally segregated job categories” without unduly burdening white applicants.[11]

Despite this reasoning, such preferences did not fade out over time.[12] To the contrary, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC)—a federal agency that lacks regulatory authority but handles employment-discrimination allegations—wrote guidelines endorsing the private adoption of race-conscious policies, which, as of this writing, remain in effect.[13] The regulations ignore the “traditionally segregated” constraint of Weber, extracting from it and subsequent court decisions a framework that expressly allows the broader use of “goals and timetables or other appropriate employment tools which recognize the race, sex, or national origin of applicants or employees.”[14] EEOC’s lawyers summarized the process in a legal brief during the Biden administration: “Once a Title VII–covered employer concludes, through a reasonable self-assessment, that it has a reasonable basis to take affirmative action, it can then take action that is reasonable in relation to the problems disclosed by the self-analysis to address the effects of past discrimination.”[15] In a 1987 sex-discrimination case, Johnson v. Transportation Agency,[16] a majority of the Supreme Court argued that Weber should be construed to permit affirmative-action plans designed to remedy “past discrimination” regardless of whether such discrimination was the employer’s own.

Meanwhile, employers who do not discriminate by race, but instead rely on objective criteria such as written tests in hiring, can find themselves on the wrong side of the law for doing so. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 explicitly stated that it did not prohibit the use of professionally developed tests unless they were “designed, intended or used to discriminate” based on race or other forbidden criteria. But in 1971’s Griggs v. Duke Power,[17] the Supreme Court held that if different groups passed a test at different rates,[18] that could sometimes count as the test being “used to discriminate” by race under that provision, and as adversely affecting employees “because of ”[19] their race in another, even if race played no direct role in the process and there was no proof that the employer was intentionally using the test as a race proxy.

Under Griggs, if a plaintiff shows that a test or other employment practice has a disparate impact—which can be as simple as presenting different pass rates by race—then the burden shifts to the employer to show that the test is “job-related” and consistent with “business necessity,” rather than remaining with the plaintiff, as it normally would, to demonstrate a concrete problem with the exam or to prove that it is merely a pretext for discrimination. Subsequent decisions added a third prong to the burden-shifting framework, allowing challengers to win even if the employer did show business necessity, so long as the plaintiffs produced a different selection method that would serve the same purpose with less disparate impact.[20]

In theory, this standard merely requires employers to use lower-disparity hiring methods when they are equally effective and affordable. But given the reputational damage, inevitable legal costs, and risk of a judge or jury disagreeing with the employer about the appropriateness of the current hiring process or alternatives to it, the clear incentive is for employers to choose selection criteria that minimize disparities even if they are less effective.

Disparate-impact theory originally grew out of concerns about seniority systems at Southern companies where, thanks to segregation that had until recently been legal, black workers had not been able to build up experience in the best lines of work.[21] Even when it came to employment tests, many early cases involved companies that had intentionally discriminated until the law forced them to stop, had done little to measure the usefulness of the tests at issue, or were using academic-style tests without obvious relevance to the job in an era when much of the black workforce had attended underfunded and segregated schools.[22] (Griggs itself basically fit this pattern.)[23] But in a world with large racial gaps in academic performance and criminal-justice-system involvement, as well as sex differences in physical strength, it didn’t take long for the concept to smash headlong into common sense, resulting in a heavily arbitrary system where clearly sensible criteria can be rejected but employers still win most of the suits they defend.[24] Almost any selection method will have some kind of disparate impact on a protected class,[25] forcing courts to confront the difficult and subjective questions raised by the second and third steps of the framework.

By the end of the 1970s, the Supreme Court had thrown out a requirement that Alabama prison guards be at least 5’2” and 120 pounds, and yet allowed women to be outright excluded from certain roles in maximum-security prisons owing to sexual-assault fears.[26] In the same decade, an appeals court threw out a company’s categorical policy of refusing to hire those with criminal records,[27] but the Supreme Court allowed New York’s transit system to refuse to hire ex-addicts on methadone treatment without making case-by-case distinctions among applicants and job roles.[28] The evaluation of written tests came to involve fact-intensive nitpicking of exactly what skills a test measured, how thoroughly and proportionally it represented the demands of the job, and what cutoff scores or ranking systems were used—all of which must be played out in a courtroom “battle of the experts.”[29]

When a more conservative Supreme Court began to curtail this unpredictable doctrine in the late 1980s,[30] Congress wrote it into the Civil Rights Act of 1991.[31] And in 2009, the Supreme Court held that, while raw disparities are a key ingredient of legal liability, employers cannot simply throw out test results whenever a disparity emerges, because doing so may actually constitute discrimination against the higher-performing groups, further heightening legal risks.[32] In addition, while the Trump administration recently vowed to deprioritize all disparate-impact cases in its enforcement activities, private litigants still may bring such suits.[33] It is a difficult area for employers—who, after all, have to make hiring decisions somehow—in a world where race and sex disparities are the norm rather than the exception.

Lending and Housing

The 1974 Equal Credit Opportunity Act first created a carve-out in the prohibition on lending discrimination for certain credit programs that serve an “economically disadvantaged class of persons” or address “special social needs.” This has been interpreted to allow programs with explicit racial qualifications since the Federal Reserve Board first developed implementing regulations in 1977.[34] Here is an example provided in a 2021 advisory opinion from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, which handles the relevant regulations today, regarding “special purpose credit programs” administered by for-profit businesses: “[I]f a creditor establishes a special purpose credit program that requires that an applicant resides in an area that is designated as a low-to-moderate income census tract and is Black, Hispanic, or Asian, a creditor could request race or ethnicity information from applicants to confirm eligibility for the program.”[35] Paradoxically, as of this writing, the regulations stipulate that a program qualifies “only if it was established and is administered so as not to discriminate against an applicant on any prohibited basis” but also that “all program participants may be required to share one or more common characteristics (for example, race, national origin, or sex) so long as the program was not established and is not administered with the purpose of evading the requirements of the Act or this part.”[36]

Disparate-impact liability has also found its way into the Fair Housing Act over time. In a 2015 case, the Supreme Court found that Congress had “accepted and ratified” this development in 1988, when it had amended the act without explicitly repudiating disparate impact. (As noted in a dissent, while various appeals courts had endorsed disparate impact in housing by that point, Congress lacked a consensus on the issue and deliberately avoided addressing it in the amendments.)[37] The first Trump administration attempted to limit the use of disparate impact and provide additional defenses for landlords, but this effort was held up in court and ultimately undone by the Biden administration.[38]

Current housing law is similar to the Title VII rule: If a practice has a disparate impact or perpetuates de facto segregation, the landlord or public agency being sued has the burden of showing that the practice is necessary to achieve legitimate interests, at which point the challenger gets another bite at the apple to show that a different practice would be better.[39] As a result, landlords—like employers—can even be limited in their ability to consider criminal records; as a 2016 HUD guidance document summarized, blanket bans on those with records are not allowed, and even a “housing provider with a more tailored policy or practice that excludes individuals with only certain types of convictions must still prove that its policy is necessary to serve a ‘substantial, legitimate, nondiscriminatory interest.’ ”[40]

Education

The Supreme Court’s 1978’s affirmative-action decision in Bakke v. University of California openly cast aside the clear language of Title VI banning discrimination. That law, the Court contended, merely applied the Constitution’s guarantee of “equal protection” to entities receiving federal funds, despite using completely different language that is far less open to interpretation. In turn, the Court interpreted the Equal Protection Clause narrowly enough to allow affirmative action in college admissions, so long as race was considered as one factor in a holistic process with the aim of harnessing the educational benefits of diversity, as opposed to an outright quota.[41] It was a generous application of the “strict scrutiny” test usually enforced in equal-protection cases involving governmental use of racial classifications, which is allowable only if the government is pursuing a compelling interest in a narrowly tailored fashion. In the 2007 case Parents Involved v. Seattle School District No. 1, however, the Court declined to apply its higher-education precedents to K–12 districts that wanted to consider race merely to diversify their schools, keeping to a more traditional application of strict scrutiny.[42] (More recently, the Supreme Court effectively overturned Bakke and its progeny, but we shall turn to recent events later.)

Another important constitutional standard relevant in education comes from the 1977 Arlington Heights (Illinois) case,[43] which found that the Equal Protection Clause generally prohibits public entities from intentionally discriminating by race even if they do so through facially race-neutral criteria. (This is pertinent when, for example, a school changes its admissions criteria with the goal of adjusting its racial balance but does not use race in the admissions process itself.) But there is an important difference between the Arlington Heights test (intentionally selecting criteria for their racial impact) and the first step of the Griggs burden-shifting framework (using criteria that merely happen to have a disparate impact).

Government Contracting

Government contracting is yet another area where racial discrimination gradually took hold with little input from Congress. For example, a Johnson-administration executive order long required contractors to set “placement goals” if women or minorities are underrepresented.[44] Richard Nixon’s Philadelphia Plan, which was based on the order and required bidders to submit affirmative-action plans with acceptable numerical targets, was upheld by an appeals court in 1971, and the Supreme Court declined to take the case.[45]

As with disparate impact, contractor preferences were originally developed to address problems stemming from recent segregation. As the appeals court in the Philadelphia Plan case noted, Johnson’s executive order “contained findings that although overall minority group representation in the construction industry in the five-county Philadelphia area was thirty per cent, in the six trades representation was approximately one per cent. It found, moreover, that this obvious underrepresentation was due to the exclusionary practices of the unions representing the six trades.”[46] In such a case—where a disparity clearly does stem from discrimination and is not simply the result of differences in applicants’ qualifications and interest levels—temporary numerical goals can force the end of bad policies.

As my colleague Judge Glock explained in 2023, policies that favor minority contractors persisted “across all levels of government and in states and cities of every political hue.”[47] The Supreme Court’s 1995 Adarand decision, which affirmed that these instances of government racial discrimination must pass the strict-scrutiny test,[48] seemed to do little to change that.[49]

Upon taking office in 2025, Trump rescinded the executive order that undergirded the Philadelphia Plan,[50] part of a broad, concerted effort to roll back many developments of the past few years. But before proceeding to more recent history, it’s worth taking a detour to evaluate how racial bias and disparities have changed since the civil-rights era under the legal regimes described above.

Bigotry Falls; Disparities Persist

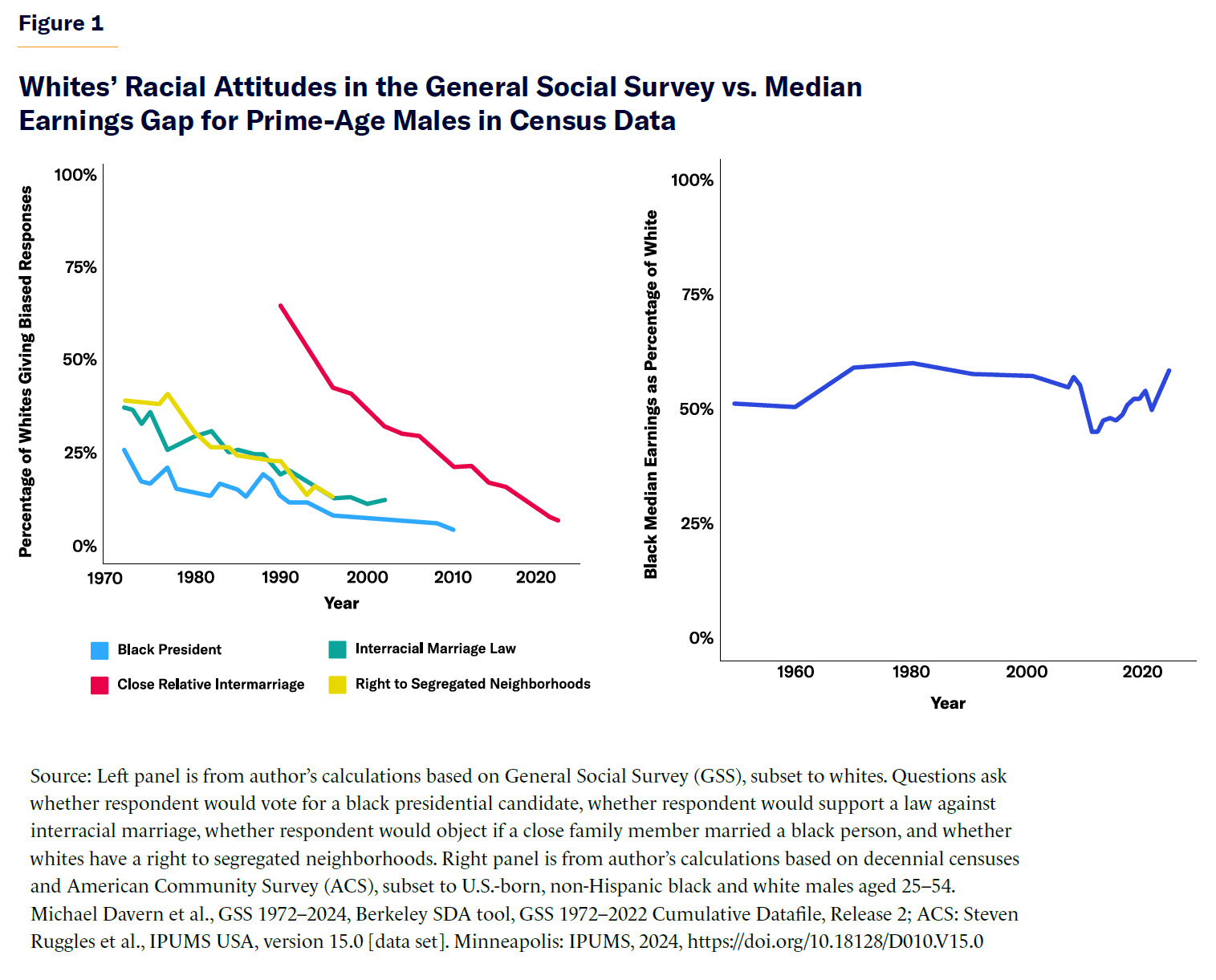

The two panels of Figure 1 provide a stark contrast. On the left are several measures of explicit prejudice measured in the General Social Survey (GSS) since the 1970s—specifically, the percentage of whites who say that they would not vote for a black presidential candidate, would support a law against interracial marriage, would object if a close family member married a black person, or believe that whites have a right to segregated neighborhoods. On the right, inspired by a study from Patrick Bayer and Kerwin Kofi Charles,[51] is a particularly drastic way of presenting the earnings gap: the median earnings for all U.S.-born black men of prime age (25–54), as a percentage of the median earnings of all prime-age U.S.-born white men—including those who do not work for any reason. This measure accounts for the fact that black men are more likely than white men to be incarcerated or unemployed, while analyses limited to workers disproportionately exclude black men at the very bottom of the socioeconomic ladder.

Over the past 60 years, democratically enacted laws have banned discrimination, formal segregation has ended, and whites have professed far more tolerant attitudes on these issues, with only a small minority holding out. Neighborhoods[52] and schools[53] have gradually become more integrated in practice as well—although, admittedly, that trend has stagnated for schools in the past few decades and remains incomplete in both spheres. Regardless, black–white economic gaps have not closed. Indeed, as Figure 1 shows, the male-earnings gap has barely narrowed over a very long period, with the median black prime-age male today bringing in a bit more than half as much money as the median white prime-age male.

How can outcomes remain so unequal? A few major theories are worth briefly exploring: 1) Ongoing gaps in human capital—including academic performance and educational attainment—coupled with structural changes in the economy that have heightened the impact of these gaps; 2) differences in family structure that worsened immensely between the 1960s and the turn of the century; and 3) continuing discrimination in practice despite the stigmatization of open racism.

This section will address the first two theories; the next section will cover ongoing discrimination. Considering all these explanations together reveals that further efforts to reduce discrimination may indeed be worthwhile but also that they can be expected to address broader racial gaps only partly.

Start with the human-capital theory. The essential point is that groups will not have equal economic outcomes if they enter the labor market with different skills and credentials, even if they encounter no discrimination based on their race from that point forward. To the extent that this theory is true, it should focus policymakers’ efforts on building human capital—e.g., by giving poorer children better access to good schools, whether through school choice or through concerted efforts to integrate schools socioeconomically.

From 1950 to 2023, in the data set employed in the right panel of Figure 1, the share of white prime-age men with a BA rose from 9% to 41%. For black men, it rose from 2% to 22%.[54] Meanwhile, the economic returns to education increased, which, all else equal, will increase gaps between racial groups with varying levels of education. Among full-time, year-round workers, college graduates outearned nongraduates by about 20% in the late 1970s but by more than 60% in the 2010s, according to an analysis from the White House Council of Economic Advisers.[55]

These crude differences in educational attainment are the result of differences in academic skills and performance, which themselves affect not only whether a student goes to college but also which colleges admit him, whether he graduates, which fields he might pursue, what jobs he may ultimately get, and how well he will perform and advance in those jobs. These gaps are pronounced during the crucial period at the end of high school: 30% of white test-takers exceed 1200 on the SAT—a benchmark for college-readiness—compared with only 8% of black test-takers, per the most recent report from the College Board. A score of 1400 is typical at the nation’s more selective colleges; 7% of whites but only 1% of blacks clear this bar.[56] Similar gaps are evident in elementary and middle school as well, and these gaps have narrowed only in fits and starts over the past 50 years,[57] as measured on the National Assessment of Educational Progress. As education researcher Sean Reardon has noted, gaps are already measurable by kindergarten and grow relatively little as children attend school, which suggests that schools are not their underlying cause (but also currently do little to ameliorate the gaps). Reardon points to poverty and ongoing de facto segregation as substantial explanations.[58]

Formally studying the links among race, cognitive skills, educational attainment, and income has proved surprisingly difficult owing to certain patterns in the data and technical limitations. For example, black Americans tend to get more education than whites with the same test scores, which complicates the interpretation when controlling for one, the other, or both of these variables. (Controlling for test scores alone often reduces the gap more than controlling for test scores and educational attainment does, for example.)[59] Many common statistical models struggle with income data, thanks to its odd skew, with nonworkers receiving zero income but a small share of the population earning extremely high amounts. However, all methods suggest that human capital is a major factor in income gaps.

One recent study on test scores and earnings growth over time concluded that “if the pre-market distributions were the same for Blacks and Whites, the racial gap in hourly earnings would be closed by 84%, with the remaining gap opening throughout life due to higher labor supply amongst White men,” though the employment gap would only be halved by matching pre-market distributions.[60] Another recent study concluded that test-score and education controls reduced the overall earnings gap by only about a third for men, but 87% for women,[61] though the author transformed the earnings data using methods that give high weight to the margin between work and nonwork.[62]

Research by Erik Hurst and coauthors has shed more light on the importance of cognitive skills. As they document, in 1960, black men were strongly sorted away from jobs that required interpersonal contact or abstract-reasoning skills. In the years since, this sorting has largely dissipated for contact jobs but hardly changed for abstract jobs. Hurst et al. show that the gap in contact jobs correlates strongly with other measures of “taste-based” discrimination; essentially, employers don’t hire blacks for contact jobs in places where people don’t want to interact with blacks. However, entry into abstract-reasoning jobs is more heavily determined by cognitive skills, where racial gaps have narrowed but hardly disappeared. Employers who hire based on these skills—or treat race as a proxy for them, which is known as “statistical” discrimination, a practice that can be economically rational but illegally deprives individuals of opportunity based directly on their race—will hire fewer blacks. Hurst et al. show how pay has increased in jobs requiring abstract skills and argue that this is a major explanation for the stagnant overall wage gap. In essence, black men’s gains in contact jobs are counterbalanced by the growing importance of abstract jobs, where gaps remain substantial.[63]

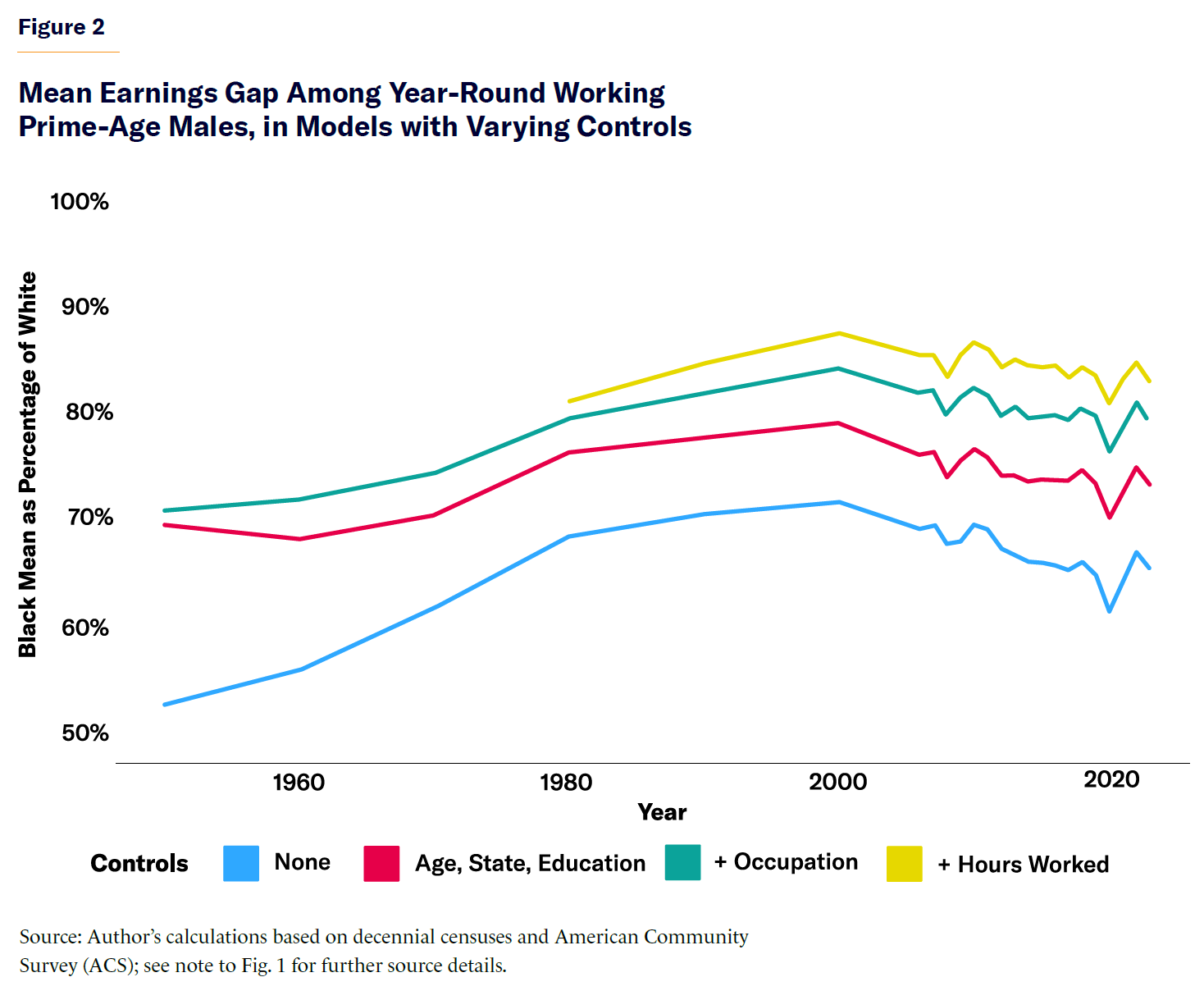

To bring some of these insights together, Figure 2 uses the same data set as the right panel of Figure 1 but takes a different approach to the analysis, focusing on apples-to-apples comparisons rather than raw disparity. It includes only those who earned money working 50 or more weeks out of the year,[64] and it calculates the mean earnings gap with statistical models rather than simply plotting the difference in medians. Four models are run separately on each year of data. Model 1 has no controls. Model 2 controls for age, state of residence, and education level. Model 3 additionally controls for broad occupational groupings. And Model 4 further controls for usual hours worked, although this variable is not available until 1980.[65]

This approach reveals powerful mechanisms behind the earnings gap. Some of these are mechanisms by which discrimination might operate—as an example, the occupation control in 1950 captures the formal segregation of job lines. But others clearly measure human-capital issues, such as education levels in the late 20th and early 21st century, when most men of all racial groups had high school diplomas and universities practiced race-based admissions. In recent years, the analysis also leaves an unexplained gap in the ballpark of 15%, which reflects factors not measured in the underlying data set, including discrimination, as well as cognitive and noncognitive skills that increase pay within occupations. This leftover gap varies in similar analyses depending on the data set employed, the choice of outcome variable (such as total earnings vs. hourly wages), and the controls used.[66]

The male earnings gap serves as an excellent case study in the persistence of inequality, but it is worth drawing attention to measures that show the power of family structure as well. As of 2022, nearly 70% of black women giving birth, but less than 30% of white women, were unmarried.[67] In 1965, those numbers were 24% and 3%, respectively.[68]

Being raised by a single parent can have immediate and obvious effects on well-being: two adults tend to earn more money than one. As sociologist John Iceland showed in a 2019 paper, these differences in family structure can explain a significant amount of the racial gaps in poverty rates.[69] Unlike individual wages, poverty status depends on such factors as how many children a family must feed and whether one or two incomes support the household. In Iceland’s statistical decomposition, about two-thirds of the poverty gap between whites and blacks could be explained by basic demographic differences as of 2015, while only half the larger 1959 gap could be explained this way. Family structure by itself explained about a third of the 2015 gap.

Research has revealed how family structure, particularly father absence, has longer-term negative impacts on children, on outcomes ranging from educational performance to criminal offending. There are important scientific difficulties in proving causation in such situations, but studies using more elaborate methods (such as relying on birth order or “natural experiments” caused by policy changes) often continue to find bad effects.[70] Family structure may help explain why racial gaps appear smaller for women than for men: some research suggests that family structure has a larger impact on male children,[71] and black women’s lower rate of married motherhood is likely one reason[72] they have long had higher labor-force participation than white women.[73]

It is abundantly clear that today’s racial gaps are not just about ongoing discrimination. Human capital and family structure have become increasingly powerful explanations for these gaps over time. This should temper our expectations for antidiscrimination law. But none of this proves that such discrimination is negligible, or that antidiscrimination law shouldn’t be part of an effort to provide equal opportunity and protection to all Americans. So let us review some evidence directly pertaining to that issue.

Audit Studies

At least in some situations, it is possible to measure the extent of discrimination with scientific rigor by simply running an experiment. In an audit study, researchers send “testers” of different races to seek housing or to apply for jobs in the real world, but with fake applications designed to ensure that the only difference between the candidates is race itself. The testers are matched in pairs that apply to the same places; the researchers then measure whether testers of one race or another systematically receive more callbacks or offers. More economically, one might do a “correspondence” study without face-to-face contact, though, in this case, the testers’ races must be implied by their names. Many of these studies have been done over the past half-century, and their results have much to teach us.

A 2015 report from the Department of Housing and Urban Development compiles the results of housing audit studies and shows that several types of discrimination waned massively between 1977 and 2012. In the 2012 study, black applicants were rarely told, incorrectly, that units weren’t available, which had previously been common. Furthermore, white applicants were only slightly more likely to be shown more rental units in total. However, the difference in likelihood of being shown more units has remained steadier in the sales, as opposed to the rental, market (where the white tester in a given pair was 9 percentage points more likely to be the one shown more units).[74]

The one type of discrimination that increased was “steering” applicants to neighborhoods in which their race is more prevalent. As of 2012, white testers were 8 points more likely to be recommended or shown units in whiter neighborhoods. This type of discrimination is illegal and can slow integration, though it can also reflect the typical consumer’s preferences. In surveys, for example, both whites and blacks report wanting to live in diverse neighborhoods rather than segregated ones—but they seem to mean different things by that, with blacks wanting to live in neighborhoods about half-black on average and whites preferring neighborhoods where blacks are closer to their national population share of 13%.[75] Given these preferences, it’s not hard to imagine how a real-estate professional might get in the habit of treating, say, a majority-black neighborhood as a likelier option for black customers than for white ones, though it is worth stressing again that this violates the law, regardless of the motivation.[76]

Meanwhile, in employment discrimination, several studies—and their limitations—are worth discussing. The first is a meta-analysis of previous works by Lincoln Quillian and several coauthors, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in 2017. “Since 1989,” the study found, “whites receive on average 36% more callbacks than African Americans, and 24% more callbacks than Latinos. We observe no change in the level of hiring discrimination against African Americans over the past 25 years, although we find modest evidence of a decline in discrimination against Latinos.”[77]

A notable criticism of this body of research was presented in a study by Shawn Bushway and Justin Pickett,[78] who noted the appearance of a significant publication bias in this literature, in which studies finding discrimination are published but others are discarded. (This is detectable statistically, essentially by checking whether studies with lower sample sizes have results that are distributed symmetrically around results of studies with big samples, which estimate effects more precisely—or whether studies with undesirable results appear to be “missing.”) Bushway and Pickett pointed out that studies focusing on men or lower-educated applicants tended to find the biggest effects; they highlighted a particularly large and rigorous study with more modest findings, to which we now turn.

Patrick Kline and two coauthors sent 83,000 fake applications to jobs across the country offered by 108 major employers and checked to see which received responses. The authors detailed overall results in a 2022 paper,[79] and the contact gaps for 97 specific firms—identified by name—in a subsequent working paper.[80] Twenty-one companies contacted slightly more black applicants, though these differences were small enough to have plausibly occurred by chance. The authors could say with statistical confidence, meanwhile, that 23 companies discriminated against black applicants.

With all the data grouped together, about 25% of white applicants were contacted within 30 days, versus 23% of blacks. There are several ways to interpret this overall disparity. Out of every 100 contact attempts by black applicants, there were only about two that went unanswered but would have been answered from a white applicant. However, given that three-quarters of applications go unanswered for everyone, this amounts to a roughly 10% gap in successful attempts. On top of that, if companies discriminate at this initial stage of the process, they likely discriminate also at other stages (as some other research shows).[81] Even a small level of discrimination will add up across multiple points in the consideration of each application and over and over again as a given individual applies to numerous companies and positions over the course of his life.

A major limitation of this study is its focus on large employers, as well as on low- to moderate-skill workers. The fake applicants were split 50/50 as to whether they claimed an associate’s degree or only a high school diploma; in the 2022 ACS, these categories cover roughly the 5th to the 55th percentiles of education for prime-age, U.S.-born Americans.[82]

Because it was a correspondence study, it relied on names to signal race. Other research compellingly shows that, in addition to race, names signal social class. Indeed, different stereotypically “black names” send different class signals, implying that the results of these studies will be sensitive to the precise mix of names chosen.[83] Notably, though, in one study investigating these effects, survey respondents were asked why they thought that a given black name signaled a certain social class, and a third of the time, they admitted that it was just an assumption based on the name’s racial connotations.[84] As Kline et al. explained, the particular names used in their audit did not appear to generate different responses from employers aside from the effect of the race and sex they signaled.

In general, the limitations of this study and others are worth remembering, but the experimental design nonetheless makes this line of research a compelling demonstration that some measure of antiblack discrimination likely persists, even if it cannot fully explain the persistence of racial gaps. And rigorous audits like Kline’s could prove a potent weapon in the fight against discrimination.

With trends in bias and disparity in mind, let’s proceed to more recent legal developments.

A Changing Legal Landscape for “Reverse Discrimination”

Since the heyday of left-wing judicial activism, the Supreme Court has gradually shifted rightward: at first, in the hands of moderate swing-voting justices such as Sandra Day O’Connor and Anthony Kennedy, and now, firmly under the control of a 6–3 Republican-appointed majority whose members—despite numerous differences among themselves—share some commitment to originalism and textualism. These past few years, lawsuits challenging DEI practices have become so common that the Advancing DEI Initiative of New York University’s Meltzer Center has created a special website to track them.[85] Efforts to undo the changes outlined in the previous section have met with mixed success.

At the outset, it is worth drawing a distinction between constitutional precedents and statutory precedents. Several of the majority justices, particularly John Roberts and Brett Kavanaugh,[86] are far more hesitant to overturn incorrect precedents when they involve the interpretation of statutes. The logic is that if Congress believes that the Court has misinterpreted a mere statute, Congress can simply clarify the relevant text; amending the Constitution, by contrast, is a far more daunting process. In this view, congressional inaction thus implies some form of agreement with incorrect court rulings and agitates against overturning them. Under 1984’s Chevron decision,[87] courts also granted considerable deference to executive-branch agencies’ interpretations of statutes within their field of expertise, though the Supreme Court ended this practice with 2024’s Loper Bright.[88]

The biggest change by far, in this area of law, has been Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard (SFFA),[89] in which the Court reconsidered Bakke and the line of affirmative-action cases that followed. The majority decided that the Equal Protection Clause did not allow public colleges broad leeway to discriminate for the purpose of increasing diversity. In effect, it threw out the special rules it had developed for higher education and applied the typical “strict scrutiny” analysis used in other areas when the government considers race. And since, under Bakke, Title VI of the Civil Rights Act merely applies the Equal Protection Clause to all entities receiving federal funds, the Court’s new analysis automatically applied to most private schools, including Harvard, without the need to reinterpret the statute itself (and thus alienate the justices who hesitate to do such things).[90] Early signs indicate mixed compliance: at some elite colleges, the first class that was admitted after the ruling revealed the kind of substantial demographic changes that one might have expected; at others, there was virtually no change; at still others, demographic changes suggested a doubling-down on racial preferences.[91]

Other attempts to stop government entities from openly discriminating by race, though somewhat lower-profile, have also been successful. District courts, for example, overturned the laws instructing the Small Business Administration[92] and Minority Business Development Agency[93] to presume that members of specific racial groups were disadvantaged and thus eligible for benefits, as violations of the Equal Protection Clause. (The former law, the Small Business Act, has identified racial groups by name since 1978, though this preference was first made explicit by the executive branch.[94] The latter agency has its roots in a Nixon-administration executive order but did not formally receive its problematic statutory authorization until 2021.)[95] Other challenges have succeeded against a pandemic-era program targeting debt relief to black farmers—though this was replaced by a thinly veiled program to send money to farmers alleging that they have faced discrimination[96]—as well as grants for minority-owned restaurants.[97]

Another set of lawsuits deal with changes in admissions criteria at selective high schools—most prominently, Thomas Jefferson High School in Northern Virginia,[98] New York City’s “specialized high schools,”[99] and Boston’s “exam schools.”[100] These are public schools and thus state actors—but in these cases, the state has pursued racial ends through carefully selected, facially race-neutral proxies. In all cases, while the admissions processes didn’t consider race directly, officials left a clear public record showing that they adjusted those processes to calibrate the racial balance of enrollment. (Asians and whites tend to be overrepresented at selective high schools while blacks and Hispanics are underrepresented.) Under Arlington Heights, recall, the Equal Protection Clause generally bars government entities from intentionally using proxy criteria to discriminate by race. The challenges involving Thomas Jefferson and Boston failed in the circuit courts and the Supreme Court declined to review them, while, as of this writing, the students suing New York have won an important victory in the Second Circuit regarding the relevant legal thresholds.

Interestingly, in the New York case, the district’s initiative failed, and Asian presence at the most selective schools actually rose. Nonetheless, the court held that it was legally sufficient if some individual Asian students didn’t get in who would have otherwise, even if more Asians in total were admitted. This was in marked contrast to the other two decisions—where the changes to admissions processes did have the intended effect, but courts still decided there wasn’t a disparate impact because Asians remained overrepresented at the schools. On this view, it is legal for a public school district to intentionally make Asians worse off as long as Asians continue to outperform other groups—the Handicapper General’s Equal Protection Clause.

Thus far, the shift has been less pronounced in employment and private-contract law, where disputes are handled under statutes and the new Supreme Court has not yet gotten involved. In one notable exception, a challenge to the Fearless Fund—which offered grants exclusively to black female entrepreneurs—resulted in a settlement[101] after the Eleventh Circuit granted a preliminary injunction.[102] In finding that the lawsuit was likely to succeed, the court noted that the fund’s grant agreement was a contract with obligations on both sides (making Section 1981 applicable) and that, while Weber and subsequent cases allow race-based decisions within certain parameters, they do not allow the use of race as an “absolute bar.” This is obviously a promising route to challenging explicit discrimination, though recurring legal issues are likely to include what counts as a “contract” (as opposed to, e.g., a gift) and who has standing to sue (including organizations representing anonymous victims).[103]

The first several months of the second Trump administration have seen the executive branch join this fight. Through executive orders, for example, the president has vowed the end of DEI in the federal workforce, directed agencies to investigate such practices elsewhere,[104] announced a belief that the disparate-impact doctrine is unconstitutional (and thus to be deprioritized in federal enforcement efforts across all areas of the law), and instructed agencies to begin the process of rewriting problematic regulations.[105] It has also reshaped the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division, not only through political appointees but also by clearing out or reassigning career staff,[106] and is seeking to eliminate a 1981 consent decree, stemming from a disparate-impact case, that impedes the use of civil-service exams in federal hiring.[107]

Fearing legal repercussions, many universities[108] and private employers[109] have scrambled to bring their policies in line with the text of the nation’s antidiscrimination laws. The coming months and years will no doubt see deeper regulatory changes and legal challenges to them, though a future administration could reverse these decisions.

Equal Protection Against Discrimination

Antidiscrimination law has always been subject to debate—from the discussions in Congress that resulted in the Civil Rights Act of 1964, through the 1990s-era fights over race-based decision-making, to today’s lively discussions about DEI and “wokeness.” These debates have produced several competing visions for antidiscrimination law.

A dedication to freedom of association, for example, motivated Barry Goldwater’s 1960s opposition to antidiscrimination laws and has reappeared in numerous books over the years, including Richard Epstein’s Forbidden Grounds: The Case Against Employment Discrimination Laws[110] in 1992 and Christopher Caldwell’s The Age of Entitlement in 2020.[111] For the time being, it seems safe to say that legalizing private discrimination, regardless of the target, remains well outside the Overton Window.[112] Notably, discrimination against minority groups is best documented at the lower end of the job market, where audit studies tend to focus, while open preferences for those groups have been most common at elite colleges and top corporations; in a world of fully legal discrimination, this rather unfair pattern would likely intensify.

Much more politically realistic, almost by definition, is the status quo as of just a few years ago: a system where the law prohibits discrimination, and yet generous exceptions and carve-outs are available to those wishing to prefer underrepresented minorities. It is worth reiterating that this balance was achieved mostly through executive agencies and judges twisting the law to allow it. Americans in general continue to oppose racial preferences, with even black Americans specifically opposing them in many surveys. In the 2022 GSS, 70% of Americans, and just over half of black Americans, said that they opposed preferences for blacks in hiring and promotion.[113] Similarly, Gallup’s polling on the SFFA decision found 68% support for the decision among whites and 52% support among blacks.[114]

A backlash against double standards is a natural reaction. And racial favoritism raises additional issues as the nation diversifies and the horrors of past decades recede. It’s one thing to grant preferences or special protections to black workers who attended segregated schools as children; it’s another to grant preferences to Hispanics over Asians for the foreseeable future, merely because the latter tend to perform better academically and economically. So while an identitarian,“equity”-seeking approach has certainly shown itself to be a political possibility, it has proved neither popular nor desirable as an actual solution to the country’s racial problems.

The last major option, of course, is colorblindness—the idea that, at least as far as government and business are concerned, we should treat people as individuals without regard to their race. This idea has an impressive history, appearing in the texts of our 19th-century refounding, prominent Supreme Court decisions, and the rhetoric of civil-rights leaders, as Coleman Hughes details in The End of Race Politics.[115] Colorblindness polls well among the general public today. It offers the intuitively appealing promise of a single set of rules that protect everyone, giving all a stake in enforcement and respecting the Constitution’s equal-protection guarantee. It comports with the actual text of our key antidiscrimination laws. And beyond the scope of antidiscrimination law, it certainly doesn’t prevent us from fixing deeper problems that hinder opportunity and affect some groups more than others—such as bad schools and impoverished neighborhoods.

So if pure libertarianism isn’t a serious option and DEI isn’t working, how might a colorblindness agenda for antidiscrimination law look?

The Executive and Judicial Branches

A new law requires the agreement of both houses of Congress and a president. With executive actions and court rulings, by contrast, only one body, or even just one person, can make the decision. So let’s begin there.

The executive branch can enact important reforms on its own, a process that Trump has already set in motion, as noted above, with new developments coming rapidly. As the administration rewrites regulations, remakes the federal bureaucracy, and fights race-conscious DEI policies throughout the country, however, it should also continue to aggressively pursue more traditional intentional-discrimination cases, driving home the point that fair, evenhanded enforcement is the goal. Supporters of Trump’s reforms should also bear in mind that what one presidential administration can change through the executive branch, the next can change back.

Meanwhile, given the current makeup of the Supreme Court, constitutional challenges against race-conscious practices are likely to see continued success via the strict-scrutiny test. For litigants, government entities and federal-funds recipients that openly discriminate are the most obvious targets; entities that intentionally manipulate selection criteria to benefit favored races are also vulnerable. Resolving the circuit split involving school districts that deliberately manipulated selective high schools’ demographics in favor of colorblind rules should be a high priority.

Rolling back disparate impact in employment law, or statutory precedents that allow some forms of affirmative action in the private sector, will be somewhat more difficult. Where the Supreme Court lacks the votes to overturn precedents, the judicial branch should look skeptically at disparate-impact justifications and rigorously enforce the limits on private-sector affirmative action, including by narrowly interpreting older decisions made in contexts where overt discrimination had recently been common and legal.

Two somewhat long-shot paths to ending disparate impact have generated discussion. One is noted in Antonin Scalia’s concurrence in the Ricci case and is now the position of the Trump administration: disparate-impact doctrine itself may be unconstitutional, as, in Scalia’s words, it requires “employers to evaluate the racial outcomes of their policies, and to make decisions based on (because of) those racial outcomes.”[116] On that logic, the Supreme Court could strike down the statute that now endorses the doctrine. It may be something of a stretch, however, to insist that Congress lacks the authority to prod businesses to choose lower-disparity hiring methods when such methods are available and equally effective—which, on its face, is all the doctrine does, despite its many dysfunctions in practice. Those dysfunctions may be best addressed through the political process rather than by constitutionalizing the issue.

The other possibility, noted in Richard Hanania’s The Origins of Woke,[117] involves a careful and sure-to-be-contentious parsing of the statute. The “Purposes” section of the 1991 Civil Rights Act said that a goal of the law was to “confirm statutory authority and provide statutory guidelines for the adjudication of disparate impact suits under title VII”—but this section does not have the force of law. The operational language instead declares that an “unlawful employment practice based on disparate impact is established under this title only if” various criteria are met (essentially the rules the Supreme Court had developed starting with Griggs); but it does not alter the section of the statute that defines and prohibits discrimination. Courts could simply decide that this language does not require the use of the disparate-impact doctrine at all, allowing them to overturn Griggs or substantially limit the doctrine’s scope.

I’ll close this section with a long shot of my own.[118] A turbocharged reluctance to overturn bad statutory precedents is misguided, and the justices most strictly adhering to it should reconsider. Yes, it is easier to amend a statute than it is to amend the Constitution, and that consideration, combined with others, such as the general value of stability in law, might reasonably tip the balance toward stare decisis in a close case. But is it easy enough to change a statute that the highest court in the land should simply refuse to correct serious legal mistakes, on the assumption that Congress’s failure to do so constitutes an endorsement of a prior ruling? In reality, changing a statute requires a majority in the House, at least a majority in the Senate (and typically a three-fifths supermajority to overcome a filibuster), and the signature of the president, excepting rare occasions when extra-large majorities in Congress might override a veto. It also requires the issue to be high enough of a priority to be worth the effort and distraction from other matters. Given these limitations, Congress might deliberately write a law to say A instead of B and yet might also lack the votes to change it back to A if the Supreme Court mistakenly says it means B[119]—and this situation may persist for years.

A greater willingness to overturn statutory precedents would enable much stronger enforcement of private-sector antidiscrimination law as originally written, which, as we have seen, is decidedly colorblind. Absent such a move, it might prove difficult to truly uproot such efforts.

A Grand Bargain for Congress?

The ideal approach for antidiscrimination law would be to ban discrimination against Americans of all races, encourage the use of objective, transparent hiring processes, and fund vigorous enforcement. Today, it is challenging to pass a law on a controversial topic without the use of the reconciliation process (which would not apply to most changes in discrimination law), but here is how a compromise might look.

The colorblind statutes outlined at the beginning of this report should remain, with language reiterating their original meaning as needed to dispense with wrongly decided court precedents, while any statutes that explicitly or implicitly facilitate discrimination (such as by targeting carve-outs to “disadvantaged classes”) should go. Judge Glock has proposed model legislation that would achieve this for government contracting, for example.[120]

The disparate-impact doctrine that began with Griggs should be limited or eliminated. At minimum, obviously legitimate criteria (such as physical tests for public-safety workers, or criminal-record checks for tenants) should be generally exempted from challenge if used in good faith, and employers using other tests or criteria should be able to submit their supporting documentation for approval by EEOC rather than waiting to get sued. More ideally, disparate-impact claims should be limited to the intentional-discrimination context, such as when there is evidence that an employer deliberately chose a selection method for its racial impact or when disparate-impact statistics are part of a broader case alleging intentional discrimination.

Those would be painful concessions for the left, even if they are broadly in line with public opinion. So here is what a compromise might demand of the right: the government could fund ongoing audit studies (specifically designed to avoid the major pitfalls described above) to identify which employers and landlords might be truly discriminating, i.e., treating otherwise identical candidates differently based on their race. It should work with companies to rectify any problems and sue if necessary. It should also encourage companies to audit and reform their own processes, including for internal promotions (which are far harder to evaluate from outside a company, absent a specific allegation of discrimination), so long as such audits narrowly target illegal disparate treatment.

Conservatives should also consider injecting a smidge of libertarianism into their views on affirmative action. It is unjust for a government-run college, a nonprofit that receives copious taxpayer funding, or even a sizable private business to withhold opportunities on the basis of race. But is that true of small, genuinely private nonprofits, operating independently? Might they properly deserve some leeway to offer training, grant, and scholarship programs to members of particular groups? Conceivably, giving up some carefully delineated ground on these kinds of programs might help grease the wheels of compromise—and it would be consistent with conservatives’ general reluctance regarding government interference in the private sector.

The left needs to give up its toxic obsession with racial bean-counting and its assault on merit-based hiring. The right needs to admit that straightforward discrimination, in which otherwise similar applicants to jobs and housing opportunities are treated differently due to their race, is still present in modern America, if rarer than it once was. At the nexus of the two could lie a compromise for colorblindness.

Conclusion

The rise of “wokeness,” the backlash against it, the Trump administration’s war on DEI, and a new majority on the Supreme Court present America an opportunity to renegotiate the compromises that have governed racial discrimination since the Civil Rights Act of 1964. A genuine dedication to colorblindness is easily the most attractive option. America should finish the job of stamping out antiblack discrimination while ending the double standards that have long made antiwhite (and, more recently, anti-Asian) discrimination effectively legal. Those of all races could unify around a fair system with protections for all—and turn their focus to the deeper matters that hold too many back from the opportunities that the American dream has to offer.

Endnotes

Photo: ericsphotography / E+ via Getty Images

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).