Fueling The Conversation, Week of July 28th, 2025

Last week, I praised EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin for taking on the important and necessary work of right-sizing the federal regulatory state. His reorientation of the agency towards pursuing environmental quality without crippling the economy is a welcome return to the original mission of the EPA. But while I stand by this praise, it’s also important to hold the EPA accountable when it veers off course, as is the case with the newly proposed Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS).

Originally included in the Energy Policy Act of 2005 and expanded in the Energy Security and Independence Act of 2007, the RFS mandates that the EPA set a minimum level of biofuel that must be mixed into transportation fuel. This act was passed amid President George W. Bush’s insistence that we break our “addiction” to foreign oil, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and lower energy costs. For those who are keeping score, the program has struck out on all three. And yet, the EPA is doubling down on the program with its latest proposal.

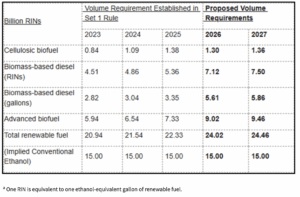

In June, the EPA submitted its proposed RFS for 2026 and 2027, enacting the highest volume requirements ever: 24.02 billion gallons of total renewable fuel in 2026 and 24.46 billion in 2027, compared to 20.94, 21.54, and 22.33 for 2023-2025. An additional component of the new rule is the differentiation between domestic and foreign biofuels, with the EPA assigning a 50% Renewable Identification Number (RIN) value to foreign equivalents while granting domestic gallons the full credit. I’ll talk more about the problems with RINs in next week’s column.

The justification behind the EPA’s increased requirements sounds appealing. The agency claims that the rule “ensures the RFS program remains true to Congress’ original intent of increasing the use of homegrown American biofuels, unleashing American energy, and supporting rural economies,” declaring that its proposal “strengthens U.S. energy security by reducing reliance on foreign sources of oil by roughly 150,000 barrels of oil per day over the time frame of the Set 2 rule, 2026 and 2027.”

Supporting American agriculture and energy independence are commendable goals, but the RFS is a poor way to achieve both. By forcing refiners to mix in more biofuels than the market calls for, the RFS raises energy prices due to both the lower energy content of ethanol and the high compliance costs fuel companies face under complex regulations. Purchasing RINs also adds to operational expenses. In 2019, the Congressional Budget Office reported that increasing the required use of corn-based ethanol raised motor fuel prices outside the Midwest — by eight cents per gallon in Hawaii, two cents in Oregon, and six cents in Washington — primarily due to the added costs of transportation and storage infrastructure. As for the goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions, research has shown that ethanol use has not resulted in a net reduction in lifecycle emissions.

Biofuel also poses a problem for certain engines. Because ethanol attracts and holds moisture, water can accumulate in the fuel tank and cause erosion. Exposure to oxygen can also result in corrosive byproducts that harm engines over time, raising costs for owners as they’ll have to spend more on repairs and preventive measures, all thanks to the RFS. That’s why boaters, classic car enthusiasts, motorcyclists, and lawn care professionals will go out of their way to find ethanol-free gas pumps.

As for the idea that we need biofuel to wean us off oil, it makes even less sense after the shale revolution. According to IER’s 2024 North American Energy Inventory, oil production in the U.S. has increased by 149% since 2005. We also have 1,657.5 billion barrels of technically recoverable oil and 44.4 billion barrels of proved oil reserves. If the goal of the RFS was to reduce our dependence on foreign oil, then mission accomplished. Given our vast oil resources, the EPA should reduce the volume requirements, not increase them to their highest levels.

The EPA would better serve the American people by modifying its RFS regulation to give refineries the flexibility to determine the amount of biofuel to include in transportation fuel based on need and not mandate specific volumes. The Trump administration made that type of decision in the case of automobiles by ending the Biden administration’s electric vehicle mandates. Why not do the same here?

At IER, we are committed to calling balls and strikes, which means we stand for the nonpartisan principles of free markets and consumer choice while fending off efforts from special interests to increase the utilization of their preferred energy sources through the political system.

We know that the biofuel industry is a formidable political machine that plays up the narrative that this program is necessary to help American farmers. The EPA shouldn’t give in to their pleas. It runs contrary to their goals of pursuing American energy dominance, reducing unnecessary regulatory burdens, and lowering energy costs for American families. Unfortunately, in this case, the EPA is striking out.

__________________

Fueling the Conversation, a weekly column by IER President Tom Pyle, offers a principled take on energy events. Energy underpins all aspects of modern life, so policies that artificially limit production hurt everyday people paying to heat their homes and drive to work. “Green” groups push these policies for ideological reasons, but this column uses economic logic and hard facts to advocate for energy freedom.